High-Grade B-Cell Lymphoma of the Right Maxillary Sinus: A Case Report

by Hassan El-Awour1*, Olesya Marushko2, Olena Marushko2, Jade Goodman1, Mohammed Inam Ullah Khan1

1Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

2Independent Researcher, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada

*Corresponding author: Hassan El-Awour, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Received Date: 19 January 2026

Accepted Date: 25 January 2026

Published Date: 28 January 2026

Citation: El-Awour H, Marushko O, Marushko O, Goodman J, Khan MIU (2026). High-Grade B-Cell Lymphoma of the Right Maxillary Sinus: A Case Report. Ann Case Report. 11: 2513. https://doi.org/10.29011/2574-7754.102513

Abstract

High-grade B-cell lymphoma (HGBCL) is a rare, aggressive cancer whose presentation in the maxilla is exceptionally uncommon and often mimics odontogenic disease. A 62-year-old female presented with an eight-month history of right maxillary swelling. Clinical examination revealed a firm vestibular mass from tooth 1.4 to 1.6, facial asymmetry, and loss of the nasolabial fold. Cone beam CT showed an ill-defined osteolytic lesion destroying the maxillary sinus walls and infraorbital canal, featuring periodontal ligament widening, root resorption, and a large soft tissue mass. Biopsy revealed sheets of atypical lymphoid cells. Immunohistochemistry was positive for CD20, PAX5, and BCL6. Fluorescence in situ hybridization confirmed MYC and BCL2 rearrangements, diagnosing HGBCL with these rearrangements (HGBCL-R). The patient was referred and started on R-CHOP chemotherapy. The case highlights that persistent unilateral swelling, unexplained dental findings like root resorption, and lesions unresponsive to treatment should raise suspicion for malignancy. Dental practitioners are critical for early recognition, and increased awareness can improve outcomes for this aggressive lymphoma.

Keywords: High-Grade B-Cell Lymphoma; Extranodal Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma; Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma; Maxillofacial Malignancy; Periodontal Ligament Widening.

Introduction

Lymphomas are a malignant disease of the lymphatic system, characterised by proliferation of lymphoid cells or their precursors [1]. Although quite rare, lymphomas rank third as the most common malignancy of the oral cavity [2]. Lymphomas are classified into two major categories: Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL) and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) [3]. In the head and neck region, NHL occurs more frequently than HL [2]. Approximately 40% of NHL cases involve extranodal sites including the stomach, liver, soft tissue, dura, bone, gastrointestinal tract and bone marrow [4]. Although the oral cavity is an uncommon site for NHL, representing only 2% of all extranodal lymphomas, there can be involvement of the Waldeyer’s tonsillar ring, the buccal mucosa, tongue, floor of the mouth, and retromolar area [3]. However, diagnosis of NHLs in the maxillary sinus is rare [5]. Moreover, the most common subtype of NHL is diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) characterized by B cell phenotype, diffuse growth pattern and an aggressive clinical history affecting individuals in their sixth decade of life. Most patients present with involvements on the gingiva or hard palate [2]. During early stages of malignant development, lymphomas can mimic common odontogenic and antral diseases both radiographically and clinically [6]. With revision of the WHO classification of lymphomas in 2016, a subtype of DLBCL called high-grade B-cell lymphoma (HGBCL) has been described. HGBCL comprises 2 types of lymphomas: HGBL with MYC and BCL2 and/or BCL6 rearrangements (HGBL, R) and high-grade B-cell lymphomas, not otherwise specified (HGBL, NOS) [7]. Specifically, HGBCL is a clinically aggressive type of B-cell NHL characterized by re-arrangements of either: 1) the MYC gene which encodes an oncogenic protein, leading to proliferation of immature B cells; or 2a) the BCL2 gene, which inhibits apoptosis, or 2b) less commonly, the BCL6 gene, a transcriptional repressor [8,9]. Given that HGBCL can mimic benign inflammatory diseases, there is often a delay in the correct diagnosis. Additionally, most patients present with rapidly enlarging masses, often with symptoms both locally and systemically [4]. This article presents a rare case of HGBCL involving the right maxillary sinus in an adult female in her sixth decade of life. It highlights the importance of a detailed evaluation of clinical signs and radiological findings during diagnosis.

