GIST, Imatinib, Gastric Pneumatosis: A Case Report

by Marie Yvette R. Amante1, Corazon A Ngelangel1,2*, Jose Celso F. Novenario1, Karl T. Morales1,3, Ray I. Sarmiento1, Lainie FJ Montenegro1

1Asian Hospital and Medical Center, Metro Manila, Philippines

2University of the Philippines-College of Medicine, Manila, Philippines

3University of Santo Tomas-College of Medicine, Manila, Philippines

*Corresponding author: Corazon A Ngelangel, Asian Hospital and Medical Center and University of the Philippines-College of Medicine, Metro Manila, Philippines

Received Date: 05 December 2025

Accepted Date: 11 December 2025

Published Date: 15 December 2025

Citation: Amante MYR, Ngelangel CA, Novenario JCF, Morales KT, Sarmiento RI, et al. (2025). GIST, Imatinib, Gastric Pneumatosis: A Case Report. Ann Case Report. 10: 2478. https://doi.org/10.29011/2574-7754.102478

Abstract

Here is a case of a 74 years old male with chronic co-morbidities and then diagnosed with Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor (GIST) presenting as a lobulated 16.9 x 25 x 17.8 cm mass arising from the fundus and proximal body of the stomach by CT Scan and a bleeding lobulated mass at gastric wall by gastroscopy. After imatinib for 62 days, CT Scan showed gastric pneumatosis occupying the area where the gastric mass is.

Keywords: Gastric pneumatosis; GIST; Imatinib

Introduction

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are considered rare tumors, accounting for less than 1% of all gastrointestinal tumors. Global incidence is estimated at about 10 to 15 cases per million people per year (approximately 1.5 per 100,000 population). Despite their rarity, GISTs are the most common mesenchymal tumors of the gastrointestinal tract, representing around 80% of gastrointestinal non-epithelial tumors and about 5% of all sarcomas. The most frequent primary site for GIST is the stomach (about 63% of cases), followed by the small intestine (around 30%) [1-3].

Imatinib is the first-line treatment for most patients with advanced, unresectable, metastatic, or high-risk gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST). It is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting KIT and PDGFRA mutations, which are common drivers of GIST. In advanced/ metastatic/ unresectable GIST, the standard starting dose is 400 mg orally once daily, continued until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity [4-5].

Imatinib induces partial responses in 65–70% of metastatic GIST cases, and disease stabilization is observed in many others. Median progression-free survival (PFS) is approximately 2–3 years; overall survival is significantly prolonged compared to historical chemotherapy [6].

Imatinib treatment for gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) is generally continued indefinitely in patients with advanced or metastatic disease as long as the therapy is effective and well-tolerated, and the disease remains stable. Clinical trials show that stopping imatinib often leads to rapid disease progression or recurrence, even after 1, 3, or 5 years of disease control. International guidelines recommend that patients with unresectable, metastatic, or recurrent GIST should not stop imatinib unless there is progression or significant toxicity. Disease progression is the main indication to stop imatinib, after which alternative therapies are considered. Evidence shows that continuous, uninterrupted therapy yields better long-term outcomes; imatinib should not be discontinued unless medically necessary [6-11].

A very select subgroup of patients with oligometastatic GIST, who have achieved complete remission via surgery or ablation after long-term imatinib use, may consider stopping imatinib as part of a monitored clinical protocol. In these highly selected cases, about 40% remain progression-free three years after stopping, but most patients will eventually relapse, and imatinib can often regain control if reintroduced. Discontinuation in the adjuvant setting for localized, high-risk GIST follows a fixed course (e.g., 3 years) rather than indefinite therapy [12-13].

Intolerable side effects, comorbidities, or patient preference (with thorough counseling) may also prompt discontinuation, but this carries a high risk of disease flare and should be done with great caution. For patients requiring surgery, imatinib may be temporarily stopped and restarted postoperatively [14-15].

Common side effects include fluid retention, rash, diarrhea, muscle cramps, fatigue, and mild cytopenias. Most adverse effects are manageable, and therapy is typically well tolerated [4].

