Locking Lumbar Interbody Cementation for Degenerative Scoliosis by Mini-Open or Percutaneous Approach

by Kung Chia Li1*, Ching-Hsiang Hsieh1, Ting-Hua Liao1, Shang-Chih Lin2, Yu-Kun Xu3

1Yang Ming Hospital, Chiayi 60054, Taiwan

2Graduate Institute of Biomedical Engineering, National Taiwan University of Science and Technology, Taipei, Taiwan

3Graduate Institute of Applied Science and Technology, National Taiwan University of Science and Technology, Taipei, Taiwan

*Corresponding author: Kung-Chia Li, Yang Ming Hospital, Chiayi 60045, Taiwan.

Received Date: 21 September 2024

Accepted Date: 26 September 2024

Published Date: 28 September 2024

Citation: Li KC, Hsieh CH, Liao TH, Lin SC, Xu YK (2024) Locking Lumbar Interbody Cementation for Degenerative Scoliosis by Mini-Open or Percutaneous Approach. J Surg 9: 11147 https://doi.org/10.29011/2575-9760.11147

Abstract

Purpose To report the results of locking lumbar interbody cementation (IBC) for the treatment of symptomatic Degenerative Lumbar Scoliosis (DLS).

Methods Between Jan 2013 and Dec 2018, 62 patients with DLS received mini-open IBC under general anesthesia (OIBC) with 67.3±8.1 years and 98±10 month follow-up. Between 2019 and 2022, 32 DLS patients received percutaneous IBC under local anesthesia (PIBC) with 73.2 ± 8.0 years and 48±6 month follow-up. Patients with flexible DLS and fragile medical conditions were assigned to or percutaneous IBC under local anesthesia (PIBC). The clinical and radiological results and complications were retrospectively analyzed.

Results The operative time of OIBC vs. The PIBC was 121 ± 26 vs. 80 ± 16 min, with an estimated blood loss of 196 ± 68 min. 18.0 ± 2 ml. Preoperative VAS and ODI were 7.9 ± 0.7 and 72.8 ± 8.7 vs. 7.7 ± 0.8 and 71.9 ± 8.6, respectively. At the final visit, VAS and ODI were 2.8 ± 1.1 and 24.3 ± 9.3 vs. 2.7 ± 1.2 and 24.7 ± 8.5. Preoperative Cobb’s angles were 40.1° ± 14.6° vs. 18.8° ± 7.8° and 8.5° ± 7.4° vs. 3.7° ± 3.5° at the 24h follow-up and 14.6° ± 9.4° vs. 6.2° ± 4.4° at the final visit. Lumbar lordosis was corrected significantly in both groups. Asymptomatic cement leakage was common in 21 OIBC and 15 PIBC cases. 4 OIBC and 1 PIBC patients suffered minor perioperative complications. Two OIBC and one PIBC patients had symptomatic cement leakage and required revision surgery.

Conclusions Both OIBC and PIBC showed significant improvements in clinical and radiological parameters. PIBC was good for polymorbid patients.

Keywords: Cement Discoplasty; Degenerative Lumbar Scoliosis; Interbody Cementation; Percutaneous Interbody Cementation

