Incidental Disappearing Proficient Mis-Match Repair Colon Cancer in a Patient with Advanced Metastatic Melanoma and the Rare Complications of Immunotherapy

by Jonathan Hew1,3*, Ali Mohtashami1, Bree Rebolledo1, Alexander M. Menzies2,3,4, Beryl Lin3,5, Venessa HM Tsang5, Yasser Salama1

1Department of Colorectal Surgery, Royal North Shore Hospital, NSW, Australia

2Melanoma Institute Australia, The University of Sydney, Australia

3Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, Australia

4Royal North Shore and Mater Hospitals, NSW, Australia

5Department of Endocrinology, Royal North Shore Hospital, NSW, Australia

*Corresponding author: Dr Jonathan Hew, Department of Colorectal Surgery, University of Sydney, Royal North Shore Hospital, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Received Date: 4 December 2024

Accepted Date: 09 December 2024

Published Date: 11 December 2024

Citation: Hew J, Mohtashami A, Rebolledo B, Menzies AM, Lin B, et al. (2024) Incidental Disappearing Proficient Mis-Match Repair Colon Cancer in a Patient with Advanced Metastatic Melanoma and the Rare Complications of Immunotherapy. Ann Case Report. 9: 2111. https://doi.org/10.29011/2574-7754.102111

Abstract

Complete pathological response (cPR) to immunotherapy of proficient in mismatch repair (pMMR) colorectal cancer is a rare event. Here we present and discuss a case of an incidental pMMR colon cancer which had a cPR to combination immunotherapy given for the treatment of metastatic melanoma. Whilst the patient had a cPR to immunotherapy, his clinical course was complicated by secondary adrenal insufficiency from immunotherapy-related hypophysitis. This case highlights a number of emerging topics in immunotherapy and colorectal cancer, specifically the treatment and selection of pMMR tumours with immunotherapy and the balance of risk when managing oncological outcomes, side effects or immunotherapy and surgical complications.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer; Immunotherapy; Mismatch repair; Immune related adverse events

Introduction

Immunotherapy is emerging as a first line treatment for deficient in mismatch repair (dMMR) colorectal cancer and is a well-established treatment for metastatic melanoma [1–4]. In the recent NICHE-2 trial, neo-adjuvant combination immunotherapy using ipilimumab (CTLA-4 inhibitor) and nivolumab (PDL-1inhibitor) for locally advanced dMMR colon cancer was shown to be extremely effective with 68% of patients having a complete pathological response (cPR) meaning 0% of tumour remaining. The treatment was well tolerated with a low incidence of severe immune related adverse events (irAEs) with 4% experiencing grade 3 and 4 toxicity [2]. In the NICHE-1 trial in proficient mismatch repair (pMMR) tumours up to 13% of patients had a cPR to immunotherapy [5,6]. Clinical efficacy is much improved in dMMR tumours due to the high tumour mutational burden leading to a prolific expression of immunogenic tumour neoantigens. This is not the case in pMMR tumours. The mechanism of response to immunotherapy in pMMR tumours is an area of active research with a better response seen in patients with a high tumour infiltrating T-cells [7,8].

Whilst a promising and powerful therapy, irAEs are common particularly with combination immunotherapy and can affect any organ system [9]. The incidence of any irAEs in trials using combination therapy is up to 95% with grade III and IV events occurring in up to 24% of patients [10]. Common irAEs include cutaneous, intestinal and hepatic conditions [11].With combination immunotherapy, endocrinopathies have been reported in up to 37% of patients, with 12-13% developing hypophysitis with a proportion of these progressing to secondary adrenal insufficiency [12,13]. Other rare but potentially fatal complications include pneumonitis (10% fatality) and myocarditis (50% fatality) [14].

We report on a case of a patient with an incidental pMMR colorectal cancer who had a cPR to combination immunotherapy given for metastatic melanoma. The patient’s clinical course was complicated by multiple post-operative episodes of adrenal crisis in the context of secondary adrenal insufficiency from immunotherapy-related hypophysitis. He also suffered from immune therapy related diarrhoea. This case highlights the remarkable and promising effect of immunotherapy but also the consequences and complexities of managing these potentially high-risk surgical patients and the permanent side effects of immunotherapy.

