Focus Group Ratings and Discussions of Alaryngeal Communication Modalities: Preliminary Data on Employable Voice Attributes

by Stephanie M Knollhoff*

Department of Speech, Language and Hearing Sciences, University of Missouri-Columbia, Columbia, MO, United States

*Corresponding author: Stephanie Knollhoff, Department of Speech, Language and Hearing Sciences, University of MissouriColumbia, 701 S. 5th Street, 308 Lewis Hall, Columbia, MO 65211, United States

Received Date: 09 November, 2024

Accepted Date: 05 December, 2024

Published Date: 10 December, 2024

Citation: Knollhoff SM (2024) Focus Group Ratings and Discussions of Alaryngeal Communication Modalities: Preliminary Data on Employable Voice Attributes. Curr Trends Otolaryngol Rhinol 6: 136. https://doi.org/10.29011/2689-7385.000036

Abstract

Purpose: The purpose of this study was to investigate listener impressions of alaryngeal communication modalities, more specifically employable voice attributes. Expanding upon previous research that noted individuals to be likable and intelligent but not employable, this study was designed to capture information regarding modality, context, and characteristics. Methods: Forty-five individuals listened to 24 audio samples. Participants were provided a visual analog scale and instructed to rate their agreement on three statements. Additionally, participants were provided with an open text box to type any further thoughts regarding the stimuli. Lastly, focus groups were facilitated during which participants could openly share their thoughts. Results: Results demonstrated a significant difference between the communication modalities, with electrolarynx (EL) having the highest overall mean rating followed by tracheoesophageal speech (TES) and esophageal speech (ES). Spontaneous speech was rated significantly higher than the grandfather passage. A significant difference was observed between the three rating statements. Five thematic categories were developed to characterize the open-text responses and focus group discussion with nearly half of all open-text responses categorized as speech and voice attributes. Conclusion: Results from this study indicate EL rated more favourably than ES or TES, an agreement with results from previous studies using listeners outside of speech-language pathology. However, mean ratings for each modality did not extend much beyond the halfway mark, indicating the work that still needs to be done in understanding what makes a voice ‘employable.’

Keywords: Alaryngeal communication; Listener impressions; Esophageal speech; Electrolarynx; Tracheoesophageal speech; Quality of life

Introduction

Total laryngectomy, a surgical procedure involving the removal of the larynx and rerouting of the trachea, is primarily used for individuals with laryngeal cancer. Laryngeal cancer is one of the most common cancers of the upper aerodigestive tract and accounts for over 12,000 new cases per year in the United States [1]. One does wonder however, if the recent global health pandemic which caused a strain on the medical profession, including lack of access to services and increased time for procedures to take place, will result in an increase in total laryngectomy procedures [2]. Nonetheless, there are three primary options for verbal communication in the United States after receiving a total laryngectomy: electrolarynx (EL), esophageal speech (ES), and tracheoesophageal speech (TES). Each communication modality has a unique way of creating a vibratory mechanism and ultimately allowing for verbal communication. Research on impressions of alaryngeal communication modalities dates back over fifty years. Earlier research focused on speech intelligibility and respiration, while more recent research appears to target listener impressions and perceptions [3-6]. Results from previous research on alaryngeal communication modalities commonly conclude TES as the most preferred, ES in the middle, and EL as least preferred [6-8]. Noteworthy is that several previous investigations utilized individuals currently in, or training to enter, the communication disorders field as listeners. Knollhoff and colleagues (2021) investigated listener impressions using individuals from the lay public. Results from that study navigated away from the more common preference hierarchy noting ES to be the most preferred female speaker stimuli and TES the most preferred male speaker stimuli. It is imperative that speech-language pathologists working with this population understand each communication modality in addition to their implications on overall quality of life.

Quality of Life

Total laryngectomy intervention has psychological, physical, and social consequences with decreased quality of life after receiving the surgery commonly reported [9-10]. Specifically, individuals who undergo the procedure note employment, social, and physical difficulties as well as mental health disorders [1113]. Furthermore, previous research reported more than half of respondents who received a total laryngectomy reporting at least a ‘somewhat stressful event’ related to the procedure. In the same study, 42% of respondents noted “limitations in physical ability, appearance, or lifestyle due to cancer” as the most stressful aspect of receiving a total laryngectomy [9]. Changes in appearance and/ or disfigurement, like those associated with treatment for head and neck cancer, can be socially stigmatizing and may impair an individual’s ability to conduct activities of daily living [14-16]. Consequently, this population is at an increased risk for mental health disorders [15].

