Glucocorticoid Therapy and Flare Risk in Psoriatic Arthritis: A Real-World Observational Cohort Study

by Shahad Saleh Mohammed Almusawi1,2*, Magdalena Teresa Zubowic1,2, Stavros Chrysidis1,2, Oliver Hendricks1,2, Philip Rask Lage-Hansen1,2

1Department of Internal Medicine, Esbjerg Hospital - University Hospital of Southern Denmark, Denmark.

2Department of Regional Health Research, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark

*Corresponding author: Shahad Saleh Mohammed Almusawi, Department of Internal Medicine, Section of Rheumatology, Esbjerg Hospital - University Hospital of Southern Denmark, Esbjerg, Denmark.

Received Date: 12 December, 2025

Accepted Date: 22 December, 2025

Published Date: 26 December, 2025

Citation: Almusawi SSM, Zubowic MT, Chrysidis S, Hendricks O, Lage-Hansen PR (2025) Glucocorticoid Therapy and Flare Risk in Psoriatic Arthritis: A Real-World Observational Cohort Study. J Orthop Res Ther 10: 1411. https://doi.org/10.29011/2575-8241.001411

Abstract

Objective: To examine the association between systemic glucocorticoid (GC) use and psoriasis flares in patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) in a real-world clinical setting. Methods: We conducted a single-centre retrospective observational cohort study at Esbjerg University Hospital, Denmark. Adults meeting CASPAR criteria for PsA were identified through electronic medical records and interviewed via structured telephone surveys. GC exposure (oral, intramuscular, or intra-articular) in the preceding year and patient-reported psoriasis flares were recorded. Primary outcome was flare occurrence within 4 weeks of GC administration. Secondary analyses assessed 1-year flare risk and associations by GC administration route. Group differences were evaluated using chi-square tests and multivariable logistic regression. Results: Of 343 screened patients, 208 were included; 90 (43%) had received GCs in the past year. Within 4 weeks of GC use, flares occurred in 5 patients (6%), all after intra-articular injections. Over 1 year, flare rates were 63.3% in GC-treated vs. 47% in non-GC patients (absolute risk difference 15.9%, p = 0.0326; adjusted OR 2.15, 95% CI 1.19–3.95). Intra-articular administration was the only route significantly associated with flares (p = 0.0173). Conclusion: Short-term psoriasis flares following GC therapy were uncommon and largely confined to intra-articular administration. The elevated 1-year flare rate in GC-treated patients likely reflects confounding by indication rather than a direct pharmacologic effect. These findings challenge the historical perception of high flare risk with systemic GCs in PsA and support further prospective studies with standardized flare assessment, detailed GC exposure data, and robust control for disease activity.

Introduction

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic inflammatory rheumatic disease characterised by heterogeneous involvement of peripheral joints, axial skeleton, skin, nails, and entheses [1,2]. The disease is frequently accompanied by comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome, adding to its clinical complexity [3-7].

Management remains challenging due to the disease’s variable course and the need for therapies targeting both joint and skin manifestations [5]. A treat-to-target strategy is recommended to optimize outcomes and prevent structural damage and typically includes a combination of conventional synthetic diseasemodifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs), biologics, and targeted synthetic therapies, with treatment tailored to individual domains of involvement [2,8].

Systemic glucocorticoids (GCs) have historically been avoided in PsA and psoriasis due to concerns over triggering cutaneous flares, including severe forms such as pustular or erythrodermic psoriasis, but this caution originates largely from early anecdotal reports and case series [9-11], and is reflected in treatment guidelines which discourage the use of systemic GCs in psoriasis and PsA unless it is interpreted without alternative [2]. However, GCs are regularly used in clinical practice for PsA patients, particularly during acute flares or as a bridging strategy when initiating csDMARDs [12].

Recent evidence challenges the assumption that systemic GCs are strongly associated with psoriasis flares. For example, a large retrospective study by Gregoire et al. found a low incidence of psoriasis flares (1.42%) following systemic GC use in patients with a history of psoriasis, with only one severe flare recorded in over 500 patients [13].

