Idiopathic Cervical Dystonia and Cervical Dystonia in Parkinson’s Disease -A Common Pathophysiology, Clinical Pattern and Treatment?

by Marita F Thiel1, Jaroslaw Slawek2,3, Emir Berberovic1, Wolfgang H Jost1,4*

1Parkinson-Klinik Ortenau, Germany

2Department of Neurology, Neurodegenerative Disorders and Neuroimmunology, Faculty of Health Sciences, Medical University of Gdańsk, Poland

3Clinical Department of Neurology&Stroke, St. Adalbert Hospital, Gdańsk, Poland

4Department of Neurology, University of Saarland, Germany

*Corresponding author: Wolfgang H Jost, Parkinson-Klinik Ortenau, Wolfach, Germany

Received Date: 02 January 2026

Accepted Date: 19 January, 2026

Published Date: 23 January 2026

Citation: Thiel MF, Slawek J, Berberovic E, Jost WH (2026) Idiopathic Cervical Dystonia and Cervical Dystonia in Parkinson’s Disease -A Common Pathophysiology, Clinical Pattern and Treatment? J Neurol Exp Neural Sci 8: 169. https://doi.org/10.29011/25771442.100069

Abstract

More than 30% of Parkinson’s patients are affected by the symptom of cervical dystonia (CD). Cervical dystonia, which is classified among the focal dystonias, can also occur fully independently of Parkinson’s disease as an isolated symptom. A clear distinction is not possible when both diseases occur together. The etiology has not as yet been clarified. The therapeutic effect of injections of botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT) into the afflicted muscles has been well established in appropriate studies and is thus considered the therapy of choice. The current study situation, however, does not permit differentiating diagnostics or therapy for cervical dystonia between Parkinson patients and non-Parkinson patients. The decisive factors in achieving therapeutic success lie within the level of experience of treating physicians, the precise diagnosis by means of the col-cap concept and a precisely targeted BoNT injection, best made under sonographic or EMG controls. Further investigations are necessary to clarify and differentiate CD in PD and idiopathic CD.

Key Contribution: Cervical dystonia is a frequently observed symptom of Parkinson’s disease. Current studies estimate a prevalence of approximately 30 per cent. In addition, CD also occurs as idiopathic focal dystonia. Our article aims to draw attention to the fact that CD is understood as a symptom of PD, whereas CD as focal dystonia is classified as a clinical condition. In this context, our article provides an overview of both entities highlights similarities and raises questions that need to be clarified in further studies.

Introduction

Cervical dystonia (CD) is the most common form of idiopathic dystonia, occurring between the ages of 40 and 60 and more frequently in women (1.5-1.9:1) [1]. Along with e.g. blepharospasm, tongue and laryngeal dystonia, it is a form of focal dystonia, which by definition affects only one region of the body. Cervical dystonia affects the head and neck muscles which result in a plethora of various positions and movements, usually accompanied by tremor or myoclonic jerks. It may result in repetitive movements or fixed position. Epidemiological studies showed a highly variable prevalence from 28 till 183 cases per million, however reliable data are lacking [2,3]. Dystonia can be triggered or aggravated by voluntary [4] movements and is associated with excessive muscle activation [2]. In a majority of cases CD is idiopathic, but in symptomatic or inherited ones it may be the result of other diseases (e.g. Wilson’s Disease or THAP1/DYT6 gene mutation). However, clinical spectrum of motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease (PD) at the time of initial diagnosis does not include dystonia (except the dystonic posture of the affected upper limb) it may be prominent and painful at the mid- or late-stage disease. Painful dystonic postures may include the foot dystonia during the night (early morning dystonia) and during the motor fluctuations (bi-phasic dyskinesia, wearing off) and may affect a neck/head region as well [4]. Therefore, dystonia is relatively common in PD, however CD seems to be a neglected problem. Idiopathic CD is effectively treated with BoNT injections or Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS), but this kind of treatment is not offered to PD patients. In clinical trials and they are still off-label treatments.

In PD, cervical dystonia can manifest itself as motor fluctuations, wearing-off, or biphasic dystonia, or even worsen over time, and it is often accompanied by pain [5]. If left untreated, idiopathic CD as well as CD in PD remains irreversibly fixed, resulting in a permanent abnormal posture of the head and/or neck. Many patients perceive this poor posture as a stigma and, as a result, it has serious psychological consequences. In many cases, it is associated with stress, anxiety, depression and sleep disorders and often leads to negative coping strategies such as harmful substance use or social withdrawal [6]. Refering to PD Sitek et al [7]. discuss an important aspect in their paper. They were able to show that only 50% of PD patients have sufficient self-awareness of peak dose dyskinesias and abnormal movements, including CD. The question of whether improved self-awareness could improve or even prevent CD in PD cannot be answered at present and would require further study. The aim of this paper is to analyze the prevalence and phenomenology of CD in PD, it’s pathogenesis, poor outcomes (pain, deformities) and suggested treatment options.

