Early Intervention Strategies for Supporting Language Development in English Language Learners with Diverse Needs

by Jordan Ohlrich*

Graduate Student & Preschool Educator, University of Nebraska Omaha University of Nebraska Omaha, USA

*Corresponding author: Jordan Ohlrich, Graduate Student & Preschool Educator, University of Nebraska Omaha University of Nebraska Omaha, USA

Received Date: 14 July 2025

Accepted Date: 22 July 2025

Published Date: 24 July 2025

Citation: Ohlrich J. (2025). Early Intervention Strategies for Supporting Language Development in English Language Learners with Diverse Needs. Educ Res Appl 10: 244. https://doi.org/10.29011/2575-7032.100244

Abstract

This action research study examined the need for effective early intervention strategies to support vocabulary development in English Language Learners (ELLs) with diverse needs in a preschool setting. Many ELL students, particularly those with disabilities, struggle to acquire and apply new vocabulary without targeted support. To address this, two instructional methods were implemented: the structured language routine Question, Signal, Stem, Share, Assess (QSSSA) and the use of visual support. Over the course of seven weeks, two students were observed using pre- and post-assessments, daily observations, and teacher reflections. Results showed a clear positive impact on both students' vocabulary acquisition and their confidence in using language during instructional activities. These findings highlight the importance of intentional, multimodal strategies, such as QSSSA, in promoting vocabulary development among dual-identified learners in early childhood education.

Introduction

In a preschool classroom within a large urban district in the Midwest, the needs of English Language Learners (ELL) with disabilities often intersect in complex ways. Many of these young children arrive with limited exposure to English and simultaneously require special education services to support developmental delays. As an inclusive preschool teacher, I have observed a recurring challenge: ELL students with disabilities frequently struggle to acquire and use age-appropriate vocabulary, even when immersed in language-rich environments. This issue impacts their ability to engage with peers, follow directions, and participate meaningfully in early learning activities. The intersection of language learning and a developmental delay presents unique instructional demands that require both targeted strategies and timely intervention [1].

Research indicates that without early and intentional language support, English Language Learners in special education may experience long-term academic setbacks [1]. This issue is particularly concerning within early childhood settings, where language development forms the foundation for future learning. Despite federal mandates emphasizing early intervention and inclusive practices [2] many educators lack clear guidance on how to adapt instruction to meet the dual needs of these learners. While general strategies such as relying on repetition or simplified language to support English Language Learners or providing one-on-one adult support for students with disabilities exist to address each group separately, few resources consider the combined needs of students who fall into both categories. This study aims to fill that gap by examining the effectiveness of targeted, evidence-based language interventions, such as the QSSSA routine and visual supports like picture cards and real-life images, for preschool English Language Learners with disabilities.

Statement of the Problem

Young English Language Learners with disabilities often demonstrate limited vocabulary development compared to their peers, which can significantly impact their ability to participate in classroom activities. In my classroom, this challenge is especially evident when students struggle to follow directions, express basic needs, or engage in conversations with peers and adults. One of my students, a four-year-old boy, is currently in the Student Assistance Team (SAT) process, a school-based support system used to identify and monitor students who may need special education services. He is being considered for speech-language support due to ongoing difficulties with expressive language. He often pauses mid-sentence or substitutes incorrect words, making it difficult to communicate clearly. Another student, a five-year-old boy with an Individualized Education Program (IEP) for a developmental delay, also shows significant challenges with vocabulary. He typically responds with one-word answers and struggles to use newly introduced vocabulary in context. There is also suspected trauma at home, which may be affecting his language and overall development. When planning how best to support each student, we as a team consider all factors, including language, disability, and home environment. These examples highlight the complexity of working with dual-identified learners and reinforce the need for intentional, responsive teaching strategies.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this action research project is to examine the impact of using two specific strategies, Question, Signal, Stem, Share, Assess (QSSSA) and visual supports, on vocabulary acquisition in two preschool-aged English Language Learners, one with an IEP for speech and behavior services and one who is currently referred to undergo evaluation for a suspected developmental delay. By implementing these strategies during small-group sessions, I aimed to improve students’ ability to speak comfortably with their peers while using common vocabulary. The inquiry is deeply personal, rooted in my observations of inequities and communication abilities in the classroom. I believe that refining instructional approaches for dual-identified learners will not only benefit the targeted students but will also inform best practices across early childhood settings.

