Idiopathic Chronic Eosinophilic Pneumonia with ILD: A Case Report

by Sana Zafar1, Ujala Razaq1, Faheem Anjum2, Fatima Gul3, Mansoor Aman4, Haseeb Manzoor5

1CF at Tameside & Glossop NHS Trust, UK

2IMT3 at Salford Royal NHS Trust, UK

3SCF at Stepping Hill NHS Trust, UK

4IMT3 at Hull Royal Infirmary NHS, UK

5ST5 at Stepping Hill Hospital, UK

*Corresponding author: Sana Zafar, CF at Tameside & Glossop NHS Trust, UK

Received Date: 22 October 2024

Accepted Date: 25 October 2024

Published Date: 29 October 2024

Citation: Zafar S, Razaq U, Anjum F, Gul F, Aman M, Manzoor H, et al (2024) Idiopathic Chronic Eosinophilic Pneumonia with ILD: A Case Report. Ann Case Report. 9: 2031. https://doi.org/10.29011/2574-7754.102031

Abstract

Idiopathic CEP is an extremely rare medical disease, an individual and rather specific representative of the entire list of respiratory diseases. It has both systemic and lung involvement, blood eosinophilia, peripheral opacities in chest X-Rays and clears up readily with corticosteroids.1 Pathologically CEP shows an intraalveolar exudate of eosinophils, histiocytes and occasionally shapeless material and eosinophilic interstitial infiltrations; interstitial fibrosis is sometimes present locally but the alveolar septa are not involved and the fibrosis is minor [1].

The condition has an excellent response to oral corticosteroids. However, the high proportion of relapses and the presence of pulmonary fibrosis explain the need for rigorous and sustained follow-up in idiopathic chronic eosinophilic pneumonia [2]. As mentioned in this information, health care providers play an instrumental role when it comes to this condition. It is noteworthy that idiopathic chronic eosinophilic pneumonia associates with significant and definite history of asbestos exposure [3].

The authors present a case of a 90-year-old man who had gradual progressive and severe pneumonia and dysphasia within one month of admission. The present report describes a case of CEP due to long-term asbestos exposure with progression in fibrotic lung disease. The patient complained of general weakness, blue discolouration, loss of consciousness, and dysphasia. Chest CT scans demonstrated opacities that were predominantly within the anesthetic areas sub-pleural and these cleared after commencement of corticosteroids.

Keywords: Chronic Eosinophilic Pneumonia; Therapy; CEP; Asbestos Exposure; Interstitial Lung Disease.

Introduction

Idiopathic Chronic Eosinophilic Pneumonia (CEP) is a rare and great pathologic condition, which is the cause of persistent pulmonary inflammation. CEP is, therefore, idiopathic, which implies that the cause of the disease is unknown. The respiratory illness most often occurs in adults and is associated with gradual development of symptoms. Clinical symptoms may include a cough that does not disappear, difficulty in breathing, fatigue, and high body temperature.

Diagnosis of CEP can sometimes be a complex process because the condition has no special symptoms and can be easily mistaken for other conditions of lung origin. Physicians remain very instrumental in the use of clinicopathological correlation as a means of arriving at a diagnosis since clinical features accompanied by laboratory investigations and imaging will output the probable diagnosis [4].

Early diagnosis is crucial in identifying CEP. Key diagnostic criteria for CEP include the presence of respiratory symptoms for at least one month, increased eosinophil count in Broncho alveolar lavage fluid, and the exclusion of other potential causes of eosinophilic lung diseases. Chest X-rays and computed tomography (CT) scans may reveal patchy infiltrates, consolidation, or ground-glass opacities.

The exact prevalence of ICEP in Europe is still undetermined. It accounts for 0-2.5% of cases in various interstitial lung disease registries. Affecting all age groups, ICEP typically presents at an average age of 45 and is extremely uncommon in children. Interestingly, women are almost twice as likely to experience this condition compared to men for reasons yet to be explained. Interestingly, a mere 10% or fewer of individuals who experience ICEP are active tobacco users. Recent findings suggest that radiation treatment for breast cancer might be a contributing factor in triggering ICEP [5].