Case Presentation

A 62-year-old Middle Eastern female presented to the dental office with the chief complaint of swelling on the buccal mucosa of the posterior right segment (Figure 1). Over the course of 8 months, the patient went to multiple dentists with the initial diagnosis of external root resorption of tooth 1.5 with treatment options including endodontic treatment. Upon clinical examination, the patient presented with persistent vestibulo-buccal swelling in the upper right posterior quadrant. The patient reported pain (Pain Rating Scale score of 6/10) that was initiated 8 months ago, intermittent in frequency, and not exaggerated by external factors. The patient’s health history included Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and hypertension. The patient’s social history included being a social drinker. There was no family history of cancer. The patient did not indicate any parafunctional habits such as clenching, bruxism, or sleep apnea. Currently, the patient is retired.

Figure 1: Clinical inspection revealed a small swelling in the buccal vestibule of the right maxillary posterior region.

Further clinical examination showed no lymphadenopathy extra-orally. However, the patient presented with facial asymmetry, ptosis of left lip, and loss of the right nasolabial fold (Figure 2). Trigeminal facial nerve was intact. The intra-oral examination conducted showed an exophytic, non-ulcerative, non-fluctuating, and firm soft tissue swelling in the vestibular region from tooth 14 to tooth 16 (3.5cm x 1.5cm). Clinical pulp tests indicated vital teeth. The teeth in the posterior right quadrant were free of carious lesions and deep restorations. No other dental or periodontal problems were detected clinically in the right maxillary posterior region.

Figure 2: Clinical examination revealing facial asymmetry, ptosis of the left lip, and an asymmetric nasolabial fold.

Initial Interpretation and Differential Diagnosis

Radiographic findings observed from the initial panoramic image (Figure 3) included: (1) minor signs of pathology with widening of the periodontal ligament space of the tooth 1.4 and tooth 1.5; and (2) root resorption of tooth 1.4 and tooth 1.5. The crowns, pulpal and root canals of the teeth in the posterior right maxilla were seemingly within normal limits. Given that widening of the periodontal ligament space of the maxillary premolars in the absence of dental disease suggests an etiology distinct from that tooth.

Figure 3: Cropped and enhanced panoramic radiograph demonstrating mild widening of the periodontal ligament space and root resorption of teeth 1.4 and 1.5.

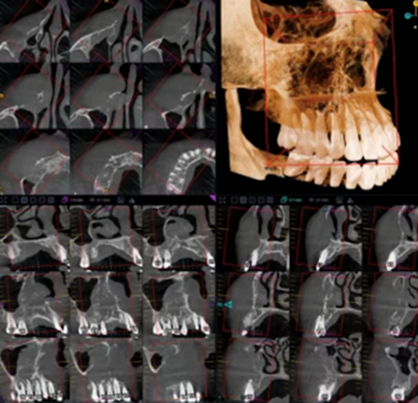

In case of a possible malignant neoplasm, the patient was referred for cone beam computed tomography of the maxilla and maxillary sinus (Figure 4). An ill-defined region of bone loss was located within the right maxilla, extending from site 1.6 to site 1.1 and from the crestal aspect of the alveolar process superiorly to involve the anterolateral wall of the right maxillary sinus, the right lateral nasal wall, as well as the right infraorbital canal. Radiographic findings further indicated a prominent, irregularly shaped widening of the periodontal ligament spaces around the roots of teeth 1.6, 1.5, 1.4, 1.3 and 1.2, and the interradicular bone between these teeth exhibited ill-defined osteolysis intermixed with irregularly shaped strands of sclerotic bone. Multiple ill-defined discontinuities were observed along the buccal cortex of the alveolar process overlying these areas, as well as the contiguous anterolateral wall of the maxillary sinus and lateral wall of the nasal fossa. Linear, spiculated strands of bone formation were evident emanating from the anterolateral surface of the right maxilla in a perpendicular orientation to the cortex. A large, dome-shaped soft tissue mass was evident extending from this cortical dehiscence extending anteriorly to the facial fat planes, into the interior nasal meatus anteriorly, and into the right antral space and infraorbital canal in the posterior direction.

