Efficacy and Safety of Bacopa monnieri Extract for Stress Management and Sleep Quality: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial

by Shashank Srinivas Gowda1, Lincy Joshua2, Jestin V. Thomas2*

1BGS Global Institute of Medical Sciences, No. 67, BGS Health and Education City, Uttarahalli Road, Kengeri, Bengaluru 560060, Karnataka, India

2Leads Clinical Research and Bio Services Pvt. Ltd., No. 9, 1st Floor Mythri Legacy, Kalyan Nagar, Chelekere Main Road, Bengaluru 560043, Karnataka, India

*Corresponding author: Jestin V. Thomas, Leads Clinical Research and Bio Services Pvt. Ltd., No. 9, 1st Floor Mythri Legacy, Kalyan Nagar, Chelekere Main Road, Bengaluru 560043, Karnataka, India.

Received Date: 23 January 2026

Accepted Date: 29 January 2026

Published Date: 2 February 2026

Citation: Gowda SS, Joshua L, Thomas JV (2026) Efficacy and Safety of Bacopa monnieri Extract for Stress Management and Sleep Quality: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Curr Res Cmpl Alt Med 10: 280. https://doi.org/10.29011/25772201.100280

Abstract

Background: Chronic psycho-social stress is associated with dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, impaired sleep, and adverse mood outcomes. Bacopa monnieri is an established adaptogen with potential benefits on stress and cognitive-emotional functioning. This study evaluated the efficacy and safety of B-Lit Bacopa (BME), a Bio Enhanced B. monnieri extract, in adults experiencing non-chronic stress. Methods: In this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial, 50 adults with non-chronic stress were assigned to receive BME (n=25) or placebo (n=25) once daily for 84 days. Validated psychometric assessments (Perceived Stress Scale-10 (PSS-10), Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Profile of Mood States (POMS), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), wrist actigraphy (sleep latency, actual sleep time, sleep efficiency, wake episodes, wake after sleep onset (WASO)), and serum cortisol were measured at baseline and designated time points over 12 weeks. Safety was monitored through adverse events, vitals, physical examination, and laboratory analyses. Results: Forty-four subjects completed the study. BME produced significant improvements in perceived stress starting from baseline at Day 14

(−2.48 ± 2.76 vs −1.10 ± 1.38; p<0.05), with progressive reductions through Day 84 (−6.30 ± 2.79 vs −0.38 ± 1.96; p<0.0001) compared to placebo. PSQI scores improved significantly by Day 28 (−2.74 ± 1.91 vs −0.43 ± 2.87; p<0.01) with pronounced effect on Day 84 (−3.70 ± 2.25 vs −0.52 ± 3.44; p<0.001) compared to placebo. POMS-Total Mood Disturbance score declined significantly starting Day 28 with marked reduction at Day 84 (−13.13 ± 8.34 vs −1.76 ± 1.48; p<0.0001). Anxiety symptoms (BAI) decreased significantly from Day 28 onward, reaching Day 84 values of −6.22 ± 3.88 vs −0.33 ± 2.20; p<0.0001 in comparison to placebo. Wrist actigraphy revealed increased actual sleep time (27.61 ± 41.44 vs −5.52 ± 24.61 min; p<0.01), and improved sleep efficiency (5.88 ± 7.91% vs −0.36 ± 5.25%; p<0.01) compared to placebo. No significant differences were noted from baseline for wake episodes and WASO compared to placebo. Serum cortisol declined significantly with BME compared with placebo (−4.10 ± 0.57 vs +0.27 ± 0.27 µg/dL; p<0.0001). There were 14 AEs reported by 08 subjects during the study period, all adverse events were mild and unrelated to BME. Conclusion: BME significantly improved stress, mood, anxiety, sleep quality, actigraphy-derived sleep parameters, and serum cortisol levels over 12 weeks supplementation and was well tolerated. It may offer a safe, effective approach for managing non-chronic stress.

Keywords: Bacopa monnieri; BME; Stress; Sleep quality; Actigraphy; Cortisol; Anxiety

Abbreviations: AE – adverse event; BAI – Beck Anxiety Inventory; BMI – body mass index; BEAT Tech™ – Bio Enhanced Active Technology; CONSORT – Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials; HPA – hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal; POMS – Profile of Mood States; TMD – Total Mood Disturbance; PSQI – Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; PSS – Perceived Stress Scale; SAE – serious adverse event; SE – standard error; WASO – wake after sleep onset.

Clinical Trials Registry - India, identifier: CTRI/2025/05/087114.

Introduction

Stress represents a fundamental biological response to internal or external demands and is governed by a complex interplay of physiological and neuroendocrine pathways that support body’s response under acute threat. While short-lived stress responses may serve adaptive functions, sustained or recurrent activation of these pathways contributes to a wide spectrum of adverse health outcomes, including hypertension, cardiovascular dysregulation, cognitive impairment, anxiety, depression, gastrointestinal disturbances, and immune dysfunction [1-5]. Modern lifestyles, psycho-social pressures, and environmental exposures have collectively contributed to increasing rates of chronic stress, leading to heightened interest in interventions capable of restoring homeostasis and preventing stress-related pathology [6,7].

Stress can be categorized into acute and chronic forms. Acute stress produces transient physiological changes that typically resolve once the stressor is removed and homeostasis is restored. In contrast, chronic or persistent stress leads to prolonged dysregulation of major neurobiological systems, including the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, resulting in irreparable alterations such as metabolic disturbances, anxiety disorders, visceral adiposity, and impaired cardio-metabolic and endocrine function [4,5,8]. Conventional medications for stress and anxiety management remain widely used, but long-term administration is often associated with dependence or withdrawalrelated concerns, underscoring the need for safer and more holistic alternatives [9,10].

Adaptogens are natural agents that enhance an individual’s capacity to respond to physical and psychological stressors by modulating physiological processes without disturbing normal biological function. An ideal adaptogen should demonstrate stress-protective activity, possess a favourable safety profile, support energy and cognitive function, and exhibit no addictive potential [11,12]. Adaptogens such as Bacopa monnieri (Brahmi) are believed to mediate their effects through modulation of the HPA axis and regulatory influence on key mediators of the stress response, including cortisol, nitric oxide, heat shock proteins, and stress-activated protein kinases [11].

B. monnieri is an Ayurvedic medicinal herb extensively recognized for its nootropic, anxiolytic, and adaptogenic properties. The phytochemical profile of Bacopa includes triterpenoid saponins (notably bacosides), alkaloids, flavonoids, glycosides, and other bioactive constituents, which contribute to its broad pharmacological actions [13-15]. Mechanistic evidence suggests that Bacopa supports cognitive and emotional health through antioxidant neuroprotection, cholinergic modulation, β-amyloid reduction, enhanced cerebral blood flow, and regulation of neurotransmitter systems including acetylcholine, dopamine, and serotonin [13,16,17]. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that standardized Bacopa extracts attenuate stress-induced elevations in plasma corticosterone, normalize monoamine levels in stressvulnerable brain regions, reduce stress-related physiological damage, and exert potent adaptogenic effects in both acute and chronic stress models [18,19]. Toxicological investigations further support the high therapeutic index and long-term safety of Bacopa, with no significant adverse findings at doses far exceeding typical human intake [20].