The incident rate of mental health disorders in the head and neck cancer population is on the rise. In a previous research study there was nearly a 10% increase in mental health disorders after receipt of a head and neck cancer diagnosis [15]. Of specific interest to the laryngeal cancer population is the fact that patients with a history of tobacco and/or alcohol use were at significantly higher odds of receiving a mental health disorder diagnosis. Furthermore, receiving multi-modal cancer treatment increased odds of being diagnosed with a mental health disorder when compared to the single cancer treatment modality group [15].

Cancers of the head and neck and their comorbidities are some of the most expensive to treat [17]. Head and neck cancers have been linked to individuals from lower socioeconomic statuses, resulting in greater financial hardship for these patients [18-19]. Consequently, head and neck cancer survivors who experience financial hardships often delay, discontinue, or forgo medical care [20]. Adding to the financial burden is the loss of employment within this population. These serious economic and occupational issues result in reduced quality of life [18-19].

Employment

Approximately one-third to half of the individuals diagnosed with head and neck cancer become functionally disabled after treatment and are unable to return to work [19,21]. We still cannot discount, however, the significant number of individuals who would like to return to the workforce either out of desire or necessity. Mode of communication has been directly linked to quality of life [9]. Voice differences or the absence of verbal communication has been noted as a significant limiting factor to interactions, both socially and occupationally [5,22].

There have been few previously reported studies investigating employment status and its relationship with head and neck cancer. It has been stated that over 50% of individuals with head and neck cancer were unable to return to work upon completion of cancer treatment despite the fact they were working prior to receiving the diagnosis [21,23]. One previous study reported that individuals with laryngeal cancer were the least likely head and neck cancer subgroup to return to work post cancer treatment. Of the individuals with laryngeal cancer that did return to work, over 30% were required to change or modify their occupational duties. Results further indicated that individuals with more advanced stage tumors, as is the case for most individuals who receive a total laryngectomy, either did not return to work or were required to modify their occupational duties [24]. Employment status has been directly linked to quality of life in individuals with head and neck cancer. Unemployed individuals display a significantly lower quality of life [23,25]. Furthermore, the unfavorable economic status that can accompany being unemployed in this population also negatively affects quality of life [23].

Head and neck cancer poses a substantial economic burden. Cancer is currently the leading cause of medical-related bankruptcy, and bankruptcy is a mortality risk factor in individuals with cancer [26-27]. Lu and colleagues (2019) published findings stating 51% of participants reported cancer-related financial stress, 53% of participants reported cancer-related financial strain, and 45% of participants reported both stress and strain. Results further indicated that participants noting both financial stress and strain demonstrated the worst scores on head and neck specific questionnaires in the emotional, functional, and physical domains. These results also supported previous findings that individuals with head and neck cancer are more susceptible to financial hardships post cancer diagnosis due in part to out of pocket expenses to receive care, products, and rehabilitation, high rates of unemployment, and lower socioeconomic status [18,28-30].

Statement of Purpose

The goal of this research line is to enhance understanding of employable voice attributes in individuals who utilize a verbal alaryngeal communication modality. A previous investigation conducted by this author concluded that lay-public listeners of alaryngeal communication modes noted individuals to be likable and intelligent but not employable [5]. Therefore, this study was designed to gain more knowledge on listener impressions of alaryngeal communication modalities specifically as it pertains to employability. Three specific research questions were targeted, 1. Are listener impressions altered based on communication modality? 2. Does the context of employment (i.e., first choice versus simply hiring) affect listener impression ratings? and 3.

How do vocal attributes influence ratings of employability?

Method

Participants

This study was approved by the institutional review board at the author’s home institution. Recruitment took place through flyers, social media posts, email, and word of mouth. All participants received a $10 gift card upon completion.

A total of 45 individuals consented to participate. Participants were required to meet the inclusion criteria of 18-80 years of age (M = 20.20 years, SD = 1.79), currently enrolled in coursework at the author’s home institution, access to technology that allowed for electronic participation, and adequate hearing to listen and rate audio samples. Due to the ongoing health pandemic at the time of data collection, all participation was completed over the virtual meeting platform Zoom. Prior to participation, individuals submitted a screening questionnaire. In addition to screening for inclusion criteria, data was also obtained on the participant’s reported area of study. Participants were placed into data collection groups in which there were no more than two participants from the same area of study. This was an intentional design of the current study as previous research has documented listener impressions of speech-language pathology students. The current study had a specific goal to obtain a sample size that included areas of study other than those seeking to support individuals with communication impairments. This design approach stives to obtain the impressions of individuals potentially in positions to make decisions regarding employment such as business majors. Further information regarding the participants is in Table 1.