Case Presentation

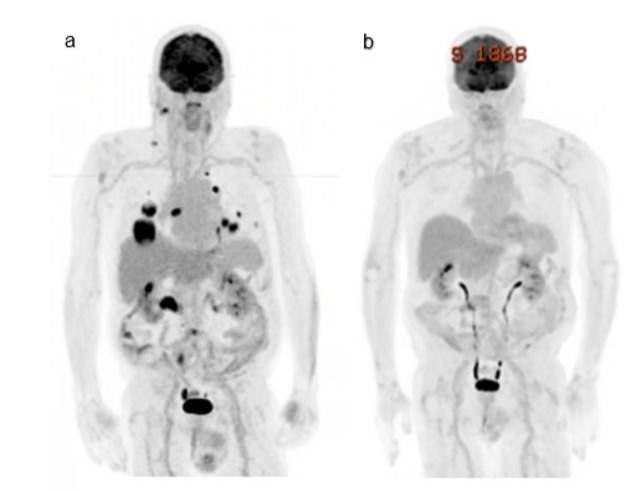

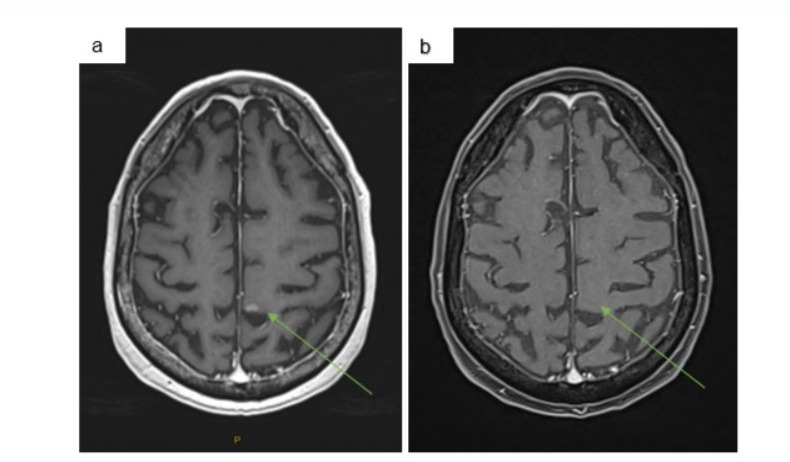

A 75 year old male presented with a prior history of cutaneous melanoma and a mass over the right mastoid process in October 2023, which confirmed recurrent melanoma on excisional biopsy. He had a background of a seizure disorder of unknown aetiology managed with levetiracetam, hypertension, ischemic heart disease and hypercholesteremia. Staging with a CT PET showed metastases to right cervical lymph nodes, multiple pulmonary nodules and an FDG avid mass in the proximal transverse colon (Figure 1a). An MRI brain showed a single 6mm intra-cerebral paracentral metastasis (Figure 2a).

Figure 1: a) Staging FDG CT PET December 2023 showing metastasis right cervical lymph nodes, lung and mass in proximal transverse colon. b) Progress CT PET in March 2024 after 3 cycles of combination immunotherapy showing a complete pathological response.

Figure 2: a) Staging MRI brain December 2023 showing single left parafalcine metastasis. b) MRI brain February 2024 after 3 cycles of combination immunotherapy showing a complete pathological response.

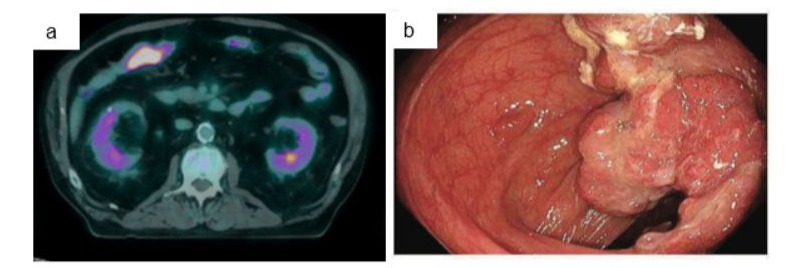

He received 3 cycles of combination immunotherapy including Ipilimumab 3mg/kg and Nivolumab1mg/kg from January with a complete response on PET scan and MRI brain (Figure 1b and 2b). After his first dose of immunotherapy, he had a colonoscopy which found a large, ulcerated, non-circumferential, partially obstructing mass in the proximal transverse colon (Figure 3a). Biopsy results proved a synchronous colonic adenocarcinoma which was pMMR with retained staining for MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2. After the third cycle of immunotherapy, he was admitted with confusion, fever, headaches and watery diarrhoea. He was treated with broad spectrum antibiotics, high-dose prednisone for suspected secondary adrenal insufficiency due to immunotherapy-related hypophysitis and loperamide for immunotherapy-related diarrhoea. Although secondary adrenal insufficiency was not biochemically confirmed at this time, he had no evidence of any other endocrinopathies. High-dose prednisone was weaned over 6 weeks to 5mg daily for glucocorticoid replacement. Diarrhoea resolved with loperamide.

