Inflammatory Pseudotumor of the Liver Arising After Covid-19: A Case Report and Literature Review

by Alma Liliana Kuljacha Gastélum1*, Eduardo Alfredo González Murillo2,

Jesús Hector Bermea Mendoza3

1Instituto de Salud Hepática Hospital Ángeles Valle Oriente, Monterrey, Mexico

2Oca Hospital, Monterrey, México

3Hospital Conchita Muguerza, Monterrey, México

*Corresponding author: Alma Liliana Kuljacha Gastélum, Instituto de Salud Hepática Hospital Ángeles Valle Oriente, Monterrey, Mexico

Received Date: 08 October 2024

Accepted Date: 14 October 2024

Published Date: 16 October 2024

Citation: Kuljacha-Gastélum AL, González-Murillo EA, Bermea-Mendoza JH (2024) Inflammatory Pseudotumor of the Liver Arising After Covid-19: A Case Report and Literature Review. Ann Case Report. 9: 2015. https://doi.org/10.29011/2574-7754.102015

Abstract

Inflammatory pseudotumors (IPTs) are rare tumors. We report the first case of a patient diagnosed with hepatic IPTs arising after coronavirus disease (COVID-19). A 50-year-old man presented with cough, dyspnea, and a positive COVID-19 test. Two weeks later, he developed dull pain in the right hypochondrium, fever, and jaundice. Computed tomography identified multiple hypo dense liver nodules. Biopsy reported an inflammatory fibrohistiocytic pseudotumor. The patient was treated with prednisone and azathioprine with complete regression. Hepatic IPTs (HIPTs) are rare, with an incidence of 1% within focal liver lesions; triggers include infections, foreign body response, or an immune system response. Clinical presentation ranges from asymptomatic to acutely ill with fever, jaundice, and even ascites. Histologic classification divides them into fibrohistiocytic and lymphoplasmacytic HIPTs. Treatment includes conservative management, surgical resection or medical management. Prognosis is generally good; nevertheless, multiple and aggressive HIPTs have been reported.

Keywords: Inflammatory Pseudotumor; Liver Pseudotumor; COVID-19; Coronavirus Disease.

Abbreviations: Ipts: Inflammatory Pseudotumors; HIPT: Hepatic Inflammatory Pseudotumor; COVID-19: Coronavirus Disease; PCR: Polymerase Chain Reaction; CT: Computed Tomography

Introduction

Inflammatory pseudotumors (IPTs) are rare tumors occurring mostly in the lung, with approximately 8% of extra pulmonary tumors located in the liver [1]. The histologic characteristics of hepatic inflammatory pseudotumors (HIPTs) include fibroblast or myofibroblast proliferation with inflammatory cell infiltration. Over the past decades, various names have been used to refer to these tumors, but in 2007, Nakanuma et al. [2] defined HIPTs into the most widely accepted histologic classification, dividing them into two groups: fibrohistiocytic HIPT and lymphoplasmacytic HIPT.

Numerous case reports of this entity have been published since it was first described by Pack and Baker in the lung in 1939 and in the liver in 1953 [3]. At present, more than 400 cases of HIPTs have been reported in the literature. Nevertheless, consensus on treatment is still lacking and different approaches are carried out according to limited physician experience.

We report the first case of a patient diagnosed with multiple HIPTs developing after coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Inform consent for this publication was provided by the patient.

