Hepatitis B and C Profile in Diabetics

by Tariam Djibangar Agnès1*, Adama Ahmed N’Garé2*, Bilal Mahamat3, Abdelaziz Abdelkerim3, Ousman Fager Malick1, Nonhoungar Rodrigue1, Doudje Kondy1, Bessimbaye Nadlaou3, Abdelsalam Tidjani3

1Department of Immunology and Internal Medicine at the National Reference Hospital Center (CHU-RN)

2Department of Internal Medicine and Gastroenterology, CHU La Référence Nationale of N'Djamena (Chad)

3Faculty of Human Health Sciences (FSSH)

*Corresponding authors: Tariam Djibangar Agnès, Department of Immunology and Internal Medicine at the National Reference Hospital Center (CHU-RN).

Adama Ahmed N’Garé, Department of Internal Medicine and Gastroenterology, CHU La Référence Nationale of N'Djamena (Chad).

Received Date: 13 November 2024

Accepted Date: 18 November 2024

Published Date: 25 November 2024

Citation: Agnès TD, N’Garé AA, Mahamat B, Abdelkerim A, Malick OF, et al. (2024) Hepatitis B and C Profile in Diabetics. Infect Dis Diag Treat 8: 269. https://doi.org/10.29011/2577-1515.100269.

Abstract

Introduction: Viral hepatitis is an inflammatory liver disease transmitted orally, fecally, through blood, parenterally, or sexually, characterized by damage to the liver parenchyma, which can originate from viral infection. The latest estimates from the International Diabetes Federation indicate that 8.3% of adults (382 million people) are affected by hepatitis, and the number of people affected is expected to exceed 592 million within the next 25 years. What is the prevalence of hepatitis B and C infections among diabetics in sub-Saharan Africa, particularly in Chad? This study aims to contribute to the management of hepatitis B and C in diabetics. Materials and Methods: This was a cross-sectional analytical study conducted over a 3-month period from January to April 2024. The rapid test technique for Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and anti-HCV antibodies was used in diabetic patients. Results: A total of 150 cases were analyzed. Patients were aged between 18 and 85 years, with an average age of 49 ± 49 years. Women were more represented in the sample, with a frequency of 66.67%. Type 2 diabetes was more common than type 1, at 92.67% and 7.33%, respectively. HBsAg was positive in 7 patients, representing a frequency of 4.67%, and anti-HCV antibodies were positive in 2 patients, or 1.33%. Most positive cases were found among women with type 2 diabetes. The study showed a predominance of infection among married individuals, accounting for 77.77%. Among the various districts, HBV seroprevalence was highest in the 8th district, while HCV prevalence was higher in the 6th and 8th districts. Conclusion: The prevalence of hepatitis B and C varies by country, depending on risk factors affecting diabetic patients.

Keywords: Hepatitis B; Hepatitis C; Diabetes; Prevalence; CHU-RN

Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) represents a major cause of acute and chronic liver diseases worldwide, such as cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 2 billion people have been exposed to this virus, or approximately one in three individuals, with 10 to 30 million new infections annually. The number of chronic carriers is estimated at over 350 million, with nearly one million deaths each year [1,2].

Globally, the HBV prevalence rate is approximately 5.4%, compared to 3% for Hepatitis C [3].

The hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection represents a significant public health issue, being one of the most common causes of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated the global prevalence of HCV infection at 3%, which represents approximately 170 million people affected.

In North Africa, seroprevalence is moderate in Maghreb countries; however, in Egypt, HCV prevalence is very high, sometimes exceeding 15% [4].

As for hepatitis B, it remains a major public health concern worldwide, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, where certain regions exhibit high endemicity [5,6]. Chronic HCV infection is associated with an increased incidence of insulin resistance and diabetes mellitus. Depending on the severity of liver damage, it is estimated that between 10% and 30% of patients with chronic HCV infection have diabetes. The risk increases with the degree of liver fibrosis [7]. Diabetics are more susceptible to multiple infections, whether viral or bacterial, due to weakened immune defenses and poor hygiene.

Hepatitis B infection is rarely screened for in diabetics, as most researchers tend to focus on HCV. Several studies conducted worldwide on hepatitis B and C prevalence show variability, ranging from 1.63% to 20% for hepatitis B [8,9] and 0% to 27.38% for hepatitis C [10].