The clinical presentation of this disease is mainly characterized by gradual worsening of breathing over time, coughing, struggling to speak, reduced eating, cyanosis and fatigue. The signs are vague and typically involve both respiratory and general symptoms, which can be subacute or chronic [4]. As a result, these symptoms usually persist for at least one month before a diagnosis is reached. In rare cases, the onset is more rapid, with symptoms lasting as little as two weeks. The condition responds very well to oral corticosteroid treatment. Nonetheless, relapses often occur during the reduction or cessation of therapy.

Case

Our case study was about a 90-year-old man who presented with symptoms of rapidly progressive pneumonia and speech difficulties that had been ongoing for one month.

The patient was admitted on 22.04-23 with blue colour lips and cyanosis. The onset of the illness was noted to have started at noon on 22-4-23. The ambulance crew noted that the patient was last seen at 10:30 am and was well before going to his room. When the crew went into the patient’s room at noon, the patient was found unconscious and unsure of how long he had been in that state. He was laid on his side and was later noted to be confused, un-oriented, and slurring his words. Medication history revealed fexofenadine, allopurinol, quinine, lactulose, omeprazole, B150 Prisl, and furosemide. Upon admission, blood work revealed an increased eosinophil count, raising suspicion of eosinophilic pneumonia or vasculitis.

He was referred to the Department of Infection for further evaluation of rapidly progressive pneumonia, which had been ongoing for one month. The initial symptoms included persistent cough, shortness of breath, fatigue, fever, unintentional weight loss, slurring speech, and feeling unwell.

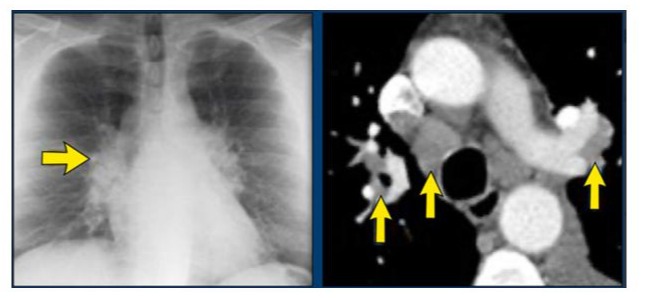

The patient had a past medical history significant for congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, chronic hyponatremia, substance use disorder, chronic kidney disease, alcohol excess, peripheral vascular disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, thyroid disorder, ex-smoking history, hearing loss, recurrent falling, and small vessel disease. These comorbidities, particularly the history of smoking and alcohol excess, are known risk factors for the development and progression of CEP. The patient’s extensive medical history suggests a complex health profile that may have contributed to the development of CEP (Figures 1-3).

Figure 1: Chest X -Ray shows mixed ground glass opacities and Chest CT reveals consolidation in the upper lobes with cavitation.

He had a history of military service from 1951 to 1954 and had travelled to various locations, including the Suez Canal area, Sri Lanka, Yemen, and Malaysia. However, there was no recent travel within 30 to 40 years. The patient worked as a heating engineer and had significant exposure to asbestos-containing insulation without using personal protective equipment. Although the patient admitted to having worked for over thirty years as a heating engineer involving coming across and handling asbestos the patient had denied any recent exposure. Some occupational history coupled with highly probable exposure to asbestos makes the patient candidate for an environmental cause of CEP.

An average eosinophil count was recorded by blood tests conducted in January/February 2022. However, the patient reported, and as indicated in the medical records, allopurinol was begun in March 2022, marking the initial onset of eosinophilia. As a matter of fact, there was a record of how administration of allopurinol resulted in increased eosinophils. As the patient had a history of military service and travel, infectious etiologies were considered only in Thus, Strongyloides infection. This led to ordering of serology for Strongyloides. In addition, the medications that may induce eosinophilia, allopurinol and PPIs were withdrawn from the patient.