Clinical studies have shown that Bacopa supplementation improves memory, attention, working memory, and cognitive processing speed while also reducing anxiety, cortisol levels, and psychological distress [21-26]. Additional trials have demonstrated acute cognitive enhancement during demanding multitasking paradigms, early improvements in attention and mental flexibility, and reductions in perceived stress and mood disturbances following Bacopa administration [22,23]. Broader populationbased evidence, including studies conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, suggests significant reductions in depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms with Bacopa supplementation, supporting its relevance for modern stress-related health challenges [24]. Furthermore, clinical trials in elderly adults have reported improvements in delayed recall, attentional control, and anxiety levels, reinforcing its potential across diverse age groups [25].

BME is a proprietary B. monnieri formulation developed using Bio Enhanced Active Technology (BEAT Tech™), a solventfree delivery platform designed to enhance absorption and bioavailability. Substantial preclinical and clinical evidence supports the cognitive, emotional, and adaptogenic benefits of Bacopa extracts [21]. Building on this evidence, BME was developed to support multiple domains of brain health, including memory, attention, stress regulation, anxiety, and sleep quality. In an earlier randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group clinical study (B-Lit Bacopa efficacy study), a standardized B. monnieri extract administered at 300 mg/day (90 mg total bacosides) for 12 weeks in healthy adults demonstrated significant improvements in memory and cognitive performance compared with placebo. Improvements were observed across key memory and cognitive domains, with effects emerging within the early weeks of supplementation, alongside improvements in anxiety and sleep quality and favorable changes in stress and neuroplasticity-related biomarkers, while confirming good safety and tolerability. These findings provided the clinical rationale for the dose selection, intervention duration, and multidomain outcome measures employed in the present study [21].

Despite substantial traditional and scientific evidence supporting the adaptogenic and neurocognitive benefits of Bacopa, limited clinical studies have examined standardized formulations for acute and short-term stress in otherwise healthy adults. Given the rising prevalence of stress and sleep disturbances and the limitations of conventional pharmacotherapy, further research is necessary to validate the efficacy and safety of enhanced Bacopa formulations using modern clinical methodologies [27]. The current study was designed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of BME on stress and sleep outcomes in adults experiencing non-chronic stress, using validated psychometric measures for stress, sleep, mood, and anxiety, as well as objective assessments of sleep and serum cortisol to establish its therapeutic potential.

Methods

Study design and overview

This prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, two-arm, parallel-group clinical study evaluated the safety and efficacy of BME versus matched placebo in adults with nonchronic stress. The clinical phase for each participant lasted approximately 90 days and included a 5-day Baseline visit that included screening period (Day −5 to Day 0), a 12-week treatment period (Day 1 to Day 84), and scheduled follow-up visits. The study was conducted after Institutional Ethics Committee of BGS Global Institute of Medical Sciences, Bengaluru, India, approval and in accordance with the International Council for Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines, the Declaration of Helsinki, and applicable local regulations. The trial was registered with the Clinical Trials Registry - India, prior to first subject enrolment (CTRI/2025/05/087114).

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Subjects who met all of the following criteria were included in the study. Healthy adults aged 18–60 years with body mass index 18.5–29.9 kg/m², experiencing non-chronic stress of ≤12 weeks duration, scoring ≥10 and ≤26 on the perceived stress score (PSS10), without reported psychiatric diagnoses, willing and able to give informed consent, prepared to discontinue other herbal supplements or mood-altering preparations for the study duration, and able to comply with study restrictions (abstain from alcohol 24 hours prior to visits, avoid vigorous exercise for 12 hours prior to visits, and avoid caffeine 12 hours prior to visits). Female subjects of childbearing potential were required to use acceptable contraception and have negative urine pregnancy tests at screening and end of the study.

Exclusion criteria

Subjects who met any of the following criteria were excluded. Severe stress (PSS-10 ≥27); known hypersensitivity to Bacopa or excipients; history of cardiovascular, neurological, hepatic, renal, gastrointestinal, or other uncontrolled metabolic disease that could confound outcomes; diagnosed psychiatric illness (including major depression or anxiety disorders); uncontrolled hypertension (systolic blood pressure >160 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure >100 mmHg) at screening; current substance or alcohol abuse; pregnancy or breastfeeding; participation in another investigational study within 3 months prior to enrolment; or clinically significant laboratory abnormalities at screening.

Study procedures

Subjects were enrolled only after providing written informed consent. Screening procedures (Day −5 to 0) included medical history, concomitant medication review, physical examination, vital signs, anthropometrics, PSS-10, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) global score, Profile of Mood States (POMS), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) score, and laboratory safety tests (complete blood count, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, serum creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, and serum cortisol). Baseline objective sleep was assessed by housing subjects and collecting wrist actigraphy data for two consecutive nights (Day −1 to 0). Eligible subjects returned fasting for randomization on Day 1.

Study visits and procedures

Participants attended six clinic visits: screening/baseline visit (Day

−5 to 0; housing Day −1 to 0), randomization (Day 1), follow-up 1 (Day 14 ± 3), follow-up 2 (Day 28 ± 3), follow-up 3 (Day 56 ± 3), and end of study (Day 84 ± 3; housing Day 83–84). At scheduled visits study procedures included physical examination, vital signs, concomitant medication review, adverse event monitoring, investigational product accountability, and administration of questionnaires (PSS-10, PSQI, POMS-40, BAI) per schedule. Wrist actigraphy was collected at screening visit (two nights Days -1 and 0) and repeated at the end of the study (two nights Days 83–84) and averaged for analysis. Fasting blood samples for serum cortisol and safety laboratories were collected at screening and end of study.

Randomization and blinding

After confirmation of eligibility, subjects were randomized ratio 1:1 to BME or placebo using a computer-generated randomization schedule. Allocation was provided as unique randomization numbers. Blinding was maintained by dispensing identically appearing coded capsules; the independent dispenser had no role in efficacy or safety assessments. Investigators, site staff performing assessments, and participants remained blinded throughout the study.

Investigational product and dosing

The test product, BME, contained B. monnieri extract standardized to 30% total bacosides (commercially known as B-Lit Bacopa®) per capsule of 500 mg (300 mg BME extract with 200 mg microcrystalline cellulose). The placebo consisted of 500 mg microcrystalline cellulose in identical capsules. Subjects selfadministered one capsule orally each morning after breakfast at a consistent time for 84 consecutive days. Both the capsules were manufactured by Samriddh Nutractive Private Limited, India.

Safety monitoring

Safety assessments included monitoring and recording of all adverse events and serious adverse events, physical examinations, vital signs, and laboratory evaluations. Adverse events (AEs) were documented with onset, duration, intensity, causality, action taken, and outcome. Serious adverse events (SAEs) were reported per regulatory requirements and followed until resolution.

Efficacy endpoints

Efficacy endpoint included mean change from baseline in PSS10, PSQI, POMS total, and BAI score evaluated at, baseline, Day 14, Day 28, Day 56, and Day 84 comparing BME to placebo. Wrist actigraphy-derived sleep parameters (sleep latency, total sleep time, sleep efficiency, wake episodes, wake after sleep onset (WASO)), and serum cortisol were compared from baseline to Day 84.

Perceived Stress Scale

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) is a 10-item questionnaire developed by Cohen et al. (1983) to assess the degree to which individuals appraise situations in their lives as stressful [28]. It is brief, easy to administer, and demonstrates strong reliability and validity. PSS-10 scoring involves reversing four positively worded items (items 4, 5, 7, and 8) and summing all items [28-30].