Introduction

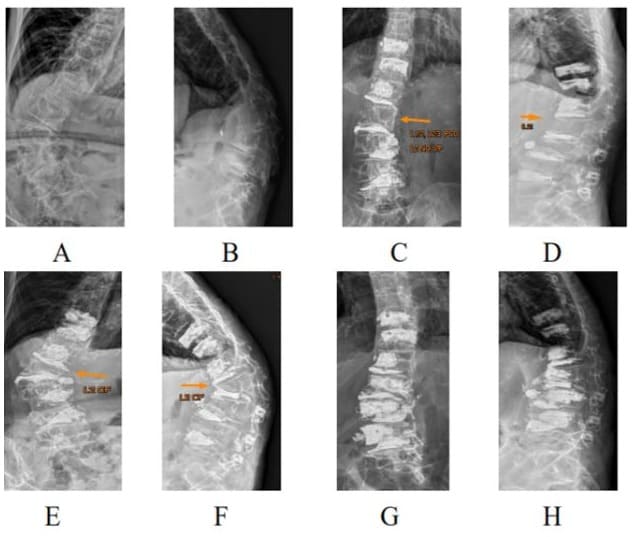

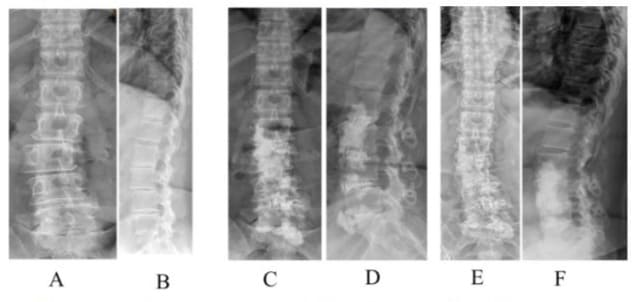

Degenerative Lumbar Scoliosis (DLS) may cause low back pain, leg pain, coronal imbalance and disability [1,2] and sometimes, surgery, including spinal decompression or fusion, is recommended. However, posterior instrumentation with bone grafts for the treatment of DLS is not only time consuming, but also has an elevated risk of complications [3,4]. The high incidence of operation complications leading to an advancement as an alternative treatment has launched in the past decade, i.e., Percutaneous Cement Discoplasty (PCD). This procedure was intended to decrease spinal instability for the advanced disc degeneration and promise clinical results with low complication rates have been reported [5-10]. PCD has been reported as an excellent target therapy for pain relief, but comparatively poor for spinal stenosis and scoliosis correction. PCD has no significant correction for lumbar lordosis or scoliosis and 14.7% of 156 PCD patients required second decompression surgery [5]. Due to osteoporosis in PCD elders, adjacent vertebral fractures may occur when scoliosis was corrected and increased stress in the vertebral bodies on the concave side (Figure 1).

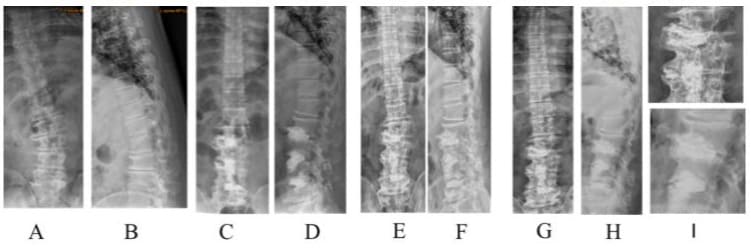

Figure 1: A 68-year-old 32-kg female with degenerative scoliosis 70‘, thoracolumbar kyphosis 83’ (A, B) was treated with L3/5 open interbody cementation and L1/2, L2/3 cement discoplasties (C, D). An L2 compression fracture occurred one month later and caused re-kyphoscoliosis (E, F). L2 was reconstructed with one body cage with cementation and L3, L4 prophylactive vertebroplasties were done (G, H).

To prevent the high complication rate of posterior instrumentation in traditional fusion surgery and increase the correction rate of scoliosis and lordosis in PCD, locking lumbar Interbody Cementation (IBC) was developed. Initially, the mini-open farlateral approach of IBC (OIBC) is used to treat elderly patients with both back and leg pain, mainly due to DLS. [11] The long-term radiological and clinical results of OIBC were reported similar to those of traditional instrumentation fusion with fewer operative parameters and complications. However, general anesthesia is required for OIBC, which is not allowed in some elderly patients. A further step, percutaneous interbody cementation under local anesthesia (PIBC), was developed to solve the elderly issue. The specific aim of this study was to retrospectively study the mid-term radiological and clinical outcomes of PIBC.

Materials and Methods

Patient Population and Data Collection

Between Jan 2013 and Dec 2018, 62 patients with low back and leg pain and advanced DLS received mini-open IBC with cages under general anesthesia (OIBC) with 67.3±8.1 years and 98±10-month follow-up. Between 2019 and 2022, 32 DLS patients received percutaneous IBC, without cages of course, under local anesthesia (PIBC) with 73.2 ± 8.0 years and 48±6-month follow-up. Patients with flexible DLS and fragile medical conditions were treated with percutaneous IBC under local anesthesia (PIBC). The clinical and radiological results and complications of these two groups were retrospectively analyzed. The inclusion criteria were as follows: patients with moderate-to-severe low back and leg pain (Visual Analog Scale [VAS] score of 6 or more), who did not respond to conservative treatment after a minimum of 6 months, with DLS, and moderate-to-severe lumbar stenosis based on Schizas classification [12]. Patients with active infections or oncological conditions were excluded. Patients with BMI greater than 30 were excluded from this study due to technique problems. Finally, total of 94 patients were included with mean BMI of 22.6 ± 2.7 and male to female ratio of 15:79.