|

Variable |

Count (%) |

|

Sex |

|

|

Female |

36 (80%) |

|

Male |

9 (20%) |

|

Level of Study |

|

|

Undergraduate |

41 (91.1%) |

|

Graduate |

4 (8.9%) |

|

Education Program |

|

|

Accountancy |

1 (2.2%) |

|

Agriculture |

1 (2.2%) |

|

Biology |

2 (4.4%) |

|

Business Administration |

7 (15.6%) |

|

Clinical & Diagnostic Sciences |

1 (2.2%) |

|

Communication |

3 (6.7%) |

|

Digital Storytelling |

1 (2.2%) |

|

Engineering |

3 (6.7%) |

|

Health Sciences |

4 (8.9%) |

|

Journalism |

7 (15.6%) |

|

Nursing |

1 (2.2%) |

|

Political Science |

1 (2.2%) |

|

Public Health |

1 (2.2%) |

|

Speech, Language, Hearing Science |

7 (15.6%) |

|

Undeclared |

1 (2.2%) |

|

Geological Sciences (graduate) |

1 (2.2%) |

|

Mechanical & Aerospace Engineering (graduate) |

1 (2.2%) |

|

Public Health (graduate) |

1 (2.2%) |

|

Speech-Language Pathology (graduate) |

1 (2.2%) |

|

Ethnicity |

|

|

American Indian or Alaska Native |

1 (2.2%) |

|

Asian |

3 (6.7%) |

|

Black or African American |

4 (8.9%) |

|

White or Caucasian |

37 (82.2%) |

Table 1: Participant demographics.

Stimuli

Stimuli included audio samples of individuals who utilize EL, ES, or TES as their primary mode of communication. Researchers made attempts to age match speakers of the speech stimuli (range: 41-75 years, M = 60.5); both sexes were equally represented. In addition to a total laryngectomy, 33% of participants received bilateral neck dissection and 17% of participants received a unilateral neck dissection. Each speech stimuli speaker completed the sentence portion of the Speech Intelligibility Test with a score of 85% or greater. Three research assistants orthographically transcribed each sentence with the final intelligibility score being the average of the three raters. Additionally, speech stimuli speakers had been using their mode of alaryngeal communication for at least twoand-a-half years. Stimuli included a portion of the grandfather passage (You wish to know all about my grandfather. Well, he is nearly 93 years old, yet he still thinks as swiftly as ever. He dresses himself in an old black frock coat, usually several buttons missing. A long beard clings to his chin giving those who observe him a pronounced feeling of the utmost respect) and spontaneous speech (Tell me a little bit about yourself), both approximately 30 seconds. Each data collection group rated eight speech samples of a single alaryngeal communication modality, two male and two females for both the grandfather passage and spontaneous speech for each rating statement.Audio samples were analyzed for pitch, intensity, and noise-toharmonic ratio. Overall, the pitch range across stimuli speakers spanned from 85.34-410.61Hz. There was no difference noted in pitch between the two stimuli tasks (Grandfather passage M = 173.59, SD = 106.37; spontaneous speech M = 186.19, SD = 92.58) or speaker sex (male M = 169.27, SD = 94.80; female M = 190.51, SD = 103.63). A statistically significant difference (p = .004) was noted between communication modalities (ES M = 183.79, SD = 31.44; EL M = 102.96, SD = 30.36; TES M = 252.92, SD = 128.84). Overall, the intensity range across stimuli speakers spanned from 41.45-73.41. There was no difference noted in intensity between the two stimuli tasks (Grandfather passage M = 65.12, SD = 3.93; spontaneous speech M = 63.87, SD = 8.65), between communication modalities (ES M = 61.43, SD = 3.29; EL M = 66.37, SD = 3.72; TES M = 65.67, SD = 10.11), or speaker sex (male M = 65.78, SD = 4.89; female M = 63.20, SD = 7.97). Overall, the noise-to-harmonic ratio across stimuli speakers spanned from .14-.74. There was no difference noted in noise-toharmonic ratio between the two stimuli tasks (Grandfather passage M = .40, SD = .19; spontaneous speech M = .41, SD = .19) or speaker sex (male M = .42, SD = .16; female M = .39, SD = .21). A statistically significant difference (p < .001) was noted between communication modalities (ES M = .42, SD = .11; EL M = .21, SD = .05; TES M = .59, SD = .13).

Procedures

Participants joined a secure virtual meeting room and were guided through the study by research personnel. No information was provided pertaining to the speech stimuli, stimuli speakers, or communication modalities. Participants were instructed to listen to the audio sample and rate their level of agreement to the provided statement. Three statements were provided for each stimulus: I would hire this person for employment, this person would be my first choice to hire after an interview, I would take on this person for a job. Participants provided ratings using a 100mm visual analog scale that was anchored on both ends; ‘strongly disagree’ being all the way on the left end and ‘strongly agree’ the anchor on the right end. The larger the number, the more agreement with the statement. Participants were also provided an open text box to enter any additional comments. Stimuli was presented one at a time, with one rating at a time, resulting in each group listening to a total of 24 audio samples. The presentation format for one data collection group is provided in Table 2. Participants were instructed they would only be able to listen to the stimuli once. Audio samples and statements were randomized across groups to eliminate any potential order effects. Additionally, participants were given no more than 30 seconds to provide their response in an attempt to obtain initial reactions.

