Giant Renal Angiomyolipoma: A Case Series and Review of the Literature

by Expósito Ibáñez E1*, Domínguez Esteban M1,3, Campos Juanatey F1,3,4, Calapaqui Terán AK2, Sánchez Gil M1, García Herrero J1, Azcárraga Aranegui G1, Latatu Córdoba MA1, Arnáiz Jiménez F1, Crespo Bañón J1, Fernández López B1, Gutiérrez Baños JL1,3,4

1Urology Department, Marqués de Valdecilla University Hospital, Santander, Cantabria, Spain.

2Pathological Anatomy Department, Marqués de Valdecilla University Hospital, Santander, Cantabria, Spain.

3Urology Department, Marqués de Valdecilla Research Instiute (IDIVAL), Santander, Cantabria, Spain.

4Faculty of Medicine, University of Cantabria, Santander, Cantabria, España.

*Corresponding author: Ibáñez EE, Urology Department, Marqués de Valdecilla University Hospital, Santander, Cantabria, Spain.

Received Date: 02 November, 2024

Accepted Date: 07 November, 2024

Published Date: 09 November, 2024

Citation: Expósito Ibáñez E, Domínguez Esteban M, Campos Juanatey F, Calapaqui Terán AK, Gutiérrez Baños JL, et al. (2024) Giant Renal Angiomyolipoma: A Case Series and Review of the Literature. J Oncol Res Ther 9: 10254. https://doi.org/10.29011/2574-710X.10254.

Abstract

Giant Renal Angiomyolipomas (AML) are benign kidney tumors exceeding 10cm in size. AMLs are usually sporadic and asymptomatic. The lack of prospective trials and a limited number of large retrospective case series in this field has made it challenging for urologists to determine the optimal treatment strategy. Our aim is to demonstrate different treatment options, illustrated by several cases managed at our centre.

Keywords:

Giant Renal Angiomyolipoma; Asymptomatic; Active Treatment; Case Series

Abbreviations

AML: Angiomyolipoma.

CT: Computed Tomography.

Introduction

Renal angiomyolipoma (AML) is a benign kidney condition composed of dysmorphic blood vessels, smooth muscle and fatty tissue [1]. AML is the most common benign renal tumor in clinical practice, with a general prevalence of 0.44%. Sporadic AMLs are typically diagnosed between the ages of 50 and 60, and are more frequent in women. These tumors usually present as a unilateral mass and have a slow growth rate. About 20% of cases have an association with tuberous sclerosis complex, where AMLs appears earlier, grow rapidly and are often bilateral and multifocal. Tuberous sclerosis is commonly caused by mutations in either TSC1 (which encodes hamartin) or TSC2 genes (which encodes tuberin). These proteins are involved in the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway and their mutations result in various clinical manifestations including epilepsy, neurocognitive issues, autism, astrocytomas, cardiac rhabdomyomas, retinal hamartomas, hypomelanotic macules and facial/ungual angiofibromas [2]. AMLs are often diagnosed incidentally. Although often asymptomatic, up to 15% of patients may present with Wunderlich syndrome, of which AML is the primary cause. ‘Giant renal AMLs’ refers to tumors larger than 10cm, although they are relatively rare [3]. The lack of clinical trials difficult the selection of optimal treatment strategies. Because of the significant bleeding risk associated with the size of these tumors, active management is essential. Kidneysparing treatments are preferred given their benign nature [4]. We describe three cases of giant renal AML successfully managed in our centre.

