Laparoscopic Adrenalectomy for Pediatric Pheochromocytoma: Case Report and Literature Review

by Dora Persichetti Proietti1, Sara Maria Cravano2*, Alessandra Cazzuffi1, Cristian Succi1, Enrica Rossi1, Maria Elena Michelini1, Eleonora Cesca1, Claudio Vella1

1Azienda Ospedaliera-Universitaria di Ferrara, Via Aldo Moro, Ferrara, Italy 2Policlinico Sant’Orsola-Malpighi, Via Massarenti, Bologna, Italy

*Corresponding author: Sara Maria Cravano, Policlinico Sant’Orsola-Malpighi, Via Massarenti, Bologna, Italy

Received Date: 04 October 2023

Accepted Date: 11 October 2023

Published Date: 16 October 2023.

Citation: Proietti DP, Cravano SM, Cazzuffi A, Succi C, Rossi E, et al. (2023) Laparoscopic Adrenalectomy for Pediatric Pheochromocytoma: Case Report and Literature Review. Arch Pediatr 8: 294. https://doi.org/10.29011/2575-825X.100294

Abstract

Pheochromocytoma is a rare neuroendocrine tumor, that originates from chromaffin cells of the adrenal glands. It may be sporadic or in the context of a hereditary syndrome. Furthermore, pheochromocytoma causes secondary hypertension and increases cardiovascular morbidity due to an excess of circulating catecholamines. Diagnosis is confirmed by elevated plasma or urinary levels of metanephrines or normetanephrines; instead, radiological images are useful for the tumor location and for identifying any metastases. Surgical resection is the definitive treatment. Laparoscopic approach is spreading in many Pediatric Surgery Units worldwide. The successful outcome of the mini-invasive technique is influenced by different factors, such as tumor volume, adrenal vessels characteristics, presence of adjacent organ infiltration, and also surgeons experience.

This paper aims to share our experience with a recent case of pediatric pheocromocytoma, approached and successfully removed by transperitoneal laparoscopic technique, and to share literature review of the last 10 years on the state of art of the laparoscopic approach for this kind of tumors in pediatric population.

Keywords: Pheochromocytoma; Neuroendrocrine System; Laparoscopy; Hypertension; Case Report; Adrenalecomy.

Introduction

Pheochromocytoma is a rare tumor arising from the chromaffin neuroendrocine cells located in the adrenal gland’s medulla and in other sympathetic nervous system ganglia. According to the WHO classification, pheochromocytomas (80%) originate in the adrenal medulla, while extra-adrenal masses, that can be located in different parts of the body, like abdomen, thorax, pelvis, and neck, are defined paragangliomas (20%). Pheochromocytoma produces and secretes catecholamines (epinephrine, norepinephrine, dopamine) [1]. The annual incidence is reported to be about 1 in 300,000 worldwide, and 20% of all these tumors are diagnosed in childhood and adolescence. . In children diagnosed with blood hypertension up to 1.7% have a catecholamine secreting neoplasm [2]. Pheochromocytoma and paragangliomas may be sporadic masses or involved in the context of an hereditary syndrome. Therefore, all patients diagnosticated with a pheochromocytoma should undergo genetic testing, that guarantee useful informations that can be valuable in screening, diagnosis, and prognostication of hereditary pheochromocytoma [3]. In children, the mean age of onset is among 11 and 13 years with a male preponderance of 2:1 [4-5]. The symptoms can be caused either by catecholamines overproduction, local pressure of the mass or metastasis presence [6]. Typical symptoms of catecholamine excess include diaphoresis, headaches, and palpitations. A long-standing hypertension may precipitate organs damage in heart, kidney, eyes, and central nervous system and deregulate glucose metabolism causing diabetes [7]. Therefore, prompt diagnosis is required, through clinical features, blood and urine exams, and radiological images.