On radiographic review, imaging studies led to the diagnosis of idiopathic chronic eosinophilic pneumonia (CEP). The diagnosis of idiopathic CEP was made using the criteria that referred to presence of respiratory symptoms for more than one month, with increased count of eosinophils in BALF and exclusion of other causes of eosinophilic lung diseases. Because of the presence of severe symptoms and relatively quick progression, the patient required initiation in treatment with glucocorticoids, predominantly prednisone. The patient responded positively to the treatment, gradually improving symptoms and lung function.

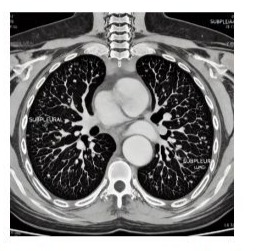

Figure 2: High-resolution CT scan obtained with patient prone shows sub pleural lines parallel to inner chest wall. Note sub pleural dotlike opacities.

Upon admission, the patient presented with intermittent fever ranging from 37.6 to 38.4 degrees Celsius. Although fine crackles were observed, no wheezes or cardiac murmurs were detected during the physical examination, except for finger clubbing. The chest X-ray revealed reticulonodular opacities in both lung fields. Additionally, the high-resolution CT scan with 1.5mm thick slices showed the presence of ground-glass opacities and honeycombing. The CT findings also showed the presence of asbestos-related pleural plaques. Given the patient’s clinical presentation and the imaging findings, idiopathic CEP was suspected as a potential underlying cause. Blood tests were conducted to assess eosinophil levels and other relevant markers. The laboratory results showed a high leucocyte count of 17.4x10^9/L with 57% eosinophils (1.05 x 10^9/L) and low hemoglobin (107 g/L).

Over the next few days, the patient’s breathing gradually worsened, and he had difficulty speaking total words. Although he started eating and drinking, his food intake reduced, and he began coughing and producing large volumes of hemophilic green sputum. He had some improvement in breathing but reported vomiting after eating. Crackles were heard on free breath, and the patient was started on occupational therapy. He was prescribed Apixaban 2-5 mg RD, and there was a consideration to increase this to smg BD as the patient did not meet the criteria to require dose reduction (Age, wt., creatinine).

Subsequent evaluations on 26-04-2023 revealed a non-productive cough with large volumes of hemophilic green sputum. Breathing had improved slightly, but eating was still problematic, leading to vomiting. On 27-04-2023, cystic changes were seen in the pancreas, and the patient had bilateral respiratory crackles. Imaging studies demonstrated asbestosis-related pleural plaques and cystic changes in the pancreas. The patient also developed a urinary tract infection caused by Proteus mirabilis. Normocytic anemia was detected in the blood work.

Figure 3: Bronchoscopic view showing idiopathic Chronic Eosinophilic Pneumonia (CEP).

Following treatment initiation, the patient demonstrated significant improvement in his overall condition. He became alert, well-oriented, and able to speak in complete sentences. Lung examinations revealed casual crepitations, indicating resolving pulmonary changes. Blood tests were conducted to assess eosinophil levels and other relevant markers. The laboratory results showed an average eosinophil count on 5-01-23. A leucocyte count of 9.3 x 10^9/L with an average eosinophils count of 0.20 x 10^9/L) was seen. Haemoglobin improved since the day of admission, but still, the patient was normocytic anemia (124 g/L).

As of the latest update, the patient is alert, well-oriented, and feels much better. Casual crepitations were heard in the lungs, and the patient could transfer from the bed to the wheelchair and selfpropel himself a few feet in the wheelchair. He reported being able to stand and “stretch legs” and usually does 180° but did not have a family to bring in a wheelchair. He is currently talking in complete sentences. However, the lack of family support posed challenges for wheelchair usage. Regular follow-up visits were planned to monitor his progress and manage potential complications.