Research Question

The central research question guiding this study was: What is the impact of the routine of QSSSA (Question, Signal, Stem, Share, Assess), and visuals on vocabulary acquisition in preschool-aged English Language Learners with and without disabilities? By exploring this question in the context of my classroom, I aimed to find practical strategies to support language growth and make early learning more accessible and meaningful for both students. Through this work, I hope to see increased student engagement, improved communication, and more confident participation in classroom routines. More broadly, I want my students to be academically prepared because early childhood lays the foundation for future success.

Literature Review

Early intervention strategies for English Language Learners with disabilities are essential to promoting equitable access to language development opportunities, as these students face the dual challenge of acquiring a new language while also navigating developmental delays. These students face the dual challenge of acquiring a new language while also navigating developmental or learning differences, often resulting in academic, social, and behavioral challenges. This literature review synthesizes current research across five key themes: challenges facing English Language Learners with disabilities, the significance of early intervention, evidence-based instructional strategies, family engagement, and educator preparation. Foundational theoretical frameworks also inform the direction and design of this study.

Theoretical Frameworks

This research is grounded in Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory, which emphasizes the importance of language and social interaction in cognitive development [3]. Central to this theory is the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), which highlights the value of scaffolding through peer modeling and guided dialogue. Scaffolding refers to the support and guidance provided by a teacher or more knowledgeable peer that helps a learner accomplish tasks they cannot yet do independently. As the learner’s skills improve, this support is gradually withdrawn, promoting increasing independence and mastery. In addition, the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework promotes inclusive education by encouraging flexible approaches to representation, engagement, and expression [4]. These approaches support the use of strategies like QSSSA and visual aids to create accessible, developmentally appropriate learning experiences for diverse learners.

Challenges Facing ELLs with Disabilities

ELL students are one of the fastest-growing student populations in U.S. schools, and many are disproportionately represented in special education. [1] report that nearly half of English Language Learners receiving special education services are diagnosed with learning disabilities, compared to just over a third of their non-ELL peers. This disparity points to potential misidentification and a lack of culturally responsive practices. Traci De Land, a Speech Language Pathologist (SLP), notes that English Language Learners (ELL) with disabilities often struggle with routine tasks like following directions and participating in group activities, which may lead to withdrawal and delays in both language and social-emotional development. These realities emphasize the need for early, targeted support.

The Role and Impact of Early Intervention

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (n.d.), early intervention provides services and support for young children with developmental delays aimed at improving long-term outcomes. Speech-Language Pathologists (SLPs) play a vital role in early intervention by using play-based observations and naturalistic settings to assess communication skills and promote language development. This approach creates meaningful, individualized learning opportunities during the critical early years. Traci Deland, Speech-Language Pathologist at Omaha Public Schools, explains, “Early intervention is crucial for supporting language development in young learners, especially those facing additional challenges. Involving families in the process ensures that support continues beyond the classroom, creating a stronger foundation for academic and social success.”

Evidence-Based Instructional Strategies

A range of evidence-based strategies has been shown to support language development in English Language Leaners with disabilities. [5] Emphasize the value of “rich conversations” that build vocabulary, sentence structure, and communication skills. QSSSA and visual supports work well together to support this goal. QSSSA encourages structured peer interaction through questions and sentence stems, while visual supports reinforce key vocabulary and meaning. Combined, they offer accessible, engaging instruction that supports both comprehension and expression for diverse learners.