Case Report

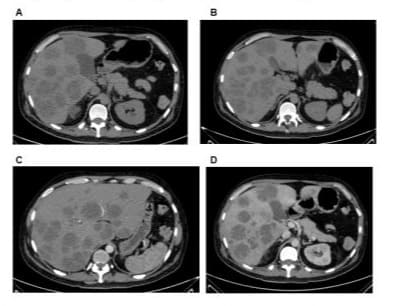

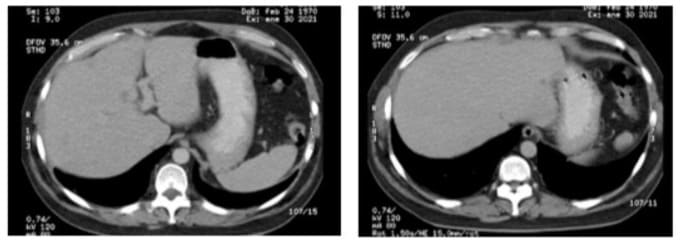

A 50-year-old man arrived at the emergency room in mid-July of 2020 with a history of physical exhaustion, cough, and dyspnea. His COVID-19 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test was positive. The patient required oxygen supplementation and was subsequently hospitalized. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest and abdomen was performed, revealing bilateral pneumonia associated with COVID-19 and no relevant features in the upper abdomen. The patient was managed with antibiotics, systemic steroids, and highflow oxygen, and given his subsequent clinical improvement, was discharged after 7 days. Two weeks after discharge, he developed dull pain in the right hypochondrium, fever, and jaundice. An ultra sonogram of the liver showed heterogeneous nodules in the right posterior lobe. Repeat CT scan revealed multiple hypo dense liver nodules, with no significant central enhancement in the arterial phase; some of the tumors had peripheral capsular enhancement with internal septa (Figures 1A-D). The patient was hospitalized with an initial diagnosis of liver abscesses and received broadspectrum intravenous antibiotics and supportive management. Laboratory results showed mildly elevated aminotransferase and total bilirubin levels, as well as neutrophilia. Ultrasoundguided fine-needle aspiration was performed; however, during the examination, the radiologist described solid nodules with areas of heterogeneity, and thus, liver metastases were suspected. The first pathology report showed only necrotic tissue. An open liver biopsy was subsequently performed. The first pathologist reviewing the case reported an inflammatory fibrohistiocytic pseudotumor.

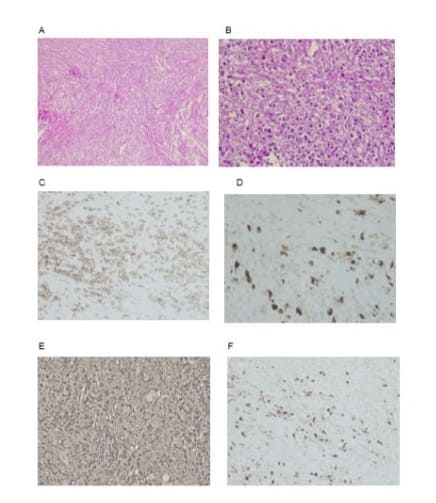

The patient came to our clinic for a second opinion, given that no specific treatment had been started 2 months after the last biopsy. Upon re-examination of the liver biopsy, we observed fibrous tissue in a storiform pattern, with abundant collagen, accompanied by numerous inflammatory cells with a predominance of plasma cells (Figures 2A-B) in the panoramic view. The findings were corroborated through cd138 immunohistochemical staining, in which the large quantity of plasma cells stood out (Figure 2C). Immunohistochemical staining for immunoglobulin G (IgG) showed cytoplasmic positivity in the plasma cells and that for IgG4 showed that 40% of the plasma cells were IgG4-producing cells (Figure 2D), with more than 10 plasma cells positive for IgG4 in each high-power field (Figures 2D-F). The diagnosis was thus revised to lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory pseudotumor.

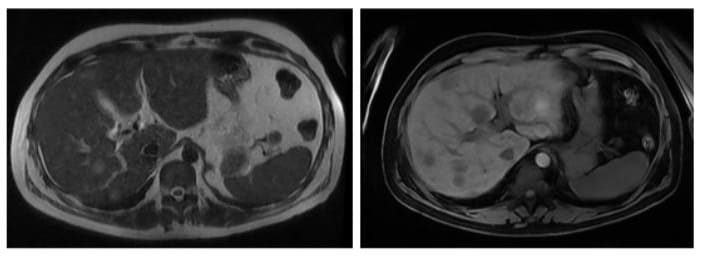

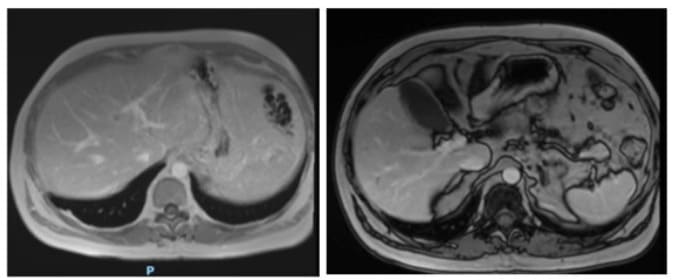

The pre-treatment work-up showed normal complete blood count, mild transaminitis, normal thyroid function, and mild IgG elevation on immunologic profile. He tested negative for hepatitis A, B, and C, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), cytomegalovirus, and herpes. Unfortunately, serum IgG4 was not initially taken. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) and contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen were also performed. The abdominal MRI, carried out 3 months after initial symptom presentation, showed multiple liver nodules, hyper intense on T2 and hypo intense on T1, with ring enhancement in the arterial phase (Figure 3). There was no evidence of extrahepatic or bile duct involvement.