Preoperative Radiological Studies

Before the indication for surgery, all cases using conventional X-rays, CT scans, and magnetic resonance imaging were integrated for the study. Radiological studies were performed both in the standing position (anterior-posterior and lateral views) and in the supine and decubitus positions (anterior-posterior and lateral views). CT of the thoracolumbar and lumbar spine was routinely performed. Magnetic resonance imaging was used to analyze the level and severity of spinal stenosis.

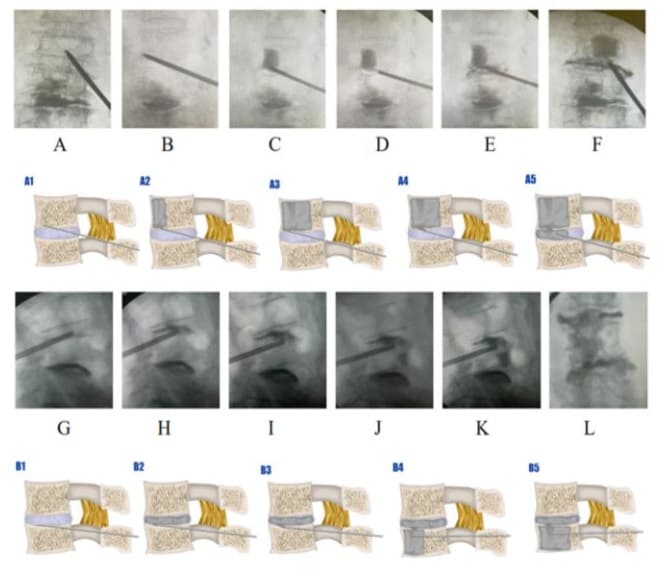

Operating Technique

The detailed procedure of OBIC has been described in a previous article [11]. The stepwise procedure of PIBC is presented and interpreted in Figure 2. All the patients initially underwent manual reduction. Patients were first changed from supine to prone position, and C-arm fluoroscopy was used to locate the scoliosis site and monitor cementation. Six members cooperated to do manual reduction. One anesthesiologist held the patient’s head, two assistants held the patient’s shoulders, two assistants held the patient’s legs, and the surgeon compressed the convex side of the spine by holding the contralateral pelvis and pushing the scoliosis apex site by another hand. Manual reduction began with gentle traction of the trunk by the leg assistants with greater force on the concave side and, simultaneously, the surgeon gradually increased the pushing force on the spine of the convex side. After manual reduction, all workers just gently put down and leave the patient in prone position. Flexible scoliosis was easily reduced by the manual procedure, leaving a substantial disc opening on the concave side. However, when ankylosing scoliosis is encountered, it cannot be reduced manually, and a spur discontinuity procedure is needed thereafter.

Figure 2: Body-disc cement bonding was performed via extrapedicle access to the cranial body endplate, and retrograding vertebroplasty was performed first with cement bridging to the disc cement (A to F; A1 to A5). Disc-body cement bonding was achieved by transpedicular access to the cranial disc and retrograding cement discoplasty with bridging to the body cement (G to L; B1 toB5).

The puncture was performed using extrapedicular access to keep the puncture trocar in the intervertebral disc space and continuously penetrate and stop at the lower endplate of the cranial vertebral body. Subsequently, the cement was injected about 1012 cc retrogradely into the cranial body. Meanwhile, the working channel was drawn backward with cement rooting from the body to the disc, and the puncture trocar was reinserted into the anterior part of the disc space. Subsequently, 4-6 cc of cement was injected into the disc space, bridging the body cement. If the amount of cement in retrograding vertebroplasty is insufficient, for example, less than 9cc into the body, which may increase the risk of compression fractures in severe osteoporosis cases, vertebroplasty via contralateral transpedicle access should be performed. There are three mechanisms for correcting spinal deformities in PIBC: manual reduction, trocar manipulation, and disc distraction by cement injection. Among these, manual reduction is crucial for significant correction, whereas trocar manipulation and cement distraction provide minor realignment.