The gold standard for treatment remains surgical resection. Surgical manipulation of tumor can lead to a massive release of catecholamines into circulation and may cause hypertensive crisis, cardiac arrhythmias, myocardial ischemia, pulmonary edema, and stroke. So, perioperative antihypertensive therapy is mandatory to avoid hypertensive peaks during anesthetic induction and surgical procedure and to prevent postoperative hypotension after tumor resection. Preoperative preparation is the same as with adults: adequate pre-operative α-adrenergic receptor blockers has been proven to reduce perioperative complications to less than 3% [8]. since they prevent intraoperative hemodynamic instability during mass resection; β-adrenoceptor blockers may be used for preoperative control of tachyarrhythmias or angina. However, loss of β-adrenoceptor-mediated vasodilatation in a patient with unopposed catecholamine-induced vasoconstriction can result in dangerous hypertension. Therefore, an α-adrenergic receptor blocker, that mediates vasoconstriction, should always be administered before employing β-adrenoceptor blockers [9].

Recent progresses in minimally invasive surgery are improving the feasibility and safety of laparoscopic adrenalectomy for non-malignant tumours, and it seems to reduce the “catecholamines storm” during operation. Also in pediatric surgery, laparoscopic approach finds wide application.

In particular, laparoscopic adrenalectomy has been accepted as the “gold standard” treatment modality for small-sized (<6 cm) pheochromocytomas and has been used for resection of largesized (>6 cm) masses [10].

We report a case of laparoscopic adrenalectomy in an 11-year-old patient with pheochromocytoma.

Case report

An 11-year-old boy attended the Ferrara University Hospital Pediatric Emergency Room, because of a long-lasting frontal headache associated with blood pressure values > 99th percentile for age. In ER, blood pressure was measured at intervals of about 5-10 minutes with an automatic cuff: mean systolic blood pressure was 151-160 and mean diastolic blood pressure was 105-117 mmHg. Blood analysis showed normal blood counts, normal kidney and liver function, CK-MB and Troponin I was in range of normality. ECG also showed regular parameters. The 24h-urine analysis, revealed elevated levels of norepinephrine (996.83 μg/24h). Serum levels of aldosterone, cortisol, parathyroid hormone, ACTH, calcitonin, and renin were normal.

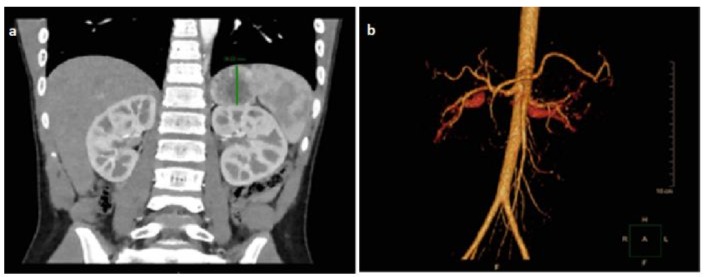

Abdominal ultrasound revealed the presence of a 35x40x50 mm solid mass in the left adrenal site. Therefore, a CT-scan was performed. The mass presented inhomogeneous enhancement in arteriovenous phase, with a large central necrotic area, in close contiguity with the spleen and the upper pole of the left kidney. Kidney infiltration was suspected. Adrenal vessels were hypertrophic (Figure 1a and b).

Figure 1: Patient CT-scan showing the mass location and the anatomic infiltration (a) 3D reconstruction of adrenal vessels infiltration (b) Adrenal pheochromocytoma was the first diagnostic hypothesis.

During hospitalization, the patient underwent different clinical exams: genetic investigation, which didn’t highlight mutations in RET gene; ophthalmology consultation, normal; cardiological consultation, that confirmed hypertension associated to mild dilatation of the aortic root and right coronary tree, and outlined anti-hypertension therapy. The patients was referred to our Pediatric Surgery Unit. Doxazosin was administered at a starting dose of 1 mg / day (0.02 mg/kg), then increased up to 5 mg/day to normalize blood pressure before surgery. We decided to perform left laparoscopic adrenalectomy after 20 days of therapy, when blood pressure normalized. The patient has been placed in lateral decubitus with left side up (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Patient intraoperative position: right lateral decubitus with suspended arms, extended left leg and flexed right leg. The left side is exposed and the landmarks are tracked.