Cervical Dystonia as a Symptom of Parkinson’s Disease

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common neurodegenerative disease worldwide, closely followed by PD [8]. PD is characterized by a variety of motor symptoms (bradykinesia, rigidity, tremor at rest) and non-motor symptoms (neuropsychiatric: depression, sleep problems, apathy, cognitive decline and psychosis and dysautonomic symptoms (orthostatic hypotension, constipation and hyperactive bladder), and the clinical presentation is heterogeneous [5]. Dystonias are associated with PD and may precede the clinical diagnosis in inherited forms (e.g. PARK2 mutations) or may occur late as a clinical manifestation of motor fluctuations. It means that in some PD forms it may be not related to dopaminergic treatment, but is a part of PD clinical spectrum. CD is one of the most common dystonias in PD. Currently, no reliable data is available. Our data and experience show that 34 % of PD patients are affected. This is nearly consistent with the figures reported by Kashihara et al. [9]. Of course, the subgroup of PD patients with cervical dystonia is rather small in the total group of all CD patients.The diagnosis of CD must be made carefully and should be given particular attention in the early stages, when it is not immediately apparent. In 2022, we examined 532 patients diagnosed with PD (342 of whom were male, 190 female). We were able to show that 34% of patients had CD [10]. For the diagnosis of cervical dystonia, we used the col-cap concept first presented by Reichel [11] which applies to CD in PD as well as to all other cervical dystonias. Accompanying non-motor symptoms may occur, primarily including depression, pain, insomnia, and the stigma associated with the symptom. The symptoms do not correlate with the severity of CD. Emotional health and pain are the factors that particularly impair the patients’ quality of life [12]. With only limited data available, no conclusions can be drawn regarding the correlation with, for example, duration and severity of PD.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of CD in PD and non-Parkinson patients has not yet been completely understood. The existing explanatory models are heterogeneous and leave many questions unanswered. Dystonia occurs, among other things, in relation to age and gender, as a possible consequence of dopaminergic therapy, or on the basis of genetic disposition. Dopaminergic medication can improve dystonia in PD, provided it occurs exclusively in the off state. Dystonia, that is not limited to the off state can be improved or even worsened by dopaminergic medication. Nevertheless, the conclusion that dopamine-signaling pathways are involved in the pathology is often discussed. This is supported by the fact that drug-induced blockade of dopaminergic neurons, which causes both dystonia and Parkinsonism [13] is well known. Early studies observed dystonia in PD in both patients treated with levodopa and levodopa-naive patients. The cause of dystonia was initially localized in the basal ganglia [14]. In the further course, a variety of different theories were discussed. Chu et al. [15] considered low-frequency oscillations in the globus pallidus internus (local field potentials) to be the cause. It was assumed that these lowfrequency oscillations were responsible for the pathophysiology of dystonia [15]. Dystonia and parkinsonism, including PD, are characterized by the loss of nigrostriatal neurons and the associated decrease in dopamine levels. This leads to increased activity of striatal cholinergic interneurons: another explanatory model [16] for the pathophysiology of CD in PD. In 2001, Jankovic et al. [17] discussed varying affinity states of dopaminergic receptors. With increasing dopaminergic deficit, even high-affinity dopaminergic receptors could no longer function adequately, which, according to their assumption, would result in Parkinsonism and dystonia [17]. However, since not all PD patients develop dystonia, this thesis remains incomplete.

DBS is available as a form of therapy for patients with idiopathic CD. One would expect that there is an explanatory model underlying its mode of action. However, the pathophysiological basis that could explain the positive outcome of DBS is unclear. Neuronal inhibition, excitation, or disruption of neuronal activity are theories that have been discussed [18]. It therefore remains unclear whether, and if so why, dystonia and PD are associated with each other via a common pathomechanism and why both respond to DBS. The knowledge gap is even greater when considering cases in which DBS, used to treat CD, initiated parkinsonism [19].

Theories from the recent past, some of which are based on imaging diagnostics, have shown that cortico-basal gangliathalamo-cortical, as well as cortico-ponto-cerebello-thalamocortical loops could be important for the pathogenesis of dystonia. The cerebellum appears to play an important role. In their review, Morigaki et al. discuss the pathogenesis of dystonia as a consequence of dysfunction of motor networks involving the basal ganglia and cerebellum [20]. Although recent explanatory approaches have opened up new perspectives, the question of pathogenesis remains unanswered. The pathogenesis of idiopathic dystonia and the pathogenesis of dystonia in PD have not been conclusively clarified.