Operative Procedures of OIBC

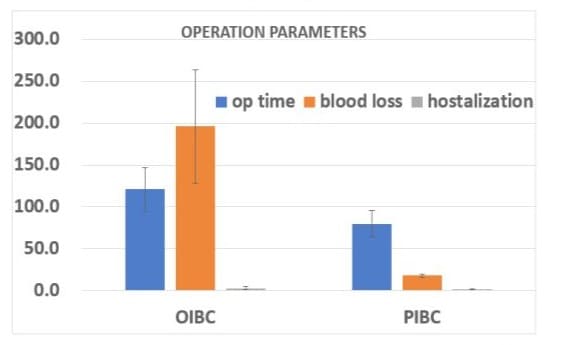

The midline spinal process tips were marked, and an incision was made approximately 3-4 cm away from the midline on the concave side. One incision was approximately 3 cm long to allow OIBC for two continuous discs. Through the Kambin triangle, one trocar was inserted into the target disc and the disc space was enlarged by serial trials. Subsequently, a 1-cm curette was used to create bony cavities at both adjacent vertebrae. Cement (9-15 ml) was inserted into the disc space and the created bony cavities, which was solidified as a three-dimensional locking interbody fixator. The cage with lordosis angle was inserted before cement hardened to ensure interdigital cement-trabecula bonding. Because the cementbone bonding is poor to tensile force during spine extension, the interspinal process device (Rocker, Pao-Nan, Taiwan) was applied around the scoliosis apex segments to prevent spine extension and decrease the cement stress. If stenosis was still identified despite indirect decompression, unilateral foraminoplasty was performed. The back brace was not required (Figure 3).

Figure 3: A 75-year-old female with degenerative scoliosis 38’ and lumbar lordosis 14’ (A, B) underwent OIBC. Immediate postoperative scoliosis was 6’ and lumbar lordosis was 28’ (C, D). Five years later, scoliosis was 10’ and lumbar lordosis was 27’ (E, F).

Outcome Measures

Clinical evaluation was performed preoperatively and postoperatively at 3, 6, 12, and 24 months, and at the last followup. Overall, VAS score (0-10) and Oswestry Disability Index (ODI; 0-100) were used. For radiological analysis, cement loosening, disc space narrowing, index vertebral compression fractures, and adjacent segment pathology were evaluated. Complications at 30 days were recorded and classified as major and minor using the Glassman classification [13]. Major complications were defined as those leading to permanent neural deficit or permanent neural impairment, whereas minor complications were defined as those that did not result in permanent damage and no subsequent reoperation.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables are described as absolute and relative frequencies with percentages. Quantitative variables are described as the mean ± standard deviation. The intergroup preoperative and postoperative radiographic and clinical data were compared using a non-paired t-test, and the statistical significance (p < 0.05) of these differences was calculated. Statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Office 365).

Results

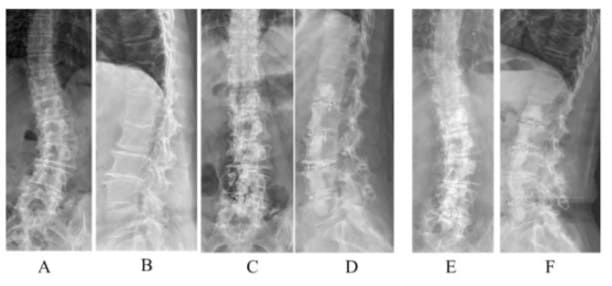

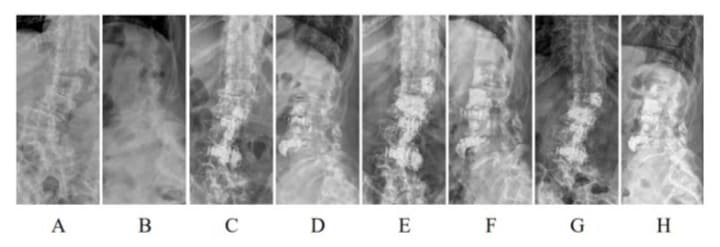

The operative time of OIBC vs. PIBC was 121 ± 26 vs. 80 ± 16 min with an estimated blood loss of 196 ± 68 vs. 18.0 ± 2 ml (p<0.001) and mean surgical motion segments were 4.4 ± 0.4 vs. 4.1 ± 0.1. The mean hospitalization was 2.9 ± 1.6 vs.1.8 ± 0.8 D (p<0.001). (Figure 4) All patients were able to walk on the day of the operation. These two cases are highlighted and interpreted in Figures 5,6, respectively.