Vincken et al. conducted a systematic review examining the safety of systemic GC use in both psoriasis and PsA [14]. While the review concluded that psoriatic flares were rarely reported, the authors noted that among the PsA-specific studies included (n=5), only one directly reported on skin flare outcomes [11,1517]. This highlights a major evidence gap: despite frequent GC use in PsA patients, high-quality data specifically addressing the risk of psoriasis flares in PsA populations remains scarce and inconclusive.

There is a need for focused investigation into these common treatment situations. A more precise risk analysis of short-term GC therapy is expected to have significant impact on clinical decision-making. In the present study, we report the largest realworld dataset to date examining the association between systemic glucocorticoid use and the risk of psoriasis flares in individuals with PsA.

Methods

Study Design

This is a single-center retrospective observational cohort analysis conducted at the Department of Rheumatology, Esbjerg University Hospital, Denmark.

Settings and Participants

All patients diagnosed with PsA treated at an outpatient clinic were identified through the electronic medical records system in November 2023. Medical records were reviewed, and if the PsA diagnosis were verified, patients were subsequently contacted via telephone and invited to participate. Before categorizing them as unreachable, up to five contact attempts were made per patient. During structured telephone interviews, patients were asked to recall whether they had experienced any flares of psoriatic skin lesions within the past year. For those who had received GC therapy within the preceding year and reported psoriatic flares, additional information was collected regarding the occurrence of flares within four weeks following the GC administration.

Furthermore, participants were asked to describe any perceived positive or negative effects of GC treatment, irrespective of the route of administration. The study was approved by the local scientific authorities in the region of Southern Denmark (approval number 23/50845).

Data Sources and Variables

Data were collected from medical records and telephone interviews, and included the following variables: age, sex, height, weight, PsA treatment during the observational period, concomitant medications, use of glucocorticoids (GCs) within the past year (via oral, intramuscular, or intra-articular administration), patientreported occurrence of psoriatic flares within the past year, and any occurrence of psoriatic flares within four weeks following GC administration.

Study Size

This is an observational study of all accessible PsA patients from the outpatient clinic of the department of rheumatology at Esbjerg University Hospital. Thus, no formal study size calculations were performed.

Statistics

Categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables were described by means and standard deviations (SDs). Baseline group differences were assessed using standardised differences, which offer a sample size– independent measure of imbalance. Unlike p-values, standardized differences quantify the magnitude of group differences in standard deviation units, facilitating consistent interpretation across variables. A standardized difference <0.1 suggests negligible imbalance, whereas values >0.8 indicate substantial differences. Additionally, absolute mean differences with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported to provide interpretable effect sizes in original measurement units, with CIs indicating the precision of estimates.

Associations between GC therapy and psoriasis flare were tested using chi-square analysis on 2×2 contingency tables, with significance defined as p < 0.05. Chi-square tests were also used to evaluate differences in psoriasis flare risk by GC administration route. Finally, logistic regression was conducted to identify baseline predictors of psoriasis skin flare. All statistical analyses were conducted using the R 4.4.2 software.

Results

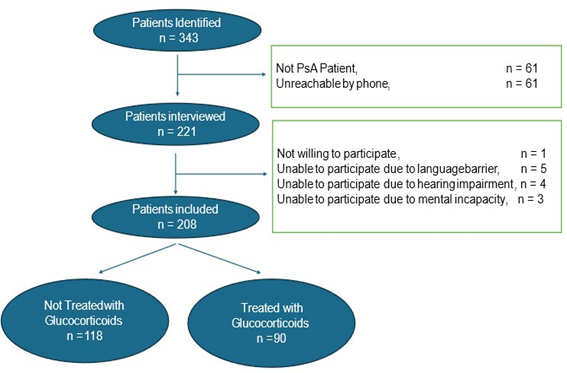

A total of 343 potential PsA patients were identified through the electronic medical records system. Of these, 61 patients did not meet the Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR)

(21) and were therefore excluded. An additional 61 patients could

not be reached despite multiple contact attempts, resulting in 221 eligible patients for interview. Among these, 208 patients consented to and successfully completed the interview. Within this cohort, glucocorticoid treatment during the observation period was documented in 90 patients, according to the electronic medical records (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Study Flow.