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) is a validated tool for assessing sleep quality and patterns over the past month. It evaluates seven components—subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction—each rated on a 0–3 scale. Component scores are summed to yield a global score, with values ≥5 indicating poor sleep quality [31,32].

Profile of Mood States

The Profile of Mood States (POMS) is a validated psychological rating scale developed by McNair et al. (1971) to assess transient mood states [33]. The revised 40-item version measures seven domains: tension, depression, fatigue, vigor, confusion, anger, and esteem-related affect. Participants rate each adjective on a 0–4 scale (“Not at all” to “Extremely”). This abbreviated POMS is simple to administer, easy for participants to understand, and has demonstrated acceptable reliability and validity in clinical and sport psychology research [33,34].

Beck Anxiety Inventory

The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) is a 21-item self-report measure assessing common anxiety symptoms. Each item is rated on a 0–3 scale based on how the respondent has felt over the past week, yielding a total score from 0 to 63. Scores are classified as minimal (0–7), mild (8–15), moderate (16–25), or severe anxiety (26–63). The BAI has demonstrated strong psychometric properties and is widely used in both clinical and research settings [35,36].

Wrist actigraphy

Wrist actigraphy provides an objective estimate of sleep–wake patterns by recording movement data that are analyzed using validated algorithms. It offers the advantage of continuous, noninvasive monitoring in the participant’s natural sleep environment and has been validated for assessing nocturnal sleep parameters across age groups. Actigraphy is commonly used to document sleep patterns, evaluate circadian rhythm disorders, assess treatment responses, and support home-based sleep monitoring. In this study, participants wore a wrist actigraphy device (MotionWatch 8, CamNtech Ltd. [United Kingdom] continuously for 2 days according to the study schedule, and data were downloaded for standard sleep–wake analysis [37,38].

Serum cortisol

Serum cortisol is a widely used biochemical marker of HPA axis activity and physiological stress. Cortisol levels follow a diurnal rhythm, typically peaking in the early morning and declining throughout the day. Quantification is performed using standardized immunoassay or chemiluminescence methods, providing an objective index of basal stress physiology. In this study, fasting morning serum cortisol was measured according to the study schedule to assess participants’ HPA axis activity [39,40]. Serum cortisol was measured using the Beckman Coulter Access2 by Chemiluminescence Immunoassay.

Safety endpoints

Safety endpoints included clinically significant changes in laboratory parameters, incidence and severity of AEs/SAEs, and clinically relevant changes in vital signs or physical examination findings.

Sample size determination

Fifty subjects (25 per arm) were planned to provide approximately 80% power to detect a clinically meaningful between-group difference on the primary endpoint at a two-sided alpha = 0.05, allowing for an anticipated dropout rate of ~10%. The assumptions and calculations are documented in the study files.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R statistical software 4.2.1. Demographic and baseline characteristics were summarized by randomized group and overall. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± SE; categorical variables were presented as counts and percentages. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. For normally distributed continuous outcomes, between-group comparisons used two-sample t-tests or ANOVA models as appropriate; within-group changes used paired t-tests. Non-parametric alternatives (Mann–Whitney U test, Wilcoxon signed-rank) were used when distributional assumptions are not met. Categorical variables were compared using chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests. All hypothesis tests are two-sided with alpha = 0.05. Efficacy analyses were conducted on the randomized studycompleted population; safety analyses on the safety population (all randomized subjects who received any investigational product).

Any deviations from planned methods were documented in the clinical study report.

Results

Participant Characteristics

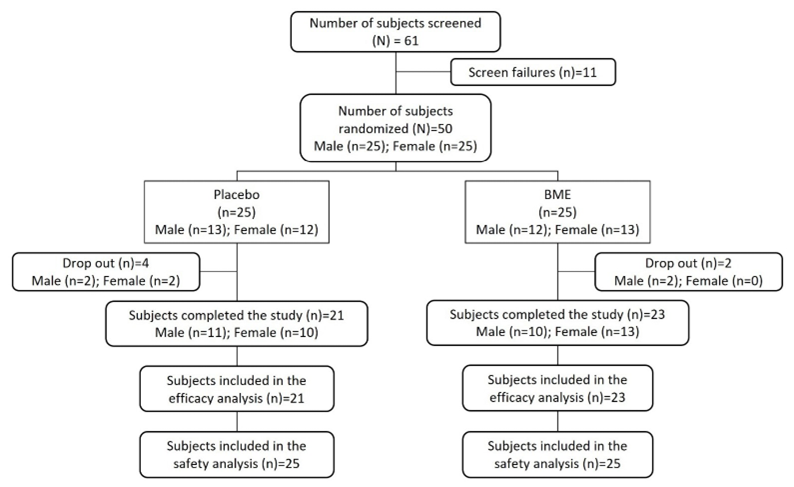

A total of 61 individuals were screened, of whom 50 met the eligibility criteria and were randomized in a parallel-group design to receive either BME (n = 25; male = 12, female = 13) or placebo (n = 25; male = 13, female = 12) (Fig. 1). Eleven individuals did not meet screening criteria and were not enrolled. Over the 12week intervention period, six participants discontinued: four from the placebo group (male = 2, female = 2) and two from the BME group (male = 2). A total of 44 participants completed the study (BME: n = 23; placebo: n = 21) and were included in the efficacy analyses, while all 50 randomized participants were included in the safety analyses.

The mean (±SE) age of participants was 38.83 ± 2.01 years in the

BME group and 36.52 ± 2.12 years in the placebo group (Table 1). The mean (±SE) height was 162.35 ± 1.96 cm and 161.86 ±

1.74 cm, and the mean (±SE) body weight was 65.44±1.22 kg and 64.28±1.31 kg, respectively, in the BME and placebo groups. Body mass index values were comparable between groups (24.96 ± 0.58 kg/m² for BME vs 24.57±0.47 kg/m²). All baseline demographic and anthropometric measurements were similar between treatment groups (p>0.05), indicating successful randomization.

Figure 1: Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram of participant disposition.

|

Parameter |

Placebo (N=21) Mean ± SE |

BME (N=23) Mean ± SE |

|

Age (years) |

36.52 ± 2.12 |

38.83 ± 2.01 |

|

Height (cm) |

161.86 ± 1.74 |

162.35 ± 1.96 |

|

Body Weight (kg) |

64.28 ± 1.31 |

65.44 ± 1.22 |

|

Body Mass Index (kg/m²) |

24.57 ± 0.47 |

24.96 ± 0.58 |

|

Notes: Values are presented as mean ± standard error (SE). Baseline characteristics were assessed prior to randomization. BMI = body mass index; kg/m² = kilograms per square meter. |

||

Table 1: Baseline Demographic and Anthropometric Characteristics of Participants in the BME and Placebo Groups.