What is the prevalence of hepatitis B and C infection among diabetics in sub-Saharan Africa, particularly in Chad? This study aims to contribute to the management of hepatitis B and C among diabetics.

Methods

Type and Study Location

This was a cross-sectional analytical study conducted over a 3-month period from February to April 2024. The National Reference Hospital University Center of N'Djamena (CHU-RN) served as the study setting. Patients were recruited within the diabetology department based on a survey form. Informed consent from patients or their guardians was obtained prior to recruitment.

Study Population

The study population comprised 150 diabetic patients of both sexes, aged 18 to 85, who were received in the diabetology department at CHU-RN in N'Djamena and diagnosed with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes. Sociodemographic and biological data were collected using a pre-established form.

Blood Collection

Blood samples were drawn by peripheral vein puncture in a red tube for the assay of anti-HBs and anti-HCV antibodies.

Data Collection Techniques and Tools

To collect data, the purpose of the study was explained to each patient, followed by a direct interview. Specific and clear questions were asked, and a pre-prepared data sheet was used.

Testing Technique (Strip Test)

We used two tests for each patient (HBV and HCV): Rapid test cassettes for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and rapid test cassettes for anti-HCV antibodies (hepatitis C).

Procedure

After cleaning the patient’s finger with an alcohol-soaked cotton pad, a slight prick was made with a lancet. Using a dropper, we took 10 microliters of whole blood and placed it in the sample well (S) of the test cassette, then added 2 drops of reagent and started the timer. The colored line(s) appeared after 5 minutes.

Reading and Interpretation of Results

POSITIVE: Two colored lines appear. One colored line must be in the control area (C) and another in the test area (T).

NEGATIVE: One colored line appears in the control area (C), and no colored line appears in the test area (T).

INVALID: No control line appears. An insufficient sample volume or procedural error are the most likely reasons for the lack of a control line. The procedure is reviewed, and the test is repeated with a new cassette. If the issue persists, we immediately discontinue use of the test kit and contact our local distributor.

Statistical Analysis

Data entry and analysis were performed using Microsoft Excel software.

Ethical Considerations

The survey was conducted following the informed and written consent of patients. The anonymity of survey responses and confidentiality of obtained information were ensured.

Results

Sociodemographic and Biological Characteristics:

A total of 150 diabetic patients of both sexes were included in the study.

Sociodemographic Characteristics

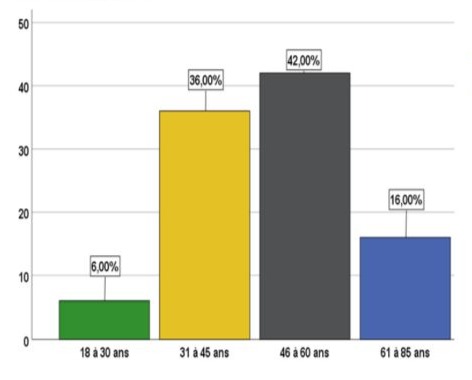

Age

Patients aged 46 to 60 were the most represented. The average age was 49.49 years, with a standard deviation of 12.13. The range was from 18 to 80 years.

Figure 1: Distribution of diabetic patients by age group.

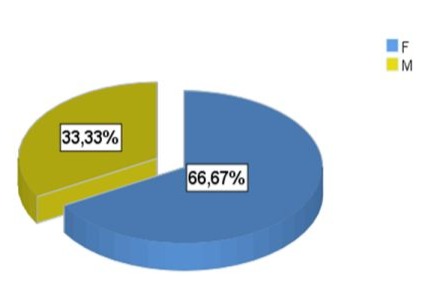

Gender

Females were the most represented, accounting for 66.67% (n=100), with a gender ratio of 2.

Figure 2: Distribution of diabetic patients by gender.

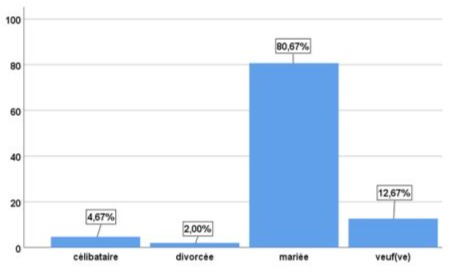

Marital Status

Most patients were married, representing 80.67%.

Figure 3: Distribution of diabetic patients by marital status.

