Hypokalemia: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management

by Majed M Alosaimi*, Monther N Alazwari, Abdulmajeed Alotaibi, Mutlaq E Alotaibi

Al Hada Armed Forces Hospital, Taif, Saudi Arabia

*Corresponding author: Majed M Alosaimi, Al Hada Armed Forces Hospital, Taif, Saudi Arabia

Received Date: 08 December 2025

Accepted Date: 12 December 2025

Published Date: 15 December 2025

Citation: Alosaimi MM, Alazwari MN, Alotaibi A, Alotaibi ME (2025) Hypokalemia: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management. J Surg 10:11511 https://doi.org/10.29011/2575-9760.011511

Background

Potassium is the most abundant intracellular cation in human body. Plasma potassium level is strictly regulated to maintain cellular function. Potassium transmembrane gradient (30 intracellular to 1 extracellular) maintains intracellular electronegativity, which is essential for cell depolarization and action potential propagation [1]. Potassium is also critical for other cellular functions; it is a cofactor for many enzymes, modulates protein function, and participates in signaling pathways [2]. The optimal potassium level for maintaining health is likely to be between 4 and 5 mmol/L. Deviation from this range is associated with increased mortality [3,4]. For individuals prone to cardiac arrhythmia, a higher range of 4.5-5 mmol/L is associated with better outcomes [5]. However, hypokalemia is defined as a serum potassium level below 3.5 mmol/L in most laboratories. Hypokalemia is a common electrolyte disturbance in clinical practice, affecting over 20% of hospitalized patients [6,7]. It is particularly prevalent among critically ill patients and those with cancer [8,9]. Hypokalemia is frequently diagnosed in asymptomatic patients as a laboratory abnormality [10-12]. However, low serum potassium levels can cause disturbances in excitable tissues, including the heart, skeletal, and smooth muscles, leading to arrhythmia, weakness, and ileus [10]. Electrocardiogram (ECG) abnormalities associated with hypokalemia include T-wave flattening, the appearance of a U-wave, and a prolonged QT interval. Chronic hypokalemia impairs urinary concentration, causes polyuria, and may lead to Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) [13].

Regulation of Serum Potassium Level

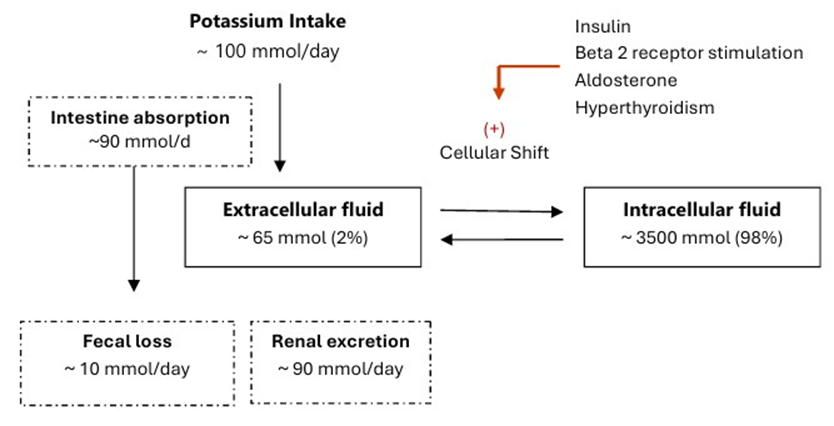

The total body potassium is approximately 3500 mmol, with 98% intracellular and only 2% (~ 65 mmol) in the extracellular fluid (interstitial fluid and plasma) [14]. Potassium is abundant in the diet and is readily absorbed by the small intestine into the extracellular fluid. Less than 10 mmol/day of potassium is excreted in the stool [15]. Gastrointestinal potassium absorption is primarily passive and largely unregulated [16]. After consuming a meal rich in potassium (e.g., 70 mmol), it is critical to transfer “buffer” the absorbed potassium into the intracellular fluid. This is mediated by insulin and other factors and is essential to prevent life-threatening postprandial hyperkalemia [17]. Other factors that increase potassium shift into the intracellular compartment include high plasma potassium level, beta-2 receptor stimulation, aldosterone, and hyperthyroidism [18-21]. Rarely, genetic defects in the cellular transport can cause an intracellular potassium shift and hypokalemia (hypokalemic periodic paralysis) [22] Figure 1.