Efficacy endpoints - Primary efficacy endpoint

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)

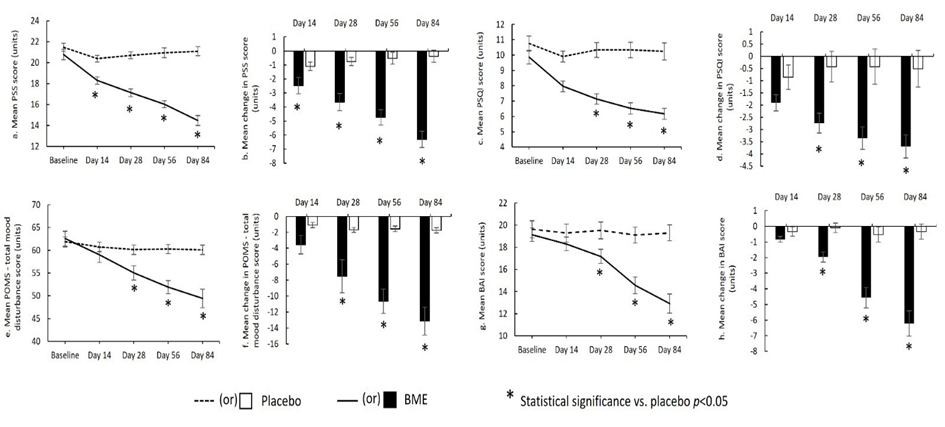

The primary efficacy endpoint was mean change in perceived stress, measured using the PSS-10 (Fig. 2a&b; Table 2a&b). By Day 14, the mean change from baseline was −2.48 ± 0.58 in the BME group compared with −1.10 ± 0.30 in the placebo group (p = 0.0450). By Day 28, changes reached −3.65 ± 0.61 and −0.76 ± 0.29, respectively (p = 0.0002). Reductions continued through Day 56, with changes of −4.74 ± 0.55 for BME and −0.52 ± 0.43 for placebo (p < 0.0001). At Day 84, the BME group achieved its largest reduction, with a mean change of −6.30 ± 0.58 compared with −0.38 ± 0.43 in the placebo arm (p < 0.0001). These findings indicate a sustained and progressively increasing treatment effect over the 84-day period.

Efficacy endpoints - Secondary efficacy endpoints

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)

The mean change in PSQI score was −1.91 ± 0.33 in the BME group and −0.86 ± 0.50 in the placebo group (p = 0.0810) by Day 14, (Fig. 2c&d; Table 2c&d). By Day 28, reductions were −2.74 ± 0.40 and −0.43 ± 0.63, respectively (p = 0.0030). Continued improvement was evident by Day 56, with changes of −3.35 ± 0.46 for BME and −0.43 ± 0.72 for placebo (p = 0.0010). At Day 84, the BME group showed the largest reduction in PSQI, with a mean change of −3.70 ± 0.47 compared with −0.52 ± 0.75 for placebo (p = 0.0007). These findings indicate a progressive and statistically significant improvement in sleep quality with BME over 84 days.

Profile of Mood States (POMS) – Total Mood Disturbance (TMD) score

Mood state, assessed using the POMS-40, demonstrated broad improvements across total mood disturbance and all sub-scales (Fig. 2e&f; Table 2e&f). By Day 14, the mean change was −3.57 ± 1.16 in the BME group and −1.10 ± 0.34 in the placebo group (p = 0.0570). By Day 28, reductions were −7.52 ± 2.08 for BME and −1.71 ± 0.32 for placebo (p = 0.0120). Continued improvement was observed at Day 56, with changes of −10.65 ± 1.54 versus −1.57 ± 0.34 (p = 0.0000). By Day 84, the BME group exhibited the greatest reduction in POMS-TMD, with a mean change of −13.13 ± 1.74 compared with −1.76 ± 0.32 in the placebo group (p = 0.0000). These findings indicate a progressive and statistically significant reduction in mood disturbance across the 84-day period with BME.

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI)

Anxiety symptoms, assessed by the BAI, decreased significantly in both groups but to a markedly greater extent with BME (Fig. 2g&h; Table 2g&h). By Day 14, the mean change was −0.83 ± 0.18 in the BME group and −0.33 ± 0.31 in the placebo group (p

= 0.1720) (Fig. 2h; Table 2h). By Day 28, reductions were −1.96 ± 0.33 versus −0.10 ± 0.30 (p = 0.0002). Continued improvement was observed at Day 56, with changes of −4.57 ± 0.66 compared with −0.52 ± 0.49 (p = 0.0000). By Day 84, the BME group exhibited the largest reduction in BAI, with a mean change of −6.22 ± 0.81 versus −0.33 ± 0.48 in the placebo arm (p = 0.0000). These results indicate a progressive and statistically significant reduction in anxiety symptoms over 84 days with BME.

Figure 2: Psychological outcome measures in the BME and placebo groups over the 84-day intervention: (a) mean Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) score; (b) mean change in PSS score; (c) mean Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) score; (d) mean change in PSQI score; (e) mean Profile of Mood States – Total Mood Disturbance (POMS-TMD) score; (f) mean change in POMS-TMD score; (g) mean Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) score; and (h) mean change in BAI score. p < 0.05 vs. placebo.

|

Visit/Δ |

Placebo (N=21) Mean ± SE |

BME (N=23) Mean ± SE |

Treatment Effect One-Way ANOVA (p-value) |

|

a. Perceived Stress Scale – Total Score |

|||

|

V1 (Baseline) |

21.48 ± 0.39 |

20.78 ± 0.49 |

0.2800 |

|

V2 (Day 14) |

20.38 ± 0.33 |

18.30 ± 0.35 |

0.0001* |

|

V3 (Day 28) |

20.71 ± 0.32 |

17.13 ± 0.37 |

0.0000* |

|

V4 (Day 56) |

20.95 ± 0.47 |

16.04 ± 0.33 |

0.0000* |

|

V5 (Day 84) |

21.10 ± 0.43 |

14.48 ± 0.46 |

0.0000* |

|

b. Change of Perceived Stress Scale – Total Score |

|||

|

V2–V1 |

−1.10 ± 0.30 |

−2.48 ± 0.58 |

0.0445* |

|

V3–V1 |

−0.76 ± 0.29 |

−3.65 ± 0.61 |

0.0002* |

|

V4–V1 |

−0.52 ± 0.43 |

−4.74 ± 0.55 |

0.0000* |

|

V5–V1 |

−0.38 ± 0.43 |

−6.30 ± 0.58 |

0.0000* |

|

c. Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index Total Score |

|||

|

V1 (Baseline) |

10.76 ± 0.49 |

9.87 ± 0.44 |

0.1830 |

|

V2 (Day 14) |

9.91 ± 0.36 |

7.96 ± 0.35 |

0.0004* |

|

V3 (Day 28) |

10.33 ± 0.48 |

7.13 ± 0.34 |

0.0000* |

|

V4 (Day 56) |

10.33 ± 0.51 |

6.52 ± 0.37 |

0.0000* |

|

V5 (Day 84) |

10.24 ± 0.56 |

6.17 ± 0.36 |

0.0000* |

|

d. Change of Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index Total Score |