Gastric pneumatosis can theoretically occur in GIST treated with imatinib, but reports of this specific phenomenon are exceedingly rare.

Case Report

This is a 74 years old male with one after the one development of co-morbidities becoming chronic since 1990 - fatty liver, multinodular goiter, 1st degree AV block, cardiomegaly, aortic valve sclerosis, hypertension, dyslipidemia, non-insulin dependent diabetes, benign prostatic hypertrophy, benign positional paroxysmal vertigo, sleep apnea, diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis, arthritis, non-specific interstitial lung disease/ recurrent pneumonia/ bronchitis, kidney calculus/ cysts, venous insufficiency/ chronic peripheral edema/ incompetent right saphenofemoral venous junction/ chronic venous stasis/ bilateral leg edema, on-off cellulitis, managed by a multidisciplinary clinical specialty team.

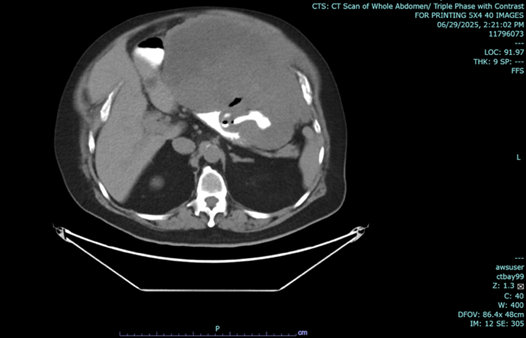

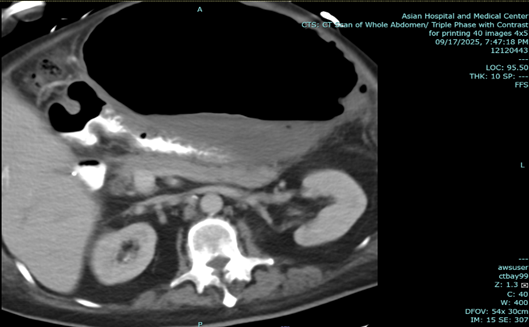

In June 2025, his abdominal CT Scan showed an exophytic lobulated gastric 16.9 x 25 x 17.8 cm mass with central hypodense areas (likely necrosis) arising from fundus and proximal body of stomach, exerting severe mass effect on remaining stomach, pancreas, left hepatic lobes transverse colon, abuts left hemidiaphragm, and distends anterior abdominal wall. Gastroscopy with endoscopic UTS showed a 129.17 x 97.11 mm hypoechoic mass with lobulations at gastric wall adjacent to liver, with some bleeding. Gastric mass biopsy showed GIST, spindle cell type, mitotic rate 4 per 5 mm sq, low grade, CD34+, CD117+, Desmin-, DOG1+, HER-, S100-, Ki67-, 21-30% proliferative index, no loss of nuclear expression of MMR proteins.

Figure 1 a-c: June 29, 2025 Abdominal CT Scan showing hypodense mass.

He started imatinib 7-16 July 2025, at 600 mg a day, stopped when he got admitted for infection (cellulitis) and anemia. He resumed imatinib 400 mg a day 23 July up to 12 September, when he was re-admitted for bilateral pleural effusion noted without malignant cells, acute pulmonary congestion, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in rapid ventricular response, recurrent moderate skin and soft tissue infection of the bilateral lower extremities, considering sepsis, impending acute renal failure, multifactorial anemia and hypoalbuminemia, occult gastrointestinal blood loss, bronchial asthma, metabolic syndrome, for which he was stabilized and then discharged with instructions on out-patient continuing medical management. Imatinib for GIST was resumed after 13 days deferment.