QSSSA: Structured Language Interaction

QSSSA (Question, Signal, Stem, Share, and Assess) is a classroom discussion strategy designed to support language learners by providing structured opportunities to speak. This method reduces cognitive load and anxiety by offering sentence frames, signals for participation, and built-in opportunities for peer interaction. [6] Highlights QSSSA as a flexible tool that scaffolds student responses while promoting engagement and oral language development. When consistently used, QSSSA helps students grow more confident in speaking and interacting during group activities.

Visual Supports: Multimodal Learning Tools

Visual strategies are widely used to help young learners make connections between language and meaning. Tools such as picture schedules, labeled images, and short video clips can reinforce vocabulary and support routine understanding. Research [7, 8] shows that multimodal environments those combining visual, auditory, and hands-on elements enhance vocabulary retention and reduce confusion. However, overdependence on visuals can limit opportunities for students to practice language independently. For this reason, visuals should be used as a foundation, gradually fading as students become communicators that are more confident.

Culturally Responsive Teaching

Culturally responsive teaching (CRT) also plays a vital role in inclusive classrooms. Bennett et al. (2018) argue that when teachers reflect on their own cultural biases and intentionally incorporate students’ identities into daily instruction, they foster more engaging and affirming learning environments. This practice is especially critical when working with English Language Learners, whose language development is influenced by both their cultural backgrounds and classroom experiences.

Conclusion

This review highlights the importance of early, inclusive, and intentional strategies for supporting ELL with disabilities. Grounded in sociocultural theory and the UDL framework, tools like QSSSA and visual support are most effective when delivered by well-trained educators in collaboration with families. These insights directly shaped the design of this study, which explores how QSSSA and visual supports impact vocabulary development in preschool ELLs with diverse needs. The following section outlines the methodology used to implement and evaluate these strategies in a real classroom context.

Methodology

This action research study examined the impact of using QSSSA (Question, Signal, Stem, Share, and Assess) and visual supports to improve vocabulary acquisition in two preschool-aged English Language Learners with diverse abilities. The study took place in a preschool classroom located within an elementary school serving a multilingual population, including children receiving Head Start and early intervention services. Action research was selected to allow for direct instructional changes in response to student needs. A mixed-methods design was used to gather both numerical data and qualitative observations to measure the effectiveness of the intervention.

Participants and Setting

Two preschool students participated in the study. Student 1 is an English Language Learner, as well as receives special education services for speech and behavior. Student 2 is also an English Language Learner (ELL) and was in the Student Assistance Team (SAT) process to determine the need for services. Both students were selected because they demonstrated a need for language development support. This need was evident through limited verbal responses during group activities, difficulty following directions, and minimal use of academic vocabulary during classroom interactions. Informal observations and assessment data further highlighted delays in expressive and receptive language skills, confirming the need for targeted intervention.

The study was carried out in their regular classroom, where I served as both the teacher and the researcher. I collected and analyzed the data while remaining aware of my role in influencing instruction and outcomes. The intervention lasted seven weeks, with instructional sessions taking place three times per week for about 15 minutes. Instruction was centered around the QSSSA strategy, paired with visual supports including picture cues, gestures, and sentence frames. Vocabulary was introduced during group lessons and practiced through structured activities and conversations. Lessons were designed to be interactive and responsive to students' needs.