|

Audio Sample |

Tracheoesophageal Stimuli |

Rating Statement |

|

1 |

Female 1, spontaneous speech |

This person would be my first choice to hire after an interview |

|

2 |

Female 2, spontaneous speech |

This person would be my first choice to hire after an interview |

|

3 |

Male 1, spontaneous speech |

I would take on this person for a job |

|

4 |

Female 2, spontaneous speech |

I would take on this person for a job |

|

5 |

Female 2, grandfather passage |

This person would be my first choice to hire after an interview |

|

6 |

Male 2, spontaneous speech |

I would take on this person for a job |

|

7 |

Male 1, grandfather passage |

I would hire this person for employment |

|

8 |

Male 1, grandfather passage |

This person would be my first choice to hire after an interview |

|

9 |

Female 1, spontaneous speech |

I would take on this person for a job |

|

10 |

Female 1, spontaneous speech |

I would hire this person for employment |

|

11 |

Male 2, grandfather passage |

This person would be my first choice to hire after an interview |

|

12 |

Male 2, grandfather passage |

I would hire this person for employment |

|

13 |

Male 1, spontaneous speech |

This person would be my first choice to hire after an interview |

|

14 |

Female 2, grandfather passage |

I would take on this person for a job |

|

15 |

Male 2, grandfather passage |

I would take on this person for a job |

|

16 |

Female 1, grandfather passage |

I would hire this person for employment |

|

17 |

Male 1, grandfather passage |

I would take on this person for a job |

|

18 |

Female 1, grandfather passage |

This person would be my first choice to hire after an interview |

|

19 |

Female 2, grandfather passage |

I would hire this person for employment |

|

20 |

Male 1, spontaneous speech |

I would hire this person for employment |

|

21 |

Female 1, grandfather passage |

I would take on this person for a job |

|

22 |

Male 2, spontaneous speech |

I would hire this person for employment |

|

23 |

Male 2, spontaneous speech |

This person would be my first choice to hire after an interview |

|

24 |

Female 2, spontaneous speech |

I would hire this person for employment |

Table 2: Example of stimuli presentation during data collection.

Next, participants were transitioned into the focus group discussion portion of the study. Participants were instructed to unmute their microphones and engage in open discussion. To guide and facilitate the discussion each group was provided with four prompts: Tell us why you provided the ratings you did, Please tell us about the quality or attributes of the voices you heard, We would be interested in hearing more about your ratings as you progressed through the samples, and Tell us anything else you would like to share. Research personnel asked follow-up and clarifying questions as needed to support data collection, but otherwise did not actively participate in the conversation after providing the prompt. Total participation time was approximately 60 minutes.

Data Analysis

Listening rating data were extracted, cleaned, and compiled for analysis. Visual analog responses were analyzed by calculating responses to the nearest hundredth millimetre, frequencies, and means. Open text response and focus group data were transcribed and analyzed qualitatively using a general thematic analysis process. Braun and Clarke’s methods were used to support this analysis [31-32]. Research personnel reviewed the text responses several times prior to collectively discussing their impressions. Based on those discussions, five initial categories were developed to which research personnel then coded the responses. A comparison of coding was conducted with any inconsistencies being noted. A consensus agreement was used to resolve and recode inconsistencies. Exemplary responses for each theme were identified, and the frequency and the proportion of responses for each theme were tabulated.

Results

Visual Analog Scale Ratings

Overall, results demonstrated a statistically significant difference between communication modalities (ES M = 41.51, SD = 24.01; EL M = 53.15, SD = 30.56; TES M = 47.19, SD = 26.07; p < .001). Further analysis revealed significant differences between ES and EL (p < .001), ES and TES (p = .015), and EL and TES (p = .008). When considering only context of speech stimuli, results collapsed across communication modalities revealed a significant difference (p = .006) between the grandfather passage (M = 45.13, SD = 26.72) and spontaneous speech (M = 49.69, SD = 27.98). There was no difference noted between speaker sex (female M = 47.20, SD = 27.51; male M = 47.63, SD = 27.40). However, a statistically significant difference (p <.001) was determined to exist between the three employability rating statements, I would hire this person for employment (M = 49.23, SD = 27.23), This person would be my first choice to hire after an interview (M = 42.49, SD = 26.88), I would take on this person for a job (M = 50.53, SD = 27.60). Further analysis revealed significant differences between This person would be my first choice to hire after an interview and both remaining statements, I would hire this person for employment (p = .003), and I would take on this person for a job (p < .001). Results from each of the rating statements will be further explored below. Table 3 provides details on the visual analog scale rating outcomes.