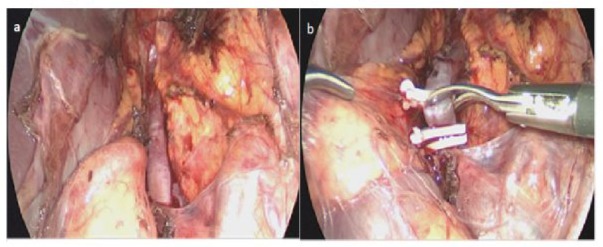

The surgery was performed under general anesthesia. The patient was intubated in supine position, and the anesthesiologist carried out rectus muscle nerve local block for better post-operative pain control. An urinary catheter and an adequate venous access were placed. Constant monitoring of vital signs, including blood pressure, oxygen saturation and ECG misuration, were performed throughout the surgery. Blood pressure was stabilized throughout the procedure by Urapidil Hydrochloride administration. Pneumoperitoneum was achieved through a 5 mm trocar, placed in the middle of a transverse line crossing the 11-th rib. Under direct vision, two 5 mm trocars were positioned on the midline, one at 10 cm from the xiphoid bones and the other on the left side, in order to obtain a correct triangulation of the left adrenal site. Then mobilization of the splenic flexure, splenorenal ligament and peritoneal fixation between the spleen and abdominal wall was performed with Thunderbeat® forceps. The Gerota’s fascia was incised with 5 mm Ligasure®. Once the mass was identified, no infiltration of the renal parenchyma was highlighted, the inferior adrenal vein (about 6-7 mm diameter) was isolated. Additional 5 mm and 12 mm trocars were helpful in the management of the central adrenal vein. The vein ligation was performed by Medium-Large clips placed with Weck Hem-o-lok ® system (Figure 3 a and b).

Figure 3 : Intraoperative findings: (a) hypertrophic inferior adrenal vein (b) and his ligation by Hem-o-lok clips

The lesion was completely removed and placed in a 10 mm endo bag, then extracted by a Pfannenstiel incision. The mobilized spleen was fixed with interrupted suture to the parietal peritoneum. The operation time was about 240 minutes. Macroscopic appearance was of a 6 x 3.5 x 4 cm solid, capsulated, yellow ocher nodular lesion. Neither pressure and hemodynamic decompensations occurred during the procedure. Histological examination confirmed an high cellularity phaeochromocytoma, with marked cellular pleomorphism, quietly vascularized, with focal areas of necrosis. The proliferative activity index evaluated with Ki67 was approximately 3%. Phenotypic characterization: chromogranin +. synaptophysin +, S100 + (sustentacular cells), CAM5.2-, INIB-. The patient was admitted to intensive care for 48 hours. The postoperative period was uneventful. Blood pressure was normal during the hospital stay, without any antihypertensive treatment. Follow-up after the hospital discharge was performed by the Pediatric Oncohematologic Unit. PET-CT, performed three months after surgery, showed no disease reactivation.

Discussion

Pheochromocytoma is a rare type of neoplasm in childhood and it is responsible for 1% of cases of secondary hypertension. The incidence of malignant pheochromocytoma is about 0.02 cases per million [11]. In literature, it’s reported that the presence of a sporadic lesion and a tumor diameter larger than 6 cm are statistically significant for malignancy [12-13].

Patients with benign lesions are considered healed after surgical resection. In particular, symptoms related to catecholamine excess disappear. Laparotomic access was the gold standard until 1992 when Gagner et al. reported the first laparoscopic adrenalectomy in an adult man [14]. Overtime, laparoscopic transperitoneal technique has gained popularity also in pediatric centers. Because of the low incidence of this neoplasm in childhood, we just found few pediatric cases in literature [15-17].