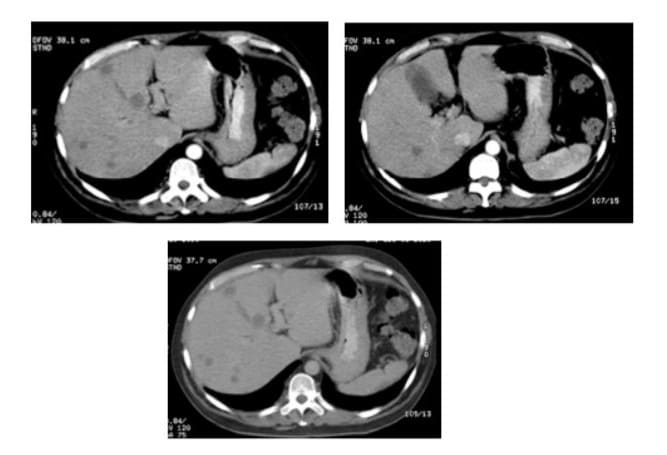

In November 2020, the patient was started on 40 mg of prednisone daily. One month later, a contrast-enhanced CT scan showed a decrease in the size of the liver nodules, with no abnormal contrast enhancement (Figure 4). His liver profile was normal, except for mildly elevated aminotransferases. Steroid tapering was started with a 10 mg reduction every week. Almost 12 weeks after treatment initiation, a follow-up CT scan (Figure 5) showed significant tumor reduction, with nodules measuring under 5 mm in segments III and IV. Azathioprine was then introduced at a dose of 50 mg/day and prednisone was maintained at a dose of 15 mg/day. The patient had good therapeutic tolerance. Aminotransferases returned to normal levels and he was clinically asymptomatic. Thereafter, the patient had irregular medical visits, resulting in slower-than-expected steroid tapering. By April 2021, he was on 12.5 mg of prednisone and 100 mg of azathioprine per day. A follow-up enhanced MRI was performed 7 months after immunosuppression initiation, showing residual nodular lesions under 3 mm in size in segments VI and VIII of the liver, with capsule-like enhancement in the delayed phase (Figure 6). Prednisone was tapered and azathioprine was increased to 150 mg/day (2 mg/kg). Three months after prednisone was withdrawn, a liver ultrasound was performed, with no nodules evident. A follow-up CT scan was scheduled 6 months after prednisone withdrawal, but the patient was lost to follow-up. On March 2024, the patient was readmitted to our unit, still on azathioprine at a dose of 50 mg/day and without prednisone. A CT scan was performed, showing no evidence of tumor, with normal liver tests, and thus, azathioprine was discontinued.

Figure 1: Images A and B show multiple hypo dense liver nodules. C) In the arterial phase, there is no significant enhancement. D) Peripheral enhancement of a fine capsule and internal septa is shown.

Figure 2: A) Photomicrograph with x100 magnification and hematoxylin and eosin staining that provides a panoramic view of the lesion, composed of fibrous tissue in a storiform pattern, with abundant collagen fibers, accompanied by numerous inflammatory cells. B) Photomicrograph with x400 magnification and hematoxylin and eosin staining providing a detailed view of the lesion components, the collagenized fibrous tissue, and inflammatory cells with a predominance of plasma cells.C) Photomicrograph with x100 magnification and cd138 immunohistochemical staining, in which the large quantity of positive cells corresponding to plasma cells stands out.D) Photomicrograph with x100 magnification and immunohistochemical staining for IgG4 showing that 40% of the plasma cells are IgG4producing cells.E) and F) Photomicrographs with x400 magnification and IgG4 immunohistochemical staining showing more than 10 plasma cells positive for IgG4 in each high-power field.

Figures 3A and 3B: Abdominal MRI showing multiple liver nodules that are hyper intense on T2 and hypo intense on T1, with ring enhancement after contrast material IV injection.

Figures 4A, 4B and 4C: Contrast enhanced CT scan of the abdomen showing a decrease in the size and number of the liver nodules, with no contrast enhancement, at one month after treatment.

Figures 5A and 5B: Follow-up CT scan obtained 12 weeks post-treatment, showing nodules smaller than 5 mm on segments III and IV.

Figures 6A and 6B: Post-contrast out-of-phase T1-weighted MRI images, showing residual nodular lesions towards segments VI and VIII of the liver smaller than 3 mm, with capsule-like enhancement in the delayed phase.