Case Presentation

Between January 2023 and May 2024, 3 patients, aged 50 (patient A), 75 (patient B), and 76 (patient C), were diagnosed with giant renal AML. No relevant previous diseases or associated genetic syndromes were identified. During our initial evaluation, patients reported vague symptoms, such as abdominal pain, urinary incontinence, general syndrome... In cases with larger tumor sizes, physical examination revealed a palpable abdominal mass. Laboratory tests did not show any abnormal results. The lesions were first identified incidentally through an abdominal ultrasound. To further characterize the tumors, a contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan was performed, which confirmed a mass compatible with AML, with sizes ranging from 13 to 24 cm. Given the known association between these tumors and tuberous sclerosis, all patients were referred to Oncology department. An exhaustive physical examination, a full blood test, and an eye examination were performed, none of them showed any abnormalities. Additionally, a transthoracic echocardiogram and a brain MRI were carried out. A genetic study was also conducted which ruled out mutations in TSC1 and TSC2 genes. Following diagnosis, active treatment strategies were chosen and implemented for each case.

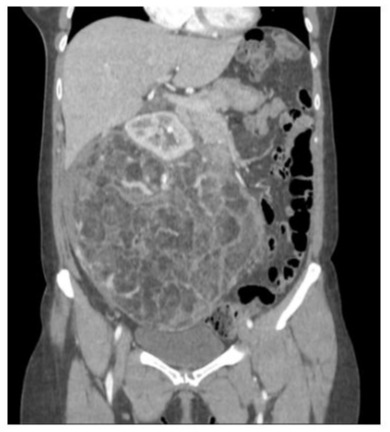

Patient A arrived at the Emergency department after experiencing two episodes of presyncope, which were accompanied by severe abdominal pain. A physical examination revealed a palpable abdominal tumor. The abdominal x-ray showed a large mass that had displaced the bowel (figure 1). Additionally, a CT scan showed findings compatible with Wunderlich syndrome, but there was no evidence of active bleeding (figure 2).

Figure 1: The abdominal x-ray reveals the displacement of the bowel loops into the left hemiabdomen.

Figure 2: CT scan of patient A shows an AML with a maximum diameter of 24,5cm.

Patient B was admitted to Internal Medicine ward for further investigation of a general syndrome and fever that had persisted for one month. A comprehensive study, including a body CT, revealed a voluminous left retroperitoneal mass up to 20 cm, suggestive of a renal AML, with large-caliber vessels inside and partial thrombosis of some of the more anterior veins.

Patient C was referred from Primary Care to Urology Department for urinary incontinence. Imaging studies revealed a 13.5cm angiomyolipoma.

Results

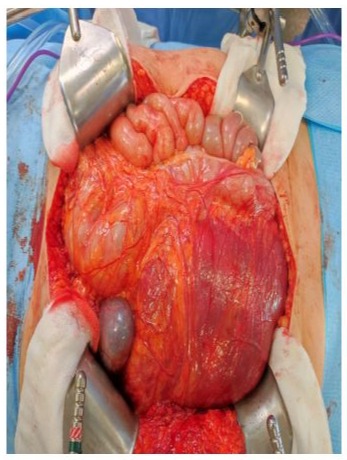

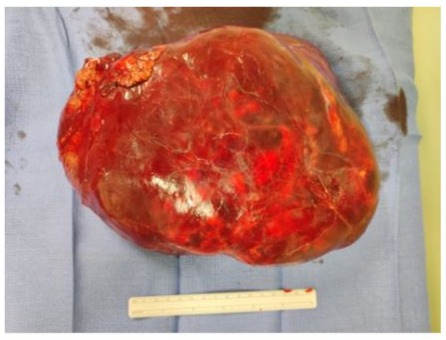

Due to the size of the lesion and the high risk of bleeding, an open partial nephrectomy was performed on patient A. A midline laparotomy exposed a large mass, which was excised under arterial clamping, with a total ischemia time of eight minutes (figure 3). The surgical specimen weighed 2480 grams (figure 4). The surgical procedure lasted 3 hours and two units of red blood cells were transfused afterwards. Peritoneal drainage was removed on 8th day, and patient was discharged.

Figure 3: Midline laparotomy.

Figure 4: Surgical Specimen.