Figure 3: a) Staging FDG PET December 2023 showing FDG avid mass in proximal right colon. b) Endoscopy in January 2024 showing transverse colonic adenocarcinoma.

In late March 2024 he underwent a standard laparoscopic right hemicolectomy and initially progressed well despite an ileus. Pathological assessment of the operative specimen demonstrated a 20mm area of residual fibrosis confirming a pathological complete response (pCR). On post-operative day 5, he developed florid septic shock with multi-organ failure with fever, tachycardia, a severe metabolic acidosis, respiratory and renal failure. As the patient was in extremis requiring high doses of vasopressor support, he was taken directly for an exploratory laparotomy which found no evidence of anastomotic leak. An area of erythema over the left flank was debrided at the time due to concern of necrotising fasciitis this subsequently returned with no evidence of necrotising fasciitis on histopathology. He was supported in ICU with broad spectrum antibiotics, fluids, total parenteral nutrition and stress dosing of hydrocortisone. A progress CT again did not demonstrate anastomotic leak but did demonstrate a small mesenteric haematoma. He progressed well in ICU with weaning of multiorgan support, corticosteroid dosing and was discharged from ICU in early April.

A few days later he rapidly deteriorated on the ward requiring readmission to ICU with multifactorial respiratory failure from a combination of suspected aspiration and hospital acquired pneumonia. Sputum cultures eventually grew candida parapsilosis with a CT chest showing left basal inflammatory changes with pleural effusions. He was again discharged to the ward after 4 days of ICU support including high flow nasal oxygen, intravenous stress dosing of corticosteroids, broad spectrum antibiotics and aggressive diuresis.

In mid-April, he developed high fevers and a fungaemia culturing candida paraspilosis from multiple peripheral cultures the source being considered chest or the intra-abdominal haematoma demonstrated on the previous CT abdomen. He was managed with IV anidulafungin and transitioned to oral fluconazole. Throughout the admission he continued to have intermittent low volume diarrhoea which responded to loperamide and was maintained on prednisone for presumed immune related hypophysitis. He was discharged home at the end of April.

He was readmitted 4 days later after collapsing at home with large volume diarrhoea, fever, hypotension, a severe metabolic acidosis, rhabdomyolysis and an acute kidney injury. Precipitating this presentation was period of severe diarrhoea which, in combination with poor oral intake led to a combined hypovolaemic and septic shock. He responded well to fluid resuscitation, stress dosing of corticosteroids, empiric broad spectrum antibiotics and intravenous potassium replacement. Diarrhoea was managed with escalating doses of loperamide, stool samples were again culture negative as was clostridium difficile ELISA. He was discharged from ICU and unfortunately on the ward acquired a COVID infection requiring ward level nasal oxygen support and remdesivir. He underwent a colonoscopy to determine if there was macroscopic evidence of immunotherapy-related colitis. The mucosa was grossly normal and no biopsy was taken. He was discharged to rehabilitation then transitioned to home. In clinic, a repeat pituitary screen confirmed secondary adrenal insufficiency from immunotherapy-related hypophysitis with an undetectable cortisol and ACTH without evidence of any other endocrinopathies.

Discussion

This case highlights a number of current evolving areas in immunotherapy and colorectal cancer. It is extremely rare for a pMMR colon cancer to have a complete pathological response to immunotherapy. To date, only two other cases have been recorded in the literature where 2/15 patients in the pMMR group in the NICHE-1 trial had a complete pathological response to ipilimumab and nivolumab [5,6]. Whilst response rates are low with pMMR colon cancer, current research efforts are focused on discovering systemic regimens which combine conventional and experimental treatments with immunotherapy to enhance the immunogenicity of these tumours.