Figure 4: All operation parameters were significantly different between OIBC and PIBC groups.

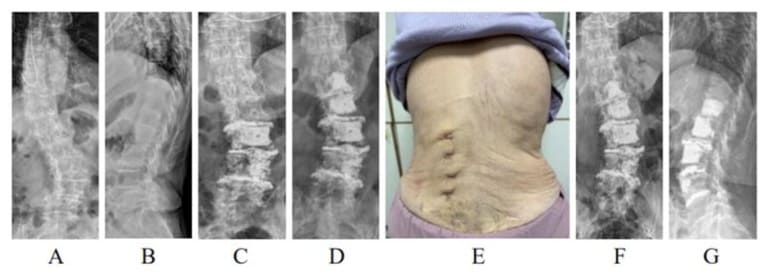

Figure 5: Case demonstration of a 53-year male patient with 26° DLS; A and B: pre-operation; C and D: post-operation 1-month followup; E and F: 78-month follow-up, G, H, and I: 9-year follow-up. He was symptom-free and enjoyed his life as an active farmer.

Figure 6: A 90-year-old female with degenerative scoliosis 36° (A, B) and polymorbidities. She was treated with PIBC under local anesthesia and stopped (C) owing to bradycardia after an injection of 20 mg of xylocaine. One week later, the patient underwent PIBC (D) under local anesthesia. The photograph shows trocar access (E). Postoperative scoliosis was 23° at the first PIBC (C), 19°, second PIBC (D), and 22° 12 months later (F, G).

Overall Clinical Result: VAS and ODI

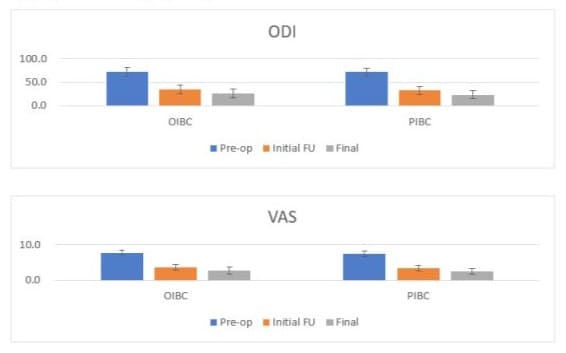

Preoperative VAS and ODI of OIBC and PIBC were 7.9 ± 0.7 and 72.8 ± 8.7 vs. 7.7 ± 0.8 and 71.9 ± 8.6, respectively. At the initial follow-up i.e. 7 days after operation, VAS and ODI were 3.7 ± 0.9 and 33.6 ± 9.7 vs. 3.3 ± 0.8 and 31.9 ± 8.7. At the final visit, VAS and ODI were 2.8 ± 1.1 and 24.3 ± 9.3 vs. 2.7 ± 1.2 and 24.7 ± 8.5. Significant postoperative improvements were noted in both groups; however, there were no intergroup differences (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Both ODI and VAS had significant postoperative improvements in two groups.

Radiological Findings

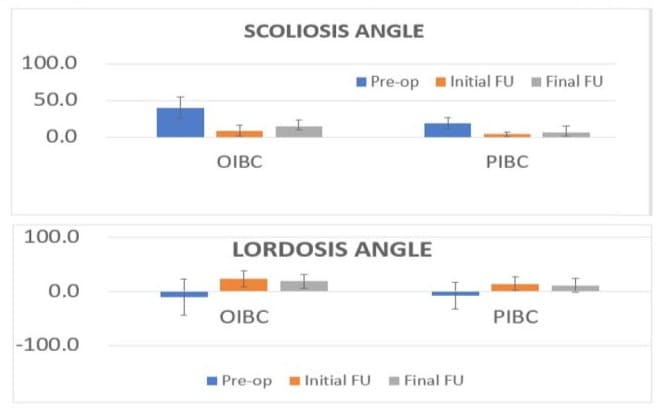

The preoperative Cobb’s angles of OIBC and PIBC were 40.1° ± 14.6° vs. 18.8° ± 7.8° and 8.5° ± 7.4° vs. 3.7° ± 3.5° at the 24 h follow-up and 14.6° ± 9.4° vs. 6.2° ± 4.4° at the final visit. Preoperative lumbar lordosis angles were -10.6° ± 33.8° vs. -7.8°± 24.3° (p=0.70) and 23.2° ± 15.1° vs. 13.9° ± 12.8° (p=0.003) at the 24 h follow-up and 18.3° ± 12.8° vs. 11.2° ± 13.3° (p=0.02), respectively, at the final visit.

