Hard Palate Perforation and Prosthetic Rehabilitation in Cocaine Abuser: A Case Report

by Vincenzo Grieco, Gaya Guerrera*, Luca Raffaelli

Department of Surgical sciences for head and neck diseases, School of dentistry, Catholic University of Sacred Heart, Largo A. Gemelli, Rome, Italy

*Corresponding author: Gaya Guerrera, Department of Surgical sciences for head and neck diseases, School of dentistry, Catholic University of Sacred Heart, Largo A. Gemelli, 1, 00168, Rome, Italy

Received Date: 14 April 2025

Accepted Date: 17 April 2025

Published Date: 21 April 2025

Citation: Grieco V, Guerrera G, Raffaelli L (2025) Hard Palate Perforation and Prosthetic Rehabilitation in Cocaine Abuser: A Case Report. Ann Case Report. 10: 2263. https://doi.org/10.29011/2574-7754.102263

Abstract

Cocaine is a psychoactive substance commonly consumed through inhalation. Chronic direct contact with the mucous membranes causes localized damage, leading to vasoconstriction and inducing ischemia and necrosis of soft tissues, eventually causing erosion and perforation of the nasal septum and palate. Dentists should recognize the signs of cocaine abuse and the degenerative progression of the affected tissues in order to identify them early. Furthermore, they should be capable of managing the rehabilitative stages and techniques to restore the patient’s phonetics and swallowing, pending more invasive reconstructive surgical interventions. This case report describes a case of cocaine abuse with palatal perforation and rehabilitation using an obturator prosthesis.

Keywords: Cocaine; Palate; Perforation; Obturator; Prosthesis; Prosthetic.

Introduction

Cocaine has a powerful vasoconstrictive effect that reduces blood flow, causes spasms, arteriosclerosis, and localized thrombosis, leading to tissue ischemia. Among the early signs of repeated inhalation of the substance is chronic rhinitis, which manifests as nasal congestion, discharge, sneezing, and itching signs of irritation of the nasal structures. The olfactory receptors may also be damaged, causing anosmia [1].

Tissue ischemia and the resulting inflammation can lead to the development of ulcers, which, in the short term, vary in size, coalescing and causing erosion and perforation of the nasal septum and palate [2]. Moreover, cocaine use can weaken the immune system, making the nose more susceptible to bacterial or fungal infections. The reduced healing capacity of the damaged tissues promotes the progressive deterioration of the nasal and palatal structures, with severe aesthetic and functional implications, compromising swallowing and speech. Stabilization of this condition is guaranteed only by abstaining from drug use. Even reconstructive surgical interventions may not be definitive, as they do not exclude recurrences if cocaine abuse continues over time.

Palatal perforations can also be induced by the inhalation of substances used for therapeutic purposes, such as desmopressin, or by cutting agents used to prolong the effects of the drug, such as acetylsalicylic acid or levamisole [3], which is employed in the treatment of sarcoidosis. The DEA (Drug Enforcement Administration) has stated that levamisole has been found in about 80 per cent of seized cocaine [4].

In some cases, the appearance of lesions caused by drug abuse can mimic the signs of other diseases (infectious, neoplastic, autoimmune) [5]. Specifically, the appearance of Cocaine-Induced Midline Destructive Lesions (CIMDL) can be confused with that caused by nasal lymphomas [6] and Wegener’s Granulomatosis [7].

Case Presentation

A 37-year-old patient presents for an outpatient visit at the Department of Dentistry and Prosthodontics at the A. Gemelli University Polyclinic, complaining of difficulty in eating and speaking due to a markedly nasal voice register. The medical history reveals the onset of a palatal lesion that started as a small perforation at the level of the left transverse palatal suture. It progressed slowly and progressively, eventually involving the soft palate, then suddenly deteriorated, leading to the destruction of the velum in just two weeks. The patient reports abusing cocaine for about seven years. No further significant information is revealed.

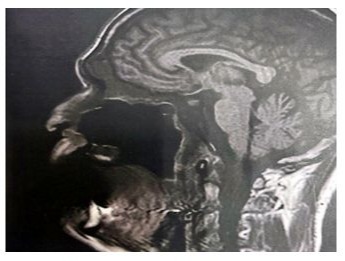

On intraoral examination, a palatal perforation is observed, affecting the palatal processes of the left maxilla, the visible nasal septum, the collapse of the columella, and a posterior extension involving the soft palate, with destruction of the velum. There is evidence of bleeding, mucopurulent secretions, and fetor ex ore. The dentition is complete, although the teeth in the upper left quadrant show severe mobility due to involvement of the alveolar process, with no exposure of necrotic bone (Figure 2). The objective examination is complemented by the magnetic resonance imaging, which was requested by the colleagues from the Maxillofacial Surgery department and provided by the patient for evaluation (Figure 1).

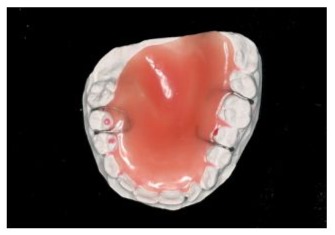

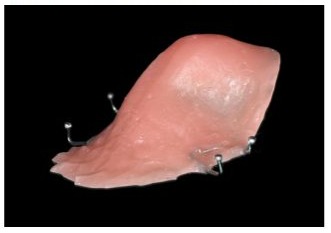

The patient already wears an obturator prosthesis, which is now ill-fitting due to the progression of the oro-nasal communication (Figure 2,3).