Conventional treatments trialled in a metastatic colorectal cancer include combining immunotherapy with chemotherapy, based on the hypothesis that cytotoxic therapy induced cell death is likely to release vast numbers of tumour antigens increasing T-cell response [15-18]. Other agents used include anti-epidermal growth factor receptor antibodies (EGFR) which similarly increase immunogenic cell death and promote T-cell influx. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGF) inhibition blocks the immunosuppressive effects of VEGFR and reduces the immunosuppressive cell population in the tumour micro-environment [15]. Immune evasion is facilitated by BRAF mutations; hence, anti-BRAF V600e targeting agents combined with immunotherapy are another avenue for enhancing immunotherapy [8,19]. Novel immune to tumour cell pathways are also being explored such as lymphocyte activating gene 3 (LAG3) inhibitor receptor on T-cells [20,21]. Overall, in the metastatic setting only marginal improvement in oncological outcomes have been achieved to date.

The response rate of localised pMMR tumours to immunotherapy may be greater than in metastatic disease. Our patient had an incidental complete pathological response with no evidence of systemic colorectal cancer at the time of diagnosis. Similarly, the two pMMR patients in the NICHE-1 trial were localised T2 and T3 tumours [5]. This is encouraging as it suggests there are a subset of pMMR tumours that can achieve a complete pathological response to immunotherapy alone without the need for combination cytotoxic therapy. Current research is aimed at identifying tumour biological and genetic characteristics which predict response to immunotherapy in pMMR cancers. Active areas of research include determining susceptibility genetic profiling matching response to immunotherapy with mutations in bRAF, VEGF, APC, POLE and POLD1 mutations [7,8]. Biomarkers for predicting response to immunotherapy in pMMR patients is also an expanding field with research exploring the efficacy of absolute T-cell count, tumour mutational burden, CPS score and novel biomarkers such as sPDL-1 [22,23]. Consideration is also being given to the influence of the microbiome on response to immunotherapy [21,24].

Selection of patients who may have a cPR when treated with combination immunotherapy in pMMR tumours is imperative. Overtreatment of patients who will not respond to immunotherapy exposures patients to potentially life threatening and permanent irAEs [9,10]. Our patient suffered from immunotherapy-related diarrhoea and hypophysitis with secondary adrenal insufficiency, a rare but serious irAE which left him susceptible to adrenal crisis and systemic collapse in the context of infection post-operatively. The source of infection was largely indeterminant from the initial ICU admission; the second was likely a fungal hospital acquired pneumonia with fungaemia; and the third episode, characterized by severe diarrhoea, was also unknown and may have represented a severe flare of immune related diarrhoea or colitis, although no evidence of colitis was found on endoscopy. This case highlights the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for adrenal insufficiency in patients who have had immunotherapy.

Conclusion

Identifying patients who have favorable pMMR early tumours which may respond to treatment with immunotherapy and achieve a cPR is imperative. In future these patients may be suitable for a watch and wait pathway as is the case for rectal cancer with a cPR to total neo-adjuvant therapy. The selection of a treatment pathway in the era of effective immunotherapy requires a delicate balance of the risk of immunotherapy related side effects, oncological outcomes and the complications of surgery.

Acknowledgments

Nil

Ethical considerations

Written consent obtained from patient for publication

Conflict of interest

No disclosures

References

- Loria A, Ammann AM, Olowokure OO, Paquette IM, Justiniano CF. (2024). Systematic Review of Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy for Mismatch Repair Deficient Locally Advanced Colon Cancer: An Emerging Strategy. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 67: 762-771.

- Chalabi M, Verschoor YL, Tan PB, Balduzzi S, Van Lent AU, et al. (2024). Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy in Locally Advanced Mismatch Repair–Deficient Colon Cancer. N Engl J Med. 390: 1949-1958.

- Cercek A, Lumish M, Sinopoli J, Weiss J, Shia J, et al. (2022). PD-1 Blockade in Mismatch Repair–Deficient, Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer. N Engl J Med. 386: 2363-2376.

- Benhima N, Belbaraka R, Langouo Fontsa MD. (2024). Single agent vs combination immunotherapy in advanced melanoma: a review of the evidence. Current Opinion in Oncology. 36: 69-73.

- Chalabi M, Fanchi LF, Dijkstra KK, Van Den Berg JG, Aalbers AG, et al. (2020). Neoadjuvant immunotherapy leads to pathological responses in MMR-proficient and MMR-deficient early-stage colon cancers. Nat Med. 26: 566-576.

