Intracranial Arterial Dissection and Syphilitic Aortitis: An Unusual Dual Vascular Manifestation

by Rim Moufakkir*, Houyam Tibar, Hajar Naciri Darai, Dahab Ouhabi, Wafa Regragui

Neurology B and Neurogenetics Department, Specialties Hospital, Rabat, Morocco.

*Corresponding author: Rim Moufakkir, Neurology B and Neurogenetics Department, Specialties Hospital, Rabat, Morocco

Received Date: 18 April, 2025

Accepted Date: 26 April, 2025

Published Date: 16 May, 2025

Citation: Moufakkir R, Tibar H, Darai HN, Ouhabi D, Regraguy W. (2025) Intracranial Arterial Dissection and Syphilitic Aortitis: An Unusual Dual Vascular Manifestation. Int J Cerebrovasc Dis Stroke 08: 197. https://doi.org/10.29011/2688-8734.100197

Abstract

Treponema pallidum is the causative agent of syphilis, a persistent, multisystemic illness. Since the advent of antibiotics, syphilis has become much less common, but in recent years, it has resurfaced all over the world. Cerebrovascular events including ischemic strokes and artery dissections can result from neurosyphilis, a serious late-stage consequence that can manifest as meningovascular syphilis. We report the case of a 26-year-old man with a history of drug abuse who presented with sudden-onset left hemiplegia, dysarthria, and Claude Bernard-Horner syndrome. Imaging revealed an ischemic stroke in the middle cerebral artery territory, associated with intracranial carotid and sylvian artery dissection. Further investigations uncovered mitro-aortic infective endocarditis complicated by severe aortic regurgitation and aortic abscess. Serologic testing confirmed active syphilis, suggesting a rare presentation of neurosyphilis with both meningovascular and cardiovascular involvement. The patient was treated with intravenous antibiotics, and aortic valve replacement was indicated.

Vasculitis, endarteritis, and arterial wall weakening are all possible side effects of meningovascular syphilis that put afflicted vessels at risk for dissection and aneurysm development. Diagnostic difficulties arise when neurosyphilis and syphilitic aortitis cooccur, especially when attempting to differentiate between infective endocarditis and syphilitic aortic regurgitation. This instance emphasizes that young stroke patients with unusual risk factors require comprehensive vascular examination and cutting-edge serological testing. Intracranial arterial dissection in the context of syphilitic aortitis is rare but serious. Prompt recognition and tailored management, including antibiotic therapy and vascular monitoring, are crucial to prevent complications. Increased awareness of neurosyphilis-related vascular events may improve early diagnosis and patient outcomes.

Keywords: Neurosyphilis; Syphilitic aortitis; Intracranial arterial dissection; Ischemic stroke.

Introduction

Syphilis is a type of chronic, multisystemic infection caused by Treponema pallidum bacteria. It used to be a common cause of stroke in young people due to the neurological complications of syphilis-before antibiotics were discovered, of course. Even with extensive use of antibiotics, there’s been a worrying increase in syphilis cases worldwide.

The infection can lead to some serious central nervous system problems like hemorrhagic and ischemic strokes. Recent studies on syphilis lesions and vascular dissections affecting the brain have provided a better understanding of both cerebrovascular disease and syphilis. These studies focus on more recently discussed mechanisms such as endothelial dysfunction [1].

This paper discusses the rare combination of syphilitic aortitis and intracranial arterial dissection. These details emphasize the need for diagnosed cerebrovascular diseases with strokes of undetermined etiology in younger patients, especially when the presentation deviates from the typical clinical picture.