Figure 1: Distribution of potassium in the body.

The kidneys excrete dietary potassium loads and maintain potassium homeostasis. Potassium is readily filtered by the glomeruli. The daily filtered potassium load is approximately 720 mmol (assuming a glomerular filtration rate of 180 L/d and a plasma potassium concentration of 4 mmol/L). The kidneys reabsorb most of the filtered potassium in the proximal tubule and the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle, while fine-tuning regulation occurs in the distal nephron (distal part of the distal tubule, connecting tubule, and collecting duct) [23]. Potassium absorption in the proximal nephron segments is largely unregulated [24]. Only 10% of the filtered potassium reaches the distal nephron. Potassium is reabsorbed and excreted in these nephron segments. The net potassium balance is the net result of these two processes. In the principal cells of the distal nephron, potassium excretion is facilitated by sodium reabsorption via the Epithelial Sodium (Na+) Channel (ENaC). Aldosterone enhances the gene expression of the channel protein, facilitates its insertion into the apical membrane rather than its degradation, increases its opening, and increases the cellular activity of Na-K ATPase [25]. The increased sodium reabsorption and Na-K ATPase activity in the principal cells create favorable electric and concentration gradients that facilitate potassium excretion via the Renal Outer Medullary Potassium (ROMK) channel. Low magnesium concentration promotes the opening of ROMK channels and decreases Na-K ATPase activity, resulting in increased urinary potassium excretion [26]. Hypomagnesemia also reduces upstream sodium reabsorption in the distal tubule, thereby enhancing potassium excretion by the principal cells [27]. In type A intercalated cells, potassium is actively absorbed at the luminal border. When potassium levels are sufficient, it exits the cell through the apical membrane. However, in cases of potassium deficiency, it exits via the basolateral membrane [28]. Other factors that increase potassium excretion in the distal nephron segments include increased urinary flow and metabolic alkalosis [29-31]. Kidney potassium excretion follows a circadian rhythm, increasing during the day and decreasing in the evening, which aligns with the higher intake during the day and lower intake at night [32]. Additionally, high potassium intake induces kidney potassium excretion [33]. This precise regulatory system implies that hypokalemia results from one of three fundamental disturbances: inadequate intake, transcellular shift, or excessive loss.

Causes of Hypokalemia

Pseudohypokalemia

Accurate measurement of serum potassium levels requires strict compliance with pre-analytical protocols [34]. During phlebotomy, fist-clenching and prolonged tourniquet time should be avoided, as these actions can increase potassium release from the muscles and raise potassium level, potentially masking hypokalemia [35]. Pseudohypokalemia can occur in blood samples from patients with leukemia or essential thrombocytosis, in which metabolically active cells take up plasma potassium before it is measured [36]. This issue can be prevented by processing the blood sample promptly, transporting and storing the sample at 4°C, or using a point-of-care potassium analyzer.

Decrease Potassium Intake

Hypokalemia is rarely caused by reduced potassium intake, as potassium is abundant in the diet [37]. However, hypokalemia is commonly seen in critically ill patients and postoperatively [3840]. In these situations, other risk factors for hypokalemia, such as the use of diuretics, bowel preparation, and gastrointestinal surgery, are often present.

