Four and Five-Level Anterior Cervical Corpectomy and Fusion for Infectious Cervical Deformity: A Case Series

by George Crabill*, Kaleb Derouen, Jacob Chaisson, Ellery Hayden, Wesley Shoap, Gabriel Tender

Department of Neurosurgery, Louisiana State University Health Science Center, New Orleans, LA, USA

*Corresponding Author: George A. Crabill, Department of Neurosurgery, Louisiana State University Health Science Center, New Orleans, LA, USA

Received Date: 10 October 2025

Accepted Date: 15 October 2025

Published Date: 17 October 2025

Citation: Crabill G, Derouen K, Chaisson J, Hayden E, Shoap W, et al. (2025). Four and Five-Level Anterior Cervical Corpectomy and Fusion for Infectious Cervical Deformity: A Case Series. 10: 2430. https://doi.org/10.29011/2574-7754.102430

Abstract

Anterior cervical corpectomy and fusion (ACCF) provides an effective means of relieving spinal cord compression while restoring cervical alignment and stability. When infection leads to osseous destruction and cervical deformity, multilevel ACCF may be required to restore alignment and prevent neurologic decline. However, outcomes of four and five-level ACCF for extensive infection and cervical alignment remain poorly described. We present a series of three patients who underwent four or five-level ACCF for severe deformity secondary to methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus osteomyelitis. All patients had recent anterior reconstruction with subsequent hardware failure and progressive kyphosis. Each underwent staged or circumferential reconstruction. Despite radiographic correction and technical success, two patients died from overwhelming sepsis, and one left the hospital against medical advice following early neurologic improvement. Although surgical goals of decompression and deformity correction were achieved, the overall morbidity and mortality remained high. Outcomes were largely affected by infection burden and systemic comorbidities rather than surgical factors alone.

Keywords: Anterior cervical corpectomy and fusion; Cervical osteomyelitis; Cervical kyphosis; Multi-level cervical fusion

Introduction

Anterior cervical corpectomy and fusion (ACCF) is a wellestablished surgical technique utilized by neurosurgeons and orthopaedic surgeons alike to decompress the spinal cord and nerve roots while also restoring alignment and stability. Indications for ACCF include degenerative disease, trauma, tumor, and infection, with cervical spondylitic myelopathy being the most common [1-3]. Despite its utility, ACCF carries substantial risks. The rate of implant failure and cage subsidence is reported as high as 13.3% and 42.5%, respectfully [4,5]. The risk of complications is further heightened when treating medically fragile patients with pyogenic cervical osteomyelitis, in whom infection leads to osseus destruction and weakening of surrounding supportive structures [6]. These changes can result in profound cervical deformity, spinal cord compression, and neurologic deterioration [7]. To date, there is a paucity of literature examining four and five-level ACCFs performed for infectious cervical deformity. In this case series, the authors outline the clinical course and outcomes of three patients that underwent multilevel ACCF for severe cervical osteomyelitisrelated deformity.