Table 3: Visual analog scale rating outcomes. |

I would hire this person for employment

When considering only the ratings that were made for the statement I would hire this person for employment, there was a difference (p = .04) noted between communication modalities: ES (M = 44.86, SD = 23.63), EL (M = 53.76, SD = 31.46), TES (M = 48.81, SD = 25.38). Post-hoc analysis revealed a significant difference (p = .038) between ES and EL. Investigation of stimuli context revealed no statistical difference between the grandfather passage (M = 47.19, SD = 26.70) and spontaneous speech (M = 51.25, SD = 27.67).

This person would be my first choice to hire after an interview

A statistically significant difference was noted between communication modalities on the ratings of this statement (p < .001; ES M = 33.77, SD = 21.10, EL M = 51.39, SD = 30.15, TES M = 41.79, SD = 25.67). Further analysis revealed differences between EL and both other groups, ES (p < .001) and TES (p = .01). Investigation of stimuli context revealed no statistical difference between the grandfather passage (M = 39.97, SD = 25.64) and spontaneous speech (M = 45.02, SD = 27.91).

I would take on this person for a job

There was no difference noted between communication modalities when investigating ratings from this statement: ES (M = 45.95, SD = 25.40), EL (M = 54.29, SD = 30.24), TES (M = 50.99, SD = 26.46). Investigation of stimuli context also revealed no statistical difference between the grandfather passage (M = 48.26, SD = 27.18) and spontaneous speech (M = 52.82, SD = 27.91).

Open Text Response Results

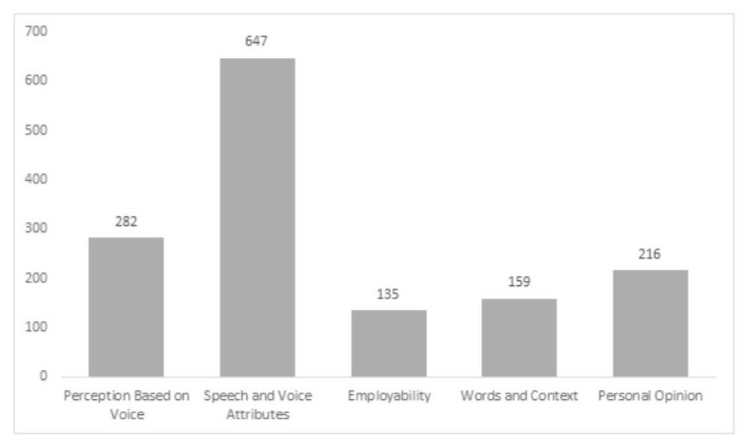

Five themes were developed based on participant typed responses in the provided text boxes: perception based on voice, speech and voice attributes, employability, words and context, and personal opinion. Each theme was noted across all alaryngeal communication modalities. The most common theme was speech and voice attributes (45%) with the least common theme being employability (9.4%). Figure 1 provides information on the total number of responses for each theme.

Figure 1: Number of open text responses categorized to each theme.

Theme 1: Perception Based on Voice

Approximately 20% of all open text box responses revealed that participant impressions were about the speaker (i.e., age, health status). Theme one was approximately one-quarter of the total ES and TES open text comments, 28.6%, and 25.1% respectively. However, only 5.4% of EL open text comments were categorized in this theme. The following are direct responses related to theme one:

“Seems like the[re] may be health issues like maybe being an ex-smoker. Seems older and sick therefore maybe not as able to complete many jobs.”

“She sounds barely alive. Gasping for the next breath. I would be ready with 9-1-1 on my phone screen every time she was around if I hired her.”

Theme 2: Speech and Voice Attributes

Theme two was the most frequently occurring and accounted for roughly half of the total ES and EL comments, 53.2% and 47.8% respectively, and approximately 36% of the total TES comments. Examples of responses regarding rate of speech, vocal quality, and speech intelligibility included:

“Hard to understand due to it being higher pitched and the static, could interfere with his/her occupation.”

“Sounds like a robot which is not truly desirable for an employee, but she is loud enough to be heard and is understood when she speaks which is good.”

Theme 3: Employability

Less than 10% of all comments were direct statements regarding employability. TES had the highest number of comments (13.5%) linked to theme three when compared to the other two modalities, with EL (10.4%) closely behind, and ES having the fewest number of comments (3%) directly linked to employability. Some examples of responses categorized into theme three include:

“Wouldn’t be my first choice but if she was my only choice I wouldn’t min[d].”

“Maybe not the most professional voice but possible but if he fit the job I would hire him.”

Theme 4: Words and Context

Approximately 11% of all open text box responses were related to the specific words and message within the stimuli. Theme four accounted for 14% of EL comments, 12% of TES comments, and 6.6% of ES comments. The following are direct responses related to theme four:

“The words he is saying sounds like he is accomplished.”