Figure 4: Cone beam computed tomography showing an ill-defined osteolytic lesion in the right maxilla with cortical perforation and soft tissue extension, suggestive of malignancy.

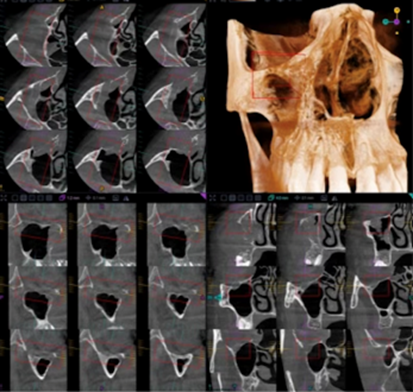

More specifically, these observations indicated a mass on the posterior-superior aspect that extended into the right infraorbital canal (Figure 5). Discontinuities were observed along the medial inferior walls of the anterior aspects of the canal. Moreover, the superior wall of the canal appeared elevated and thinned but not fully discernible radiographically. The overall diameter of the right infraorbital canal appeared abnormally enlarged, indicating possibility of perineural spread. These radiographic findings were suggestive of malignancy involving the right maxilla. Medical referral was indicated for further evaluation and management.

Figure 5: Cone beam computed tomography demonstrating suspected extension of the lesion into the right infraorbital canal.

The radiographic presentation necessitated consideration of several malignant processes in the differential diagnosis. Osteosarcoma was initially contemplated due to its potential for aggressive maxillofacial bone destruction; however, typical radiographic characteristics, such as mixed radiopaque-radiolucent appearances, osteoid matrix deposition, and prominent sunburst periosteal reactions were absent. Instead, the lesion demonstrated diffuse periodontal ligament widening, permeative osteolysis, cortical perforation, and extensive soft tissue extension, features more consistent with lymphoproliferative malignancies. The lack of mineralized matrix production further diminished the likelihood of osteosarcoma. Moreover, the unexplained enlargement of the infraorbital canal suggested possible perineural involvement, a finding that can accompany aggressive lymphomas. Collectively, the radiographic and clinical characteristics favored a diagnosis of a high-grade B-cell lymphoma, prompting an incisional biopsy to obtain definitive histopathological confirmation.

An incisional biopsy of the vestibular lesion was performed and submitted in 4% buffered formalin. Histopathological analysis demonstrated sheets of large atypical lymphoid cells with vesicular nuclei, prominent nucleoli, numerous mitotic figures, and apoptotic debris-findings consistent with high-grade B-cell lymphoma. Immunohistochemistry revealed strong positivity for CD20, PAX5, and BCL6, with a Ki-67 proliferation index exceeding 80%. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) testing identified MYC and BCL2 gene rearrangements, confirming the diagnosis of high-grade B-cell lymphoma with MYC and BCL2 rearrangements (HGBCL-R).

The patient was referred to medical oncology and commenced on standard systemic chemotherapy using the R-CHOP regimen (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone), the current standard of care for aggressive B-cell lymphomas. She remains under active treatment with ongoing clinical follow-up.

Discussion

HGBL is uncommon and data focusing on these neoplasms are rare. Few cases of DLBCL of the maxillary sinus have been reported and, to our knowledge, there are even fewer cases of HGBL of the maxillary sinus reported [5,10]. Malignancies of the maxillary sinus are often non-specific and mimic odontogenic infections [10]. Identifying whether the patient’s chief complaint is of odontogenic origin or nonodontogenic is critical but challenging given the similarity of symptoms of DLBCL of the maxillofacial region. As such, misdiagnosis is common [11]. Extranodal lymphomas of the maxillary alveolus first clinically present with swelling whereas pain or discomfort is less commonly noted, and numbness of the upper lip is reported in a quarter of NHL cases [12]. The patient had few complaints other than the clinically noted swelling and pain that first appeared with initial onset of swelling, and diagnosis was difficult to establish within the 8-month period symptoms.