Table 1 presents the demographic and clinical characteristics of the study groups. Overall, group differences were minimal. Patients receiving GC therapy were more likely to be treated with leflunomide (11.1% vs. 3.4%), whereas TNF inhibitor use was more common in the non-GC group (39% vs. 26.7%). Although these differences were statistically significant based on 95% confidence intervals, the standardized differences indicated that the magnitude of imbalance was small. No notable differences were observed between groups in terms of sex, age, BMI, or other treatment regimens.

|

No Glucocorticoid n = 118 |

Glucocorticoid Treated n =90 |

Contrast between groups (95 CI) |

Standardised Difference |

|

|

Female sex, no. (%) |

52 (44.1) |

46 (51.1) |

0.07 (-0.07 to 0.21) |

0.14 |

|

Age |

58.64 (13.11) |

59.10 (14.57) |

0.46 (-3.37 to 4.28) |

0.03 |

|

BMI |

29.24 (6.03) |

28.11 (5.42) |

-1.14 (-2.70 to 0.42) |

-0.2 |

|

Mtx, no. (%) |

56 (47.5) |

38 (42.2) |

-0.05 (-0.19 to 0.08) |

-0.11 |

|

Leflunomide, no. (%) |

4 (3.4) |

10 (11.1) |

0.08 (0.01 to 0.15) |

0.3 |

|

Sulfasalazin, no (%) |

9 (7.6) |

10 (11.1) |

0.03 (-0.05 to 0.12) |

0.12 |

|

TNF inhibitors, no. (%) |

46 (39.0) |

24 (26.7) |

-0.12 (-0.25 to 0.00) |

-0.26 |

|

IL17 inhibitors, no. (%) |

5 (4.2) |

7 (7.8) |

0.04 (-0.03 to 0.10) |

0.15 |

|

Abbreviations: CI: Confidence interval, no: Number; SD: Standard deviation; BMI: Body Mass Index, Mtx: Methotrexate; cDMARD: Conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; TNF: Tumour necrosis factor; IL17: Interleukin 17. All data er presented as Mean (SD) unless other specified. |

||||

Table 1: Patient characteristics across groups.

Incidence of Psoriatic Flares among Patients treated with Glucocorticoids is summarized in Table 2. Within the past year, 47% (56/118) of patients without GC exposure reported a flare, compared with 63.3% (57/90) of those who received GCs (p = 0.0326). This corresponds to an absolute risk difference of 15.9 percentage points (95% CI 2.4–29.3) and a number needed to harm (NNH) of 6.3 (95% CI 3.4–40.9). The unadjusted odds ratio for flare within 1 year was 1.91 (95% CI 1.09–3.35). When flares were assessed within 4 weeks of GC administration (primary endpoint), only 5/90 (6%) GC-treated patients reported a flare; all five cases occurred after intra-articular injection.

|

No GCs n =118 |

GCs Treated n = 90 |

P-value |

|

|

Flair within 4 weeks, no. (%) |

NA |

5 (6) |

NA |

|

Flair within 1 year, no (%) |

56 (47) |

57 (63) |

P = 0.0326 |

|

Abbreviations: no: Number; p.o: GC: Glucocorticoids; NA: Not applicable. *Group difference is calculated from chi-square test. |

|||

Table 2: Correlation between psoriatic flair and corticosteroid intake.

Route of administration analysis (Table 3) showed that intraarticular GC was the only route significantly associated with flares (p = 0.0173). No significant associations were found for oral or intramuscular administration alone or in combination, although subgroup sizes were small.

|

Route of administration |

P-Value |

|

All administration routes combined |

0.0326 |

|

Per oral administration |

0.2316 |

|

Intramuscular administration |

0.8902 |

|

Intraarticular administration |

0.0173 |

|

Per oral and intramuscular administration |

0.0732 |

|

Per oral and intraarticular administration |

1 |

|

Intramuscular and Intraarticular administration |

0.3516 |

|

Statistical testing is performed using chi-square test. |

|

Table 3: Associations between route of administration of GC and psoriasis flare.