Case Presentation

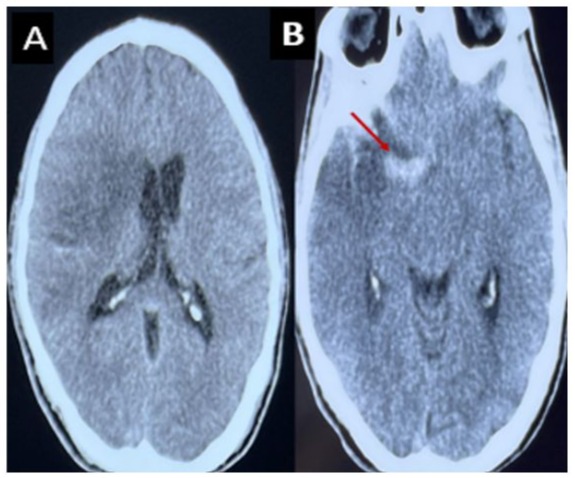

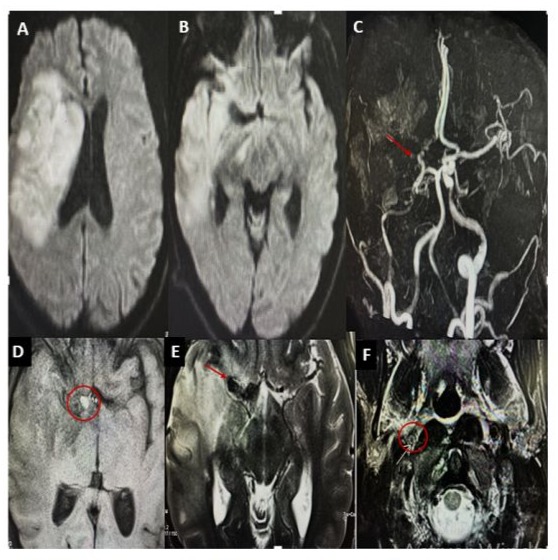

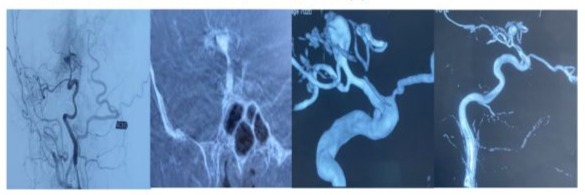

H.E a 26-year-old man with a history of active smoking, cannabis use, and chronic alcohol consumption. He had no history of recurrent tonsillitis, childhood heart disease, autoimmune disorders, known hereditary diseases, cervical trauma, or heavy lifting. He was admitted to the neurological emergency unit 3 days after sudden onset of proportional left hemiplegia, dysarthria, and Claude Bernard-Horner syndrome. An urgent brain CT scan revealed an ischemic stroke in the middle cerebral artery territory with a hyperdense sylvian artery sign (Figure 1). Brain MRI showed an intracranial dissection of the right carotid and sylvian arteries (Figure 2). One week later, digital subtraction angiography revealed a pseudoaneurysmal dilation at the origin of the right sylvian artery, resulting from the progression of the intracranial dissection (Figure 3). The patient was placed on antiplatelet therapy. The etiological assessment of his ischemic stroke revealed mitro-aortic infective endocarditis complicated by an abscess of the membranous septum, severe aortic regurgitation, and moderate mitral regurgitation. Notably, his initial Transthoracic Echocardiography (TTE) six days prior revealed infected endocarditis without concomitant valvulopathy. Blood cultures were negative. Biological analyses showed absence of inflammatory syndrome with negative Procalcitonin, positive TPHA and VDRL serology in the blood, while Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) analysis revealed a clear, normotensive fluid with normal biochemical and bacteriological findings and negative TPHA and VDRL serology in the Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF), the other serologies (serology of hepatitis B and C, HIV) were negative. The patient received intravenous antibiotic therapy with ceftriaxone (2g/day) for six weeks and gentamicin (160mg/day) for two weeks, with an indication for valve replacement surgery. Neurological deficits partially regressed (NIHSS at first day=9, at one month=5, and at three months=2, with a modified Rankin Scale score of 3 at three months).

Figure 1: CT scan without contrast, axial section showing a right deep and superficial sylvian ischemic stroke with mass effect on the homolateral ventricles (A). Spontaneously hyperdense appearance of the right Sylvian artery (B).

Figure 2: Brain MRI shows a right fronto-temporo-parietal hypersignal with mass effect on the ipsilateral ventricles (A–B). Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) reveals total occlusion of the right middle cerebral artery (MCA) and hypoplasia of the right internal carotid artery (ICA) and the A1 segment of the anterior cerebral artery (C). A nodular formation, hypointense on T2-weighted images and hyperintense on T1-weighted images, is observed at the level of the carotid terminus (D–E). A hyperintense crescent on T2weighted imaging, consistent with an intramural hematoma, is also visible (F).