Intracellular Potassium Shift

Insulin treatment can promote an intracellular potassium shift, leading to hypokalemia [41]. This effect is particularly noted during the management of diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state. Similarly, activation of the Beta-2 adrenergic receptor is a well-documented cause of acute transient hypokalemia [42]. This condition arises from cAMP-mediated activation of the Na-K ATPase pump, leading to an intracellular shift of potassium. This can be observed in patients receiving beta-2 agonists, those with pheochromocytoma, and those experiencing elevated catecholamine levels, such as during acute myocardial infarction, critical illness, and severe stress. Thyrotoxicosis can also cause hypokalemia by increasing the activity of the Na-K ATPase pump [43]. Additionally, increased cellular potassium uptake is observed in refeeding syndrome and during treatment of megaloblastic anemia [44,45].

Increased Potassium Loss

Gastrointestinal Potassium Loss

Abnormal potassium loss from the gastrointestinal tract and kidneys is the most common cause of hypokalemia [46]. Gastrointestinal secretions (gastric, hepatobiliary, pancreatic, and intestinal) contain 10-20 mmol per liter of potassium. In addition, diarrhea contains a significant amount of potassium, ranging from 45–60 mmol/L [47]. In patients with diarrhea or vomiting, concurrent volume depletion triggers the release of aldosterone, which subsequently enhances sodium reabsorption and potassium excretion by the kidneys. Increased gastrointestinal potassium losses can also be caused by tumors such as VIPoma, villous adenoma, and Zollinger–Ellison syndrome, as well as by hepatobiliary drainage, ileostomy, and malabsorption.

Renal Potassium Loss

In the presence of hypokalemia, the kidneys conserve potassium, leading to reduced potassium excretion. Key considerations for kidney potassium wasting include enhanced sodium delivery to the distal nephron, alkalosis, elevated renin levels, increased mineralocorticoid or glucocorticoid levels, presence of a nonreabsorbable anion, increased urinary flow, and hypomagnesemia. Diuretics that act upstream of the distal nephron segments increase sodium and fluid delivery to these sites, thereby promoting potassium secretion [48]. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, such as acetazolamide, inhibit sodium and bicarbonate reabsorption in the proximal tubule, resulting in increased sodium and bicarbonate delivery to the distal nephron segments. This phenomenon is also observed in conditions such as proximal renal tubular acidosis and Fanconi syndrome. Loop diuretics inhibit sodium and potassium reabsorption in the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle, leading to increased distal sodium delivery and renal potassium loss. Bartter syndrome, an inherited tubulopathy characterized by transport dysfunction in the thick ascending loop of Henle, has similar effects. Thiazide diuretics act on the distal tubule to inhibit Na-Cl cotransport, thereby increasing sodium delivery to the distal nephrons. Gitelman syndrome is characterized by impaired reabsorption of sodium and chloride in the distal tubule. All of these conditions and agents, including carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, proximal renal tubular acidosis, Fanconi syndrome, loop diuretics, Bartter syndrome, thiazide diuretics, and Gitelman syndrome, can induce secondary hyperaldosteronism, thereby amplifying their effect on distal tubular potassium excretion. Acute alkalosis directly affects the principal cells of the collecting duct by increasing potassium excretion through the ROMK channels, whereas acidosis has the opposite effect. In cases of chronic metabolic alkalosis and compensated respiratory acidosis, the filtered bicarbonate levels increase, thereby promoting potassium excretion. Some penicillins, along with ketoacids in diabetic ketoacidosis and during fasting, act as non-reabsorbable anions that stimulate potassium excretion. The common causes of hypokalemia are summarized in Table 1. When faced with hypokalemia, clinicians must answer a series of sequential physiological questions to arrive at the correct diagnosis.