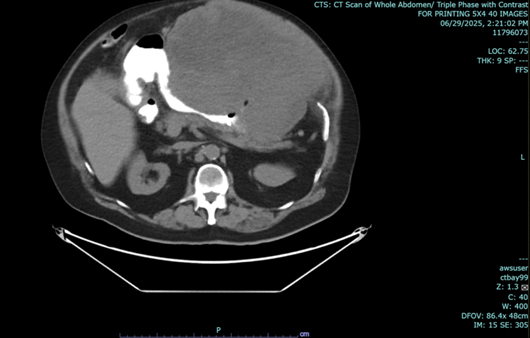

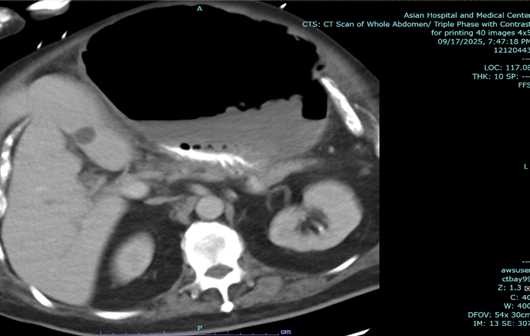

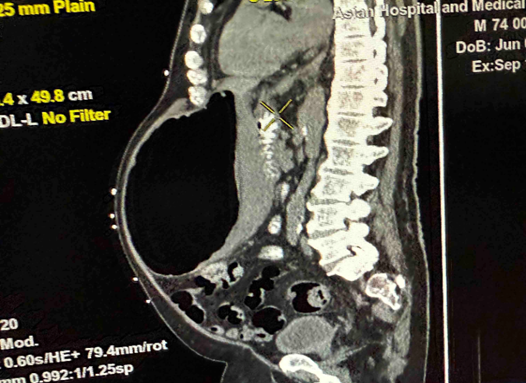

In the above latest admission, his abdominal CT Scan showed gaseous distention of stomach with ill-defined nodular thickening of posterior aspect of the body; the previously noted large lesion in stomach was not clearly demonstrated due to gaseous distended stomach.

Figure 2: a-c: September 17, 2025 Abdominal CT Scan showing previously noted large mass in stomach not clearly demonstrated due to gaseous content.

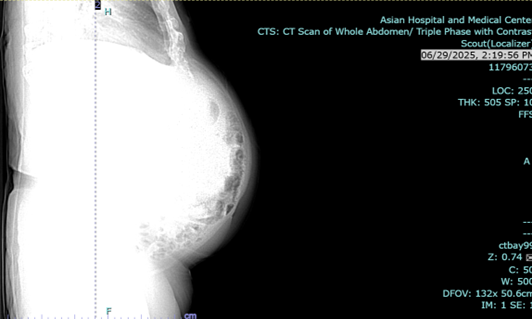

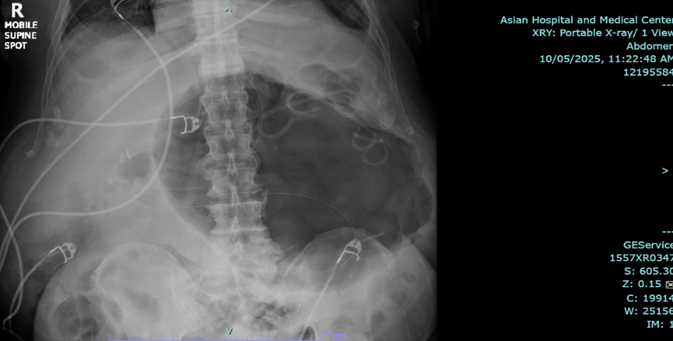

Endoscopic esophagogastroduodenoscopy plus endoscopic internal drainage using plastic stent and insertion of duodenal tube were done on 23 September 2025, repositioned to the jejunum on 29 September 2025. By x-ray (5 October 2025), a gas-filled mass is still appreciated in the upper abdomen, in the region of the stomach. The feeding tube was seen coursing within, with its tip located lateral to the mass, which may be in the distal segment of the stomach. No distinct kink was noted in this study.