(Figure 8) The initial correction of scoliosis was 31.6° ± 10.2° vs. 15.1° ± 5.2° (p<0.001) and that of lordosis was 33.8° ± 21.9° vs. 21.7° ± 13.1° (p<0.001). The final correction of scoliosis was 25.5° ± 10.3° vs. 12.6° ± 5.2° (p<0.001), and lordosis was 28.9° ± 24.0° vs. 19.0° ± 13.1° (p=0.02). Significant improvements in lumbar lordosis and Cobb angle were observed in both the groups (Figures 9&10).

Figure 8: Both scoliosis and lumbar lordosis were improved significantly in two groups.

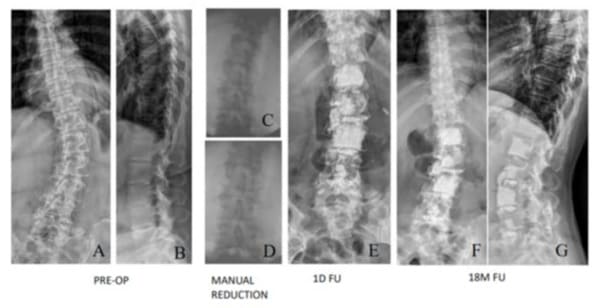

Figure 9: A 60-year-old female with degenerative scoliosis (A, B) underwent L2/S1 OIBC. One-month follow-up showed good correction (C, D). The patient remained symptom-free at the final follow-up after six years. (E, F).

Figure 10: A 79-year-old female with degenerative scoliosis 40° and lumbar kyphosis 34° (A, B) underwent PIBC. Immediate postoperative scoliosis was 5° and lumbar lordosis was 13° (C, D). Eighteen months later, the scoliosis was 3° and lumbar lordosis was 5° (E, F). Asymptomatic cement leakage was observed on the ventral side of the L1 vertebral body.

Figure 11: A 75-year-old female with degenerative scoliosis of 43° and lumbar lordosis of 36° (A, B) underwent L2/4 OIBC. Immediate postoperative scoliosis was 5° and lumbar lordosis was 48° (C, D). She underwent L1/2 PIBC 41 days later. (E, F), which was wellmaintained at the final follow-up at one year (G, H).

Complications

Surgical complications included asymptomatic cement leakage in 21 OIBC and 15 PIBC cases. Most of them were due to annular fibrosa breakage during correction of scoliosis, and the cement went to the anterior-lateral paravertebral space. Two OIBC and one PIBC patients had symptomatic cement leakage and required revision surgery. While correction of scoliosis, the stress at the concave side is much higher and may lead to compression fractures; two cases (6.4%) were noted in the current authors’ series. No infection, nerve injury, or symptomatic hematoma was observed. At the final visit, asymptomatic cement loosening with a localized halo sign in the cemented construct was noted in eight OIBC and 4 PIBC patients without further management. Four patients had silent proximal adjacent or remote wedge fractures, which were left for observation. Seven patients (six with OIBC and two with PIBC) experienced at least one complication in post-operative 30 days; among them, five cases (17.7%) were considered minor, including postoperative radiculopathy (three cases), superficial skin infection (1), and urinary tract infection (1). Two patients in the OIBC group and one, in the PIBC group had symptomatic cement leakage and required revision surgery.

Additional PIBC

This study performed additional PIBC in four patients (2 in the OIBC group and 2 in the PIBC group) (Figure 11) immediately cranial to the previous IBC due to symptomatic junctional scoliosis with radiculopathy.