Discussion and Literature Review

HIPTs are rare tumors. A retrospective review of 403 patients that underwent liver resection for focal liver lesions demonstrated an incidence of 1% [4]. Various triggers have been identified, the majority of which are infectious in nature, but also include medications, foreign bodies, and an immune system response. The most accepted theory is that of an induced exaggerated inflammatory response to a harmful trigger that is perpetuated, and in turn, induces uncontrolled tumor-forming fibrosis. It is not thought to be a real tumor because cell proliferation is polyclonal in most cases, and thus, the term pseudotumor is used. Most HIPTs are benign, with recurrence of less than 5%, and almost all reported cases show no malignant potential [5,6]. Some sources consider HIPTs to be a group of lesions with a different nature and etiology [6,7]. which would explain their wide clinical activity, from regression to recurrence or metastasis. They comprise 4 main groups: 1) immune-mediated, associated with autoimmune diseases and with steroid response; [8-13] 2) infectious, associated with bacterial isolation, phlebitis, recurrent cholangitis, and biliary obstruction, with response to antibiotics; [14-18] 3) reparative in origin, after trauma, inflammation, hemorrhage, or foreign body response, with intense myofibroblastic proliferation and fibrosis; [19-21] and 4) neoplastic, with case reports of clonal proliferation, chromosomal abnormality, and malignant transformation [22,23].

Associations with viral infections due to hepatitis B, [24] hepatitis C, [25] HIV, [26] and Epstein-Barr virus, [27] as well as with gastrointestinal malignancy [28-30] and leukemia, [31,32] have likewise been reported.

Clinical Features

The clinical presentation of HIPTs ranges from asymptomatic to acute illness with fever, jaundice, and even ascites. Goldsmith et al. [33] published a review of 215 patients with HIPTs, reporting a mean age of 47 years and male predominance (60%). The most common symptoms were fever (49%), abdominal pain (48%), and fatigue/weight loss (37%); only 10% of the patients were asymptomatic. Other authors reported older mean ages (60-67 years), [2,34-36] with over one-third to half of the patients showing signs of systemic inflammatory response, such as leukocytosis and elevated values of C-reactive protein (CRP) or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) [33,34]. Majority of patients presented with a mild rise in transaminases and serum alkaline phosphatase, and over half of them had hyperbilirubinemia [36,37]. Meanwhile, serum tumor markers were normal in more than 90% of patients, [36,38] although CA 19-9 levels ranged from mild elevation in 2.2-11% [36-38] to over 1000 U/ml [39]. Alpha fetoprotein levels have been reported to be slightly elevated in 2.2%, [36,38,40] but also as high as over 800 U/ml [40]. The most common presentation is a solitary mass in more than 80% of cases, although multiple tumors have been observed, as well [34,36,41,42].

Imaging Features

No specific radiologic findings are associated with HIPT. Most of the reported cases are detected as solitary or multiple nodular lesions on imaging studies. Despite non-specific radiologic appearances, various imaging modalities can offer valuable clues in making the diagnosis [43,44]. On ultrasonography, lesions may appear hyperechoic or hypoechoic, with septations and increased through transmission, with or without a mosaic pattern, and with ill-defined or well-circumscribed margins [43,45].

On CT, lesions are hypo dense in relation to the liver parenchyma on plain images. Contrast-enhanced CT imaging demonstrates various enhancement patterns according to the vascularity of the tumor, such as peripheral enhancement with delayed central filling, homogeneous or heterogeneous enhancement, and septum enhancement. Alternatively, there may be negative enhancement or central necrosis. CT tends to show varying degrees of enhancement in the portal phase, with increased enhancement in the late stages, which can help differentiate the lesion from a malignant tumor [44,46,47].

On MRI, liver lesions are hypo intense on T1-weighted images and hyper intense on T2-weighted images. With intravenous contrast, peripheral enhancement on delayed-phase images and increasing enhancement of central areas with diffusion restriction are observed. Peripheral enhancement is thought to be related to the slow washout of contrast material in inflamed fibrous tissue [44,48].

Generalized lymphadenopathies and Porto mesenteric thrombosis have been reported by some authors [17,39,49] with case reports of the development of portal hypertension, Budd-Chiari syndrome, and ascites [50,51].

Needle biopsy may be helpful in providing a correct diagnosis, although some authors suggest fine-needle aspiration should be avoided, as the procedure leads to a high incidence of misdiagnosis [52,53]. Because of the lack of specific clinical, laboratory, or even radiologic features, clinical suspicion is crucial and histopathologic study mandatory. The majority of cases are initially diagnosed as malignant tumors, mainly hepatocarcinoma or cholangiocarcinoma, or as liver abscess [24,25,35,36,43,45].

HIPT is a rare disease whose histologic hallmarks are chronic inflammatory cells and fibrosis [34]. Some tumors previously classified as variants of HIPT have been reclassified as different entities, such as inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor and follicular dendritic cell type inflammatory pseudotumor [54]. Recently, 2 types of HIPT have been described: fibrohistiocytic HIPT and lymphoplasmacytic HIPT. The major histologic features of lymphoplasmacytic HIPT include dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, spiral fibrosis (at least focally), and obliterative phlebitis. Other histologic features include phlebitis with no vascular obliteration and eosinophilic infiltration; however, these are neither specific nor sensitive for diagnosis if they are not associated with the major features. The presence of 2 out of 3 major features is required to make the diagnosis. The presence of more than 10 IgG4-positive plasmacytic cells per high-power field increases the diagnostic certainty, as does more than 40% IgG4-positive and IgG-positive cells [2].