Clinical Patterns of CD in PD when Compared to Tdiopathic CD

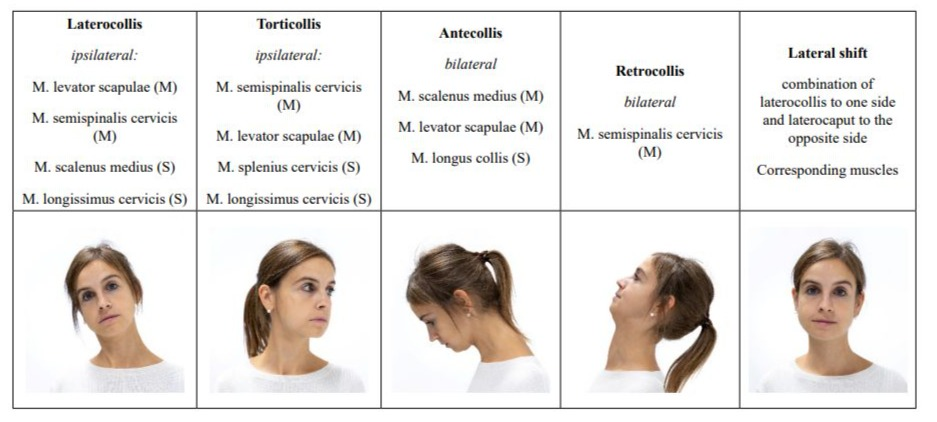

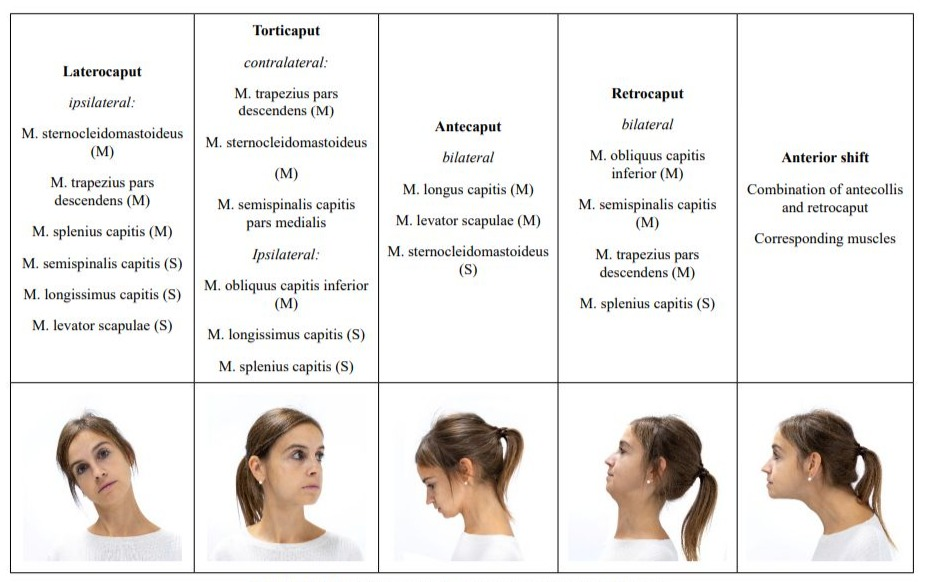

The treating physician is required to perform a thorough physical examination upon initial consultation. The initial medical history can offer an opportunity to conduct an initial inspection of head and neck posture. To do this, position yourself directly opposite the patient and request them to remove any distracting clothing and jewelry during the consultation. This provides ample opportunity to closely observe the patient’s head and neck posture and even to detect any subtle cervical dystonia [21] (Table 1-2).

Table 1: Col-cap-Concept: different types of cervical dystonia.

The use of the col-cap-concept limits misdiagnoses which would inevitably lead to incorrect and thus ineffective treatment. In addition to the precise classification of CD, pseudodystonias must be recognized. These usually require further diagnostic testing and, above all, a different therapy [2]. In terms of differential diagnosis, antecollis is of particular importance because it must be clearly distinguished from dropped head. The latter is a weakness of the neck extensors, while antecollis is a dystonic activation of more ventral neck muscles [4,21].

|

Possible causes of Pseudodystonia |

|

Dystonic (tonic) Tics |

|

Central or peripheral nerve damage: vestibulopathy, trochlear palsy, etc. |

|

Degenerative spinal or joint changes: scoliosis, kyphosis, atlanto-axial, shoulder subluxation, etc. |

|

Musculoskeletal causes: Arnold-Chiari malformation, congenital Klippel-Feil syndrome, Satoyoshi syndrome, Sandifer syndrome, congenital torticollis, etc. |

|

Neuromuscular causes: Stiff person syndrome, Isaacs syndrome, among others. |

|

Electrolyte imbalance: hypocalcemia, hypomagnesemia, alkalosis |

|

Electrolyte imbalance: hypocalcemia, hypomagnesemia, alkalosis |

Table 2: Possible causes of pseudodystonia. According to [2].