“The way her voice box was affected but was grateful that it was saved, shows her perspective on life which would be valuable in the workplace.”

Theme 5: Personal Opinion

Theme five was comprised of the participants’ personal opinions. EL had the highest number of comments (22.3%) linked to theme five when compared to the other two modalities, with TES (13.5%) closely behind, and ES having the fewest number of comments (8.7%). Most open text comments categorized to theme five, which totalled 15% of the overall comments, were participants noting that they either simply did or did not like the voice. Specific examples include:

“Unpleasant to listen to. It makes me cringe and he sounds unhealthy.”

“Very kind and loving, devoted to her family and specifically her grandson.”

Focus Group Discussions

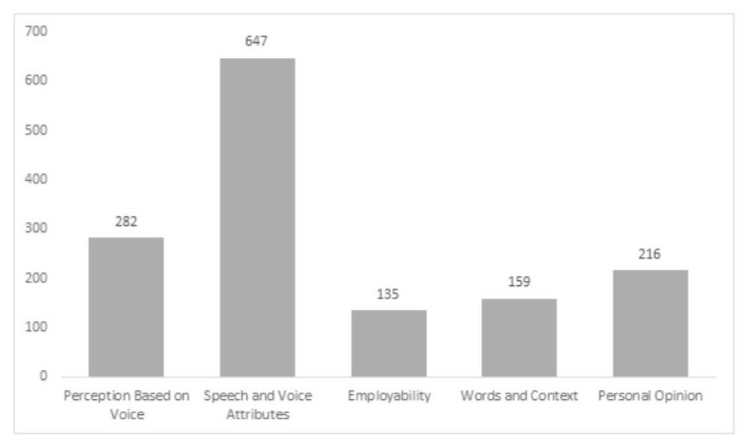

Four prompts were provided during the focus groups: explanation of ratings, descriptions and characteristics, time affect, and other information. Responses from each prompt were coded into the same themes utilized for the open text box responses. Each theme was noted across all prompts and all alaryngeal communication modalities with the exception of the theme personal opinion on the other information prompt during EL focus groups. Overall, the explanation of ratings, and descriptions and characteristics prompts resulted in the most discussion by contributing to a combined 80.9% of coded responses. Figure 2 provides further information on responses received during focus groups.

Figure 2: Focus group responses from each theme category for all prompts.

Prompt 1: Explanation of Ratings

Overall, 45.8% of focus group coded responses came from this prompt. 14.8% of responses were categorized into theme 1, 27.9% fell into theme 2, theme 3 accounted for 21.7% of responses, 17.5% of responses were categorized into theme 4, and the remaining 17.9% were theme 5. When investigating this prompt based on communication modality, each modality had a different theme capture the most results. During the ES focus groups, speech and voice attributes was most coded while personal opinion was coded most frequently during the EL focus groups and employability was the most coded theme during TES focus groups. Of interest is that the theme coded the least amount during the TES focus groups, personal opinion, was coded most frequently during EL focus groups. Also noteworthy is that the words and context was coded similarly for ES and TES, 12.5% and 12.2% respectively, but double the amount for the EL focus group, 25.9%.

Prompt 2: Descriptions and Characteristics

This prompt generated the second most responses with 35.1% of the responses. When looking at categorization of responses the greatest number of responses fell into theme 2, 38.3%. This was followed with the other categories having relatively similar amounts of responses, theme 1 (14.9%), theme 3 (16.2%), theme 4 (12.2%), and theme 5 (18.5%). When investigating this prompt based on communication modality, each modality captured the most responses in the speech and voice attributes theme.

Prompt 3: Time Affect

Approximately 12% of the focus group coded responses came from this prompt. Nearly half, 47.4%, of the responses were categorized into theme 5. Theme 2 and theme 4 resulted in the same number of responses, 17.1%. Employability and perception based on voice had the fewest responses with 10.5% and 7.9% respectively. When investigating this prompt based on communication modality, each modality had the highest number of responses categorized to theme 5. The ES focus group had a tie for the most responses between theme 5 and theme 2. Interestingly, the ES focus group had no responses categorized in theme 1 or 4 for this prompt.