Case Presentations

Patient #1

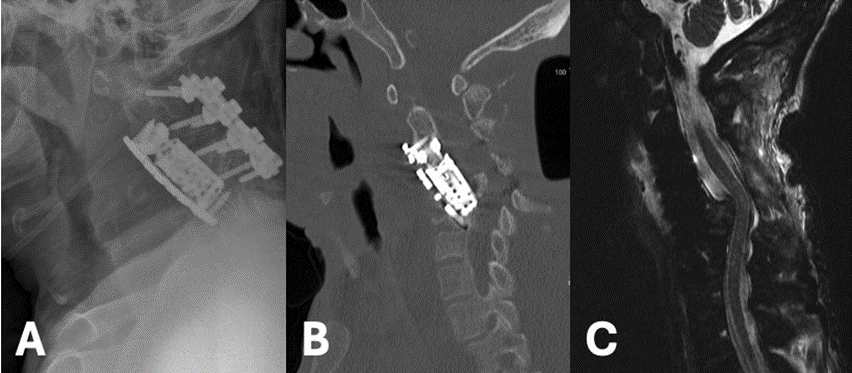

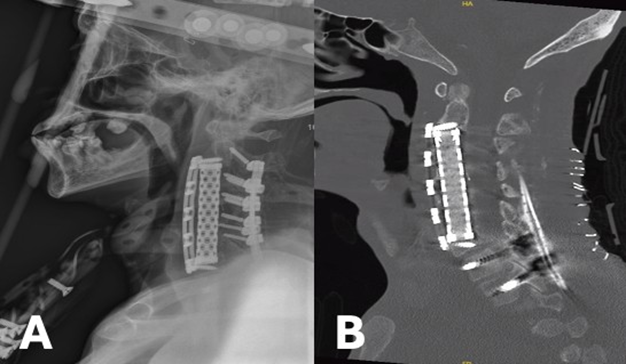

52-year-old male with past medical history significant for diabetes mellitus (DM), end-stage renal disease (ESRD), heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), deep venous thrombus (DVT) with inferior vena cava (IVC) filter presented to the hospital with a chief complaint of bilateral upper extremity (BUE) deltoid weakness with associated paresthesias and bowel incontinence for six days. Past surgical history significant for revision C3-C5 ACCF and C2-C5 posterior cervical fixation one month prior for methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) osteomyelitis. Cervical x-ray (XR) and computed tomography (CT) Cervical Spine discovered subsidence of the corpectomy hardware and cervical kyphosis resulting in retropulsion of the bone and hardware (Figure 1A and B). MRI Cervical Spine confirmed severe canal stenosis and draping of the spinal cord over the retropulsed fragment (Figure 1C). The patient was placed in cervical traction using Gardner-Wells tongs, which improved the cervical kyphosis and the patient’s neurologic exam. On hospital day (HD) one, the patient was taken to the operating room for revision corpectomy to include C3-C6 and extension of the posterior cervical construct. Post-operatively, the patient regained full strength and sensation. CT scan completed on post-operative day (POD) three demonstrated early subsidence and thus the patient was placed in a halo brace (Figure 2). Unfortunately, patient’s hospital course was complicated by worsening gastrointestinal bleeding and ultimately septic shock. He passed away one month following surgery.

Figure 1: Lateral XR (A) and Sagittal CT Cervical Spine without Contrast (B) Demonstrating severe subsidence of the cervical cage with retropulsion, C5 fracture, and the resulting severe kyphotic deformity. Sagittal T2 MRI Cervical Spine without Contrast shows severe cervical canal stenosis and draping of the cervical cord over the retropulsed fragment (C).

Figure 2: Post-operative lateral XR showing improved cervical alignment and the halo brace (A). Post-operative sagittal CT Cervical Spine without Contrast demonstrating proper position of anterior and posterior hardware (B).

Patient #2

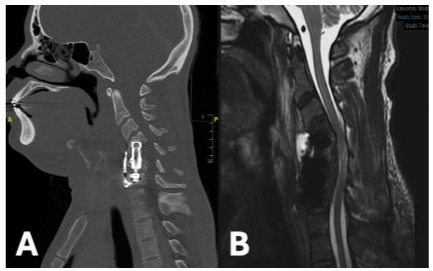

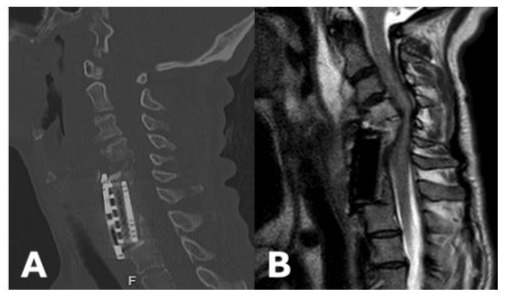

42-year-old man with past medical history significant for intravenous drug use (IVDU), untreated Hepatitis C (HCV), endocarditis and retropharyngeal abscess returned to the hospital with a chief complaint of right upper extremity (RUE) weakness and dysphagia. Past surgical history includes C5-C6 ACCF one month prior for MRSA osteomyelitis and associated spinal epidural abscess, after which the patient left against medical advice (AMA) before posterior fixation could be performed. CT Cervical Spine discovered cervical kyphosis and cage subsidence (Figure 3A). MRI Cervical Spine confirmed severe canal stenosis as well as a prevertebral abscess (Figure 3B). The patient was placed in cervical traction using Gardner-Wells tongs, which improved the cervical deformity. His RUE weakness, consisting of 3/5 deltoid and 4/5 bicep strength, was persistent despite improvement in alignment. On HD3, an anterior corpectomy revision was planned, however, only a washout was performed due to extensive infection burden and frank purulence. The patient was then positioned prone and a posterior cervicothoracic fusion from C3-T2 was completed. On HD14, once medically cleared, the patient returned to the operating room and a C3-C6 ACCF using an expandable titanium cage (Figure 4). Two-weeks following surgery the patient regained full strength throughout except 4/5 strength in right deltoid. Unfortunately, the patient again left AMA.