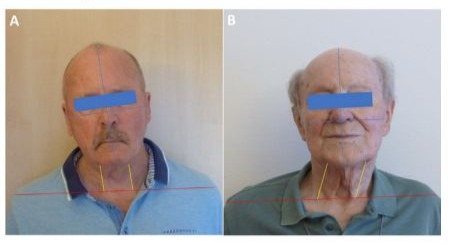

The col-cap concept [11] describes 10 subtypes. The muscles involved are identified based on the anatomical planes of movement between the head and neck. Combinations of subtypes can be precisely described and subsequently treated using this concept. The col-cap concept is generally valid for the diagnosis of CD, regardless of whether CD occurs as a symptom of PD or as the sole symptom. In any case, precise anatomical knowledge of the origin, insertion, and function of the respective muscles is essential. Other anatomical structures can be used to confirm the diagnosis. The larynx, for example, can be used to distinguish the rotation between torticollis and torticaput. If it is positioned centrally, it will be a torticaput, while if the larynx is positioned more laterally, it will be a torticollis. Although the head can also be rotated with the torticollis, the responsible muscles are located between C2 and C7. In a torticollis, however, the insertion and origin of the affected muscles are between C2 and the skull [22]. A lateral shift is not always easy to diagnose. It is characterized by a laterocollis on the one side, with a laterocaput on the contralateral side. Figure 1 illustrates the difference between laterocollis (A) and lateral shift (B). An anterior shift, on the other hand, is the combination of antecollis and retrocaput. If a unilateral shoulder elevation is present at the same time, this should be considered a compensation for the malposition and not classified as dystonic [10]. Cervical dystonia always presents a complex picture that requires intensive and thorough examination. The goal of the examination is to identify the leading muscle group, as the most affected muscle should be treated first. This applies to patients with PD and to patients with isolated dystonia. Sonography is recommended as an adjunct to the physical examination, especially when the dystonia is complex and advanced. Sonography allows the target muscle to be visually localized. The injection can then be accurately performed by an experienced examiner under sonographic visual guidance. While sonography offers the best accuracy for the experienced examiner, electromyography (EMG) can provide additional clues as to whether the selected muscle is even partly responsible for the dystonia. However, solid experience is also required here to avoid confusing random EMG activity with dystonic activity [22]. Dystonic activity would be between 4-7 Hz. It must be considered that the sensitivity of the EMG for the detection of dystonic activity is comparatively low at 17% [23]. Nevertheless, several studies have shown that patients who received a BoNT injection under EMG guidance experienced a longer-lasting benefit from the injection compared to those who were injected based on mere manual palpation alone [24]. A reliable diagnosis of CD therefore involves several steps. The initial step is the medical history, which may already provide clues to possible pseudodystonia, followed by a physical examination, which should be based on the col-cap concept. The best therapeutic success is guaranteed by the concomitant use of sonography to reliably localize the selected muscle, if possible in combination with EMG to monitor muscle activity. Regardless of whether the diagnosis is an isolated dystonia or dystonia associated with PD, the experience of the examiner is the fundamental prerequisite for a reliable diagnosis and successful treatment.

Figure 1: A: laterocollis, B: lateral shift.

Frequency and Subtypes of Cervical Dystonia

The col-cap concept describes ten subtypes of cervical dystonia. Only the lateral shift and sagittal shift subtypes are defined combinations of two subtypes. Apart from that various combinations between the remaining eight subtypes might occur. When this is the case, the major variant is usually named first, followed by the minor variant. The number of studies on the frequency of the subtypes of CD is very limited and does not allow for any general conclusions. This applies to pure CD as well as to CD in PD. A prospective multicenter study from 2020 [25] addressed the topic for the first time and described the frequency of the individual subtypes of cervical dystonia. 306 patients with CD were examined, without differentiating between PD patients and non-PD patients. The subtype most frequently seen in this study was torticaput, occurring in 49% of patients with CD. Almost half of these were associated with a laterocaput, and another 20.7% with a retrocaput. Laterocaput was the second most common subtype, occurring at just less than 17%. The remaining subtypes occurred in significantly lower percentages of less than 10%. Pure forms with only a single subtype were seen in 16.3% of patients. Shift variants have been described in 14.7% of patients with CD, but only 3.9% of these were diagnosed. Statistically, each patient had 2.5 subtypes. This study concludes that the subtypes affecting head posture were the most common, with torticollis being the most common. Combinations were common in this study (83.7%), while the occurrence of but one single subtype was rather rare [25]. Another study from 2016 [26] examined pure CD and described its clinical and demographic characteristics in 1,477 patients with CD. Very limited data are available on this topic to date. The authors do not describe subtypes of CD, but rather the region in the body in which CD first occurred and/or was subsequently observed

secondarily. Therefore, the col-cap concept understandably does not apply. The authors noted that in the majority of patients, cervical dystonia began in the neck region (78.5%). If the dystonia initially affected another body region, it spread to the neck region in 13.3%.