Prompt 4: Other Information

Overall, 7.1% of focus group coded responses came from this prompt. 13.3% of responses were categorized into theme 1, 22.2% accounted for both theme 2 and theme 5, theme 3 accounted for 26.7% of responses, and the remaining 15.6% of responses were categorized into theme 4. When investigating this prompt based on communication modality, the ES and EL focus groups had the same categories capture the most results, speech and voice attributes. The TES focus group had a tie for the most responses from this prompt between employability and personal opinion. Of interest is that the EL focus group had no responses categorized in theme 5 for this prompt.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate listener impressions of alaryngeal communication modalities specifically as it pertains to employable attributes. Forty-five participants rated audio samples consisting of three alaryngeal communication modalities, ES, EL, and TES. Acoustic analysis demonstrated no significant differences between the speech stimuli or speaker sex. Significant differences were noted, however, regarding pitch and noise-to-harmonic ratio between the communication modalities. Overall results from visual analog ratings demonstrated a statistically significant difference between the three communication modalities. Open text box comments demonstrated that listeners made a significant number of comments regarding speech and voice attributes, while the other four categories each accounted for 20% of less of the total comments. Similarly, focus group discussions resulted in a large number of comments regarding speech and voice attributes, and personal opinion.

Previous research including impressions from lay public listeners noted favorable ratings for alaryngeal communication modalities other than TES [5]. Results from the current study, which also included participants outside of speech-language pathology, appear to support this notion as well. While these results should not be overgeneralized, this pattern of participants not solely connected to the field of communication disorders is interesting and may speak to the notion that individuals trained to support communication disorders have different standards or ways of thinking about verbal communication when compared to individuals in other areas. Current study overall results note mean EL scores to be significantly higher than TES or ES. Additionally, there was a significant difference amongst the contexts of employability statements. Each statement followed the same pattern of mean ratings, EL-TES-ES, regardless if a more general employment statement (I would hire this person for employment, I would take on this person for a job) or more direct (This person would be my first choice to hire after an interview) was posed. However, the range of ratings differed depending on the general or direct context of the statement.

Clinical Implications

Laryngeal cancer is one of the most common cancers of the upper aerodigestive tract. Professionals working in this area must take a whole-person approach as this diagnosis has significant implications on communication and quality of life. Speechlanguage pathologists should present and consider all alaryngeal communication modalities. There are several factors that go into pairing an individual with a successful communication modality and it is imperative that professionals remember the direct link communication has to quality of life. Thematic results from the current study note many comments related to speech and voice attributes. While these results should not be overgeneralized, speech-language pathologists should consider addressing factors such as respiration, muscle strength and endurance, and movement of the articulators to support effective communication. It is imperative to note that audio samples selected for this study were noted to be proficient speakers. Given the prevalence of laryngeal cancer this may highlight the need for increased education and training for speech-language pathologists in this area. Worth noting are the open text responses that may potentially be linked to the listener’s education and experiences. For example, comments linking a voice to smoking or elevating certain words that were spoken. Even after extensive therapy, there are characteristics of verbal alaryngeal communication that will remain atypical. Speechlanguage pathologists are in a unique position to provide education that may support more positive interactions and impressions of atypical vocal attributes. By enhancing professional education and training, more speech-language pathologists will be able to fully support individuals who receive a total laryngectomy and require an alaryngeal communication modality.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study is not without limitations. The first limitation worth noting is the listening environment of the participants. Due to a health pandemic and restrictions in place, in person data collection was not an option. Therefore, the exact environment in which participants sat during the data collection portion of the study is unknown and was not controlled by the research personnel. While researchers made every attempt to provide directives for an optimal participation environment, this should be taken into consideration when designing future studies. Secondly, participants were active university students. These individuals may not currently, or ever, be in a position to make hiring decisions.

Mean ratings on the visual analog scales did not move much beyond the halfway mark, indicating that there is still work that needs to be done in understanding what makes a voice ‘employable.’ Future studies should consider investigating attributes of laryngeal voices that categorize them as ‘highly employable’ and how these compare to alaryngeal communication modalities. Additionally, future research should consider including a variety of models of alaryngeal communication devices specifically within their design study and utilize participants that make hiring decisions or are on that career path trajectory.

Statements and Declarations

The author declares that no financial support was received to support the research detailed in this manuscript.

The author has no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the IRB at the University of Missouri.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge the contributions made by Cayce Gilbert, Rebecca Poulin, and Sarah Queen as graduate research assistants.

References

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A (2022) Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin 72: 7-33.

- Jazieh AR, Akbulut H, Curigliano G, Rogado A, Alsharm AA, et al. (2020) Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer care: A global collaborative study. JCO Glob Oncol 6: 1428-1438.

- Curry E, Snidecor J (1961) Physical measurement and pitch perception in esophageal speech. Laryngoscope 71: 415-424.

- Eadie T, Day A, Sawin D, Lamvik K, Doyle P (2013) Auditoryperceptual speech outcomes and quality of life after total laryngectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 148: 82-88.

- Knollhoff SM, Borrie SA, Barrett TS, Searl JP (2021) Listener impressions of alaryngeal communication modalities. Int J Speech Lang Pathol 23: 540-547.

- Evitts P, Van Dine A, Holler A (2009) Effects of audio-visual information and mode of speech on listener perceptions of alaryngeal speakers. Int J Speech Lang Pathol 11: 450-460.