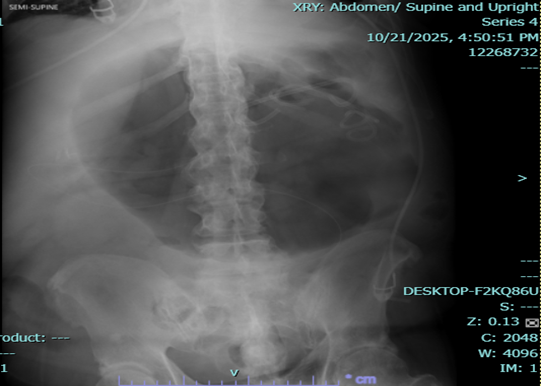

The patient was readmitted for fever and anemia, and resolved accordingly. X-ray of abdomen showed unchanged gas-filled focus.

Figure 3a,b: X-ray of abdomen.

On 13 November 2025, he underwent exploratory laparotomy, sleeve gastrectomy with resection of greater curvature mass and tube jejunostomy; the mass was cystic, 18.5 x 11.0 x 10.0 cm (27% of previous mass size), with tan-brown gelatinous wall, positive for K. pneumoniae and P. aeruginosa. Histopathology indicated stromal tumor, spindle type (residual), histologic grade G1, mitotic rate <5/5 mm2, all margins negative, no lymph nodes found, omentum negative for tumor, moderate risk for progressive disease.

The patient consented for his case report to be written and published together with radiological images; the Asian Hospital and Medical Center IRB approved publication of this case.

Discussion

Pneumatosis intestinalis (PI) encompasses any situation where gas is found in the bowel wall, rather than the lumen. PI occurs in approximately 0.03% of the population. It can affect any age group, although it is more prevalent in older populations than in young adults and infants. In adults, PI is usually benign and found incidentally on imaging. PI itself is not considered a disease, but rather a radiological or pathological sign [16].

Pneumatosis intestinalis can occur in the stomach, though this is considerably rarer than its involvement in the small intestine or colon. When pneumatosis affects the stomach, it is often referred to as gastric pneumatosis or gastric pneumatosis cystoides and presents as gas within the gastric wall [17].

Pneumatosis intestinalis in GIST patients treated with imatinib is very rare, with only scattered case reports (best estimated at < 10; estimated incidence of 1%) and no large series or precise incidence rates available. Systematic reviews of pneumatosis related to targeted therapies primarily identify cases involving sunitinib or bevacizumab rather than imatinib, though a few published reports specifically document imatinib-induced pneumatosis in GIST patients [18-20].

GIST masses treated with imatinib rarely convert directly to "gaseous" content, but rapid tumor necrosis induced by imatinib can lead to unique phenomena such as gas accumulation within the tumor or adjacent tissues, particularly in large or ulcerated GISTs. The most clinically relevant scenarios include tumor necrosis causing bowel wall perforation, development of pneumatosis (gas within the bowel wall), or air trapping from communication with the gastrointestinal lumen due to ulceration or fistula formation [20-22].

In retrospective studies, the stomach has been involved in only about 9% of all cases of gastrointestinal pneumatosis. Most cases in the literature describe either gastric emphysema, which is typically benign and self-limited, or emphysematous gastritis, a much rarer but potentially fatal infectious form [18-19].

Gastric pneumatosis can theoretically occur in GIST treated with imatinib, but reports of this specific phenomenon are exceedingly rare. The medical literature primarily describes pneumatosis intestinalis affecting the small or large intestine during therapy with imatinib, sunitinib, or other targeted agents, but there are no routine or large case series that directly document isolated gastric pneumatosis in GIST patients on imatinib. Most reported cases and reviews address colonic or ileal wall pneumatosis. The mechanism in these cases is believed to involve rapid tumor necrosis, mucosal breakdown, or changes in gastrointestinal wall integrity linked to targeted therapy [22-23].

Gastric pneumatosis specifically remains a rare and poorly documented event. However, it is biologically plausible, especially considering the potential for rapid tumor necrosis, mucosal changes, or local pressure effects as a response to therapy. Gastric pneumatosis is theoretically possible in patients with gastric GIST treated with imatinib. Clinicians should be vigilant for GI wall complications, including the possibility of gastric pneumatosis, especially if patients present with symptoms or imaging findings suggestive of gas within the gastric wall during imatinib treatment [22-23].