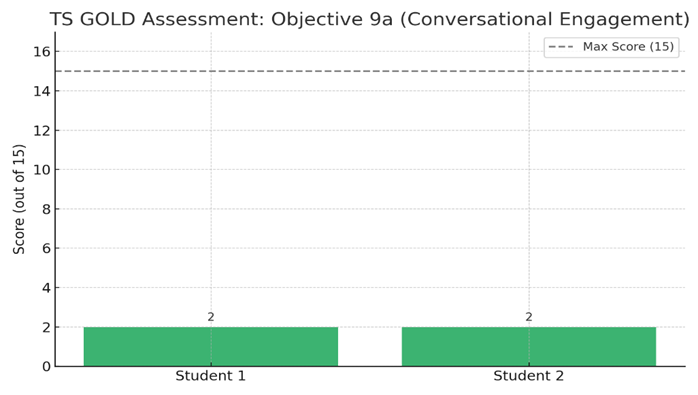

Teaching Strategies (TS) GOLD Assessment Data

Teaching Strategies (TS) GOLD language assessment scores were used to help select the two student participants for this study. This tool provides a developmental progression of language skills, including listening, understanding, and speaking. Specifically, Objective 9a, which measures conversational engagement, is aligned closely with the objectives of the intervention. Both Student 1 and Student 2 scored 2 out of 15 on this objective, indicating minimal engagement in back-and-forth conversations. These notably low scores, combined with daily classroom observations, highlighted a need for targeted language support and helped identify students who would most benefit from intervention. The graph below shows each student's score on this objective. This data confirmed that structured strategies like QSSSA and visual support were necessary to build foundational language skills and promote meaningful participation (Figure 1).

Figure 1: TS Gold Assessment Data.

Data Collection and Analysis

Qualitative Data

Qualitative insights were gathered through weekly anecdotal notes I recorded, documenting classroom interactions, vocabulary use, and student behavior. These notes were analyzed for recurring patterns in participation and engagement. Observational data played a key role in informing real-time instructional decisions, allowing for responsive adjustments to better meet individual needs.

During QSSSA activities, I used structured prompts like "How are you feeling today?", "Are you happy or sad today?", "Where do we sit at the table?", and "What is your favorite fruit?" Each question was paired with visuals that matched both the vocabulary words and the expected answers, supporting comprehension and participation. Students used sentence stems such as "I feel------ because..." or "My favorite fruit is -------" to build complete responses and practice expressive language. These visuals were essential in helping students connect words to meaning and respond with confidence. In total, 14 vocabulary words were introduced over the seven-week intervention 10 core words at the start, followed by 4 additional words once students showed readiness.

Quantitative Data

Quantitative data was collected through multiple sources to capture measurable student outcomes. These included pre- and post-vocabulary assessments, and a Google Sheet used to track student responses. Quantitative data from the vocabulary assessments were compared to monitor growth over the seven-week intervention. In addition, a yearly assessment using TS GOLD was reviewed, specifically examining each student’s scores on language objectives that measure expressive and receptive communication skills. These tools offered both immediate insights and long-term developmental benchmarks.

Ethical Consideration

This study was reviewed and approved by Omaha Public Schools (OPS) according to district guidelines for conducting research in educational settings. All research activities followed ethical standards, including obtaining administrative approval, protecting student confidentiality, and ensuring that participation did not disrupt instructional time or student services.

Data Triangulated

To strengthen the validity of the findings, this study used data triangulation by integrating both qualitative and quantitative sources. Quantitative data from vocabulary assessments and TS GOLD scores provided measurable evidence of language growth, while qualitative data from anecdotal notes and classroom observations captured the context behind that progress, such as engagement levels, use of targeted vocabulary, and student confidence. Together, these data sets offered a more complete and nuanced understanding of each student’s development. This layered approach allowed for cross-verification of results, ensuring that patterns observed in one area were supported by evidence in another, ultimately enhancing the reliability and depth of the conclusions drawn.

Limitations

While the study yielded positive results, it is important to acknowledge limitations. The small sample size and brief intervention period limit the ability to generalize findings to a larger population. Still, the growth observed in both students suggests that this approach is effective and worth exploring further. Future research could build upon this study by including a larger and more diverse sample of students to enhance generalizability, examining the effectiveness of interventions across varied classroom settings such as inclusive, dual-language, or self-contained environments, and assessing long-term language development outcomes over the course of an entire academic year. This would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the sustained impact of early intervention strategies on vocabulary acquisition and language growth in English Language Learners with diverse needs.