|||

|

V2–V1 |

−0.86 ± 0.50 |

−1.91 ± 0.33 |

0.0806 |

|

V3–V1 |

−0.43 ± 0.63 |

−2.74 ± 0.40 |

0.0029* |

|

V4–V1 |

−0.43 ± 0.72 |

−3.35 ± 0.46 |

0.0012* |

|

V5–V1 |

−0.52 ± 0.75 |

−3.70 ± 0.47 |

0.0007* |

|

e. Profile of Mood States Total Mood Disturbances Score |

|||

|

V1 (Baseline) |

61.86 ± 1.09 |

62.57 ± 1.62 |

0.7240 |

|

V2 (Day 14) |

60.76 ± 1.07 |

59.00 ± 1.64 |

0.3820 |

|

V3 (Day 28) |

60.14 ± 1.03 |

55.04 ± 1.55 |

0.0100* |

|

V4 (Day 56) |

60.29 ± 1.01 |

51.91 ± 1.45 |

0.0000* |

|

V5 (Day 84) |

60.10 ± 1.03 |

49.44 ± 2.04 |

0.0000* |

|

f. Change of Profile of Mood States Total Mood Disturbances Score |

|||

|

V2–V1 |

−1.10 ± 0.34 |

−3.57 ± 1.16 |

0.0565 |

|

V3–V1 |

−1.71 ± 0.32 |

−7.52 ± 2.08 |

0.0117* |

|

V4–V1 |

−1.57 ± 0.34 |

−10.65 ± 1.54 |

0.0000* |

|

V5–V1 |

−1.76 ± 0.32 |

−13.13 ± 1.74 |

0.0000* |

|

g. Beck Anxiety Inventory Score |

|||

|

V1 (Baseline) |

19.62 ± 0.77 |

19.13 ± 0.60 |

0.6160 |

|

V2 (Day 14) |

19.29 ± 0.82 |

18.30 ± 0.62 |

0.3400 |

|

V3 (Day 28) |

19.52 ± 0.76 |

17.17 ± 0.65 |

0.0230* |

|

V4 (Day 56) |

19.10 ± 0.73 |

14.57 ± 0.76 |

0.0001* |

|

V5 (Day 84) |

19.29 ± 0.72 |

12.91 ± 0.86 |

0.0000* |

|

h. Change of Beck Anxiety Inventory Score |

|||

|

V2–V1 |

−0.33 ± 0.31 |

−0.83 ± 0.18 |

0.1720 |

|

V3–V1 |

−0.10 ± 0.30 |

−1.96 ± 0.33 |

0.0002* |

|

V4–V1 |

−0.52 ± 0.49 |

−4.57 ± 0.66 |

0.0000* |

|

V5–V1 |

−0.33 ± 0.48 |

−6.22 ± 0.81 |

0.0000* |

|

Notes: Values are mean ± standard error (SE). Treatment Effect (One-Way ANOVA p-value) indicates the between-group difference at each visit or change-from-baseline contrast. Between-Group Comparison (Bonferroni p-value) represents Bonferroni-adjusted pairwise comparisons for changefrom-baseline values. V1 = Baseline (Day −5 to 0); V2 = Day 14 ± 3; V3 = Day 28 ± 3; V4 = Day 56 ± 3; V5 = Day 84 ± 3. SE = standard error; V = visit; ANOVA = analysis of variance. *p < 0.05. |

|||

Table 2: Mean Scores and Change-from-Baseline Values for Stress (a & b), Sleep Quality (c & d), Mood Disturbance (e & f), and Anxiety (g & h) Across Visits in the BME and Placebo Groups.

Wrist Actigraphy

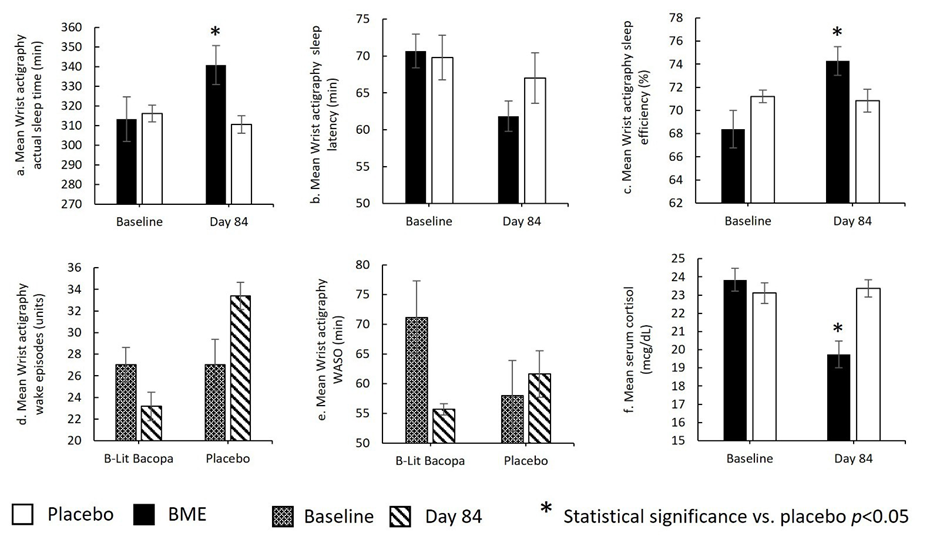

Actigraphy-derived sleep parameters showed consistent and clinically meaningful improvements in objective sleep architecture following BME supplementation (Fig 3a-e; Table 3a-e).

Actual sleep time (Min.)

The BME group showed a mean increase of 27.61 ± 8.64 minutes, whereas the placebo group showed a mean decrease of −5.52 ± 5.37 minutes (p = 0.0027) (Fig. 3a; Table 3a). Within-group analysis indicated that the increase from Day 1 to Day 84 was statistically significant in the BME group (p = 0.0042), while the placebo group showed no significant change over the same period (p = 0.3161). These findings suggest that BME meaningfully increased actual sleep duration across the 84-day intervention.

Sleep latency (Min.)

Change-from-baseline analyses showed a reduction of −8.84 ± 2.23 minutes in the BME group and −2.76 ± 4.75 minutes in the placebo group (p = 0.2398) (Fig. 3b; Table 3b). Within-group comparisons indicated that the reduction from Day 1 to Day 84 was statistically significant in the BME group (p = 0.0007), while the placebo group did not exhibit a significant change (p = 0.5675). These findings suggest that BME improved sleep latency over time, although between-group differences did not reach statistical significance.

Sleep efficiency (%)

The mean change from baseline to Day 84 was 5.88 ± 1.65% for BME and −0.36 ± 1.14% for placebo (p = 0.0039) (Fig. 3c; Table 3c). Within-group comparisons showed a significant increase in sleep efficiency from Day 1 to Day 84 in the BME group (p = 0.0017), whereas the placebo group did not show a significant change (p=0.7542). These results indicate a statistically significant improvement in sleep efficiency with BME over the 84-day intervention.

Wake episodes (Units)

The between-group comparison of change from baseline (Day 84 − Day 1) showed a mean change of −3.86 ± 3.17 for BME versus 6.35 ± 1.83 for placebo (p = 0.0093) (Fig. 3d; Table 3d). Within-group comparisons indicated the change from Day 1 to Day 84 was not statistically significant for BME (p = 0.2357) but was significant for placebo (p = 0.0024). These results indicate a significant between-group difference over 84 days, however the effect was not attributed to BME as there was no significant change compared to baseline.

WASO (minutes)

Change-from-baseline analyses showed a mean reduction of −15.45 ± 8.16 minutes in the BME group compared with an increase of 3.69 ± 4.17 minutes in the placebo group (p = 0.0487) (Fig. 3e; Table 3e). Within-group comparisons from Day 1 to Day 84 were not statistically significant for either group (BME p = 0.0715; placebo p = 0.3867). These results indicate a significant between-group difference over 84 days, however the effect was not attributed to BME as there was no significant change compared to baseline.

Serum cortisol (µg/dL)

Change-from-screening analysis showed a mean reduction of −4.10 ± 0.57 µg/dL in the BME group compared with a mean increase of 0.27 ± 0.27 µg/dL in the placebo group (p = 0.0000) (Fig. 3f; Table 3f). Within-group comparisons indicated that the reduction from screening to Day 84 was statistically significant in the BME group (p < 0.0001), while the placebo group showed no significant change over the same period (p = 0.3345). These results indicate that BME was associated with a significant decrease in serum cortisol over 84 days compared with placebo.