In our study from 2022 [10] laterocollis and antecollis were the most common in PD. Antecollis was diagnosed in third place at 21%. Torticollis, which affected almost half of the patients in the former study, ranks among the lowest at 4% in the study of CD in PD patients. The opposite is true for shift variants. 30% of PD patients with CD presented a shift variant, while in the 2020 study, this was diagnosed in only 3.9% of patients. However, the distribution of the subtypes shows a clear similarity in the frequency of laterocollis. It occurs in 17% and 18% of both studies, respectively. A low frequency is found in both studies for the antecollis, retrocollis, and retrocaput subtypes. Combinations of subtypes were relatively rare in PD patients (12.1%), while the ratio was almost reversed in PD and non-PD patients. In these patients, 83.5% of patients were diagnosed with a combination of several subtypes.

Although there are some similarities between both studies, significant differences also emerge. General conclusions cannot be drawn. It is also important to consider that the 2020 study examined PD and non-PD patients, while the 2022 study refers exclusively to PD patients. No conclusions can be drawn from the results of the study on pure CD [26] when compared with the data from the other two studies from 2020 and 2022. This is most likely due to the fact that the research question does not target individual subtypes and thus the col-cap concept is not applicable, which virtually precludes a comparison. The current data are insufficient to derive significant and practice-relevant findings. We need further studies in the future that allow us to derive results on the frequency of the subtypes of CD (Table 3).

|

Subtypes of CD (after the Col-cap concept) |

Subtypes of CD in Parkinson and non- Parkinson patients [21] n=306 |

Subtypes of CD in Parkinson patients [14] n=181 |

|

Laterocollis |

< 10 % |

23 % |

|

Laterocaput |

17% |

18% |

|

Torticollis |

< 10 % |

1 % |

|

Torticaput |

49% |

4 % |

|

Antecollis |

< 10 % |

21 % |

|

Antecaput |

< 10 % |

0% |

|

Retrocollis |

< 10 % |

0% |

|

Retrocaput |

< 10 % |

0.5 % |

|

Lateral shift |

14.7 % of the patients were diagnosed with shift forms |

19 % |

|

Anterior shift |

11 % |

|

|

16.5% of the patients had a single |

87.9 % of the patients had a single |

|

|

subtype, the other patients had combinations of subtypes. |

subtype, the other patients had combinations of subtypes. |

Table 3: Number of subtypes of CD in PD and non-Parkinson patients.

Botulinum Neurotoxin in the Treatment for Cervical Dystonia

Botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT) is one of the most potent neurotoxic proteins. A product of the anaerobic bacterium Clostridium botulinum, it blocks the release of acetylcholine in the synaptic cleft, resulting in muscle weakness. For several decades, BoNT A has been used therapeutically to treat cervical dystonia as onabotulinumtoxin A, abobotulinumtoxin A, and incobotulinumtoxin A, as well as BoNT B as rimabotulinumtoxin B [27] and is now considered the preferred treatment. Study results show success rates between 58 and 95 percent [28]. Crucial to therapeutic success are an exact diagnosis of the respective subtype and reliable localization of the affected muscles. Based on the col-cap concept, the main muscles should be selected for injection first, followed by the muscles of the subtype. Approximately 57% of PD patients with cervical dystonia also have dystonic head tremor. With precise injection, these patients do not require higher doses than patients without tremor [29]. The manufacturer’s instructions provide some guidance for dosage selection, as they are based on extensive study results. This applies to the start of treatment as well as to subsequent treatments, which have been established at approximately 12-week intervals. For abobotulinumtoxin, a starting dose of 500 U is recommended. If well tolerated, the dose can be increased to 1,000 U. For ona- and incobotulinumtoxinA, doses of up to 400 U are recommended, while for RIMA-BoNTB,

a dose of 10,000 U is recommended [30]. Experts recommend dividing the dose into 1 to 4 injection sites [31]. Comparably effective treatment outcomes have also been described for lower doses injected under sonographic guidance. This was demonstrated in a multicenter study involving 305 patients. BoNT/A injections into the leading muscle(s) diagnosed using the col-cap concept and performed under sonographic guidance produced consistently positive results [29]. To date, there is no clear data on whether there is a connection between treatment outcome and clinical progression or the appearance of CD. Furthermore, it should not be forgotten that cervical dystonia progresses over time and other symptoms may accompany the clinical picture [32].