Figure 3: Sagittal CT Cervical Spine without Contrast (A) and T2 MRI Cervical Spine without Contrast (B) demonstrating subsidence of anterior hardware and cervical kyphosis causing severe canal stenosis and cord compression.

Figure 4: Post-operative sagittal CT Cervical Spine without Contrast showing improved alignment and anterior hardware (A). Sagittal T2 MRI Cervical Spine without Contrast confirming patent canal with relief of cord compression (B).

Patient #3

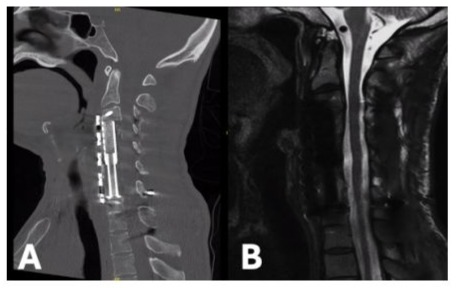

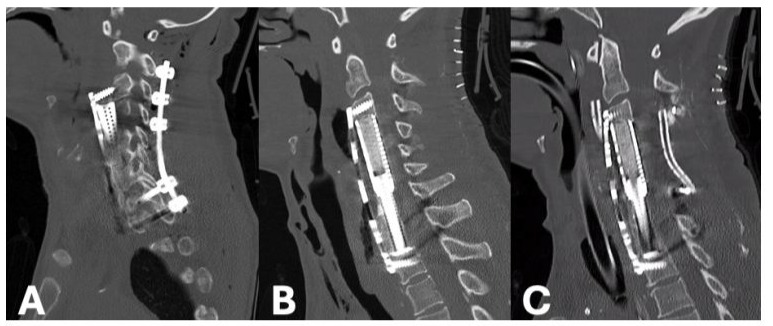

43-year-old female with past medical history significant for IVDU, chronic HCV, endocarditis, and depression returned to the hospital with a chief complaint of BLE paralysis and BUE paresis for two days. Past surgical history includes C6-C7 ACCF three months prior for MRSA osteomyelitis. Exam findings significant for 0/5 motor strength throughout BLEs and 2/5 throughout BUEs. CT Cervical Spine found fracture of the C5 vertebral body with hardware subsidence (Figure 5A). MRI Cervical Spine demonstrated significant canal stenosis with cord compression and large prevertebral abscess (Figure 5B). The patient was placed in cervical traction using Gardner-Wells tongs while in the emergency department. There was moderate improvement in cervical kyphosis, however no improvement in neurologic function. She was then taken to the operating room for revision ACCF extending from C4-T1 using an expandable titanium cage and C2-T2 posterior fixation. Post-operative CT Cervical Spine discovered significant displacement of the anterior hardware and dislodgement of cranial screws (Figure 6A). She returned to the operating room emergently for correction of hardware, with focus on maximizing purchase through increased screw length and diameter (Figure 6B). Postoperatively, the patient’s neurologic exam improved to antigravity throughout. Two days later, she experienced recurrence of BLE paralysis. MRI Cervical Spine discovered diffuse spinal cord swelling throughout the cervical region. She was taken emergently to the operating room for posterior cervical decompression which was completed without complications (Figure 6C). She returned to the intensive care unit intubated. Unfortunately, she soon thereafter developed septic shock from an intra-abdominal source and passed away two weeks later.

Figure 5: Sagittal CT Cervical Spine without Contrast demonstrating osseus destruction and focal cervical kyphosis above the corpectomy hardware (A). Sagittal T2 MRI Cervical Spine without Contrast showing significant cord compression (B).

Figure 6: Post-operative sagittal CT Cervical Spine without Contrast showing significant displacement of the anterior corpectomy cage and plate (A). Repeat CT completed after emergent revision of anterior hardware (B). CT Cervical Spine following posterior cervical decompression (C).

Discussion

ACCF remains a valuable surgical technique for decompression of neural elements and restoration of cervical alignment. While one and two-level ACCF have been well established, each additional level comes with increased complexity and risk of complications. The complexity and risk is further compounded when addressing infectious pathology, which can compromise bone quality and soft tissue structures [6]. Properly dealing with the infection and concomitant deformity poses a significant challenge. The case series presented here demonstrates that four and fivelevel ACCF performed for infectious cervical deformity represents a highly complex and morbid undertaking. Each of our patients presented after prior anterior reconstruction that had failed due to recurrent/persistent MRSA osteomyelitis, hardware subsidence, and progressive kyphotic collapse. Despite meticulous surgical planning and technical success in achieving decompression and alignment, two of three patients ultimately succumbed to overwhelming sepsis. These cases here underscore that four or five-level ACCF in the setting of active or recently treated infection carries grave risk and should only be pursued when neurologic compromise or mechanical instability necessitate surgical intervention. Surgeons should proceed with caution, recognizing the high likelihood of medical and surgical complications.