|

Decrease potassium intake |

|

|

Transcellular potassium shift |

Drug induced · Insulin treatment · Beta 2 receptor stimulation (bronchodilators, decongestants, and Epinephrine) Thyrotoxicosis Refeeding syndrome Treatment of megaloblastic anemia Hypokalemic periodic paralysis |

|

Increased gastrointestinal tract potassium loss |

Infection diarrhea Tumors · Vipoma · Villous adenoma of the colon · Zollinger–Ellison syndrome Vomiting* Hepatobiliary drain Ileostomy Malabsorption |

|

Increased urinary potassium loss |

Diuretics (Loop and thiazide diuretics, acetazolamide) Hypomagnesemia Metabolic alkalosis Renal tubular acidosis Fanconi’s syndrome Tubulopathy (Bartter’s syndrome, Gitelman’s syndrome, Liddle syndrome) Renin excess (Renal artery stenosis, renin-secreting tumor, and malignant hypertension) Aldosterone excess (Conn’s syndrome) Corticosteroid excess (exogenous steroids, Cushing’s syndrome, salt-retaining congenital adrenal hyperplasia, licorice) |

Table 1: Common causes of hypokalemia.

Evaluation

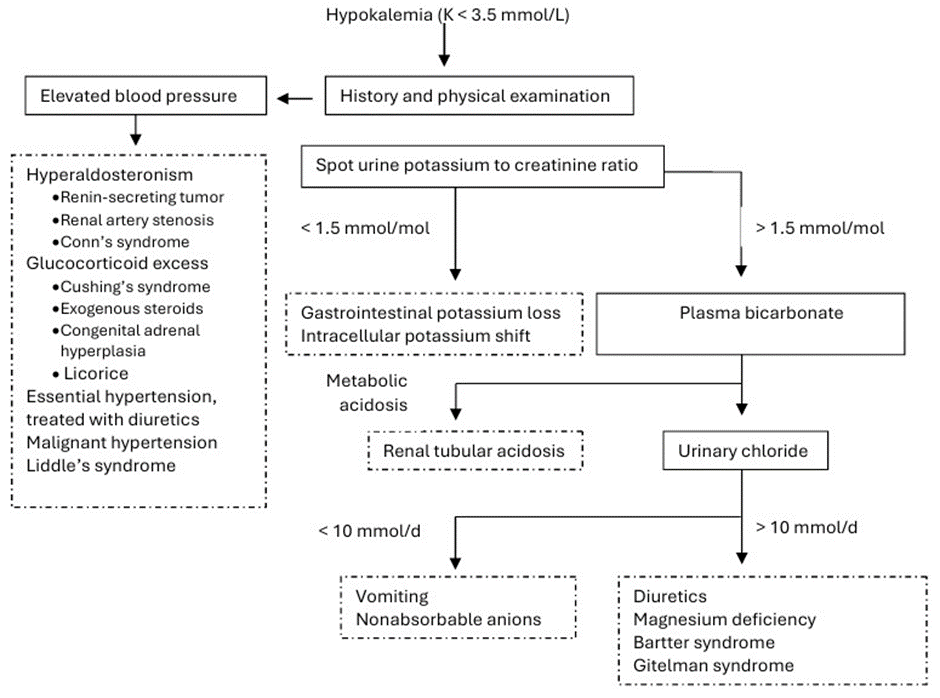

Effective management of hypokalemia requires identifying and addressing its underlying causes. In most cases, the cause is evident from the patient’s history and physical examination. When the cause is not apparent, the initial diagnostic evaluation should include blood pressure, blood gas analysis, serum magnesium, and urinary potassium, sodium, and chloride levels. Elevated blood pressure and metabolic alkalosis may indicate elevated aldosterone levels (renin-secreting tumors, renal artery stenosis, and Conn’s syndrome). Glucocorticoid excess also causes sodium retention and hypokalemia (Cushing’s syndrome, exogenous steroid use, and salt-retaining congenital adrenal hyperplasia). An activating mutation in the Epithelial Sodium Channel (ENaC) results in Liddle syndrome, a disorder marked by hypertension, hypokalemia, and metabolic alkalosis [49]. However, similar findings can arise from malignant hypertension or when treating essential hypertension with thiazide or loop diuretics. If the patient’s blood pressure is normal, it is important to measure urinary potassium levels to evaluate the renal response to potassium deficiency. In cases of dietary potassium deficiency, gastrointestinal potassium loss, or transcellular potassium shift, the kidneys conserve potassium, leading to decreased urinary