Figure 3: Wrist actigraphy–derived sleep parameters and serum cortisol levels in the BME and placebo groups at baseline and Day 84: (a) mean actual sleep time; (b) mean sleep latency; (c) mean sleep efficiency; (d) mean wake episodes; (e) mean wake after sleep onset (WASO); and (f) mean serum cortisol concentration. p < 0.05 vs. placebo.

|

Visit/Δ |

Placebo (N=21) Mean ± SE |

BME (N=23) Mean ± SE |

Independent t-test p-value |

Paired Sample t-Test |

|

a. Wrist Actigraphy - Actual Sleep Time (Minutes) |

||||

|

V1 (Baseline) |

V1 (Baseline) |

V1 (Baseline) |

V1 (Baseline) |

V1 (Baseline) |

|

V5 (Day 84) |

V5 (Day 84) |

V5 (Day 84) |

V5 (Day 84) |

V5 (Day 84) |

|

Δ V5–V1 |

Δ V5–V1 |

Δ V5–V1 |

Δ V5–V1 |

Δ V5–V1 |

|

b. Wrist Actigraphy - Sleep Latency (Minutes) |

||||

|

V1 (Baseline) |

V1 (Baseline) |

V1 (Baseline) |

V1 (Baseline) |

V1 (Baseline) |

|

V5 (Day 84) |

V5 (Day 84) |

V5 (Day 84) |

V5 (Day 84) |

V5 (Day 84) |

|

Δ V5–V1 |

Δ V5–V1 |

Δ V5–V1 |

Δ V5–V1 |

Δ V5–V1 |

|

c. Wrist Actigraphy - Sleep Efficiency (%) |

||||

|

V1 (Baseline) |

71.21 ± 0.54 |

68.39 ± 1.62 |

0.1195 |

- |

|

V5 (Day 84) |

70.85 ± 0.97 |

74.28 ± 1.23 |

0.0370* |

- |

|

Δ V5–V1 |

−0.36 ± 1.14 |

5.88 ± 1.65 |

0.0039* |

0.0017* (Bacopa); 0.7542 (Placebo) |

|

d. Wrist Actigraphy - Wake Episodes (units) |

||||

|

V1 (Baseline) |

27.02 ± 1.31 |

27.04 ± 1.60 |

0.9925 |

- |

|

V5 (Day 84) |

33.38 ± 1.26 |

23.17 ± 2.36 |

0.0006* |

- |

|

Δ V5–V1 |

6.35 ± 1.83 |

−3.86 ± 3.17 |

0.0093* |

0.2357 (Bacopa); 0.0024* (Placebo) |

|

e. Wrist Actigraphy - Wake After Sleep Onset (Minutes) |

||||

|

V1 (Baseline) |

57.97 ± 0.94 |

71.17 ± 6.16 |

0.0493* |

- |

|

V5 (Day 84) |

61.66 ± 3.92 |

55.71 ± 5.92 |

0.4165 |

- |

|

Δ V5–V1 |

3.69 ± 4.17 |

−15.45 ± 8.16 |

0.0487* |

0.0715 (Bacopa); 0.3867 (Placebo) |

|

f. Serum Cortisol (µg/dL) |

||||

|

V1 (Baseline) |

23.11 ± 0.57 |

23.84 ± 0.62 |

0.3847 |

- |

|

V5 (Day 84) |

23.37 ± 0.48 |

19.74 ± 0.74 |

0.0002* |

- |

|

Δ V5–V1 |

0.27 ± 0.27 |

−4.10 ± 0.57 |

0.0000* |

<0.0001* (Bacopa); 0.3345 (Placebo) |

|

Notes: Values are mean ± standard error (SE). Between-Group Comparison refers to independent sample t-test results (BME vs placebo). Paired Sample t-Test values indicate within-group changes from baseline (V1) to Day 84 (V5) and are shown separately for each group. V1 = Baseline (Day −5 to 0); V5 = Day 84 ± 3 days. µg/dL = micrograms per deciliter; Δ = change (V5–V1). *p < 0.05 indicates statistical significance. |

||||

Table 3: Wrist Actigraphy Measures (a–e) and Serum Cortisol (f) at Baseline and Day 84, and Change-from-Baseline Values in the BME and Placebo Groups.

Safety Endpoints

As summarized in Table 4, 8 of 50 participants (16%) experienced at least one AE, with 3 out of 25 (12%) in the BME group and 5 out of 25 (20%) in the placebo group. A total of 4 AEs occurred in the BME group compared with 10 in placebo. The most common AEs were fever (n=3) and headache (n = 3), all reported in the placebo group. Other events—including cold, viral fever, upper respiratory tract infection, gastritis, tiredness, and sore throat—were infrequent and reported as isolated cases. All AEs were mild in severity, investigator-assessed as unrelated to the investigational products, and resolved before study completion. No SAEs, withdrawals due to AEs, or deaths occurred. Additionally, no clinically significant changes were observed in vital signs or physical examination findings in either group. Overall, the investigational products demonstrated a favorable safety and tolerability profile comparable to placebo.

|

Adverse Events Term |

Placebo N=25 n (%) |

BME N=25 n (%) |

Overall N=50 n (%) |

|

Subjects with at least one AE |

5 (20%) |

3 (12%) |

8 (16%) |

|

Total AE’s |

10 |

4 |

14 |

|

Fever |

3 |

- |

3 |

|

Cold |

- |

1 |

1 |

|

Headache |

3 |

- |

3 |

|

Viral Fever |

- |

1 |

1 |

|

Gastritis |

1 |

- |

1 |

|

Tiredness |

2 |

- |

2 |

|

Upper Respiratory Tract Infection |

- |

1 |

1 |

|

Sore Throat |

1 |

1 |

2 |

|

Notes: Values are presented as number of subjects (n) and percentage (%). Percentages are based on the safety population: BME (N = 25), Placebo (N = 25), Overall (N = 50). Total AE count represents the total number of events, not the number of subjects. AE = adverse event. |

|||

Table 4: Summary of Adverse Events in the BME and Placebo Groups.

Discussion

The present randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study evaluated the effects of 12 weeks of BME supplementation on stress, sleep, mood state, anxiety, and serum cortisol in adults experiencing non-chronic stress. The findings demonstrate consistent, progressive, and clinically meaningful improvements across both subjective and objective outcomes, supporting the adaptogenic and anxiolytic potential of this enhanced B. monnieri formulation. The results align with the established pharmacological properties of Bacopa, including modulation of the HPA axis, neurochemical regulation, antioxidant activity, and support of cognitive-emotional resilience [11-19].

Perceived stress, assessed using the PSS-10, showed rapid and sustained reductions with BME beginning as early as Day 14 and continuing through Day 84. The magnitude of reduction, exceeding six points by the end of the intervention, is consistent with clinically meaningful improvement and surpasses changes expected from placebo responses alone [28-30]. These findings support previous evidence showing reductions in psychological stress and mood reactivity following standardized Bacopa supplementation [2224]. The improvement observed in the current study further aligns with the known time-dependent pharmacodynamics of Bacopa, where adaptogenic and psychophysiological benefits typically accumulate over weeks of continued use [13,15].