Findings

Both Student 1 and Student 2 demonstrated growth in vocabulary acquisition and overall language confidence because of the intervention. Pre and post-assessments showed measurable improvements in their understanding and use of targeted vocabulary. In classroom settings, both students became more engaged and increasingly willing to participate in group conversations and language-based activities. Vocabulary assessment data supported this growth; with both students showing an increase in correctly identified and used words from the beginning to the end of the study. These gains were reinforced by daily teacher observations and tracking. Initially, the students relied heavily on visual prompts to engage with vocabulary, but by the end of the seven-week intervention, they were responding more independently, indicating stronger confidence and retention of new language.

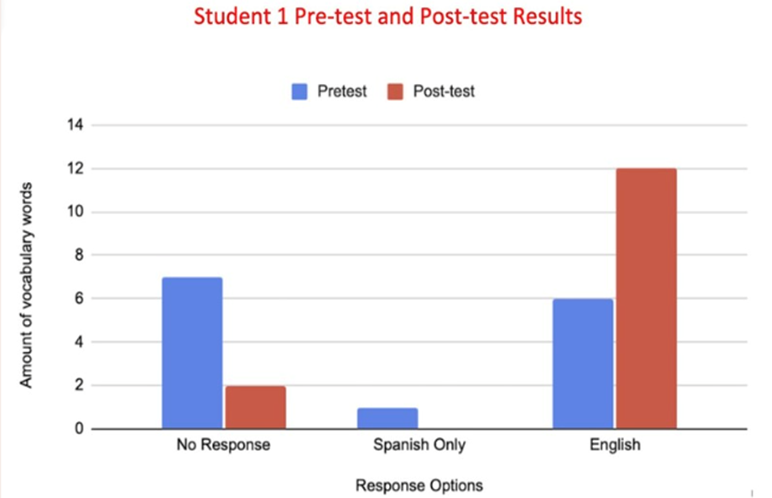

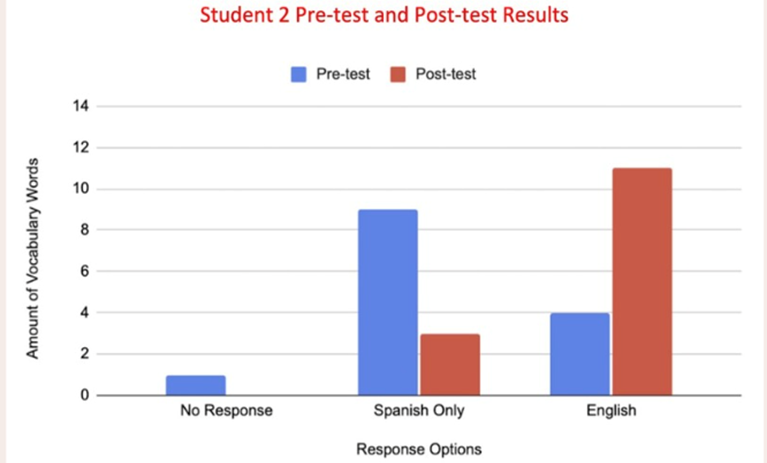

Pre- and Post-Test Data

The graphs below display changes in vocabulary use between the pre-test and post-test for Student 1 and Student 2, focusing on three response types: No Response, Spanish Only, and English. At the beginning of the study, both students demonstrated limited use of English vocabulary. Student 1 frequently gave no response and produced only a few English words, while Student 2 responded mostly in Spanish (Figures 2, 3).

By the end of the intervention, both students showed a significant increase in the number of English words spoken. Student 1 demonstrated 13 English responses on the post-test, and Student 2 increased to 11. In this context, "correct" responses were defined as vocabulary words spoken in English. However, we were proud of every attempt made by both students. Whether the responses were in Spanish or partially correct, each one reflected growing confidence, engagement, and a willingness to communicate. These results underscore the importance of creating a supportive language environment where all efforts are acknowledged as meaningful progress.

Figures 2 and 3: Pre- and Post-Test Results.