potassium excretion. A spot urine potassium-to-creatinine ratio greater than 2.5 mmol/mol suggests a renal cause of hypokalemia [50]. Blood gas analysis helps narrow the differential diagnosis of hypokalemia of renal origin. Metabolic acidosis indicates renal tubular acidosis, whereas alkalosis indicates diuretic use and tubulopathy (Bartter and Gitelman syndromes) [51]. Magnesium level measurement is a frequently neglected yet essential test. Hypomagnesemia leads to renal potassium wasting, making hypokalemia resistant to correction unless magnesium is concurrently repleted [52]. Urinary sodium and chloride levels are useful for assessing chronic hypokalemia. In renal tubular disorders and current diuretic use, they are coupled (urine Na+/Cl− ratio 1), whereas in cases of vomiting and laxative abuse, they are uncoupled [53]. Figure 2 summarizes the diagnostic approach for hypokalemia.

Figure 2: Evaluation of hypokalemia.

Treatment

The management of hypokalemia is determined by its severity, presence of symptoms, and underlying etiology. In the absence of an intracellular potassium shift, potassium decreases by 1 mmol/L for each 200–400 mmol total body potassium deficit [54]. The primary strategy for the prevention and management of mild chronic cases involves ensuring adequate dietary intake of potassium. Potassium-rich foods are listed in Table 2.

|

Food |

Potassium in milligrams per serving |

|

Apricots, dried, ½ cup |

755 |

|

Lentils, cooked, 1 cup |

731 |

|

Squash, acorn, mashed, 1 cup |

644 |

|

Prunes, dried, ½ cup |

635 |

|

Raisins, ½ cup |

618 |

|

Potato, baked, flesh only, 1 medium |

610 |

|

Kidney beans, canned, 1 cup |

607 |

|

Orange juice, 1 cup |

496 |

|

Soybeans, mature seeds, boiled, ½ cup |

443 |

|

Banana, 1 medium |

422 |

|

Milk, 1%, 1 cup |

366 |

|

Spinach, raw, 2 cups |

334 |

|

Chicken breast, boneless, grilled, 3 ounces |

332 |

|

Yogurt, fruit variety, nonfat, 6 ounces |

330 |

|

Salmon, Atlantic, farmed, cooked, 3 ounces |

326 |

|

Beef, top sirloin, grilled, 3 ounces |

315 |

|

Molasses, 1 tablespoon |

308 |

|

Tomato, raw, 1 medium |

292 |

|

National Institutes of Health Office of Dietary Supplements. (2022, June 2). Potassium: Fact sheet for health professionals: https://ods. od.nih.gov/factsheets/Potassium-HealthProfessional/ |

|

Table 2: Potassium Content of Selected Foods.