Sleep quality, quantified via PSQI, also improved significantly in the BME group, with early divergence from placebo by Day 14 and continual improvement over time. These results align with earlier reports of Bacopa improving subjective sleep quality, reducing sleep disturbances, and enhancing restorative sleep [24]. Importantly, the present study incorporated objective actigraphybased assessments that revealed improvements in actual sleep time, and sleep efficiency. These findings support the hypothesis that Bacopa’s stress-attenuating and anxiolytic effects may translate into measurable alterations in sleep architecture, possibly via modulation of cortisol and neurotransmitter pathways implicated in sleep regulation [11,13,19,37,38].

Mood disturbances measured by POMS-TMD also declined substantially with BME. Participants exhibited reductions across all major mood domains, consistent with earlier clinical studies demonstrating improvements in anxiety, tension, fatigue, and cognitive-emotional processing following Bacopa supplementation [21-26]. The profile of improvements suggests broad psychophysiological stabilization rather than isolated domain-specific effects, consistent with the adaptogenic framework described in previous literature [12,18].

Anxiety levels, measured by the Beck Anxiety Inventory, were significantly reduced in the BME group, with changes becoming significant by Day 28 and deepening through Day 84. These findings reinforce Bacopa’s anxiolytic properties observed in both animal and human studies [16,18,25,36]. Mechanistic explanations include restoration of monoaminergic balance, attenuation of oxidative stress, and moderation of cortisol-associated emotional reactivity [13,15,19].

Objective sleep assessments obtained through wrist actigraphy demonstrated consistent and clinically meaningful improvements in sleep architecture following BME supplementation (Fig. 3a–e). Participants receiving BME showed increased actual sleep time, and enhanced sleep efficiency,over the 84-day intervention. These findings extend previous work suggesting that Bacopa possesses adaptogenic and neuropsychological properties capable of reducing physiological arousal and promoting restorative sleep [12,13,15]. Mechanistically, Bacopa has been shown to modulate the HPA axis [18,19], attenuate stress-induced oxidative burden [15], and influence serotonergic and cholinergic pathways implicated in sleep regulation [13]. Such mechanisms may reduce nighttime hyperarousal, improve sleep continuity, and support the observed reductions in nocturnal awakenings. The convergence of objective actigraphy outcomes with subjective sleep improvements measured via the PSQI further reinforces the role of Bacopa in enhancing both perceived and physiological sleep quality [24,31,32].

Supplementation with BME produced a significant reduction in serum cortisol over the 84-day period, while cortisol levels in the placebo group remained unchanged. Cortisol is a primary biomarker of HPA-axis activation and is routinely used to index physiological stress load [1,2,5]. Elevated or dysregulated cortisol is associated with impaired mood, disrupted sleep, and emotional vulnerability [8,11]. The cortisol-lowering effect observed in the present study is consistent with previous experimental findings in which Bacopa normalized corticosterone levels and attenuated stress-induced neuroendocrine activation in animal models [18,19]. Improvements in perceived stress, anxiety, mood states, and sleep continuity observed in this trial likely reflect downstream benefits of more regulated HPA-axis activity. Taken together, these results support the hypothesis that Bacopa exerts adaptogenic effects through multimodal mechanisms involving glucocorticoid modulation, neurotransmitter stabilization, and antioxidative neuroprotection [12,13,15,18].

Compared with previous trials that used standard Bacopa extracts, the magnitude and consistency of improvements observed in this study may reflect the enhanced delivery characteristics of the BEAT Tech™ formulation. Limited bioavailability of saponins such as bacosides has been a known challenge in translating Bacopa’s pharmacological potential into clinical efficacy [13,15,41]. Enhanced absorption may therefore contribute to the early onset and cumulative effects documented here [21].

Collectively, these findings support the adaptogenic, anxiolytic, and sleep-modulating potential of BME for adults experiencing non-chronic stress. The multidimensional benefits observed across stress perception, mood, anxiety, sleep architecture, and cortisol suggest that this formulation may offer a holistic and safe therapeutic option for stress-related disturbances.

BME was well tolerated throughout the study, with adverse events being infrequent, mild in severity, and comparable to placebo (Table 4). No serious adverse events, discontinuations due to adverse events, or clinically significant abnormalities in vital signs or physical exams were observed. These findings are consistent with toxicological and clinical research indicating that B. monnieri is generally safe when administered at standard doses over extended periods [16,20,25,41]. The absence of cortisol-related adverse endocrine effects or sleep-disruptive symptoms further supports the safety profile of Bacopa in populations experiencing heightened stress [20,25,41]. Overall, the tolerability and AE profile observed in this study confirm that BME is safe for use in healthy adults with non-chronic stress.

The study population consisted of adults with non-chronic stress, which may limit applicability to individuals with clinical psychological disorders or insomnia. The 84-day duration does not determine whether effects persist long term or after discontinuation. However, the choice of 84 days was based on previous Bacopa trials showing cumulative effects within 8–12 weeks [25,26,42-44]. Outcomes were primarily based on self-reported questionnaires, and inclusion of additional objective physiological markers would improve mechanistic interpretation.

Conclusion

In this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 12 weeks of BME supplementation resulted in significant improvements in perceived stress, mood disturbance, anxiety symptoms, and both subjective and objective sleep parameters. Supplementation also produced a robust reduction in serum cortisol, supporting modulation of the HPA axis as a key mechanism underlying these effects. Improvements were evident early and increased progressively over the 84-day period. The findings are consistent with established adaptogenic and neuropsychological benefits of B. monnieri and suggest that the enhanced BME formulation may offer a safe, effective, and holistic approach for managing stress-related symptoms and improving sleep quality in otherwise healthy adults experiencing non-chronic stress. Further research is warranted to explore long-term effects, mechanistic pathways, and applications across broader populations.

Acknowledgements: We thank the participants of the study.

Funding: The study was supported by Samriddh Nutractive Private Limited (Hyderabad, India).

Author contributions: All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Conceptualization, methodology, Shashank Srinivas Gowda and Jestin V. Thomas; software, validation, formal analysis, data curation, visualization Jestin V. Thomas and Shashank Srinivas Gowda; investigation, supervision, resources, Shashank Srinivas Gowda; writing—original draft preparation, project administration Shashank Srinivas Gowda and Lincy Joshua; writing—review and editing, Jestin V. Thomas. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Disclosures: The entire study, including journal’s publication fee, was sponsored by Samriddh Nutractive Private Limited (Hyderabad, India).

Conflict of interest: None.

Compliance with ethics guidelines: A written approval was obtained from BGS Global Institute of Medical Sciences Institutional Ethics Committee, Bangalore, India, before commence of the study. The study was registered with the Clinical Trials Registry of India (CTRI/2025/05/087114). The study was conducted as per the regulatory requirements of the Indian Council of Medical Research, ethical guidelines, International Council for Harmonization Guidance on Good Clinical Practice (E6) and the Declaration of Helsinki. A voluntary informed consent was obtained, in written, from every participant before enrolling in the study.

Data Availability: The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- Selye H (1956) The Stress of Life. New York: McGraw Hill Books Co.

- Porth C (1998) Pathophysiology: Concepts of Altered Health States. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven.

- Gruner T (2006) Stress. J Comp Med 5:12-20.

- Sharma DK (2018) Physiology of stress and its management. J Med Stud Res 1:1.

- Kyrou I, Tsigos C (2008) Chronic stress, visceral obesity and gonadal dysfunction. Hormones 7:287-293.