Biological Characteristics of Patients

Distribution of Patients by Diabetes Type

Type 2 diabetes was the most common, accounting for 92.67%.

|

diabetes type |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Type 1 |

11 |

7,3 |

|

Type 2 |

139 |

92,7 |

|

Total |

150 |

100,0 |

Table 1: Distribution of patients by diabetes type.

Risk Factors

|

Risks |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

ATCD familial |

20 |

13,33% |

|

Surgical Intervention |

58 |

38,66% |

|

Hospitalisation |

62 |

41,33% |

|

Blood Transfusion |

10 |

6,33% |

|

TOTAL |

150 |

100% |

Table 2: Distribution of diabetic patients by risk factors.

Research on various antecedents (ATCD family history of viral hepatitis, blood transfusions, surgeries, hospitalizations) showed that most diabetic patients in this study had a history of hospitalization, with 41.33%.

Prevalence of Hepatitis B and C

During the study period, 150 patients underwent serological testing. The results are shown below:

|

Ag HBS |

Frequence |

Percentage |

|

Negative |

143 |

95,3 |

|

Positive |

7 |

4,7 |

|

Total |

150 |

100,0 |

|

Ac HCV |

Frequence |

Percentage |

|

Negative |

148 |

98,7 |

|

Positive |

2 |

1,3 |

|

Total |

150 |

100,0 |

Table 3: Frequency of hepatitis B and C.

The HBS antigen was positive in 7 patients, representing a frequency of 4.67%, and anti-HCV antibodies were positive in 2 patients, or 1.33%.

Discussion

We conducted a cross-sectional analytical study over a three-month period on the profile of hepatitis B and C infection among diabetic patients at the National Referral University Hospital (CHU_RN) in N'Djamena. We examined 150 diabetic patients aged 18 to 85, with an average age of 49.49 years and a standard deviation of 12.31. Women were more represented in the study sample, with a frequency of 66.67%, resulting in a gender ratio of 2. Overall, Type 2 diabetes was more prevalent compared to Type 1, accounting for 92.67% and 7.33%, respectively.

Diabetes and hepatitis virus infection (HCV and HBV) are currently public health issues. Hepatitis B infection is rarely investigated among diabetics, as most researchers focus on hepatitis C. During this study, serological testing for hepatitis B and C was conducted in the diabetology department to detect anti-HCV antibodies and HBS antigens. AgHBS was positive in 7 patients with a frequency of 4.67%, and anti-HCV was positive in 2, or 1.33%. Studies conducted in different regions of the world in the search for hepatitis B and C, including in Morocco [11], Italy [17], Turkey [8,12], and Taiwan [9], reported higher seropositivity rates.

Several factors could contribute to the low prevalence of hepatitis B and C infection observed. Hepatitis B surface antigens may not be detectable during the incubation phase if the viral load has not reached a detectable threshold. Hepatitis B progresses through multiple stages, with a seroconversion phase lasting 2 to 8 weeks, explaining seronegativity in some patients, at the end of which anti-HBS antibodies appear and AgHBS disappears during convalescence [13,14]. False negatives may occur, especially for HBV, if the patient's antibody is bound to viral antigens in immune complexes, preventing antibody detection. Additionally, low prevalence may be due to failure to identify infected patients due to the serological window.

Moreover, anti-HCV antibodies appear around the sixth week after infection. The anti-HCV antibody test has a high predictive value for identifying hepatitis C exposure but may miss patients who have not yet developed antibodies (seroconversion) or have an insufficient antibody level for detection during this period. Serology may also be negative in immunocompromised patients, such as those who are HIV-positive. Some individuals infected with HCV may never develop antibodies against the virus, resulting in a permanently negative test for anti-HCV antibodies [15].

Evaluating AgHBS prevalence by demographic characteristics in diabetic patients showed that seropositive patients were predominantly female. This result was higher than in other studies, such as Mekonnen et al. [16], Soverini et al. [17], and Gulcan et al. [12], which reported female predominance with sex ratios of 0, 0.85, and 0.68, respectively, possibly due to females' increased vulnerability to infections due to their reproductive systems. The average age of seropositive patients was 52 years, lower than in studies by Soverini et al. [17], Sangiorgio et al. [18], and Gulcan et al. [12], which reported average ages of 62.4, 62.23, and 59.8, respectively. Most infected patients were married, with a predominance of 77.77%. The high infection rate among married individuals may be due to infidelity within the couple.