Treatment Failure and Possible Side Effects

In the event of treatment failure, the first step is to verify whether the diagnosis was correct. In the event of incorrect assignment of the main and/or subtype, the wrong muscles would have been injected. The respective literature assumes that this occurs in 37% of treatment failures and explains inadequate treatment results. Patients who were injected with BoNT again after reevaluation of the diagnosis showed subsequent success rates of over 70% [33]. There is controversy regarding the severity of CD and dose adjustment. There is evidence that patients with only mild symptoms subjectively perceive little benefit from treatment [34]. Controversially, there is evidence that patients with severe symptoms experience less benefit [35]. At the same time, it should be noted that there are differences in assessment of the outcome between physician and patient, and that a considerable proportion of patients discontinue treatment [36]. Treatment failure could also be related to the failure to reach deeper muscles with the injection. This is conceivable, for example, in the antecaput and antecollis [36]. No reliable data is available on the treatment of PD patients in advanced stages with CD. At our clinic, we tend to be cautious when it comes to dosing. This is especially true in cases of antecollis, which affects 21 percent of patients. BoNT injections to treat antecollis in patients with advanced disease should be administered with particular caution, and we tend to use reduced doses in these cases. A younger age at treatment and shorter intervals between initial and follow-up treatments could contribute to a positive treatment outcome [32]. In the case of a lack of therapeutic response, immune resistance to BoNT A must also be considered. This can also occur after a purely aesthetic BoNT treatment [37]. So that in the case of treatment failure after therapeutic BoNT treatment, possible previous aesthetic treatments with BoNT should also be considered. Apart from that neutralizing antibodies, so-called NABs (neutralizing antibodies against botulinum toxin), are known.

They can be the result of previous exposure to botulinum toxin or the result of a vaccination, such as that which was common for the American military during the Gulf War [38]. In any case, they weaken the therapeutic success or even make it impossible. It is also understandable that treatment with BoNT can lead to weakening of the neck muscles [22]. Another possible side effect after BoNT treatment is dysphagia. Patterson et al. [39] were able to show that patients diagnosed with PD were equally affected by this as patients without Parkinson’s disease. The duration of treatment success and the dosage were also the same in both groups. 144 patients were examined, of whom 24 were diagnosed with PD. In this study, the average age of Parkinson’s patients (n=24) was slightly higher than that of non-Parkinson’s patients (59.6 years), at around 64 years, while the gender distribution of Parkinson’s patients favoured male patients (13 male and 11 female patients). Among nonParkinson’s patients (n= 120), the number of male patients (27) was significantly lower than the number of female patients (93). With regard to Parkinson’s patients, there was no exact differentiation in terms of disease duration and stage. However, 4 of the 24 PD patients had atypical Parkinson’s syndrome. In this retrospective study, both groups were treated with onabotulinum toxin A. The average dose for non-Parkinson’s patients was 263.7 ± 101.3 units. The average dose for PD patients with cervical dystonia was 233.6 ± 93.8 units. Dysphagia was observed equally in both groups during treatment with onabotulinum toxin A. The result was consistent with the result of the drug’s approval study. In the group of non-PD patients, 108 cases were recorded, of which 21 patients experienced dysphagia after treatment. No dysphagia was reported among the 4 cases with atypical Parkinson’s syndrome. Among the 20 remaining Parkinson’s patients with cervical dystonia, 4 patients experienced dysphagia after treatment. An important conclusion of the study was that patients with cervical dystonia in PD can be treated with BoNT just as safely as patients with cervical dystonia of other aetiologies.

Summary

Up to 34% of patients diagnosed with PD can be affected by CD during the course of their illness. Independent of PD, CD is the most common form of dystonia. The group of PD patients with CD accounts for only a small proportion of the total group of CD patients. While CD alone is considered a separate clinical picture, we consider CD in Parkinson’s disease more of an additional symptom. The pathophysiology is unclear in both cases. In many cases, it is accompanied by non-motor symptoms such as depression, sleep disturbances, or pain. The question of whether there is a difference between PD and other patients with cervical dystonia, remains open and requires further study. The presentation of CD is complex in every case and requires considerable experience from the examiner. The col-cap concept is an effective starting point for diagnosis and therapeutic success and is used in all cases of cervical dystonia. The treatment of choice is BoNT, which is used equally well in PD and in patients with idiopathic CD. There is currently no evidence of possible differences in the treatment of CD in PD compared to idiopathic CD. This also applies to possible treatment failure and side effects. The current study situation is insufficient to draw conclusions as to whether the pathophysiology, presentation, progression of dystonia, causes of treatment failure and side effects are identical in PD and other patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.T. and W.J.; validation, M.T., W.J. and J.S.; investigation, M.T.; writing—original draft preparation, M.T. and J.S.; writing—review and editing, W.J. and J.S.; visualization, M.T. and E.B.; supervision, W.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Disclosures: Prof Jaroslaw Slawek received honoraria for lectures and advisory boards from Abbvie, Ipsen, Merz

Conflicts of Interest

- MT an EB received honoraria for consultant work from Neuraxpharm

- JS received honoraria for lectures and advisory boards from Abbvie, Ipsen, Merz

- W.J. works as a consultant and speaker for Abbvie, Ipsen and Merz

References

- Medina A, Nilles C, Martino D, Pelletier C, Pringsheim T (2022) The Prevalence of Idiopathic or Inherited Isolated Dystonia: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis. Mov Disord Clin Pract 9(7): 860-868.