Direct conversion of a GIST mass to gaseous content does not occur; rather, gas formation suggests rapid necrosis and risk for serious complications following imatinib therapy, especially in large or ulcerated tumors [21-22,25-26].

Imatinib can cause gas formation in the intestinal or gastric wall through several interconnected mechanisms involving the tumor, mucosa, and gut physiology. Imatinib's anti-tumor efficacy, mucosal effects, motility changes, and immunosuppression act synergistically to create conditions where gas can enter the bowel or stomach wall, manifesting as pneumatosis intestinalis or, more rarely, gastric pneumatosis. The recognized pathways include:

Rapid Tumor Necrosis: Imatinib induces apoptosis and dramatic shrinkage of GIST, which can result in rapid tumor necrosis and breakdown near the mucosal interface. This can compromise the integrity of the gastrointestinal wall, allowing luminal gas to dissect into the submucosa or subserosa. [22, 27-29] Partial ischemic damage or antiangiogenic effects of molecular targeted therapy, including imatinib, can cause gas to accumulate within the bowel wall rather than the solid tumor itself. [21-22] Rapid necrosis from imatinib can destabilize large or ulcerated tumors, leading to perforation or fistula, allowing air from the GI tract to enter and be trapped in the mass or tumor cavity. Communication between the mass cavity and the GI lumen via ulcer or fistula acts as a "check valve," allowing air entrapment [26].

Altered Mucosal Integrity: Tyrosine kinase inhibition by imatinib may reduce mucosal repair, contributing to local microinjuries or ulceration that increase permeability for intraluminal gas and bacteria [27,29].

Immunosuppression: Imatinib may exert non-neutropenic immunosuppressive effects, potentially increasing susceptibility to infection or impairing healing of minor injuries in the gut wall, further permitting gas infiltration. [27, 29].

Decreased Intestinal Motility: Imatinib may impair motility, leading to increased intraluminal pressure and gas production. Sluggish transit allows prolonged exposure of mucosa to gas-forming bacteria, which can facilitate gas dissection into the bowel wall [27].

Bacterial Overgrowth or Translocation: Mucosal barrier dysfunction and immunosuppression may permit gas-producing bacteria to infiltrate the bowel wall, directly producing intramural gas (as in some cases of emphysematous gastritis) [22, 29].

In summary, the pathogenesis of imatinib-related pneumatosis combines the effects of rapid tumor response, impaired mucosal healing, altered GI motility, and changes in mucosal defense—all creating conditions for gas to permeate the stomach or intestinal wall.

Clinical implications are inferred [21,26]: Large GISTs (≥10 cm), especially those with ulceration, are at risk and require close monitoring at imatinib initiation due to potential for rapid necrosis, fever, and subsequent perforation. Gas formation generally signals a serious complication (e.g., perforation, necrosis, pneumatosis) rather than a therapeutic endpoint, and urgent intervention may be required. Conservative management of drug-induced pneumatosis/ perforation is possible in selected cases, but surgical intervention may be necessary if fistula or uncontrolled perforation is present. CT and other imaging modalities can detect cystic-necrotic changes, gas pockets, and pneumatosis as signs of response or complication after imatinib therapy. Gas in the tumor region does not signify benign transformation, rather it is a marker of potential acute pathology.

For GIST patients who develop pneumatosis intestinalis or gastric pneumatosis, best first line management practices emphasize initial conservative treatment, close clinical monitoring, and targeted intervention if complications develop. [21,30-31].

These would entail: a) Discontinuation on imatinib (or the implicated molecular targeted therapy) to halt further mucosal or vascular compromise [21, 30-31]; b) Bowel rest, intravenous fluids, and parenteral nutrition are crucial supportive measures; c) Broad-spectrum antibiotics are recommended to prevent or treat associated bacterial infection [30-31];d) Oxygen therapy (including hyperbaric techniques, may be beneficial for persistent or symptomatic cases without acute surgical indications) [30-32]; e) Regular abdominal examination and repeat imaging (CT, X-ray) are used to monitor resolution or progression of pneumatosis [30-31].