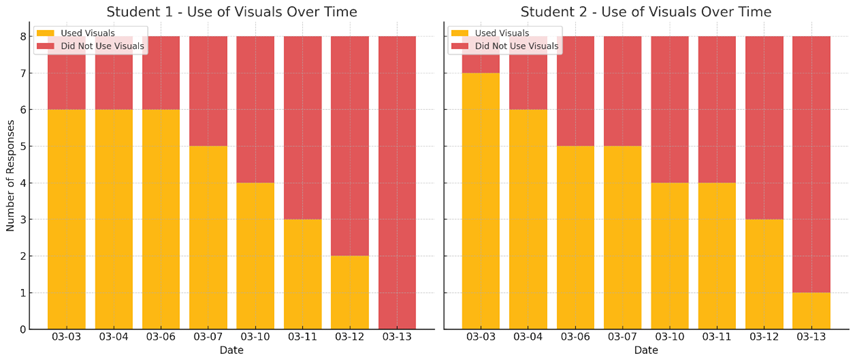

QSSSA Results

The following graphs illustrate how each student used visual supports during QSSSA activities across several dates in March 2025. A core component of this study was integrating visuals with structured language routines to support vocabulary development in English Language Learners (ELL) with diverse needs. Early in the intervention, both students relied heavily on visual cues such as picture cards and gestures to access and express newly introduced vocabulary. Prompts like “How are you feeling today?” or “What do we sit on at the table?” were paired with simple sentence stems and visuals to scaffold student responses.

Student 1 used visuals for 6 of 8 responses on the first three days. By the final session on March 13, he responded independently without visuals in all 8 recorded instances. Student 2 began with even higher reliance, using visuals for 7 of 8 responses on March 3. Over time, his need for support decreased, and by the last session, only 1 of his 8 responses required a visual prompt.

This steady decrease in visual reliance reflects one of the central goals of the study: to move students from supported participation to independent language use. As vocabulary became more familiar, both students began initiating responses more confidently and with greater fluency. These patterns demonstrate how pairing QSSSA with intentional visual supports can successfully scaffold language development, and then fade supports as students internalize new vocabulary (Figure 4).

Figure 4: QSSSA Assessment Results

Anecdotal Notes

Anecdotal notes revealed key behavioral trends related to language growth during intervention sessions. Student 1 became more confident, frequently responding to questions without prompting and initiating conversations with peers. For example, during a morning check-in, they independently used the word happy to describe how they were feeling and later used sad on a different day, showing an increased ability to express their emotions based on their mood. Student 2 showed steady progress when vocabulary was embedded across multiple activities and reinforced through consistent routines. One morning, during a small group, Student 2 correctly used the word chair when asked where they were sitting. A word collage was created to highlight the most common themes noted during these sessions-words like growth, engagement, confidence, support, participation, repetition, independence, and visuals-capturing the patterns that emerged throughout the intervention. These examples show that both students were not only learning new words but also using them more independently and meaningfully during different times of the day.

While not formally measured, both students demonstrated an increase in peer interaction. As their vocabulary and language confidence developed, they participated more frequently in shared activities and began initiating conversations during free play and recess. This social growth, though unexpected, was a meaningful outcome of the intervention and demonstrated the broader impact of targeted language support. Figure 5 displays all the most common words found in my notes, with prominent terms like confidence, engagement, and participation highlighting how language development also fostered greater social inclusion, emotional expression, and independent communication among the students.

Figure 5: Anecdotal Notes Results.

Summary of Findings

This study showed that using QSSSA and visual supports together helped both students build vocabulary and become more confident language users. Pre- and post-test data showed clear progress: Student 1 went from giving no response to saying 13 English words, and Student 2 increased from mostly Spanish responses to 11 English words. While not every answer was fully accurate, each attempt showed growth in engagement and a willingness to communicate.

The QSSSA graph highlights how visuals supported students early on. At first, both students relied heavily on picture cards and sentence stems to participate. They were just beginning to respond and often changed or repeated their answers. Over time, they grew more confident and needed less support. By the final sessions, they were answering more independently and using the targeted vocabulary in familiar routines.