- Zhou L, Yang XQ, Zhao G yue, Wang F jian, Liu X. (2023). Meta-analysis of neoadjuvant immunotherapy for non-metastatic colorectal cancer. Front Immunol. 14: 1044353.

- Takei S, Tanaka Y, Lin YT, Koyama S, Fukuoka S, et al. (2024). Multiomic molecular characterization of the response to combination immunotherapy in MSS/pMMR metastatic colorectal cancer. J Immunother Cancer. 12: e008210.

- El Hajj J, Reddy S, Verma N, Huang EH, Kazmi SM. (2023). Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in pMMR/MSS Colorectal Cancer. J Gastrointest Canc. 54: 1017-1030.

- Hofmann L, Forschner A, Loquai C, Goldinger SM, Zimmer L, et al. (2016). Cutaneous, gastrointestinal, hepatic, endocrine, and renal side-effects of anti-PD-1 therapy. European Journal of Cancer. 60: 190-209.

- Feng Y, Guo K, Jin H, Jiang J, Wang M, et al. (2024). Adverse events of neoadjuvant combination immunotherapy for resectable cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Immunol. 14: 1269067.

- Cheung VTF, Brain O. (2020). Immunotherapy induced enterocolitis and gastritis – What to do and when? Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology. 49: 101703.

- Martins F, Sofiya L, Sykiotis GP, Lamine F, Maillard M, et al. (2019). Adverse effects of immune-checkpoint inhibitors: epidemiology, management and surveillance. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 16: 563-580.

- Castillero F, Castillo-Fernández O, Jiménez-Jiménez G, Fallas-Ramírez J, Peralta-Álvarez MP, et al. (2019). Cancer Immunotherapy-Associated Hypophysitis. Future Oncol. 15: 3159-3169.

- Sun L, Meng C, Zhang X, Gao J, Wei P, et al. (2023). Management and prediction of immune-related adverse events for PD1/PDL-1 immunotherapy in colorectal cancer. Front Pharmacol. 14: 1167670.

- Lote H, Starling N, Pihlak R, Gerlinger M. (2022). Advances in immunotherapy for MMR proficient colorectal cancer. Cancer Treatment Reviews. 111: 102480.

- Mettu NB, Ou FS, Zemla TJ, Halfdanarson TR, Lenz HJ, et al. (2022). Assessment of Capecitabine and Bevacizumab With or Without Atezolizumab for the Treatment of Refractory Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 5: e2149040.

- Ree AH, Šaltytė Benth J, Hamre HM, Kersten C, Hofsli E, et al. (2024). First-line oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy and nivolumab for metastatic microsatellite-stable colorectal cancer-the randomised METIMMOX trial. Br J Cancer. 130: 1921-1928.

- Kanani A, Veen T, Søreide K. (2021). Neoadjuvant immunotherapy in primary and metastatic colorectal cancer. British Journal of Surgery. 108: 1417-1425.

- Liu M, Liu Q, Hu K, Dong Y, Sun X, et al. (2024). Colorectal Cancer with BRAF V600E Mutation: Trends in Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Treatment. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 104497.

- Garralda E, Sukari A, Lakhani NJ, Patnaik A, Lou Y, et al. (2022). A first-in-human study of the anti-LAG-3 antibody favezelimab plus pembrolizumab in previously treated, advanced microsatellite stable colorectal cancer. ESMO Open. 7: 100639.

- Hou X, Zheng Z, Wei J, Zhao L. (2022). Effects of gut microbiota on immune responses and immunotherapy in colorectal cancer. Front Immunol. 13: 1030745.

- He Y, Zhang X, Zhu M, He W, Hua H, et al. (2023) Soluble PD-L1: a potential dynamic predictive biomarker for immunotherapy in patients with proficient mismatch repair colorectal cancer. J Transl Med. 21: 25.

- Yeh YS, Tsai HL, Chen PJ, Chen YC, Su WC, et al. (2023). Identifying and clinically validating biomarkers for immunotherapy in colorectal cancer. Expert Review of Molecular Diagnostics. 23: 231-241.

- Ajab SM, Zoughbor SH, Labania LA, Östlundh LM, Orsud HS, et al. (2024). Microbiota composition effect on immunotherapy outcomes in colorectal cancer patients: A systematic review. PLoS ONE. 19: e0307639.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.