Overall, Conservative management is successful in most pneumatosis cases associated with imatinib, unless additional complications arise. Drug rechallenge may be considered if pneumatosis resolves and no contraindicating complications remain, but requires multidisciplinary assessment. Surgical intervention is generally avoided unless an acute abdomen or progressive findings are present. Emergency surgery is reserved for patients with signs of peritonitis, bowel perforation, sepsis, or unresolving intestinal ischemia. Drainage or other interventions may be indicated if abscesses or fistulas form. Decisions should be made by a multidisciplinary team, including oncologists, surgeons, and radiologists [21,30-31].

Management of GIST tumors with gas accumulation centers on prompt recognition of potentially serious complications, such as perforation or pneumatosis, and tailoring interventions based on clinical severity and underlying pathology. [21,33] Gas accumulation within or around a GIST can reflect necrosis, perforation, fistula formation, or pneumatosis intestinalis, most commonly following rapid tumor response to therapy (e.g., imatinib). [33-34].

Acute presentations, such as abdominal pain, fever, peritonitis, or signs of sepsis, require rapid clinical assessment, laboratory evaluation, and urgent cross-sectional imaging. Recognized perforation or uncontrolled infection mandates immediate surgical intervention often with exploratory laparotomy and resection of the affected bowel segment or mass to prevent widespread peritonitis or sepsis. For GISTs complicated by localized perforation or abscess, surgical options may include segmental bowel resection, repair, and (in extensive cases) colostomy creation. Extensive metastatic or unresectable disease presents technical challenges but still warrants surgery when life-threatening complications (e.g., diffuse gas, peritonitis) occur. Postoperative management may require intensive care, mechanical ventilation, support for organ failure, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and nutritional interventions. Multidisciplinary collaboration (oncology, surgery, radiology, pathology, critical care) is crucial for optimal outcomes [33,35].

In cases of mild or asymptomatic gas accumulation (e.g., limited pneumatosis intestinalis without peritonitis), conservative management (observation, bowel rest, parenteral nutrition, antibiotics) may be considered in selected patients [21, 23]

For unresectable/metastatic GIST, targeted therapy with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) like imatinib, sunitinib, or regorafenib remains the mainstay. Dose escalation and genotyping should be considered after initial therapy failure. Close follow-up with repeat imaging and laboratory monitoring is essential to detect further complications or disease progression [33,36-37].

In summary, best practices favor conservative management for GIST-associated pneumatosis with escalation to surgery only for severe complications, supported by multidisciplinary collaboration and vigilant clinical and imaging follow-up.

Pneumatosis itself is not an independent predictor of poor long-term outcome in GIST patients on imatinib, but complications, interruptions in therapy, and severe presentations (e.g., portal venous gas, sepsis) can negatively affect survival and disease control.

Pneumatosis in GIST patients, particularly those on imatinib, does not inherently indicate a poor long-term prognosis if managed appropriately, but it can significantly disrupt or complicate treatment and requires careful multidisciplinary management [21].

Most GIST patients who develop pneumatosis due to imatinib or other TKIs recover fully with conservative management (drug cessation, supportive measures), especially if there are no signs of bowel perforation or sepsis. In most reported cases, molecular targeted therapy (including imatinib) could be restarted once findings resolved, though some required dose adjustment or ongoing monitoring to prevent recurrence. Patients who require surgery due to complications (perforation, abscess, fistula) can experience delays, interruptions, or discontinuations in systemic GIST therapy potentially impacting overall tumor control and survival, particularly in advanced or metastatic disease.

Evidence suggests that the majority of GIST patients with TKI-induced pneumatosis do not have increased mortality directly from the pneumatosis itself; severe complications (peritonitis, sepsis) are the main predictors of poor outcomes. The presence of portal venous gas, in contrast to isolated bowel wall pneumatosis, may signal a particularly poor prognosis. There is no data to suggest that pneumatosis, when resolved without surgical morbidity or mortality, worsens long-term GIST-specific survival compared to patients without the complication, as long as systemic therapy is resumed.