In the management of mild hypokalemia (K≥3), oral potassium supplementation is preferred over intravenous potassium treatment. The oral route is physiological, facilitates gradual correction, and minimizes the risk of iatrogenic hyperkalemia. Commonly available formulations include slow-release potassium chloride tablets (600 mg, providing 8 mmol of potassium) and potassium chloride liquid, available as 10% (providing 15 mmol per 10 mL) and 20 % (providing 30 mmol per 10 mL) solutions. An oral dose ranging from 40 to 60 mmol typically increases serum potassium levels by 0.5 to 1.0 mmol/L; however, this effect is often temporary, and potassium repletion over several days is required [55]. Patients with hypokalemia due to loop or thiazide diuretics benefit from adding a potassium-sparing diuretic to their regimen [56]. Intravenous potassium replacement is reserved for patients who cannot take potassium orally, have moderateto-severe hypokalemia (serum potassium <3.0 mmol/L), or have cardiac arrhythmias, muscle weakness, or rhabdomyolysis. For peripheral venous administration, potassium should be diluted in normal saline (0.9% sodium chloride), and dextrose-containing solutions must be avoided, as the induced insulin release can acutely worsen hypokalemia. The infusion rate should not exceed 10 mmol/h through a peripheral vein to prevent pain and phlebitis. Common regimens include 40 mmol of Potassium Chloride (KCl) in 500 ml of normal saline, infused over 4 h, or 10 mmol added to a minibag of 100 ml of normal saline administered every hour. Serum potassium levels should be checked every 4–6 h during the initial phase of replacement. In life-threatening situations, such as severe hypokalemia (potassium 2.5 mmol/L) or arrhythmias, more rapid correction via a central venous catheter may be necessary. A potassium chloride infusion rate of 20 mmol/h is generally used in this setting [57]. This approach mandates continuous cardiac monitoring in a controlled care setting. Serum potassium should be measured every 2–4 h until the level rises above 3.0 mmol/L and symptoms resolve, after which the infusion rate must be reduced. A critical exception to these replacement principles is hypokalemia caused by an intracellular potassium shift, as seen in hypokalemic periodic paralysis. Under these conditions, the total body potassium level is normal. Aggressive potassium supplementation may precipitate severe rebound hyperkalemia once the transcellular shift is reversed.

Conclusion

Hypokalemia poses a clinical challenge that requires a thorough understanding of potassium homeostasis. Effective management requires a systematic diagnostic approach that considers factors such as blood pressure, acid-base balance, and urinary potassium excretion. Treatment should be specifically tailored to the underlying cause, allowing clinicians to address the root cause rather than merely supplementing potassium. This strategy not only prevents recurrence but also improves the patient outcomes.

References

- Wright S.H (2004) Generation of resting membrane potential. Adv Physiol Educ 28: 139-142.

- Rosenhouse-Dantsker A (2025) Potassium in Health and DiseaseNutrition and Transport Mechanisms 160.

- Krogager, M. L (2017) Short-term mortality risk of serum potassium levels in hypertension: a retrospective analysis of nationwide registry data. Eur Heart J 38: 104-112.

- Collins, A. J (2017) Association of serum potassium with all-cause mortality in patients with and without heart failure, chronic kidney disease, and/or diabetes. Am J Nephrol 46: 213-221.

- Christian J (2025) Increasing the Potassium Level in Patients at High Risk for Ventricular Arrhythmias. New England Journal of Medicine 393: 1979-1989.

- Paice BJ (1986) Record linkage study of hypokalaemia in hospitalized patients. Postgrad Med J 62: 187-191.

- Nilsson E (2017) Incidence and determinants of hyperkalemia and hypokalemia in a large healthcare system. Int J Cardiol 245: 277-284. Kraft MD, Btaiche IF, Sacks GS, Kudsk KA (2005) Treatment of electrolyte disorders in adult patients in the intensive care unit. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 62: 1663-1682.

- Berardi R (2019) Electrolyte disorders in cancer patients: a systematic review. J Cancer Metastasis Treat 5: 79.

- Weiner ID, Wingo CS (1997) Hypokalemia--consequences, causes, and correction. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 8: 1179-1188. Liamis G (2013)Electrolyte disorders in community subjects: prevalence and risk factors. Am J Med 126: 256-263.

- Kieneker LM (2017) Plasma potassium, diuretic use and risk of developing chronic kidney disease in a predominantly White population. PLoS One 12: e0174686.

- Reungjui S (2007) Thiazide-induced subtle renal injury not observed in states of equivalent hypokalemia. Kidney Int 72: 1483-1492.

- Forbes GB, Lewis A M (1956) Total sodium, potassium and chloride in adult man. J Clin Invest 35: 596-600.