Despite initial respiratory and gastrointestinal complications, the patient showed significant improvement with appropriate treatment and rehabilitation. This case emphasizes the importance of considering multiple etiologies in elderly patients with respiratory symptoms and highlights the need for comprehensive management approaches.

Discussion

Anyone who has been diagnosed with CEP will know that diagnosing the condition can be difficult because it often mimics other lung diseases with similar symptoms. Clinical presentation, correlation with clinical imaging laboratory findings helps the physicians make a diagnosis in making the diagnosis of CEP; there are three critical elements to consider respiratory symptoms for over a month, raised eosinophil count in BAL F and ruling out other causes of eosinophilic lung diseases.

Idiopathic Chronic Eosinophilic Pneumonia is a challenging respiratory disease which determines persistent lung inflammation [5]. Despite the unclear etiology of CEP, timely diagnosis and appropriate glucocorticoid administration will reduce inflammation and improve lung function. Since CEP is a very rare disease, knowing it by healthcare employees and further research is vital to improving identified knowledge and, subsequently, patients’ treatment [6].

There are many causes of pulmonary infiltrates with blood eosinophilia. These are drug-induced reactions that affect the lungs, infections from mycobacteria, fungi, or parasitic organisms, Churg-Strauss syndrome, other inflammatory disorders of the airways, for example, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, idiopathic chronic eosinophilic pneumonia or idiopathic hyper eosinophilic syndrome [6]. Idiopathic CEP is a systemic disease that primarily affects the pulmonary system. Such signs are fever, weight loss, cough or dyspnoea, elevated eosinophil count in the blood and opacities discovered on chest radiography. Management of idiopathic CEP is usually done by short courses of corticosteroids, which gives near immediate response.

This patient presented with a substantial past medical history of asbestos exposure as a heating engineer and within the last month was prescribed allopurinol for gout. Even though those conditions may be linked to previous military duty or worldwide traveling, infectious causes were considered less likely [7]. Thus, after further working up, the patient was diagnosed with idiopathic chronic eosinophilic pneumonia (CEP). This report therefore recommends that drug-induced eosinophilia and asbestos exposure should be considered as possibilities in the patients presenting with atypical pneumonia [6].

The patient’s medical history, including asbestos exposure and travel to multiple locations, makes him susceptible to various infections and respiratory conditions. The eosinophilic pneumonia and asbestosis-related pleural plaque could be linked to his history of asbestos exposure. His UTI caused by Proteus Mirabilis and normocytic anemia could be due to other factors. The patient’s condition is being monitored, and treatment is ongoing.

Conclusion

This case report focuses on the asymptomatic and heterogeneous chronic symptoms in a patient experiencing idiopathic eosinophilic pneumonia with past asbestos exposure. The respiratory, gastrointestinal, and urinary tract involvement with the disease underlines the need for a systematic assessment. Corticosteroids used when diagnosis of eosinophilic pneumonia is early in patients with asbestos exposure, may prove beneficial.

References

- Yoshida K, Shijubo N, Koba H, Mori Y, Satoh M, et al (1994) Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia progressing to lung fibrosis. European Respiratory Journal. 7:1541-4.

- Jeong YJ, Kim KI, Seo IJ, Lee CH, Lee KN, et al (2007) Eosinophilic Lung Diseases: A Clinical Radiologic, and Pathologic Overview. RadioGraphics. 27: 617-639.

- Carrington CB, Addington WW, Goff AM, Madoff IM, Marks A, et al (1969) Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia. N Eng J Med. 280: 787-798.

- Fox B, Seed WA (1980) Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia. Thorax. 35: 570-580.

- Peter JJ, Sicilian L, Gaensler EA (1988) Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia. A report of 19 cases and a review of the literature. Medicine. 67: 154-162.

- Sano, S., Yamagami, K. & Yoshioka, K. (2009) Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia: a case report and literature review. Cases Journal 2: 7735.

- Colby TV (1992) Pathologic aspects of bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia. Chest. 102:38S-43S.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.