In GIST treated with imatinib, the appearance of gastric pneumatosis can be a radiological marker of tumor response (e.g., due to necrosis or mucosal changes) but also serves as a warning sign for possible complications like perforation or infection.

If gastric pneumatosis is a result of rapid tumor necrosis, therapy effect (such as imatinib-induced changes), or mechanical factors, and is not complicated by infection, perforation, or ischemia, the prognosis can be favorable and managed conservatively, with many cases resolving without surgical intervention.

This case had infection in the cystic component of the mass, noted upon surgical removal, and treated accordingly. Histopathology showed 73% partial response to imatinib, but 18.5 cm widest diameter residual tumor, with intermediate risk for progressive disease needing adjuvant imatinib.

Declarations

Ethical Approval and Consent to participate

A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

With the patient’s consent, ethical approval was given.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Availability of supporting data

The patient’s medical record is available at the hospital for review.

Competing interests

There is no competing interest on behalf of the authors in reporting this case.

Funding

There is no institutional fund provided for this case report.

Authors' information and contributions

All authors are doctors of Asian Hospital and Medical Center and members of the multidisciplinary team who took care of the patient and contributed to the case report writing and review.

Acknowledgements

We thank our patient for consenting to present her clinical history to the scientific audience at large.

References

- Rare Disease Advisor. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor epidemiology [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Jul 20]. Available In Online.

- Khan J, Ullah A, Waheed A, Karki NR, Adhikari N, et al. (2022). Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST): a population-based study using the SEER database, including management and recent advances in targeted therapy. Cancers (Basel). 14: 3689.

- Medscape. GISTs [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Jul 20]. Available in Online.

- Lopes LF, Bacchi CE. (2010). Imatinib treatment for gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST). J Cell Mol Med. 14: 42-50.

- Serrano C, Martín-Broto J, Asencio-Pascual JM, López-Guerrero JA, Rubió-Casadevall J, et al. (2023). 2023 GEIS guidelines for gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 15: 17588359231192388.

- Balachandran VP, DeMatteo RP. (2014). Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: who should get imatinib and for how long? Adv Surg. 48: 165-183.

- Heinrich MC. (2010). Imatinib treatment of metastatic GIST: don’t stop (believing). Lancet Oncol. 11: 910-911.

- Denu RA, Somaiah N. (2024). Imatinib in advanced GIST: if it’s working, don’t stop a good thing. Lancet Oncol. 25: 1105-1107.

- Reid T. (2013). Reintroduction of imatinib in GIST. J Gastrointest Cancer. 44: 385–92.

- National Cancer Institute. Stopping Gleevec: what happens if GIST patients discontinue imatinib? [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Oct 6]. Available in Online.

- Yip D, Zalcberg J, Blay JY. (2025). Imatinib alternating with regorafenib compared to imatinib alone for the first-line treatment of advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumor: the AGITG ALT-GIST intergroup randomized phase II trial. Br J Cancer. 132: 897-904.

- Hompland I, Boye K, Wiedswang AM, Papakonstantinou A, Røsok B, et al. (2024). Discontinuation of imatinib in patients with oligometastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumour who are in complete radiological remission: a prospective multicentre phase II study. Acta Oncol. 63: 288-93.

- Hompland I, Boye K, Papakonstantinou A, Røsok B, Joensuu H. (2022). Discontinuation of imatinib in patients with oligo-metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor who are in complete radiological remission: a prospective multicenter phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 40: 11535.

- Life Raft Group. Stopping Gleevec [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Oct 6]. Available in Online.

- van de Wal D, Roets E, Bleckman RF, Nützinger J, Heeres BC, et al. (2024). Treatment dilemmas in patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) who experienced imatinib-induced pneumonitis: a case series. Curr Probl Cancer Case Rep. 13: 100280.

- Tahiri M, Levy J, Alzaid S, Anderson D. (2015). An approach to pneumatosis intestinalis: factors affecting your management. Int J Surg Case Rep. 6: 133-7.