Treatment

Due to diagnostic difficulty and the different phenotypes, some patients undergo surgical resection, whereas others are managed with antibiotics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, immunosuppressants, or no medications. In one of the largest reviews on HIPT involving 188 cases, [33] 40% had liver resection, almost half of the medically-treated patients received antibiotics, one-third had no treatment, and 15% were treated with steroids. The rationale for using antibiotics is their association with biliary disease and cholangitis, as well as the reported positive bacterial cultures [14-18,36]. Most of the earlier literature advocated for surgical treatment, [36,38] and in many reports, surgery was both a diagnostic and therapeutic approach. More recently, surgical resection has been mostly reserved for patients with diagnostic uncertainty, lack of response to conservative therapy, severe symptoms, elevation of tumor markers, or increased tumor size, given that malignancy is difficult to rule out [55].

Different immunosuppression regimens have been used. Most include steroids, either oral prednisone with doses ranging from 30 to 100 mg/d [41,49,56,57] or intravenous methylprednisolone administered at 1 g/day in 3-day pulses, [58] tapering over 3 to 6 months. Other authors have used azathioprine, [56] budesonide, [56] and cyclosporine [49]. Treatment with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, either in the short-term [59] or up to 2 years, [60] have also been reported, with and without complete response.

Regression rates with conservative options have been reported at 90% or higher [5]. When comparing outcomes between patients who underwent liver resection and those who received medical management, with an average follow-up of 31 months, surgical treatment resulted in good outcomes in 61%, with a 9.7% rate of major complications (sepsis, acute renal failure, myocardial infarction, portal vein stenosis, bile leak, deep venous thrombosis, and hepatic artery thrombosis) and 5.6% mortality [33]. Meanwhile, medical treated resulted in good outcomes in 87%, with a 7.2% mortality rate. No statistically significant difference in mortality rates was observed between the groups.

Finally, several reports of spontaneous resolution of HIPTs [6164] have also been published, with a mean time of 6 months, albeit regression was not complete in all cases. Reports on liver transplantation have mainly been conducted on children with obstructive jaundice and portal hypertension or with extensive involvement [65,66].

Prognosis

The prognosis of HIPTs is generally good, with either conservative or surgical treatment modalities. Nevertheless, multiple and aggressive HIPTs, recurrences, invasion of adjacent structures, and even metastases have been reported [23,48,67,68].

Importantly, most of the cases reporting malignant transformation or metastases were referred to as myofibroblastic lesions and were published prior to the current histopathologic HIPT classification; thus, they were most likely a different type of tumor, now known as inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor.

Our patient presented with signs and symptoms of an inflammatory response, with initial imaging features suggestive of liver abscesses, consistent with the initial diagnosis of most HIPTs as either malignant tumors or abscesses. Our patient was finally classified as having lymphoplasmacytic HIPT, and COVID-19 was clearly identified as the trigger. We speculate that a hyper immune reaction was mediated by the coronavirus infection, leading to an activation of immune cells in the liver and resulting in the development of the HIPT. Moreover, he did not respond to broadspectrum antibiotics, but responded well to immunosuppression, despite the high disease burden, achieving complete regression. We found two main differences in the classical presentation of lymphoplasmacytic HIPT in our patient. First, Zen et al. [2] reported that lymphoplasmacytic HIPTs are mainly solitary and hilar lesions, similar to periductal infiltrating-type cholangiocarcinoma, showing minimal or no systemic inflammation, which was unlike the presentation in our patient. Second, most cases are solitary masses with some reports of multiple tumors, but extensive disease encompassing all of the liver is rarely seen [34,36,41,42]. No clinical or radiologic features to correctly diagnose HIPT with non-invasive tools are currently available, making the sampling of tumor tissue mandatory. We believe that correct histopathologic HIPT classification, determined through unified criteria, will enable proper identification of the type of HIPT and guide the best therapeutic approach for each patient. To the best of our knowledge, the case presented herein is the first of an HIPT arising after COVID-19.

Funding: No funding was received.

Conflict of interest: None of the authors have conflicts of interest.

Author contributions: Dr. Alma Kuljacha-Gastélum conceptualization, data curation, supervision and writing of the manuscript. Dr. Eduardo González-Murillo writing the manuscript and investigation regarding histopathological findings, elaborated microphotography figures and description of pathology.Dr. Héctor Bermea-Fuentes writing the manuscript and literature investigation regarding imaging findings and elaborated image figures and descriptions.