Table 1: Data derived from reviewed studies.*presence of bilateral lesion. |

The development of multicenter retrospective studies could better delineate, in the future, the feasibility and safety of the laparoscopic technique in pediatric population [18,19]. shows the most important studies with stronger evidence in literature (Table 1).

A quick analysis of the literature shows that the most common approach in children is the laparoscopic transperitoneal one. A 2017 European multicenter study recruited 68 patients undergoing laparoscopic adrenalectomy: transperitoneal approach was performed in 92.8% of the cases and retroperitoneal approach in the remaining 7.4%; no conversion to open surgery was necessary. The transperitoneal approach is also applicable for bulky masses, since it allows better exposure and bilateral control, and many surgeons are more confortable with it [16,18].It is widely accepted that the laparoscopic approach is a good and flexible procedure that offers good results [14-18]. A correct preoperative imaging is mandatory to avoid complications and to determine any risks of organ infiltration [19-20].

For a long time, laparoscopy was avoided in masses larger than 6 cm. Nowadays, according to some authors, volume itself is not a limit, but the presence of organ infiltration is still on debate [19]. The results of the European multicenter survey also shows how masses up to 145.6 cc (mean diameter 6.5 cm) have been completely removed with a minimally invasive technique, highlighting that there is no close relationship between tumor size and surgical outcomes [18-19]. Also local invasiveness tends to increase operative time and the risk of bleeding but doesn’t correlate with conversion rate or recurrence risk.

Moreover during laparoscopy the patient tends to mantain intraoperative hemodynamic stability. A recent meta-analysis of 628 patients showed that the laparoscopic technique is associated with lower rates of intraoperative hemodynamic and pressure instability and blood loss. Thanks to the laparoscopic instruments, the manipulation of the tumor is limited. The magnified field allows for early detection of the main adrenal vein which can be safely ligated, reducing the release of catecholamines [21].

Conclusion

Surgical resection remains the gold standard in case of pheochromocytoma. Laparoscopic technique has been successfully performed in many adult and pediatric patients. Laparoscopic adrenalectomy offers the benefits of minimally invasive surgery and a better intraoperative hemodynamic stability, and should be applied after a careful preoperative diagnostic evaluation of the patient. Furthermore, laparoscopic approach allows a minimal tumor manipulation with early control of the adrenal vein in comparison to open surgery. However, laparoscopy is associated with less intraoperative bleeding, shorter length of hospital stay, low morbidity, fewer complications and quick recovery. Conversion rate in pediatric age is still high (13-40%) as our review shows. Therefore, minimally invasive surgery should be perform if the surgeon is confident with the technique. Long-term follow-up is necessary because of recurrence risk. A check-up visit at 6 weeks, between 6 months to 1 year post surgery and then an annual surveillance are recommended.

However, for a real evaluation of the efficacy and all the advatages of the laparoscopic adrenalectomy for pediatric pheochromocytoma, large series of patients are required and several studies should be performed worldwide. In conclusion, laparoscopic removal of pheocromocitoma in pediatric population is feasible and suggested in terms of safety in selected cases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.P.P. and S.M.C.; Methodology, A.C.; Software, C.S.; Validation, C.V. and M.E.M.; Formal Analysis, D.P.P.; Investigation, E.R.; Resources, E.C.; Data Curation, S.M.C.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, D.P.P.; Writing – Review & Editing, S.M.C.; Visualization, A.C.; Supervision, C.V.; Project Administration, M.E.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of this manuscript.

Funding

This manuscript wasn’t financed by external funds.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was carried on according to the guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration.

Informed Consent Statement

We obtained the written informed consent from the patient to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the authors, but they aren’t publicly available.

Conflicts of Interest

All the authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lenders JW, Eisenhofer G, Mannelli M, Pacak K (2005) Phaeochromocytoma. Lancet 366: 665-675.

- Wyszynska T, Cichocka E, Wieteska-Klimczak A, Jobs K , Januszewicz P (1992) A Single Pediatric Center Experience with 1025 Children with Hypertension. Acta Paediatrica 81: 244-246.