- Pastor-Sifuentes FU, Moctezuma-Velázquez P, Aguilar-Frasco J. (2020). Neumatosis gástrica: espectro de la enfermedad. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 85: 219-20.

- Shaik MR, Ranabhat C, Shaik NA, Duddu A, Bilgrami Z. (2023). Gastric pneumatosis in the setting of diabetic ketoacidosis. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2023: 6655536.

- Tagliaferri A, Melki G, Mohamed A, Cavanagh Y, Grossman M. (2023). Gastric pneumatosis in immunocompromised patients: a report of 2 cases and comprehensive literature review. Radiol Case Rep. 18: 1152–5.

- Grabill N, Louis M, Cawthon M, Conway J, Chambers J. (2024). Managing locally advanced GIST complicated by perforation: a case report and comprehensive review. Radiol Case Rep. 19: 4824–31.

- Shinagare AB, Howard SA, Krajewski KM, Zukotynski KA, Jagannathan JP, et al. (2012). Pneumatosis intestinalis and bowel perforation associated with molecular targeted therapy: an emerging problem and the role of radiologists in its management. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 199: 1259–65.

- Gazzaniga G, Villa F, Tosi F, Pizzutilo EG, Colla S, et al. (2022). Pneumatosis intestinalis induced by anticancer treatment: a systematic review. Cancers (Basel). 14: 1666.

- Asahi Y, Suzuki T, Sawada A, Kina M, Takada J, et al. (2018). Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis secondary to sunitinib treatment for gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 12: 432-8.

- Viswanathan C, Bhosale P, Ganeshan DM, Truong MT, Silverman P. (2012). Imaging of complications of oncological therapy in the gastrointestinal system. Cancer Imaging. 12: 163–72.

- Chen MY, Bechtold RE, Savage PD. (2002). Cystic changes in hepatic metastases from gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) treated with Gleevec (imatinib mesylate). AJR Am J Roentgenol. 179: 1059–62.

- Kong SH, Yang HK. (2013). Surgical treatment of gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Gastric Cancer. 13: 3-18.

- Vijayakanthan N, Dhamanaskar K, Stewart L, Connolly J, Leber B, et al. (2021). A review of pneumatosis intestinalis in the setting of systemic cancer treatments, including tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Can Assoc Radiol J. 63: 312-317.

- Hecker A, Hecker B, Bassaly B, Hirschburger M, Schwandner T, et al. (2010). Dramatic regression and bleeding of a duodenal GIST during preoperative imatinib therapy: case report and review. World J Surg Oncol. 8: 47.

- Chang CJ, Shen CI, Wu CL, Chiu CH. (2022). Pneumatosis intestinalis induced by targeted therapy. Postgrad Med J. 98: 10.

- Calabrese E, Ceponis PJ, Derrick BJ, Moon RE. (2017). Successful treatment of pneumatosis intestinalis with associated pneumoperitoneum and ileus with hyperbaric oxygen therapy. BMJ Case Rep. 2017: bcr2016218990.

- Zhao X, Wang J, Li P, Wang M, Wang N. (2025). Conservative management of pneumatosis intestinalis with spontaneous pneumoperitoneum: a compelling case report. J Clin Images Med Case Rep. 6: 3408.

- Tahiri M, Levy J, Alzaid S, Anderson D. (2015). An approach to pneumatosis intestinalis: factors affecting your management. Int J Surg Case Rep. 6: 133–7.

- Grabill N, Louis M, Cawthon M, Conway J, Chambers J. (2024). Managing locally advanced GIST complicated by perforation: a case report and comprehensive review. Radiol Case Rep. 19: 4824–31.

- Medscape. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) overview [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Oct 6]. Available in Online.

- Kubincova M, Mertens K, De Cuyper K, Mortier L, Verheyen L. (2022). Acute perforation of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Eurorad [Internet].

- Koo DH, Ryu MH, Kim KM, Yang HK, Sawaki A,, et al. (2016). Asian consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Cancer Res Treat. 48: 1155–66.

- British Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology. GIST management guidelines [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2025 Oct 6]. Available in Online.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.