- Albanese A, Bhatia K, Bressman SB, Delong MR, Fahn S,et al.(2013) Phenomenology and Classification of Dystonia: A Consensus Update. Movement Disorders 28(7): 863-873.

- Defazio G, Jankovic J,Giel JL,Papapetropoulos S (2013) Descriptive Epidemiology of Cervical Dystonia. Tremor and Other Hyperkinetic Movements 3 :03.

- Ashour R, Jankovic J (2006) Joint and Skeletal Deformities in Parkinson’s Disease, Multiple System Atrophy, and Progressive Supranuclear Palsy. Movement Disorders 21(11): 1856-1863.

- Poewe WH,Lees AJ,Stern GM (1988) Dystonia in Parkinson’s Disease: Clinical and Pharmacological Features. Ann Neurol 23(1): 73-78.

- Gowling H, O’Keeffe F, Eccles FJR (2024) Coping Strategies, Distress and Wellbeing in Individuals with Cervical Dystonia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Psychol Health Med 29(7): 1313-1330.

- Sitek EJ, Sołtan W, Wieczorek D, Schinwelski M, Robowski P, et al. (2013) Self‐awareness of Executive Dysfunction in Huntington’s Disease: Comparison with Parkinson’s Disease and Cervical Dystonia. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 67(1): 59-62.

- Kowal SL, Dall TM, Chakrabarti R, Storm MV, Jain A (2013) The Current and Projected Economic Burden of Parkinson’s Disease in the United States. Movement Disorders 28(3): 311-318.

- Kashihara K,Imamura T (2013) Frequency and Clinical Correlates of Retrocollis in Parkinson’s Disease. J Neurol Sci 324(1-2):106-108.

- Thiel MF, Altmann CF, Jost WH (2022) Cervical Dystonia in Parkinson’s Disease: Frequency of Occurrence and Subtypes. Neurol Neurochir Pol 56(4): 379-380.

- Reichel G (2011) Cervical Dystonia: A New Phenomenological Classification for Botulinum Toxin Therapy. Basal Ganglia 1(1): 5-12.

- Klingelhoefer L, Kaiser M, Sauerbier A, Untucht R, Wienecke M,et al. (2021) Emotional Well-Being and Pain Could Be a Greater Determinant of Quality of Life Compared to Motor Severity in Cervical Dystonia. J Neural Transm 128(3): 305-314.

- Tomiyama M (2025) Drug-Induced Parkinsonism as Viewed from Neurologist. Brain Nerve 77(6): 715-719.

- Mink JW (2018) Basal Ganglia Mechanisms in Action Selection, Plasticity, and Dystonia. European Journal of Paediatric Neurology 22(2): 225-229.

- Chen CC, Kühn AA, Trottenberg T, Kupsch A, Schneider GH,et al.(2006) Neuronal Activity in Globus Pallidus Interna Can Be Synchronized to Local Field Potential Activity over 3–12 Hz in Patients with Dystonia. Exp Neurol 202(2): 480-486.

- Dang MT, Yokoi F, Cheetham CC, Lu J, Vo V,et al. (2012) An Anticholinergic Reverses Motor Control and Corticostriatal LTD Deficits in Dyt1 ΔGAG Knock-in Mice. Behavioural Brain Research 226(2): 465-472.

- Jankovic J, Tintner R (2001) Dystonia and Parkinsonism. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 8(2):109-121.

- Chiken S, Nambu A (2016) Mechanism of Deep Brain Stimulation: Inhibition, Excitation, or Disruption?.The Neuroscientist 22(3): 313322.

- Zauber SE, Watson N, Comella CL, Bakay RAE,Metman LV (2009) Stimulation-Induced Parkinsonism after Posteroventral Deep Brain Stimulation of the Globus Pallidus Internus for Craniocervical Dystonia. J Neurosurg 110(2): 229-233.

- Morigaki R, Miyamoto R, Matsuda T, Miyake K, Yamamoto N,et al. (2021) Dystonia and Cerebellum: From Bench to Bedside. Life 11(8): 776.