Several peri-operative considerations may aid with reducing complications and optimizing outcomes. Pre-operatively, cervical traction can play an pivotal role in beginning to restore cervical alignment [8,9]. Additionally, traction can allow for ligamentotaxis of retropulsed fragments if the posterior longitudinal ligament is intact. Intra-operatively, creating the most biomechanically sound construct is of paramount importance. This can be achieved by maximizing screw purchase through longer, bicortical fixation, when able [10,11]. Circumferential fixation has been proven to be of superior strength, especially when bone quality is poor [12,13]. Posterior fixation should be completed as soon as feasible. Postoperatively, the patient should be kept in an external orthosis. Rigid cervical collars are likely the most universally available however, a halo vest may be warranted in some instances.

Comprehensive, multidisciplinary management is essential when caring for medically fragile patients who require extensive surgical intervention. Collaboration among surgical, medical, and rehabilitative teams offer the best opportunity to optimize both short-term and long-term outcomes.

Conclusion

In summary, four and five-level ACCF represent high risk procedures that should be reserved for patients with instability and/or neurologic compromise. These cases demand detailed preoperative planning, intraoperative execution, and vigilant post-operative care. Even with optimal management, substantial morbidity and mortality remains.

Declarations

Contributors: All authors contributed to planning, literature review and conduct of the review article. All authors have reviewed and agreed on the final manuscript.

Competing interests: None

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable

Ethics approval and consent to participate: Not applicable

Availability of data and materials: Not applicable

Funding: No Funding

References

- Özgen S, Naderi S, Özek MM, Pamir MN. (2004). A retrospective review of cervical corpectomy: indications, complications and outcome. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 146: 1099-1105.

- Foreman M, Foster D, Gillam W, Ciesla C, Lamprecht C. (2024). Management Considerations for Cervical Corpectomy: Updated Indications and Future Directions. Life. 14: 651.

- Hartmann S, Tschugg A, Obernauer J, Neururer S, Petr O. (2016). Cervical corpectomies: results of a survey and review of the literature on diagnosis, indications, and surgical technique. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 158: 1859-1867.

- Ji C, Yu S, Yan N. (2020). Risk factors for subsidence of titanium mesh cage following single-level anterior cervical corpectomy and fusion. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 21: 32.

- Hartmann S, Kavakebi P, Wipplinger C. (2018). Retrospective analysis of cervical corpectomies: implant-related complications of one- and two-level corpectomies in 45 patients. Neurosurg Rev. 41: 285-290.

- Franklin D, Fisher WAM, Blumberg JM, Guiroy A, Galgano M. (2024). Technical Nuances of Anterior Column Construction for the Treatment of Osteomyelitis-Induced Cervical Kyphoscoliotic Deformity: An Operative Video Illustration. World Neurosurg. 183: 70.

- Mehkri Y, Felisma P, Panther E, Lucke-Wold B. (2022). Osteomyelitis of the spine: treatments and future directions. Infectious Diseases Research. 3: 3.

- Shen X, Wu H, Shi C. (2019). Preoperative and Intraoperative Skull Traction Combined with Anterior-Only Cervical Operation in the Treatment of Severe Cervical Kyphosis (>50 Degrees). World Neurosurg. 130: e915-e925.

- Saleh H, Yohe N, Razi A, Saleh A. (2018). Efficacy and complications of the use of Gardner-Wells Tongs: a systematic review. Journal of Spine Surgery. 4: 123.

- Hitchon PW, Brenton MD, Coppes JK, From AM, Torner JC. (2003). Factors affecting the pullout strength of self-drilling and self-tapping anterior cervical screws. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 28: 9-13.

- Dhar UK, Menzer EL, Lin M. (2023). Factors influencing cage subsidence in anterior cervical corpectomy and discectomy: a systematic review. Eur Spine J. 32: 957-968.

- Türkmen T, Kale A, Uslan Y, Demir T. (2025). Evaluating fixation techniques to prevent subsidence in cervical corpectomy models using low and high-density polyurethane blocks. Proc Inst Mech Eng H. PP: 239.

- Hartmann S, Thomé C, Keiler A, Fritsch H, Hegewald AA. (2015). Biomechanical testing of circumferential instrumentation after cervical multilevel corpectomy. Eur Spine J. 24: 2788-2798.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.