NHL are often rapidly growing, infiltrating, and have a poor prognosis. A systematic review in 2017 indicated that NHLs have an overall prevalence in males, with recent reports indicating a higher prevalence in Africans, Middle Easterners, and East and South Asians [12]. Many patients are aware of their lesions for at least one month prior to presenting to a healthcare provider. Initially, the most common preliminary diagnosis is an odontogenic infection, cyst or followed by squamous cell carcinoma [4,12]. If the preliminary diagnosed inflammatory lesion does not respond promptly to treatment, clinicians must consider malignancy. Other symptoms of reported signs and symptoms of malignancies in the maxillary sinus include facial swelling, paresthesia, pain, failure of extraction socket to heal [10]. Given that extra-nodal lymphomas of the oral cavity carry a worse prognosis, dentists must be vigilant in their suspicion of malignancies. In this case, a history of pain or swelling of unknown origin, unexplained widening of periodontal ligament space, and unexplained resorption must be considered a warning sign to the dentist.

Conclusion

The availability of data on the diagnosis, pathogenesis, and clinical behaviour of HGBL, especially NHL in the maxillary sinus, is currently limited [5]. It is well accepted that NHLs have a varied manner of presentation, response to therapy and prognosis [12]. Both clinically and radiographically, the manifestation of NHLs can mimic malignant diseases such as squamous cell carcinoma, odontogenic cysts or tumours, or infections [10]. This case specifically highlights how dentists can play a part in early detection of the malignancy. Specifically, if there is a unilateral swelling, with limited suspicions of inflammatory disease, or if the preliminary diagnosed inflammatory lesion does not respond to treatment, dentists must consider malignancy.

Declarations

Contributors: All authors contributed to planning, literature review and conduct of the case report. All authors have reviewed and agreed on the final manuscript.

Competing interests: None

Patient consent for publication: Informed consent was obtained from the patient, consent form available upon request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate: Not applicable

Availability of data and materials: Not applicable

Funding: No Funding

References

- Silva TD, Ferreira CB, Leite GB, Menezes Pontes JR de, Antunes HS. (2016). Oral manifestations of lymphoma: a systematic review. Ecancermedicalscience. 10: 665.

- Janardhanan M, Suresh R, Savithri V, Veeraraghavan R. (2019). Extranodal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of maxillary sinus presenting as a palatal ulcer. BMJ Case Reports. 12: 228605.

- Zou H, Yang H, Zou Y, Lei L, Song L. (2018). Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the maxilla: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 97: 10707.

- Adwani DG, Arora RS, Bhattacharya A, Bhagat B. (2013). Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of maxillary sinus: an unusual presentation. Annals of Maxillofacial Surgery. 3: 95-97.

- Brody A, Dobo-Nagy C, Mensch K, Oltyan Z, Csomor J, et al. (2021). High-grade B-cell lymphoma not otherwise specified (HGBL, NOS) in the maxillary sinus mimicking periapical inflammation: case report and review of the literature. Applied Sciences. 11: 8803.

- Yepes JF, Mozaffari E, Ruprecht A. (2006). B-cell lymphoma of the maxillary sinus. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontology. 102: 792-795.

- Li J, Liu X, Yao Z, Zhang M. (2020). High-grade B-cell lymphomas, not otherwise specified: a study of 41 cases. Cancer Management and Research. 12: 1903-1912.

- Ok CY, Medeiros LJ. (2020). High-grade B-cell lymphoma: a term re-purposed in the revised WHO classification. Pathology. 52: 68-77.

- National Lymphoma Foundation (n.d.) About lymphoma. National Lymphoma Foundation. Retrived from online.

- Gill DS, Cunliffe D, Ali A, Sternberg A. (2000). Malignant lymphoma of the maxillary sinus masquerading as an odontogenic infection: report of a case. Dental Update. 27: 132.

- Cui J, Zhang S, He H. (2022). Primary extra nodal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the maxillary sinus with symptoms of acute pulpitis. Case Reports in Dentistry. 2022: 8875832.

- MacDonald D, Lim S. (2018). Extranodal lymphoma arising within the maxillary alveolus: a systematic review. Oral Radiology. 34: 113-126.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.