Discussion

PCD can avoid open surgery and good for elders, but poor to correct scoliosis and lumbar lordosis [3], indicating that PCD cannot correct coronal imbalance. A mini-open IBC was reported, which can additionally correct scoliosis and lumbar lordosis with the advantages of a small wound, no bone graft, and no instrumentation [11]. To further minimize the invasiveness of surgery and anesthesia risks, PIBC under local anesthesia was developed. This study retrospectively confirmed the role of PIBC in treating degenerative scoliosis with polymorbid and complicated medical conditions. Compared with the literature on traditional surgery for DLS [14-20], the complication and reoperation rates of OIBC and PIBC were relatively low. The reoperation rate of traditional fusion surgery for DLS was between 26% and 44% after a mean follow-up of 5-6 years [14,15,18-20]. Carreon et al. [17] reported as high as 79.6% complication rate in elder greater than 65 years receiving posterior decompression and fusion including 21.4% major complications and 50% two or more complications. Thus, OIBC and PIBC could provide alternative options, especially for selected cases with a higher risk of complications. After correction of the spinal deformity, long-term postoperative stability is a major concern, but not bony fusion. In Li’s report [11], no patient needed revision due to symptomatic cement loosening, with a mean follow-up of 6 years. The two possible mechanisms proposed by Li et al. were further stabilized by spontaneous ankylosing spur formation and the insensibility of micromotion caused by cement loosening. In addition, symptomatic cement loosening can be treated by percutaneous transpedicle vertebroplasty to re-stabilize the spine construct, which is relatively easy and can be performed under local anesthesia.

Based on this retrospective report, the indirect neural decompression effect of OIBC or PIBC realignment is dependable. The success rate of indirect neural decompression has been reported to be high and the failure rate is exceedingly low. [21-24] According to the experiences of lateral lumbar interbody fusion [25], the indirect effects include 68% increase in vertebral canal area, 60-68% increase in foramen area, 29-32% increase in foramen height, and 18% reduction in ligamentum flavum thickness. In addition, older age, presence of spondylolisthesis, presence of intra-articular facet effusion, and posterior height of the interbody fusion cage may affect the increase in the canal area. Manual reduction to correct scoliosis and listhesis may play a key role in achieving indirect neural decompression in both OIBC and PIBC patients. In PIBC, the correction of deformities and indirect decompression can be further achieved by manipulating trocar pushers and disc cement distraction force. The clinical results of this study showed that indirect decompression was expected to be successful. This retrospective study had some limitations. First, it is not a random design with selection bias, and the small sample size might have reduced the strength of this study. Second, this was a single-center study. Third, the follow-up time was limited to three years, which may not have been long enough. Further multi-center, prospective, long-term studies involving a larger sample size would be better understood.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that both OIBC and PIBC led to significant VAS and ODI improvements and wellmaintained correction of scoliosis and lordosis with a mean 3-year follow-up. The operation time, blood loss, hospitalization, and complication rates of PIBC were lower than those of OIBC. PIBC can be regarded as a potential alternative option for DLS patients with polymorbidities who are not suitable for general anesthesia and open surgery.

Funding: No source of funding.

Declarations: Conflict of interest: None of the authors have any potential conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval: This study enrolled only patients who agreed to participate in the study after being informed the surgery treatment approved by the ethics committee of St. Martin De Porres Hospital, Chia-Yi, Taiwan (approval number, IRB 24C-001). All participants individually provided written informed consent. All study methods were conducted in accordance with the guidelines set out in the Declaration of Helsinki.

References

- Schwab F, Dubey A, Gamez L, El Fegoun AB, Hwang K, et al. (2005) Adult scoliosis: prevalence, SF-36, and nutritional parameters in an elderly volunteer population. Spine 30: 1082-1085.

- Hoy D, Bain C, Williams G, March L, Brooks P, et al. (2012) A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain. Arthritis Rheum 64: 2028-2037.

- Daubs MD, Lenke LG, Cheh G, Stobbs G, Bridwell KH (2007) Adult spinal deformity surgery: complications and outcomes in patients over age 60. Spine 32: 2238-2244.

- Camino-Willhuber G, Guiroy A, Servidio M, Astur N, Nin-Vilaró F, et al. (2023) Unplanned readmission following early postoperative complications after fusion surgery in adult spine deformity: A multicentric study. Global Spine J 13: 74-80.

- Camino-Willhuber G, Norotte G, Bronsard N, Kido G, Pereira-Duarte M, et al. (2021) Percutaneous cement discoplasty for degenerative low back pain with vacuum phenomenon: a multicentric study with a minimum of 2 years of follow-up. World Neurosurg 155: e210-e217.

- Varga P, Jakab G, Bors I, Lazary A, Szövérfi Z (2015) Experiences with PMMA cement as a stand-alone intervertebral spacer. Percutaneous cement discoplasty in the case of vacuum phenomenon within lumbar intervertebral discs. Der Orthopade 44: 124-131.