In the various districts, the seroprevalence of HBV was higher in the 8th district, which could be explained by the population congestion in these areas. All seropositive patients were type 2 diabetics. This result was consistent with the studies by Soverini et al. [17] and Mekonnen et al. [16], who reported a higher frequency by analyzing samples from type 2 patients only. This could be explained by the fact that type 2 diabetics are more susceptible to hepatitis infection.

The risk factors for most seropositive patients included a family history of viral hepatitis, hospitalization, surgery, and blood transfusion. The potential sources of HBV contamination were surgeries and hospitalizations, which might be due to the lack of sterilization of surgical equipment and poor practices during hospitalization.

Conclusion

Diabetes and hepatitis C and B infections constitute serious public health issues. A relationship between these three conditions has been discussed by several research teams in the literature. However, the risk factors for this association are not yet fully understood. The frequency of hepatitis B and C varies from one country to another, depending on risk factors affecting diabetic patients. In our study, the prevalence was 4.67% for HBsAg and 1.33% for anti-HCV antibodies at the National Reference University Hospital.

In light of these results, systematic screening should be conducted for diabetic patients, and preventive measures like prophylaxis could help reduce the risk of HBV and HCV infections.

References

- Muszlack M, Lartigau-Roussin C, Farthouat L, Petinelli M, Hebert JC, et al. (2007) Vaccination of children against hepatitis B in Mayotte, a French island of the Comoros. Arch Pediatr 14:1132-1136.

- Tiollais P, Chen Z (2010) The hepatitis B. Pathol Biol 58:243-244.

- Brislot Myers S. Hepatitis B: better understanding for better treatment. J Pediatr Pueric 2006; 19: 340-3.

- Soussan P et al. Hepatitis C virus. EMC (Elsevier Masson SAS, Paris), Clinical Biology 2010; 90-55.

- Appit, Viruses Hepatitis. In: APPIT, ed. E Pilly, Montmorency: 2M2 Ed; 997: 346-359.

- Larousse B. Current data on viral hepatitis, Claude Bernard Hospital Days, Paris, 1986, ARNETTE ed, 1985, 162 p.

- Francesco N, Seirafi M. Hepatitis C and insulin resistance. Swiss Medicine. 2008.

- Demir M, Serin E, Göktürk S, Ozturk Na, Kulaksizoglu S, et al. (2008) The prevalence of occult hepatitis B virus infection in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 20:668-673.

- Chen H, Chung-Yi L, Chen P, See T, Lee H (2006) Seroprevalence of Hepatitis B and C in Type 2 Diabetic Patients. J Chin Med Assoc 69:146-152.

- Greca LF, Pinto LC, Rados DR, Canani LH, Gross JL (2012) Clinical features of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and hepatitis C infection. Braz J Med Biol Res 45:284-290.

- Nassifa B (2014) Thesis: Seroprevalence of hepatitis C infection in type 2 diabetics. Morocco: Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy.

- Gulcan A, Gulcan E, Toker A, Bulut I, Akcan Y (2008) Evaluation of risk factors and seroprevalence of hepatitis B and C in diabetic patients. J Investig Med 56:858-863.

- Soussan P, Le Pendeven C (2005) Challenges in interpreting virological diagnostics of hepatitis B. French Laboratory Journal. Feb 2005.

- Marcellin P, Asselah T, Boyer N (2005) Chronic Hepatitis B Treatment, Revu Prat, 2005.

- Djelti F. Thesis: Viral hepatitis B and C. Tlemcen: CHU Tlemcen, Infectious Diseases Department, 2011-2012. p. 26-38.

- Mekonnen D, Gebre-Selassie S, Fantaw S, Hunegnaw A, Mihre A (2014) Prevalence of hepatitis B virus in patients with diabetes mellitus: a comparative cross sectional study at Woldiya General Hospital, Ethiopia. Pan Afr Med J 17:40.

- Soverini V, Persico M, Bugianesi E, Forlani G, Salamone F, et al. (2011) HBV and HCV infection in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a survey in three diabetes units in different Italian areas. Acta Diabetol 48:337-343.

- Sangiorgio L, Attardo T, Gangemi R, Rubino C, Barone M, et al. (2000) Increased frequency of HCV and HBV infection in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 48:147-151.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.