Figure 3: Three-dimensional angiography demonstrating pseudoaneurysmal dilation at the origin of the right sylvian artery with small caliber appearance of the internal carotid artery with spasms indicating the presence of vascular pathology in a drug user.

Discussion

A rare but significant cause of infectious vasculitis is neurosyphilis, a kind of Treponema pallidum infection that affects the Central Nervous System (CNS). Both vascular and brain tissues have a special attraction for this spirochete. Prior to the development of antibiotics, one of the main causes of stroke in young adults was neurosyphilis, especially in its meningovascular form [2]. In the tertiary stage of syphilis, the illness usually manifests years after the original infection, frequently between 10 and 40 years later [3]. Treponema pallidum avoids immune clearance in its early stages by surviving in immuno-privileged areas such as the eye and central nervous system [4, 5].

Chronic inflammation brought on by CNS involvement causes endarteritis, which is typified by intimal hyperplasia and lymphocytic infiltration. Small to medium-sized intracranial arteries, meningeal vessels, and occasionally bigger arteries near the base of the brain are all constricted and occluded by this process. The vascular wall may become more vulnerable to dissection or aneurysmal dilatation as its structural integrity deteriorates [6].

Syphilitic vasculitis can result in carotid artery dissection, albeit this is uncommon. Prior studies have reported cases of recurrent strokes in patients with serologic evidence of a previous Treponema infection, with angiographic findings demonstrating extensive intracranial and extracranial vascular involvement [7], as well as bilateral internal carotid dissections in patients with a history of syphilis [8]. An autopsy revealed vertebrobasilar blockage in one extremely severe instance, which was suggestive of meningovascular syphilis [9].

Clinical suspicion, CSF abnormalities (pleocytosis and increased protein), and serologic testing are the basis for diagnosing neurosyphilis. While a negative result does not rule out the diagnosis, a positive VDRL in the CSF is quite specific for neurosyphilis [10].

The clinical picture of our patient was further confounded by the presence of syphilitic aortitis. Cardiovascular involvement was once a frequent late consequence of untreated syphilis. It can manifest as coronary ostial stenosis, saccular aneurysms, or aortic regurgitation [11]. Since both syphilitic aortic disease and infective endocarditis can manifest with valve dysfunction, distinguishing between the two conditions is a crucial diagnostic problem. The course of syphilitic aortitis is typically sluggish and subtle, frequently with no systemic symptoms of infection. On the other hand, infective endocarditis usually progresses quickly and exhibits strong infectious and inflammatory signs. Syphilitic aortitis typically results in negative blood cultures, which are typically positive in cases of bacterial endocarditis [11, 12].

It is rare for histopathological analysis of impacted valves to produce definitive results. Consequently, it is important to take into account the potential for concomitant syphilitic aortitis and infective endocarditis in instances that are unclear [13]. In our instance, syphilitic aortitis was the predominant cause, as evidenced by the absence of systemic inflammation, negative blood cultures, increasing valvular dysfunction, and positive serologic testing for syphilis [14].

Penicillin G is usually administered intravenously for 10–14 days at doses of 18–24 million units per day to treat neurosyphilis and cardiovascular syphilis. Doxycycline (100 mg twice daily) or tetracycline (500 mg four times daily) can be used for 30 days in patients who are allergic to penicillins. An acceptable substitute that enables outpatient treatment is ceftriaxone (2 g daily for 14 days) [15, 16]. Surgery must be used in conjunction with medical treatment when there is syphilitic aortic involvement, particularly if there is severe valve disease [17].

Surgery must be used in conjunction with medical treatment when there is syphilitic aortic involvement, particularly if there is severe valve disease [17].

Despite being uncommon, intracranial dissection is a dangerous disorder that needs to be treated on an individual basis. Antiplatelet or anticoagulant medication and, in certain situations, endovascular or surgical repair are possible forms of treatment. Current research indicates that there is insufficient evidence to support the use of either antiplatelets or anticoagulants, and that clinical presentation and imaging results are typically used to make judgments [18].