- Jost WH (2017) How Do I Treat Cervical Dystonia With Botulinum Toxin by Using Ultrasound?. Mov Disord Clin Pract 4(4): 647.

- Jost WH, Tatu L (2015) Selection of Muscles for Botulinum Toxin Injections in Cervical Dystonia. Mov Disord Clin Pract 2(3): 224-226.

- Tyślerowicz M, Kiedrzyńska W, Adamkiewicz B, Jost WH, Sławek J (2020) Cervical Dystonia-Improving the Effectiveness of Botulinum Toxin Therapy. Neurol Neurochir Pol 54(3): 232-242.

- Tijssen MA, Münchau A, Marsden JF, Lees A, Bhatia KP,et al. (2002) Descending Control of Muscles in Patients with Cervical Dystonia. Movement Disorders 17(3): 493-500.

- Jost WH, Tatu L, Pandey S, Sławek J, Drużdż A,et al.(2020)Frequency of Different Subtypes of Cervical Dystonia: A Prospective Multicenter Study According to Col–Cap Concept. J Neural Transm 127(1): 45-50.

- Norris SA, Jinnah HA, Espay AJ, Klein C, Brüggemann N, et al.(2016) Clinical and Demographic Characteristics Related to Onset Site and Spread of Cervical Dystonia. Movement Disorders 31(12): 1874-1882.

- Jankovic J (2009) Disease-Oriented Approach to Botulinum Toxin Use. Toxicon 54(5): 614-623.

- Pandey S, Kreisler A, Drużdż A, Biering-Sørensen B, Sławek J,et al.(2020)Tremor in Idiopathic Cervical Dystonia-Possible Implications for Botulinum Toxin Treatment Considering the Col-Cap Classification. Tremor and Other Hyperkinetic Movements 10: 13.

- Jost WH, Drużdż A, Pandey S, Biering-Sørensen B, Kreisler A,et al.(2021) Dose per Muscle in Cervical Dystonia: Pooled Data from Seven Movement Disorder Centres. Neurol Neurochir Pol 55(2):174178.

- Sławek J, Jost WH (2021) Botulinum Neurotoxin in Cervical Dystonia Revisited-Recent Advances and Unanswered Questions. Neurol Neurochir Pol 55(2):125-132.

- Wissel J, Kanovsky P, Ruzicka E, Bares M, Hortova H, et al.(2001) Efficacy and Safety of a Standardised 500 Unit Dose of Dysport ® (Clostridium Botulinum Toxin Type A Haemaglutinin Complex) in a Heterogeneous Cervical Dystonia Population: Results of a Prospective, Multicentre, Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Parallel Group Study. J Neurol 248(12):1073-1078.

- Erro R, Picillo M, Pellecchia MT, Barone P (2023) Improving the Efficacy of Botulinum Toxin for Cervical Dystonia: A Scoping Review. Toxins (Basel) 15(6): 391.

- Jinnah HA, Goodmann E, Rosen AR, Evatt M, Freeman A,et al. (2016) Botulinum Toxin Treatment Failures in Cervical Dystonia: Causes, Management, and Outcomes. J Neurol 263(6):1188-1194.

- Hefter H, Samadzazeh S, Rosenthal D (2021) The Impact of the Initial Severity on Later Outcome: Retrospective Analysis of a Large Cohort of Botulinum Toxin Naïve Patients with Idiopathic Cervical Dystonia. J Neurol 268(1): 206-213.

- Marciniec M, Szczepańska-Szerej A, Rejdak K (2020) Cervical Dystonia: Factors Deteriorating Patient Satisfaction of Long-Term Treatment with Botulinum Toxin. Neurol Res 42(11): 987-991.

- Jinnah HA, Comella CL, Perlmutter J, Lungu C, Hallett M (2018) Longitudinal Studies of Botulinum Toxin in Cervical Dystonia: Why Do Patients Discontinue Therapy? Toxicon 147: 89-95.

- Ho WWS, Chan L, Corduff N, Lau WT, Martin MU,et al.(2023) Addressing the Real-World Challenges of Immunoresistance to Botulinum Neurotoxin A in Aesthetic Practice: Insights and Recommendations from a Panel Discussion in Hong Kong. Toxins (Basel) 15(7): 456.

- Pittman PR, Hack D, Mangiafico J, Gibbs P, McKee KT,et al.(2002) Antibody Response to a Delayed Booster Dose of Anthrax Vaccine and Botulinum Toxoid. Vaccine 20(16): 2107-2115.

- Patterson A, Almeida L, Hess CW, Martinez-Ramirez D, Okun MS,et al.(2016) Occurrence of Dysphagia Following Botulinum Toxin Injection in Parkinsonism-Related Cervical Dystonia: A Retrospective Study. Tremor and Other Hyperkinetic Movements 6: 379.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.