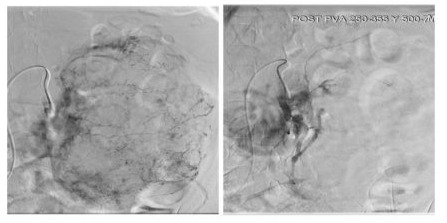

In patient B, the risk of surgical resection was found to be higher due to patient’s age and comorbidities. To reduce bleeding risk, selective embolization of tumor branches was successfully carried out (figure 5), with no adverse effects observed. Four months later, the lesion had decreased in size, so we performed an open partial nephrectomy due to the patient’s favorable general condition.

Figure 5: Before and after selective renal embolization.

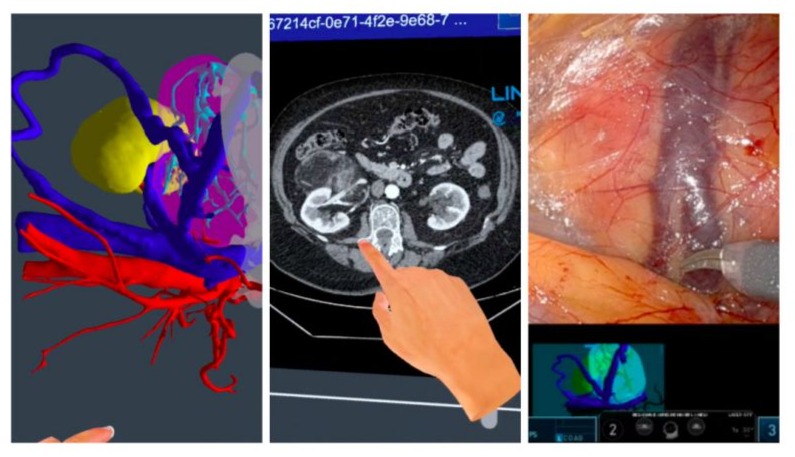

The lesion on patient C patient was of a slightly smaller size, so we decided to underwent a robotic partial nephrectomy. The procedure was facilitated by a three-dimensional model, which was developed

beforehand using imaging tests. This model allowed optimal identification and control of the lesion’s neovascularization (figure 6). The surgery was completed without complications and the patient was discharged on the third postoperative day.

Figure 6: Correlation between preoperative 3D reconstruction and CT scan with intraoperative findings.