- D’Alatri L, Bussu F, Scarano E, Paludetti G, Marchese M (2012) Objective and subjective assessment of tracheoesophageal prosthesis voice outcome. J Voice 26: 607-613.

- Nagle KF, Eadie TL (2012) Listener effort for highly intelligible tracheoesophageal speech. J Commun Disord 45: 235-245.

- Eadie TL, Bowker BC (2012) Coping and quality of life after total laryngectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 146: 959-965.

- Li X, Li J, Shi Y, Wang T, Zhang A, et al. (2017) Psychological intervention improves life quality of patients with laryngeal cancer. Patient Prefer Adherence 11: 1723-1727.

- Costa JM, López M, García J, León X, Quer M (2018) Impact of total laryngectomy on return to work. Acta Otorrinolaringologica (English Edition) 69: 74-79.

- Palmer AD, Graham MS (2004) The relationship between communication and quality of life in alaryngeal speakers. Canadian Journal of Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology 28: 6-24.

- Ramirez MJ, Ferriol EE, Domenech FG, Latas MC, Suarez-Varela MM, et al. (2003) Psychosocial adjustment in patients surgically treated for laryngeal cancer. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 129: 92-97.

- Callahan C (2005) Facial disfigurement and sense of self in head and neck cancer. Soc Work Health Care 40: 73-87.

- Lee JH, Ba D, Liu G, Leslie D, Zacharia BE, et al. (2019) Association of head and neck cancer with mental health disorders in a large insurance claims database. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 145: 339-344.

- Stone A, Wright T (2013) When your face doesn’t fit: Employment discrimination against people with facial disfigurements. J Appl Soc Psychol 43: 515-526.

- Jacobson JJ, Epstein JB, Eichmiller FC, Gibson TB, Carls GS, et al. (2012) The cost burden of oral, oral pharyngeal, and salivary gland cancers in three groups: Commercial insurance, Medicare, and Medicaid. Head Neck Oncol 4: 15.

- Lu L, O’Sullivan E, Sharp L (2019) Cancer-related financial hardship among head and neck cancer survivors: Risk factory and associations with health-related quality of life. Psychooncology 28: 863-871.

- Mott NM, Mierzwa ML, Casper KA, Shah JL, Mallen-St. Clair J, et al. (2022) Financial hardship in patients with head and neck cancer. JCO Oncol Pract 18: e925-e937.

- Kent EE, Forsythe LP, Yabroff KR, Weaver KE, de Morr JD, et al. (2013) Are survivors who report cancer-related financial problems more likely to forgo or delay medical care? Cancer 119: 3710-3717.

- Taylor JC, Terrell JE, Ronis DL, Fowler KE, Biship C, et al. (2004) Disability in patients with head and neck cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 130: 764-769.

- Allegra E, LaMantia I, Bianco MR, Drago GD, LeFosse MC, et al. (2019) Verbal performance of total laryngectomized patients rehabilitated with esophageal speech and tracheoesophageal speech: Impacts on patient quality of life. Psychol Res Behav Manag 12: 675-681.

- Suzuki M (2012) Quality of life, uncertainty, and perceived involvement in decision making in patients with head and neck cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 39: 541-548.

- Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, Van Bleek WJ, Leemans CR, de Bree R (2010) Employment and return to work in head and neck cancer survivors. Oral Oncol 46: 56-60.

- Bjordal K, Ahlner-Elmqvist M, Hammerlid E, Boysen M, Evensen JF, et al. (2001) A prospective study of quality of life in head and neck cancer patients. Part II: Longitudinal data. Laryngoscope 111: 1440-1452.

- Meropol NJ, Schrag D, Smith TJ, Mulvey TM, Langdon Jr RM, et al. (2009) American Society of Clinical Oncology guidance statement: The cost of cancer care. J Clin Oncol 27: 3868-3874.

- Osazuma-Peters N, Simpson MC, Zhao L, Boakye EA, Olomukoro SI, et al. (2018) Suicide risk among cancer survivors: head and neck versus other cancers. Cancer 124: 4072-4079.

- Altice CK, Banega MP, Tucker-Seeley RB, Yabroff KR (2017) Financial hardships experienced by cancer survivors: A systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst 109: djw205.

- Pearce AM, Timmons A, Hanly P, O’Neill C, Sharp L (2013) Workforce participation and productivity losses after head and neck cancer. Value Health 16: A418.

- Sharp L, Timmons A (2010) The financial impact of a cancer diagnosis. National Cancer Registry.

- Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77-101.

- Braun V, Clarke V (2012) Thematic analysis. In: Cooper H, Camic PM, Long DL, Panter AT, Rindskopf D, et al. (Eds.), APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, Vol. 2: Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological (pp 5771). American Psychological Association.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.