References

- Coffin CM, Humphrey PA, Dehner LP. (1988) Extrapulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: a clinical and pathological survey. Semin Diagn Pathol 15: 85-101.

- Zen Y, Fujii T, Sato Y, Masuda S, Nakanuma Y (2007) Pathological classification of hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor with respect to IgG4-related disease. Mod Pathol 20: 884-94.

- Pack GT, Baker HW. (1953) Total right hepatic lobectomy; report of a case. Ann Surg 138: 253–8.

- Torzilli G, Inoue K, Midorikawa Y, Hui AM, Takayama T, Makuuchi M. (2001) Inflammatory pseudotumours of the liver: prevalence and clinical impact in surgical patients. Hepatogastroenterology 48: 11181123.

- Belghiti J, Cauchy F, Paradis V, Vilagrain V. (2014) Diagnosis and management of solid benign liver lesions. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 11: 736-749.

- Chan JK. (1996) Inflammatory pseudotumor: a family of lesions of diverse nature and etiologies. Adv Anat Path. 3: 156-171.

- Cohen M, Huminer D, Salamon F, Cohen M, Tur-Kaspla R. (2005) Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver: a therapeutic dilemma. Isr Med Assoc J 7: 472-473.

- Papachristou GI, Wu T, Marsh W, Plevy SE. (2004) Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver associated with Crohn’s disease. J Clin Gastroenterol 38: 818-822.

- Hosokawa A, Takahashi H, Akaike J, Okuda H, Murakami R, et al. (1998) A case of Sjögren’s syndrome associated with inflammatory pseudotumour of the liver. Nihon Rinsho Meneki Gakkai Kaishi 21: 226-233.

- Díaz-Torné C, Narváez J, Lama ED, Diez-García M, Narváez JA, et al. (2007) Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 57: 1102-1106.

- Hirano K, Shiratori Y, Komatsu Y, Yamamoto N, Sasahira N, et al. (2003) Involvement of the biliary system in autoimmune pancreatitis: A follow up study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 1: 453-564.

- Rai T, Ohira H, Tojo J, Takihuchi J, Shishido S, et al. (2003) A case of hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor with primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatol Res 26: 249-253.

- Naitoh I, Nakazawa T, Ohara H, Ando T, Hayashi K, et al. (2009) IgG4related hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor with sclerosing cholangitis: a case report and review of the literature. Cases J 2: 7029.

- Tsou Y, Lin CJ, Lui N, Lin C, Lin C, Lin SM. (2007) Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver: report of eight cases, including three unusual cases, and a literature review. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 22:2143-2147.

- Faraj W, Ajouz H, Mukherji D, Kealy G, Shamseddine A, et al (2011) Inflammatory pseudo-tumor of the liver: a rare pathological entity. World J Surg Oncol 23: 9-5.

- Nakanuma Y, Tsuneyama K, Masuda S, Tomioka T. (1994) Hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor associated with chronic cholangitis: report of three cases. Hum Pathol 25: 86-91.

- Someren A. (1978) “Inflammatory pseudotumor” of liver with occlusive phlebitis: report of a case in a child and review of the literature. Am J Clin Pathol 69:176-81.

- Yoon KH, Ha HK, Lee JS, Suh JH, Kim MH, Kim P, et al. (1999) Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver in patients with recurrent pyogenic cholangitis: CT-histopathologic correlation. Radiol 211: 3639.

- Hayashi M, Fujita M, Abe K, Takahashi A, Muto M, et al. (2021) Intratumor Abscess in a Posttraumatic Hepatic Inflammatory Pseudotumor Spreading Out of the Liver. Intern Med 60: 235-240.

- Srinivasan UP, Duraisamy AB, Llango S, Rathinasamy A, Chandramohan SM. (2013) Inflammatory pseudotumor of liver secondary to migrated fishbone - a rare cause with an unusual presentation. Ann Gastroenterol 26: 84-86.

- Del Fabbro D, Torzilli G, Gambetti A, Leoni P, Gendarini A, Olivari N. (2004) Liver inflammatory pseudotumor due to an intrahepatic wooden toothpick. J Hepatol 40: 498.

- Biselli R, Ferlini C, Fattorossi A, Boldrini R, Bosman C. (1996) Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (inflammatory pseudotumor): DNA flow cytometric analysis of nine pediatric cases. Cancer 77: 778–784.

- Pecorella I, Ciardi A, Memeo L, Trombetta G, De Quarto A, et al. (1999) Inflammatory pseudotumour of the liver--evidence for malignant transformation. Pathol Res Pract 195: 115-20.