Multivariable logistic regression (Table 4) identified GC use as the only independent predictor of flare when adjusting for sex, age, BMI, and PsA treatment (adjusted OR 2.15, 95% CI 1.19–3.95). No other baseline variables were significantly associated with flare risk.

|

Variable |

OR |

95 CI |

|

GC use |

2.15 |

1.19 to 3.95 |

|

Sex |

0.85 |

0.47 to 1.51 |

|

Age |

0.99 |

0.97 to 1.01 |

|

BMI |

1.07 |

1.02 to 1.13 |

|

MTX |

0.78 |

0.39 to 1.57 |

|

Leflunomide |

0.63 |

0.18 to 2.20 |

|

Sulfasalazin |

1.36 |

0.49 to 3.93 |

|

TNF inhibitor |

0.77 |

0.37 to 1.58 |

|

Abbreviations: OR: Odds Ratio, CI: Confidence Interval, GC: Glucocorticoids, BMI: Body Mass Index, MTX: Methotrexate, TNF: Tumour Necrosis Inhibitor. |

||

Table 4: Risk of flair within one year after GC administration adjusted for baseline covariates.

Discussion

This study represents, to our knowledge, the largest real-world cohort analysis specifically examining the association between GC use and psoriasis flares in patients with PsA. We found that GC-treated patients reported a modestly higher 1-year flare rate compared with non-GC patients; however, short-term flares within 4 weeks of GC exposure our primary outcome were uncommon, occurring in only 6% of GC-treated individuals and exclusively following intra-articular injections.

The higher 1-year flare rate among GC-treated patients should be interpreted with caution. Given that GCs are often prescribed during periods of heightened disease activity, this association may largely reflect confounding by indication rather than a direct pharmacological effect. This is consistent with the lack of temporal clustering of flares shortly after most GC administrations and supports the hypothesis that underlying disease activity is a key driver of flare risk. Our finding that intra-articular GC was the only route significantly associated with flares warrants further investigation but should be interpreted conservatively. This association could reflect residual confounding — for example, intra-articular injections may be preferentially used in patients with more active or joint-localised disease, who may also have more unstable skin disease. Subgroup sizes were small, and the association did not persist across other administration routes.

The scarcity of high-quality studies in PsA populations is notable. Our results align with sub analyses from the TICOPA study, in which only a minority of patients showed clinically relevant PASI increases after steroid injections, and with smaller psoriasisfocused studies reporting no clear flare risk from systemic GCs [18]. Historical caution, as reflected in EULAR guidelines, originates largely from older case series such as Ryan & Baker, which involved generalised pustular psoriasis (GPP) and lacked control for spontaneous flare occurrence [9]. These older data, while important in their historical context, provide limited causal inference for plaque psoriasis in PsA.

More recent reviews, including the systematic review by Vincken et al. indicate flare incidences of ≤1.42% across studies, challenging the notion of a substantial GC-associated flare risk [14]. Our findings a low short-term flare rate, but possible signal for intraarticular administration fit within this emerging narrative that the absolute risk is likely low and context-dependent.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of our study include a relatively large, well-characterised PsA cohort, confirmation of diagnosis via CASPAR criteria, and the combination of data with structured patient interviews. Explicit evaluation of a short-term risk window adds temporal resolution missing from many prior studies. However, this study has several inherent limitations due to its retrospective and observational design.

First the study does not account for possible confounding variables, including disease severity and comorbidities, which could independently influence the likelihood of psoriatic flares.

Second, the study encompasses multiple forms of glucocorticoid treatment (oral, intra-articular, intramuscular, among others) without standardized dosage, frequency, or duration of administration. This heterogeneity complicates direct comparisons across different treatment groups and may introduce variability in the observed outcomes.

Thirdly, several biases must be acknowledged, including recall bias and observer bias. Patients were required to recall events from the past year, introducing a potential for underreporting. However, it could be argued that if patients did not recall experiencing a psoriasis flare, such an event’s severity and clinical implications were likely minimal. The reliance on patient-reported outcomes introduces the possibility of misclassification, as the study assumes that patients can accurately and consistently self-report psoriatic flares.

Finally, while our sample size is substantial, it may still be insufficient to detect rare adverse effects of GC therapy, particularly for specific routes of administration.