- Sola C, Camino Willhuber G, Kido G, Pereira Duarte M, Bendersky M, et al. (2021) Percutaneous cement discoplasty for the treatment of advanced degenerative disk disease in elderly patients. Eur Spine J 30: 2200-2208.

- Kiss L, Varga PP, Szoverfi Z, Jakab G, Eltes PE, et al. (2019) Indirect foraminal decompression and improvement in the lumbar alignment after percutaneous cement discoplasty. Eur Spine J 28: 1441-1447.

- Camino Willhuber G, Kido G, Pereira Duarte M, Estefan M, Bendersky M, et al. (2020) Percutaneous cement discoplasty for the treatment of advanced degenerative disc conditions: a case series analysis. Global Spine J 10 729-734.

- Yamada K, Nakamae T, Nakanishi K, Kamei N, Hiramatsu T, et al. (2021) Long-term outcome of targeted therapy for low back pain in elderly degenerative lumbar scoliosis. Eur Spine J 30: 2020-2032.

- Li KC, Hsieh CH, Liao TH (2023) Clinical outcome-supported advance of cement lumber interbody fusion for degenerative lumbar scoliosis. J Surg 8.

- Schizas C, Theumann N, Burn A, Tansey R, Wardlaw D, et al. (2010) Qualitative grading of severity of lumbar spinal stenosis based on the morphology of the dural sac on magnetic resonance images. Spine 35: 1919-1924.

- Glassman SD, Hamill CL, Bridwell KH, Schwab FJ, Dimar JR, et al. (2007) The impact of perioperative complications on clinical outcome in adult deformity surgery. Spine 32: 2764-2770.

- Yuan L, Zeng Y, Chen Z, Li W, Zhang X, et al. (2020) Risk factors associated with failure to reach minimal clinically important difference after correction surgery in patients with degenerative lumbar scoliosis. Spine 45: E1669-E1676.

- Charosky S, Guigui P, Blamoutier A, Roussouly P, Chopin D (2012) Complications and risk factors of primary adult scoliosis surgery: a multicenter study of 306 patients. Spine 37: 693-700.

- Deyo RA (2015) Fusion surgery for lumbar degenerative disc disease: still more questions than answers. Spine J 15: 272-274.

- Carreon LY, Puno RM, Dimar JR, Glassman SD, Johnson JR (2003) Perioperative complications of posterior lumbar decompression and arthrodesis in older adults. J Bone Joint Surg Am 85: 2089-2092.

- Puvanesarajah V, Cancienne JM, Werner BC, Jain A, Singla A, et al. (2018) Perioperative complications associated with posterolateral spine fusions: a study of elderly medicare beneficiaries. Spine 43: 1621.

- Cheng T, Gerdhem P (2018) Outcome of surgery for degenerative lumbar scoliosis: an observational study using the Swedish Spine register. Eur Spine J 27: 622-629.

- Brodke DS, Annis P, Lawrence BD, Woodbury AM, Daubs MD (2013) Reoperation and revision rates of 3 surgical treatment methods for lumbar stenosis associated with degenerative scoliosis and spondylolisthesis. Spine 38: 2287-2294.

- Thomas JA, Thomason CIM, Braly BA, Menezes CM (2020) Rate of failure of indirect decompression in lateral single-position surgery: clinical results. Neurosurg Focus 49: E5.

- Walker CT, Xu DS, Cole TS, Alhilali LM, Godzik J, et al. (2021) Predictors of indirect neural decompression in minimally invasive transpsoas lateral lumbar interbody fusion. J Neurosurg Spine 35: 8090.

- Shimizu T, Fujibayashi S, Otsuki B, Murata K, Matsuda S (2020) Indirect Decompression Through Oblique Lateral Interbody Fusion for Revision Surgery After Lumbar Decompression. World Neurosurg 141: e389-e399.

- Park J, Park SM, Han S, Jeon Y, Hong JY (2023) Factors affecting successful immediate indirect decompression in oblique lateral interbody fusion in lumbar spinal stenosis patients. N Am Spine Soc J 16: 100279.

- Petrone S, Ajello M, Marengo N, Bozzaro M, Pesaresi A, et al. (2023) Clinical outcomes, MRI evaluation and predictive factors of indirect decompression with lateral transpsoas approach for lumbar interbody fusion: a multicenter experience. Front Surg 10: 1158836.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.