Conclusions

A very uncommon but possibly fatal vascular consequence of tertiary syphilis is intracranial artery dissection linked to syphilitic aortitis. This case illustrates how late-stage Treponema pallidum infections can present with a variety of vascular symptoms, some of which are unexpected. When a young patient presents with a stroke and there are serologic signs of syphilis and no traditional risk factors, clinicians should be extremely suspicious about syphilis. Clinical evaluation, neuroimaging, and specific serological and CSF investigations are all necessary for an accurate diagnosis. The cornerstone of treatment continues to be the prompt beginning of effective antibiotic medication; in patients with considerable cardiovascular involvement, surgical intervention may be necessary. Raising awareness of these unusual appearances can help guarantee early identification and treatment, which will eventually improve results and lower the risk of longterm neurological impairment and recurrent vascular episodes.

References

- S Lachaud, L Suissa (2010) Infarctus cérébral et infection VIH et syphilis meningovasculaire : étude de trois cas. 166: 76-82.

- Ropper AH (2019) Neurosyphilis. N Engl J Med 381: 1358-1363.

- Clark EG, Danbolt M (1995) The Oslo study of the natural course of untreated syphilis: An epidemiologic investigation based on a restudy of the Boeck-Bruusgaard material; a review andd appraisal. J Chron Dis 2: 311-344.

- Hook EW, Marra CM (1992) Acquired syphilis in adults. N Engl J Med 326: 10609.

- Chahine LM, Khoriaty RN, Tomford WJ, Hussain MS (2011) The changing face of neurosyphilis. Int J Stroke 6: 136-143.

- Bourazza A, Kerouache A, Reda R, Mounach J, Mosseddaq R (2008) Meningovascular syphilis: study of five cases. Rev Neurol Paris 164: 369-373.

- Marangi A, Moretto G, Cappellari M, Micheletti N, Tomelleri G, et al. (2016) Bilateral internal carotid artery dissection associated with prior syphilis: A case report and review of the literature. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 10:1351-1354.

- Aldrich MS, Burke JM, Gulati SM (1983) Angiographic findings in a young man with recurrent stroke and positive Fluorescent Treponemal Antibody (FTA). Stroke 14: 1001-1004.

- Feng W, Caplan M, Matheus MG, Papamitsakis MI (2009) Meningovascular syphilis with fatal vertebrobasilar occlusion. Am J Med Sci 338: 169-171.

- Tholance Y, Laroche S, Bertrand A, Caudie C (2008) CSF: Diagnosis of neurosyphilis in a patient hospitalized for an acute brain stroke. Ann Biol Clin Paris 66: 561-565.

- M Revest, O Decaux, T Frouget (2005) Les aortites syphilitiques. Expérience d’un service de médecine interne. Rev Med Interne 27: 16-20.

- M Revest, O Decaux, C Cazalets (2007) Aortites thoraciques infectieuses: Implications microbiologiques, physiopathologiques et thérapeutiques. Rev Med Interne 28: 108-115.

- Koletsky S (1942) Syphilitic cardiovascular disease and bacterial endocarditis. Am Heart J 23: 208-223.

- H Aizawa, A Hasegawa, M Arai (1998) Bilateral coronary ostial stenosis and aortic regurgitation due to syphilitic aortitis. Intern Med 37: 56-59.

- Jourdes A, Bettuzzi T, Robineau, O Molina. La ceftriaxone est noninférieure à la pénicilline G dans le traitement de la neurosyphilis. Médecine et Maladies Infectieuses 50: S133-S134.

- French P, Gomberg M, Janier M (2009) IUSTI: 2008 European Guidelines on the Management of Syphilis. International Journal of STD & AIDS 20: 300-309.

- Janier M, Hegyi V, Dupin N (2014) 2014 European guideline on the management of syphilis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol JEADV28: 1581-1593.

- Ophélie O, Emmanuel H, Stéphanie L, Francesco P (2015) Diagnostic et traitement des dissections intracrâniennes révélées par un infarctus cérébral : à propos de 5 cas, Neurologique 43-44.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.