- Shchaslyvyi AY, Antonenko SV, Telegeev GD (2024) Comprehensive review of chronic stress pathways and the efficacy of behavioral stress reduction programs (BSRPs) in managing diseases. Int J Environ Res Public Health 21:1077.

- Ghasemi F, Beversdorf DQ, Herman KC (2024) Stress and stress responses: A narrative literature review from physiological mechanisms to intervention approaches. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology 18:18344909241289222.

- Sinha R (2008) Chronic stress, drug use, and vulnerability to addiction. Ann NY Acad Sci 1141:105-130.

- Zhang J, Zhang WZ (2025) Stress-Induced Metabolic Disorders: Mechanisms, Pathologies, and Prospects. Am J Biomed Sci & Res 26:AJBSR.MS.ID.003506.

- Lehrer P (2007) Principles and Practice of Stress Management: Advances in the Field.

- Schwabe L, Dickinson A, Wolf OT (2011) Stress, habits, and drug addiction: a psychoneuroendocrinological perspective. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 19:53-63.

- Winston D, Maimes S (2007) Adaptogens: Herbs for Strength, Stamina, and Stress Relief. Rochester: Inner Traditions/Bear & Co.

- Aguiar S, Borowski T (2013) Neuropharmacological Review of the Nootropic Herb Bacopa monnieri. Rejuvenation Res 16:313-326.

- Chaudhari KS, Tiwari NR, Tiwari RR, Sharma RS (2017) Neurocognitive Effect of Nootropic Drug Brahmi (Bacopa monnieri) in Alzheimer’s Disease. Ann Neurosci 24:111-122.

- Russo A, Borrelli F (2005) Bacopa monniera, a reputed nootropic plant: an overview. Phytomedicine. 12:305-317.

- Kar A, Pandit S, Mukherjee K, Bahadur S, Mukherjee PK (2017) Safety assessment of selected medicinal food plants used in Ayurveda through CYP450 enzyme inhibition study. J Sci Food Agric 97:333-340.

- Kumar N, Abichandani LG, Thawani V, Gharpure KJ, Naidu MUR, et al. (2016) Efficacy of Standardized Extract of Bacopa monnieri (Bacognize®) on Cognitive Functions of Medical Students: A Six-Week, Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;4103423.

- Rai D, Bhatia G, Palit G, Pal R, Singh S, et al. (2003) Adaptogenic effect of Bacopa monniera (Brahmi). Pharmacol Biochem Behav 75:823-830.

- Sheikh N, Ahmad A, Siripurapu KB, Kuchibhotla VK, Singh S, et al. (2007) Effect of Bacopa monniera on stress induced changes in plasma corticosterone and brain monoamines in rats. J Ethnopharmacol 111:671-676.

- Sireeratawong S, Jaijoy K, Khonsung P, Lertprasertsuk N, Ingkaninan K (2016) Acute and chronic toxicities of Bacopa monnieri extract in Sprague-Dawley rats. BMC Complement Altern Med 16:249.

- Eraiah M, Shekhar HC, Lincy J, Thomas JV (2024) Effect of Bacopa monnieri extract on memory and cognitive skills in adult humans: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Psychiatry Cogn Behav 8:168.

- Downey LA, Kean J, Nemeh F, Lau A, Poll A, et al. (2013) An Acute, Double‐Blind, Placebo‐Controlled Crossover Study of 320 mg and 640 mg Doses of a Special Extract of Bacopa monnieri (CDRI 08) on Sustained Cognitive Performance. Phytother Res 27:1407-1413.

- Benson S, Downey LA, Stough C, Wetherell M, Zangara A, et al. (2014) An Acute, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Cross-over Study of 320 mg and 640 mg Doses of Bacopa monnieri (CDRI 08) on Multitasking Stress Reactivity and Mood. Phytother Res 28:551-559.

- Shetty SK, Rao PN, Shailaja U, Raj A, Suneetha KS, et al. (2021) The effect of Brahmi on depression, anxiety and stress during COVID-19. Eur J Integr Med 48:101898.

- Calabrese C, Gregory WL, Leo M, Kraemer D, Bone K, et al. (2008) Effects of a Standardized Bacopa monnieri Extract on Cognitive Performance, Anxiety, and Depression in the Elderly: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. J Altern Complement Med 14:707-713.

- Morgan A, Stevens J (2010) Does Bacopa monnieri Improve Memory Performance in Older Persons? Results of a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind Trial. J Altern Complement Med 16:753-759.

- Balkrishna A, Sharma N, Srivastava D, Kukreti A, Srivastava S, et al. (2024) Exploring the safety, efficacy, and bioactivity of herbal medicines: bridging traditional wisdom and modern science in healthcare. Future Integrative Medicine 3:35-49.

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R (1983) A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 24:385-396.

- Cohen S, Williamson G (1988) Perceived Stress in a Probability Sample of the United States. The Social Psychology of Health. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. 31-67.

- Harris KM, Gaffey AE, Schwartz JE, Krantz DS, Burg MM (2023) The Perceived Stress Scale as a Measure of Stress: Decomposing Score Variance in Longitudinal Behavioral Medicine Studies. Ann Behav Med 57:846-854.

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds III CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ (1989) The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 28:193-213.

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds III CF, Monk TH, Hoch CC, Yeager AL, et al. (1991) Quantification of subjective sleep quality in healthy elderly men and women using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). Sleep 14:331-338.

- McNair DM, Lorr M, Droppleman LF (1992) Profile of Mood States Manual. San Diego, CA: Education and Industrial Testing Service.

- Grove JR, Prapavessis H (1992) Preliminary evidence for the reliability and validity of an abbreviated Profile of Mood States. International Journal of Sport Psychology 23:93-109.

- Beck AT, Steer RA (1993) BAI: Beck Anxiety Inventory: Manual; Psychological Corp. Harcourt Brace: San Antonio, TX, USA.

- Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA (1988) An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol 56:893-897.

- Martin JL, Hakim AD (2011) Wrist actigraphy. Chest 139:1514-1527.

- Ancoli-Israel S, Cole R, Alessi C, Chambers M, Moorcroft W, et al. (2003) The role of actigraphy in the study of sleep and circadian rhythms. Sleep 26:342-392.

- Lee DY, Kim E, Choi MH (2015) Technical and clinical aspects of cortisol as a biochemical marker of chronic stress. BMB Rep 48:209-216.

- Oakley RH, Cidlowski JA (2013) The biology of the glucocorticoid receptor: new signaling mechanisms in health and disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol 132:1033-1044.

- Walker EA, Pellegrini MV (2023) Bacopa monnieri. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 [cited 2024 Jan 9].

- Stough C, Downey LA, Lloyd J, Silber B, Redman S, et al. (2008) Examining the nootropic effects of a special extract of Bacopa monniera on human cognitive functioning: 90 day double‐blind placebo‐controlled randomized trial. Phytother Res 22:1629-1634.

- Raghav S, Singh H, Dalal PK, Srivastava JS, Asthana OP (2006) Randomized controlled trial of standardized Bacopa monniera extract in age-associated memory impairment. Indian J Psychiatry 48:238-242.

- Pase MP, Kean J, Sarris J, Neale C, Scholey AB, et al. (2012) The Cognitive-Enhancing Effects of Bacopa monnieri : A Systematic Review of Randomized, Controlled Human Clinical Trials. J Altern Complement Med 18:647–652.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.