- Gunawardane PTK, Grossman A (2017) The clinical genetics of phaeochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Arch Endocrinol Metab 61: 490-500.

- Ludwig AD, Feig DI, Brandt ML, Hicks MJ, Fitch ME, et al. (2007) Recent advances in the diagnosis and treatment of pheochromocytoma in children. Am J Surg 194: 792-796.

- Bholah R, Bunchman TE (2017) Review of Pediatric Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma. Front Pediatr 5: 155.

- Farrugia FA, Charalampopoulos A (2019) Pheochromocytoma. Endocr Regul 53: 191-212.

- Baguet JP, Hammer L, Mazzuco TL, Chabre O, Mallion JM, et al. (2004) Circumstances of discovery of phaeochromocytoma: A retrospective study of 41 consecutive patients. Eur J Endocrinol 150: 681-686.

- RE Goldstein, J A O’Neill Jr, GW Holcomb 3rd, W M Morgan 3rd, W W Neblett 3rd, , et al. (1999) Clinical experience over 48 years with pheochromocytoma. Ann Surg 229: 755-764.

- Lentschener C, Gaujoux S, Tesniere A, Dousset B (2011) Point of controversy: perioperative care of patients undergoing pheochromocytoma removal-time for a reappraisal? Eur J Endocrinol 165: 365-373.

- Wang W, Li P, Wang Y, Wang Y, Ma Z, et al. (2015) Effectiveness and safety of laparoscopic adrenalectomy oflarge pheochromocytoma: a prospective, nonrandomized, controlled study. The American Journal of Surgery 210: 230-235.

- Armstrong R, Sridhar M, Greenhalgh KL, Howell L, Jones C, et al. (2008) Phaeochromocytoma in children. Arch Dis Child 93: 899-904.

- Pham TH, Moir C, Thompson GB, Zarroug AE, Hamner CE, et al. (2006) Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma in children: a review of medical and surgical management at a tertiary care center. Pediatrics 118: 1109-1117.

- Traynor MD Jr, Sada A, Thompson GB, Moir CR, Bancos I, et al. (2020)Adrenalectomy for non-neuroblastic pathology in children. Pediatr Surg Int 36: 129-135.

- Gagner M, Lacroix A, Bolté E (1992) Laparoscopic adrenalectomy in Cushing’s syndrome and pheochromocytoma. N Engl J Med 327: 1033.

- Lima M, Gargano T, Al-Taher R, Antonio SD, Maffi M (2016) Laparoscopic surgery and hemodynamic changes duringadrenalectomy for pheochromcytoma in childhood: management of two cases and literature review.

- Mirallié E, Leclair MD, de Lagausie P, Weil D, Plattner V, et al. (2001) Laparoscopic adrenalectomy in children. Surg Endosc 15: 156-160

- Soheilipour F, Pazouki A, Ghorbanpour S, Tamannaie Z (2013) Laparoscopic adrenalectomy for pheochromocytoma in a child. APSP J Case Rep 4: 2.

- Fascetti-Leon F, Scotton G, Pio L, Beltrà R, Caione P, et al. (2017) Minimally invasive resection of adrenal masses in infants and children: results of a European multi-center survey. Surg Endosc 31: 45054512.

- St Peter SD, Valusek PA, Hill S, Wulkan ML, Shah SS, et al. (2011) Laparoscopic adrenalectomy in children: a multicenter experience. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 21: 647-649.

- Emre Ş, Özcan R, Bakır AC, Kuruğoğlu S, Çomunoğlu N, et al. (2020) Adrenal masses in children: Imaging, surgical treatment and outcome. Asian J Surg 43: 207-212.

- Fu SQ, Wang SY, Chen Q, Liu YT, Li ZL, et al. (2020) Laparoscopic versus open surgery for pheochromocytoma: a meta-analysis. BMC Surg 20: 167.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.