Figure 1: Sagittal RMI image.

Figure 2: First dental appointment: Oro-nasal communication.

Figure 3: Oro-nasal communication evolution, a month later.

Treatment

Treatment planning

The closure of the oro-nasal communication requires a multidisciplinary approach. The creation of a temporary obturator prosthesis improves the patient’s quality of life and allows them to begin a rehabilitation process for substance abuse, pending a definitive resolution. The diagnostic and planning process include the following stages:

- A consultation with the Infectious Diseases Department is requested to exclude infectious etiology or any concomitant risk factors [8].

- Toxicological tests are requested to determine metabolites, initiating an 18-month period during which the patient must cease substance use in order to resolve the vasculitis [9] underlying the perforations and improve the prognosis for reconstructive surgery.

- A joint assessment is made with the Maxillofacial Surgery Department to evaluate the compromise of soft tissues, review the second-level radiological exams (Fig.1), and plan for a future surgical intervention.

- Photographic documentation is collected to monitor the progression of the lesion (Figure 2,3).

Creation of the obturator prosthesis

- The oro-nasal communication is covered with a gauze to prevent excessive penetration of the impression material into the nasal cavities. A first impression is taken using low-viscosity alginate to obtain a starting hard resin plate, which will serve as the base for the obturator prosthesis.

- Direct relining of the starting resin plate with self-curing resin.

- Second impression with alginate, securing the plate.

- Second cold relining in the distal area, aiming to achieve the proper fit.

- Refining and polishing in the laboratory.

- Delivery of the functional prosthesis (Figure 4, 5).

Figure 4: Prosthetic margins - occlusal photo.

Figure 5: Prosthetic delivery - lateral photo.

Discussion

The creation of a prosthetic device in patients with large oro-nasal perforations requires integrating clinical evaluation with second-level radiographic exams. A CT scan of the facial bones allowed for the adoption of precautions to reduce the risk of iatrogenic damage to the tissues during the impression-taking process, preventing the creation of a device with incongruent dimensions that could accelerate the progression of the perforation. A low-viscosity impression material was chosen instead of a standard-viscosity one to reduce the risk of changes or collapse of the palate and remaining structures, which are under pressure during this procedure.

The mobility of the teeth in the upper left quadrant, with total or partial loss of bone support, made it more difficult to record the dental impression, which was performed using the traditional technique, as the use of intraoral scanners still faces limitations in reading surfaces that are so deep.

Conclusion

The obturator prosthesis created has significantly improved the patient's quality of life, providing them with a device that supports them through the process from detoxification to surgical intervention. The relining in the posterior areas allowed for the creation of a seal at the posdam, enabling the performance of basic daily functions.

Proper swallowing has been restored, and the phenomenon of dyslalia has been significantly reduced.

Declarations

Contributors: All authors contributed to planning, literature review and conduct of the review article. All authors have reviewed and agreed on the final manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate: Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials: Not applicable.

Funding: No Funding.

References

- Bauer, L. O, & Mott A. E. (1996). Differential effects of cocaine, alcohol, and nicotine dependence on olfactory evoked potentials. Drug and alcohol dependence, 42: 21-26.

- Trimarchi, M, Nicolai, P, Lombardi, D, Facchetti, F, Morassi, M. L, et al (2003). Sinonasal osteocartilaginous necrosis in cocaine abusers: experience in 25 patients. American journal of rhinology, 17: 33-43.

- Formeister, E. J, Falcone, M. T, & Mair, E. A. (2015). Facial cutaneous necrosis associated with suspected levamisole toxicity from tainted cocaine abuse. Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology, 124: 30-34.

- Tallarida, C. S, Egan, E, Alejo, G. D, Raffa, R, Tallarida, R. J, et al (2014). Levamisole and cocaine synergism: a prevalent adulterant enhance cocaine's action in vivo. Neuropharmacology, 79: 590-595.

- Seyer, B. A, Grist, W, & Muller, S. (2002). Aggressive destructive midfacial lesion from cocaine abuse. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontology, 94: 465-470.

- Kwong, Y. L, Chan, A. C, & Liang, R. H. (1997). Natural killer cell lymphoma/leukemia: pathology and treatment. Hematological oncology, 15: 71-79.

- Nico, M. M. S, Pinto, N. T, & Lourenço, S. V. (2020). From strawberry gingivitis to palatal perforation: The clinicopathological spectrum of oral mucosal lesions in granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine, 49: 443-449.

- Murthy, V, Vaithilingam, Y, Livingstone, D, & Pillai, A. (2014). Prosthetic rehabilitation of palatal perforation in a patient with ‘syphilis: the great imitator’. Case Reports, 2014: bcr2014204259.

- Berman, M, Paran, D, & Elkayam, O. (2016). Cocaine-Induced Vasculitis. Rambam Maimonides medical journal, 7: e0036.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.