- Yin L, Zhu B, Lu XY, Lau WY, Zhang YJ. (2017) Misdiagnosing hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor as hepatocellular carcinoma: A case report. J Glob Health 1:76-78.

- Kim SR, Hayashi Y, Kudo M, Matsuoka T, Imoto S, Sasaki K, et al. (1999) Inflammatory pseudotumor of the live in a patient with chronic hepatitis C: difficulty in differentiating it from hepatocellular carcinoma. Pathol Int 49: 726-730.

- Tai YS, Lin PW, Chen SG, Chang KC. (1998) Inflammatory pseudotumour of the liver in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus infection, Hepatogastroenterology 45: 1760-1763.

- You Y, Shao H, Bui K, Klapman J, Cui Q, Coppola D. (2014) EpsteinBarr Virus Positive Inflammatory Pseudotumor of the Liver: Report of a Challenging Case and Review of the Literature. Ann Clin Lab Sci 44: 489-498.

- Nishimura R, Teramoto N, Tanada M, Kurira A, Mogami H. (2005) Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver associated with malignant disease: report of two cases and a review of the literature. Virchows Arch 447: 660-664.

- Lo OS, Poon RT, Lam CM, Fan ST. (2004) Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver in association with a gastrointestinal stromal tumor: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 10: 1840-1843.

- Nitta T, Kataoka J, Inoue Y, Fujii K, Ohta M, Kawasaki H, et al. (2017) A case of multiple inflammatory hepatic pseudotumor protruding from the liver surface after colonic cancer. Int J Surg Case Rep 36: 261–264.

- Isobe H, Nishi Y, Fukutomi T, Iwamoto H, Nakamuta M,et al. (1991) Inflammatory pseudotumour of the liver associated with acute myelomonocytic leukemia. Am J Gastroenterol 86: 238-240.

- Qin Zheng R, Kudo M. (2003) Hepatobiliary and pancreatic: Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 18: 994.

- Goldsmith PJ, Loganathan A, Jacob M, Ahmad N, Toogood GJ, et al (2009) Inflammatory pseudotumours of the liver: a spectrum of presentation and management options. Eur J Surg Oncol 35: 12951298.

- Oh K, Hwang S, Ahn CS, Kim KH, Moon DB, Ha TY, et al. (2021) Clinicopathological features and post-resection outcomes of inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver. Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 25: 34-38.

- Ahn KS, Kang KJ, Kim YH, Lim TJ, Jung HR, et al. (2012) Inflammatory pseudotumors mimicking intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma of the liver; IgG4-positivity and its clinical significance. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 19: 405-412.

- Park JY, Choi MS, Lim YS, Park JW, Kim SU, et al. (2014) Clinical features, image findings, and prognosis of inflammatory pseudotumour of the liver: a multicenter experience of 45 cases. Gut Liver 8: 58–63.

- Nigam N, Rajani SS, Rastogi A, Patil A, Agrawal N, et al. (2019) Inflammatory pseudotumors of the liver: Importance of a multimodal approach with the insistance of needle biopsy. J Lab Physicians 11: 361-368.

- Yang X, Zhu J, Biskup E, Cai F, Li A. Inflammatory pseudotumors of the liver: experience of 114 cases. Tumor Biol 36: 5143-5148.

- Ogawa T, Yokoi H, Kawarada Y. (1998) A case of Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver causing elevated serum CA 19-9 levels. Am J of Gastroenterol 93:2551-2555.

- Maruno M, Imai K, Nakao Y, Kitano Y, Kaida T, et al. (2021) Multiple hepatic inflammatory pseudotumors with elevated alpha-fetoprotein and alpha-fetoprotein lectin 3 fraction with various PET accumulations: a case report. Surg Case Rep 7: 107.

- Gesualdo A, Tamburrano R, Gentile A, Giannini A, Palasciano T, et al (2017) A diagnosis of pseudotumor of the liver by contrast enhanced ultrasound and fine-needle biopsy: a case report. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med 4.

- Oh K, Hwang S, Ahn CS, Kim KH, Moon DB, et al. (2021) Clinicopathological features and post-resection outcomes of inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver. Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 25: 34-38.

- Inaba K, Suzuki S, Yokpi Y, Ota S, Nakamura T, et al. (2003) Hepatic Inflammatory Pseudotumor Mimicking Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma: Report of a Case. Surg Today 33: 717-717.

- Zheng R, Kudo M. (2003) Hepatobiliary and pancreatic: Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver. J of Gastroenterol and Hepatol 18: 994.

- Yoon J, Hyun J, Yeob T, Kyoung W, Kim J, Yeon J. (2012) Hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor misinterpreted as hepatocellular carcinoma. Clinical and Molecular Hepatology 128: 239-244.