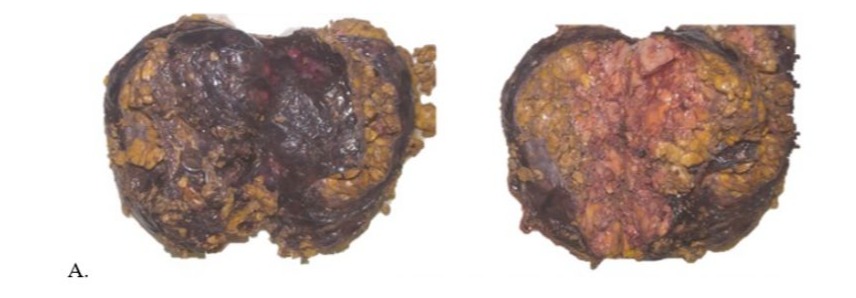

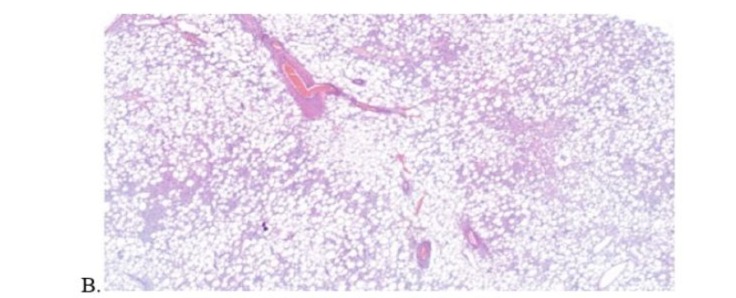

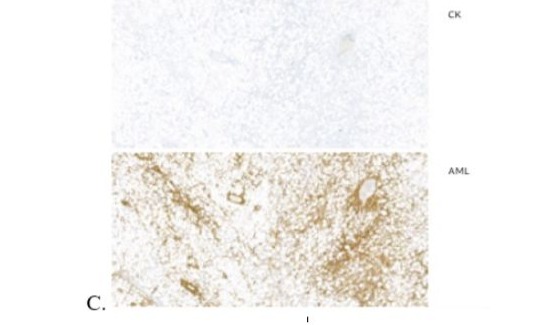

In all cases, both the immediate and late postoperative periods were uneventful. Microscopic and immunohistochemical analysis of the pathological anatomy confirmed the presence of AML (figure 7). Serial sections showed a proliferation of adipose tissue, smooth muscle and blood vessels. The tissued stained positive for actin and negative for cytokeratin.

Figure 7: Main pathological anatomy findings. (A. Macroscopic study, B. Microscopic study, C. Immunohistochemical studies -actin and cytokeratin-)

Discussion

Most AMLs are asymptomatic and are often discovered incidentally through non-invasive imaging techniques. Some patients may exhibit symptoms resulting from active bleeding. In most cases, ultrasound can provide an initial diagnosis, but a CT scan is necessary to confirm it. The definitive diagnosis relies on the identification of fat within the tumor, and a renal biopsy is not needed for confirmation.

For large AMLs, active treatment should be considered due to the significant risk of bleeding. The choice to pursue active treatment can be influenced by patient factors such as age and comorbidities. This report outlines three different strategies for achieving kidneysparing treatment, despite the considerable size of these lesions. We demonstrated that renal embolization is a less invasive method for the initial treatment phase, with the objective of allowing surgical intervention at a later time. The main disadvantages of this selective arterial embolization approach include a higher rate of recurrence and the potential need for further treatment [4].

Surgery is not the preferred first-line treatment for AML associated with tuberous sclerosis because of its bilateral and multifocal characteristics. Consequently, we perform a genetic study in all cases. The use of drugs such as Everolimus, an inhibitor of the mTOR pathway, has been investigated. Several clinical trials have demonstrated that patients with tuberous sclerosis treated with Everolimus experienced a reduction in AML size. However, it remains unclear whether Everolimus could prove an effective treatment for sporadic AML, as the number of studies conducted is too limited to provide a conclusive answer [5].

Conclusion

AML is a frequent renal tumor although it rarely reaches sizes larger than 10 cm. When it exceed this size, it presents a significant challenge in daily urological practice. This case series, based on current scientific evidence, aims to demonstrate effective management strategies for such cases. Further research is necessary to determine whether patients might benefit from from medical treatment before or after surgery.

References

- Tsai HY, Lee KH, Ng KF, Kao YT, Chuang CK (2019) Clinicopathologic analysis of renal epithelioid angiomyolipoma: Consecutively excised 23 cases. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 35: 33.

- Parin AW, Dmochowski RR, Kavoussi LR, Peters CA, Wein A (2020) Campbell Walsh Wein Urology: 12th Edition. Elselvier 96: 2121-2132. e5.

- Ljungberg B, Albiges L, Bedke J, Bex A, Capitanio U, et al. (2023) EAU guidelines on renal cell carcinoma. Edn presented at the EAU Annual Congress Milan ISBN 978-94-92671-19-6.

- Fernández-Pello S, Hora M, Kuusk T, Tahbaz R, Dabestani S, et al. (2020) Management of Sporadic Renal Angiomyolipomas: A Systematic Review of Available Evidence to Guide Recommendations from the European Association of Urology Renal Cell Carcinoma Guidelines Panel. Eur Urol Oncol 3: 57.

- Bissler JJ, Kingswood JC, Radzikowska E, Zonnenberg BA, Frost M, et al. (2016) Everolimus for renal angiomyolipoma in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex or sporadic lymphangioleiomyomatosis: extension of a randomized controlled trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant 31: 111.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.