Implications and future research

Our results suggest that GC-related psoriasis flares are rare in the short term, particularly following oral or intramuscular administration. The possible association with intra-articular GC should be viewed as hypothesis-generating rather than definitive. Future research should prioritise large-scale, prospective designs with: Standardised flare definitions and objective skin assessments, detailed capture of GC dose, duration, and indication; robust control for disease activity and other confounders. And finally, a pre-specified analyses of administration routes and risk windows

Conclusion

In this real-world PsA cohort, short-term psoriasis flares after GC exposure were uncommon and largely limited to patients receiving intra-articular injections. The higher 1-year flare rate among GC users likely reflects underlying disease activity rather than a direct drug effect. These findings, together with emerging literature, question the strength of historical cautions against GC use in PsA but underscore the need for rigorous prospective studies to confirm safety profiles across GC regimens and routes of administration.

References

- Belasco J, Wei N (2019) Psoriatic Arthritis: What is Happening at the Joint? Rheumatol Ther 6(3): 305-315.

- Gossec L, Baraliakos X, Kerschbaumer A, Maarten de Wit, Iain McInnes et al. (2020) EULAR recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis with pharmacological therapies: 2019 update. Ann Rheum Dis 79(6): 700-712.

- Tam LS, Edmund K Li, Lai-Shan Tam (2011) Cardiovascular risk in psoriatic arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 7(9): 542-548.

- Caso F, Chimenti MS, Navarini L, Ruscitti P, Peluso R, et al. (2020) Metabolic Syndrome and psoriatic arthritis: considerations for the clinician. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 16(4): 409-420.

- Lubrano E, Scriffignano S, Perrotta FM (2020) Residual Disease Activity and Associated Factors in Psoriatic Arthritis. J Rheumatol 47(10): 1490-1495.

- Jamnitski A, Symmons D, Peters MJL, Sattar N, McInnes I, et al. (2013) Cardiovascular comorbidities in patients with psoriatic arthritis: a systematic review. Ann Rheum Dis 72(2): 211-216.

- Narayanasamy K, Sanmarkan AD, Rajendran K, Annasamy C, Ramalingam S (2016) Relationship between psoriasis and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Prz Gastroenterol 11(4): 263-269.

- Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, Feldman SR, Gelfand JM, et al. (2009) Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis with systemic nonbiologic therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol 61(3): 451-485.

- Ryan TJ, Baker H (1969) Systemic corticosteroids and folic acid antagonists in the treatment of generalized pustular psoriasis. Evaluation and prognosis based on the study of 104 cases. Br J Dermatol 81(2): 134-145.

- Brody SI (1996) Parenteral triamcinolone in the systemic treatment of psoriasis. Mil Med 131(7): 619-626.

- Coates LC, Helliwell PS (2016) Psoriasis flare with corticosteroid use in psoriatic arthritis. Br J Dermatol 174(1): 219–221.

- Aimo C, Cosentino VL, Sequeira G, Kerzberg E (2019) Use of systemic glucocorticoids in patients with psoriatic arthritis by Argentinian and other Latin-American rheumatologists. Rheumatol Int 39(4): 723-727.

- Gregoire ARF, Britt K DeRuyter, Erik J Stratman (2021) Psoriasis flares following systemic glucocorticoid exposure in patients with a history of psoriasis. JAMA Dermatol 157(2): 198-201.

- Vincken N, Deepak M W Balak, André C Knulst, Paco M J Welsing, Jacob M van Laar (2022) Systemic glucocorticoid use and the occurrence of flares in psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis: a systematic review. Rheumatology (Oxford) 61(11): 4232-4244.

- Eder L, Vinod Chandran, Joanna Ueng, Sita Bhella, Ker-Ai Lee (2010) Predictors of response to intra-articular steroid injection in psoriatic arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 49(7): 1367-1373.

- Haroon M, Ahmad M, Nouman Baig M, Mason O, Riceet J, et al. (2018) Inflammatory back pain in psoriatic arthritis is significantly more responsive to corticosteroids compared to back pain in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Res Ther 20(1): 73.

- Cervini C, G Leardini, A Mathieu, L Punzi, R Scarpa (2005) Psoriatic arthritis: epidemiological and clinical aspects in a cohort of 1,306 Italian patients. Reumatismo 57(3): 139-145.

- Coates LC, Nuria Navarro-Coy, Sarah R Brown, Sarah Brown, Lucy McParland, et al. (2013) The TICOPA protocol (TIght COntrol of Psoriatic Arthritis): a randomized controlled trial to compare intensive management versus standard care in early psoriatic arthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 14:101.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.