- Agarwal R, Afzalpurkar R, Fordtran JS (1994) Pathophysiology of potassium absorption and secretion by the human intestine. Gastroenterology 107: 548-571.

- Rose BD, Post TW (2001) Clinical Physiology of Acid-Base and Electrolyte Disorders. (McGraw-Hill, Medical Pub. Division, New York. STERNS RH, Cox M, FEIG PU, SINGER I (1981) Internal potassium balance and the control of the plasma potassium concentration. Medicine 60: 339-354.

- Adrogué HJ, Madias NE (1981) Changes in plasma potassium concentration during acute acid-base disturbances. Am J Med 71: 456-467.

- Williams ME (1985) Catecholamine modulation of rapid potassium shifts during exercise. New England Journal of Medicine 312: 823827.

- Brown MJ, Brown DC, Murphy MB (1983) Hypokalemia from beta2receptor stimulation by circulating epinephrine. New England Journal of Medicine 309: 1414-1419.

- Kung AWC (2006) Thyrotoxic periodic paralysis: a diagnostic challenge. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91: 2490-2495.

- Jurkat-Rott K (2000) Voltage-sensor sodium channel mutations cause hypokalemic periodic paralysis type 2 by enhanced inactivation and reduced current. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 97: 9549-9554.

- Gumz ML, Rabinowitz L, Wingo CS (2015) An integrated view of potassium homeostasis. New England Journal of Medicine 373: 6072.

- Palmer BF (2015) Regulation of potassium homeostasis. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 10: 1050-1060.

- Pitzer AL, Beusecum JPV, Kleyman TR, Kirabo A (2020) ENaC in SaltSensitive Hypertension: Kidney and Beyond. Curr Hypertens Rep 22: 69. Touyz RM, de Baaij JHF, Hoenderop JGJ (2004) Magnesium Disorders. New England Journal of Medicine 390: 1998-2009.

- Huang CL, Kuo E (2007) Mechanism of hypokalemia in magnesium deficiency. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 18: 26492652.

- Roy A, Al-bataineh MM, Pastor-Soler NM (2015) Collecting duct intercalated cell function and regulation. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 10: 305-324.

- Palmer BF, Clegg DJ (2016) Physiology and pathophysiology of potassium homeostasis. Adv Physiol Educ 40: 480-490.

- Stanton BA, Giebisch G (1982) Effects of pH on potassium transport by renal distal tubule. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology 242: F544-F551.

- Ellison DH, Terker AS (2015) Why your mother was right: how potassium intake reduces blood pressure. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc 126: 46-55.

- Costello HM, Johnston JG, Juffre A, Crislip GR, Gumz ML (2022) Circadian clocks of the kidney: function, mechanism, and regulation. Physiol Rev 102: 1669-1701.

- Preston RA, Afshartous D, Rodco R, AlonsoAB, Garg D (2015) Evidence for a gastrointestinal–renal kaliuretic signaling axis in humans. Kidney Int 88: 1383-1391.

- Lippi G, Guidi GC, Mattiuzzi C, Plebani M (2006) Preanalytical variability: the dark side of the moon in laboratory testing. Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (CCLM) 44: 358-365.

- Don BR, Sebastian A, Cheitlin M, Christiansen M, Schambelan M (1990) Pseudohyperkalemia caused by fist clenching during phlebotomy. New England Journal of Medicine 322: 1290-1292.

- Adams PC, Woodhouse KW, Adela M, Parnham A (1981) Exaggerated hypokalaemia in acute myeloid leukaemia. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 282: 1034-1035.

- Intakes, S. C. on the S. E. of D. R., Electrolytes, P. on D. R. I. for & Water. Dietary Reference Intakes for Water, Potassium, Sodium, Chloride, and Sulfate. (National Academies Press, 2005).

- Kraft MD, Btaiche IF, Sacks GS, Kudsk KA (2005) Treatment of electrolyte disorders in adult patients in the intensive care unit. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 62: 1663-1682.