- Toda K, Yasuda I, Nishigaki Y, Enya M, Yamada T, et al. (2000) Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver with primary sclerosing cholangitis.J Gastroenterol 35: 304-309.

- Al-Hussaini H, Azouz H, Abu-Zaid A. (2015) Hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor presenting in an 8-year-old boy: A case report and review if the literature. World J Gastroenterol 21: 8730-8738.

- Nigam N, Singh S, Rastogi A, Patil A, Agrawai N, et al (2019) Inflammatory pseudotumors of the liver: Importance of a multimodal approach with the insistence of needle biopsy. J Lab Physicians 11: 361-368.

- Nishimaki T, Matsuzaki H, Sato Y, Kondo Y, Kasukawa R. (1992) Cyclosporin for Inflammatory Pseudotumor. Intern Med 31: 404-406.

- Jain A, Gupta N, Bharti P. (2014) An Unusual Association of Inflammatory Pseudotumor of the Liver and Dorsal Pancreatic Agenesis Presenting as Reversible Portal Hypertension: A Case Report. J Clin Diagn Res 8: MD08-MD10.

- Ramírez P. (2013) Budd-Chiari syndrome secondary to inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver: Report of a case with a 10-year follow-up. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 105: 360-362.

- Fukuya T, Honda H, Matsumata T, Kawanami T, Shimoda Y, et al (1994) Diagnosis of inflammatory pseudotumour of the liver: value of CT.Am J Roentgenol 163: 1087-1091.

- Locke J, Choti M, Torbenson M, Horton K, Molmenti E. (2005) Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 12: 314-316.

- Rosa B, Moutinho-Ribeiro P, Pereira JM, Fonseca D, Lopes J, et al. (2012) Ghost Tumor: An Inflammatory Pseudotumor of the Liver. Gastroenterol Hepatol 212;8: 633-634.

- Zhang Y, Lu H, Ji H, Li Y. (2015) Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver: A case report and literature review. Intractable Rare Dis Res 4: 155-158.

- Karlas T, Mossner J, Keim V. (2013) A 44-year-old patient with fever, night sweats, and arthralgia. Gastroenterol 144: e1-e3.

- Shibata M, Matsubayashi H, Aramaki T, Uesaka K, Tsutsumi N, et al. (2016) A case of IgG4-related hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor replaced by an abscess after steroid treatment. BMC Gastroenterol 16: 89.

- Kawaguchi T, Mochizuki K, Kizu, T, Miyazaki M, Yakushijin T, et al. (2005) Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver and spleen diagnosed by percutaneous needle biopsy. World J Gastroenterol 18: 90-95.

- Vassiladis T, Vougiouklis N, Patsiaoura K, Mpoumponaris A, Nikolaidis N, et al. (2007) Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver successfully treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: A challenge diagnosis for one not so rare entity.Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 19: 1016-1020.

- Lameirao C, Silva N, Pressa J. (2019) Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver: clinical case. J Gastroenterol 26: 305-307.

- Jerraya H, Jarboui S, Daghmoura H, Zaouche A. (2011) A new case of spontaneous regression of inflammatory hepatic pseudotumor. Case Rep Med 1: 139125.

- Patel H, Nanavati S, Ha J, Shah A, Baddoura W. (2018) Spontaneous Resolution of IgG4-Related Hepatic Inflammatory Pseudotumor Mimicking Malignancy. Case Rep Gastroenterol 12: 311-316.

- Mulki R, Garg S, Manatsathit W, Miick R. (2015) IgG4-related inflammatory pseudotumour mimicking a hepatic abscess impending rupture. BMJ Case Rep 2015: bcr2015211893.

- Yamaguchi J, Sakamoto Y, Sano T, Shimada K, Kosuge T. (2007) Spontaneous regression of inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver: report of three cases. Surg Today 37: 525-529.

- Heneghan MA, Kaplan CG, Priebe CJ, Partin JS. (1984) Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver: a rare cause of obstructive jaundice and portal hypertension in a child. Pediatr Radiol 14: 433-435.

- Kim HB, Maller E, Redd D, Hebra A, Davidoff A, Buzby M, et al. (1996) Orthotopic liver transplantation for inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the liver hilium. J Pediatr Surg 31: 840-842.

- Walsh SV, Evangelista F, Khettry U. (1998) Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the pancreaticobiliary region: Morphologic and immunocytochemical study of three cases. Am J Surg Pathol 22: 412-418.

- Chang SD, Scali EP, Abrahams Z, Tha S, Yoshida EM. (2014) Inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver: a rare case of recurrence following surgical resection. J Radiol Case Rep 8: 23-30.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.