- Zhu Q (2018) Prevalence and risk factors for hypokalemia in patients scheduled for laparoscopic colorectal resection and its association with post-operative recovery. BMC Gastroenterol 18: 152.

- Pan P, Zhang Z, Zhang X, Jiang Q, Xu Z (2024) Postoperative Prevalence and Risk Factors for Serum Hypokalemia in Patients with Primary Total Joint Arthroplasty. Orthop Surg 16: 72-77.

- Nguyen TQ, Maalouf NM, Sakhaee K, Moe OW (2011) Comparison of insulin action on glucose versus potassium uptake in humans. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 6: 1533-1539.

- Brown MJ, Brown DC, Murphy MB (1983) Hypokalemia from beta2receptor stimulation by circulating epinephrine. New England Journal of Medicine 309: 1414-1419.

- Kardalas E, Paschou SA, Anagnostis P, Muscogiuri G, Siasos G, Vryonidou A(2018) Hypokalemia: a clinical update. Endocr Connect 7: R135-R146.

- Krutkyte G, Wenk L, Odermatt J, Schuetz P,Stanga Z, et al.(2022) Refeeding syndrome: a critical reality in patients with chronic disease. Nutrients 14: 2859.

- Lawson DH, Parker JL, Murray RM, Hay G (1970)HYPOKALÆMIA IN MEGALOBLASTIC ANÆMIAS. The Lancet 296: 588-590.

- Gennari F J, (1998) Hypokalemia. New England Journal of Medicine 339: 451-458.

- Halperin ML, Kamel KS, (1998)Potassium. The Lancet 352:135-140. Ellison DH, Terker AS (2015)Why your mother was right: how potassium intake reduces blood pressure. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc 126: 46-55.

- Enslow BT, Stockand JD,Berman JM (2019) Liddle’s syndrome mechanisms, diagnosis and management. Integr Blood Press Control 13-22.

- Lin SH, Lin YF, Chen DT, Chu P, Hsu CW, et al (2004) Laboratory tests to determine the cause of hypokalemia and paralysis. Arch Intern Med 164: 1561-1566.

- Matsunoshita N,Nozu K,Shono A, Nozu Y,Fu XJ, et al.(2016) Differential diagnosis of Bartter syndrome, Gitelman syndrome, and pseudo–Bartter/Gitelman syndrome based on clinical characteristics. Genetics in Medicine 18: 180-188. Touyz RM, de Baaij JHF, Hoenderop JGJ( 2024) Magnesium Disorders. New England Journal of Medicine 390: 1998-2009.

- Wu KL, Cheng CJ, Sung CC, Tseng MH, Hsu YJ, et al. (2017) Identification of the causes for chronic hypokalemia: importance of urinary sodium and chloride excretion. Am J Med 130, 846-855.

- Sterns RH, Cox M, Feig PU, Singer I (1981)Internal potassium balance and the control of the plasma potassium concentration. Medicine 60: 339-354.

- Cohn JN, Kowey PR, Whelton PK, Prisant LM (2000) New guidelines for potassium replacement in clinical practice: a contemporary review by the National Council on Potassium in Clinical Practice. Arch Intern Med 160: 2429-2436.

- Mancia G, Kreutz R, Brunström M, Burnier M, Grassi G, et al. (2023) ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension: Endorsed by the International Society of Hypertension (ISH) and the European Renal Association (ERA). J Hypertens 41: 1874-2071.

- Drew BJ, Califf RM, Funk M, Kaufman ES, Krucoff MW, et al.(2004) Practice standards for electrocardiographic monitoring in hospital settings: American Heart Association scientific statement from the Councils on Cardiovascular Nursing, Clinical Cardiology, and Cardiovascular Disease in the Young: endorsed by the International Society of Computerized Electrocardiology and the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Circulation 110: 2721-2746.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.