Anecdotal notes supported the data. Student 1 began speaking without prompting, and Student 2 responded more consistently when vocabulary was reinforced. Both showed increased peer interaction during play, linking language growth to social engagement. The final word collage highlights key themes confidence, communication, and participation. Despite the small sample size, improvements across visuals, assessments, and observations suggest QSSSA with visuals effectively supports language development in preschoolers. These findings point to broader applications in inclusive early childhood settings.

Discussion and Implications

This action research study investigated how QSSSA (Question, Signal, Stem, Share, Assess) and visual supports impacted vocabulary acquisition in preschool-aged English Language Learners (ELL) with diverse abilities. Results showed clear growth in vocabulary understanding and use, with both students demonstrating increased engagement and independence during language-based activities. These findings align with previous research on scaffolded instruction and multimodal supports, highlighting how structured strategies can foster expressive language and student confidence [5, 8].

Benefits for Students & Implications for Practice

Through this intervention, both students showed measurable growth. Student 1 increased correct vocabulary usage from 3 out of 10 words on the pre-assessment to 8 out of 10 on the post-assessment. Student 2 improved from 2 to 7. At the start, both students relied heavily on visual prompts such as labeled picture cards and real-life photo supports. For example, Student 1 needed to see a picture of a chair to say the word correctly, but by the intervention’s end, they independently said, “I sit in a chair” without any prompts. They responded using complete sentences and sentence stems like “I sit in a” or “I am feeling.” This growth reflects Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory and the Zone of Proximal Development, which emphasizes the value of guided support in moving students toward independent learning. The intervention also supported social-emotional development, with both students initiating more peer conversations during group activities and playtime, which had not been observed before the study.

These outcomes suggest that QSSSA, when paired with intentional visual supports, can serve as a powerful and practical strategy for promoting language development in multilingual learners. For educators, incorporating structured routines like QSSSA with simplified sentence stems, familiar visuals, and time for peer dialogue can support vocabulary growth, confidence, and classroom participation. These strategies are easy to embed into daily instruction, require minimal preparation, and can be adapted for a range of developmental levels. As classrooms continue to become more linguistically and developmentally diverse, inclusive and scaffolded instruction becomes essential to meeting student needs and supporting meaningful growth.

Connection to Literature

This study highlighted the importance of planning purposeful, language-rich opportunities for English Language Learners (ELL), particularly in inclusive preschool classrooms where students may receive early intervention or special education services. [3] sociocultural theory and the Universal Design for Learning, strategies like QSSSA and visual supports allow educators to scaffold language development in developmentally appropriate, flexible ways. As discussed by Houen [5], extended conversational interactions, what they call “rich talk”, support vocabulary growth and expressive language. In this study, QSSSA was adapted using simplified sentence stems, paired visuals, and helping students feel confident while speaking. Similarly, visual tools were intentionally selected based on classroom relevance and gradually faded to support independent communication, aligning with the findings of Rosmiati [8].

More broadly, this action research contributes to the field by offering practical, low-cost strategies to support multilingual learners in early childhood an increasingly diverse and underserved group [1]. As the literature suggests, early culturally responsive teaching can prevent long-term academic and social-emotional challenges [9]. My study honored students’ diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds by using visual supports and language routines tailored to English Language Learners. The intervention-built vocabulary while increasing confidence and a sense of belonging, making learning more relevant and accessible for all students. Ultimately, these findings not only benefited the children involved but also reshaped the teacher-researcher’s practice, deepening an understanding of how responsive, research-based instruction can drive meaningful growth in student vocabulary, confidence, and participation.

Growth as a Teacher

Reflecting on the research process, this study reinforced the importance of being a responsive, reflective practitioner. The action research model allowed for immediate instructional changes based on student needs and real-time observations, which made teaching more dynamic and personalized. As I implemented and adjusted strategies like QSSSA and visual supports, I became more aware of how small shifts in instruction can present meaningful growth. This experience also challenged me to think critically about the intersection of language development, disability, and equity in early childhood education.

Implications for Future Research

Future research could examine how QSSSA and visual supports impact a broader and more diverse group of students across various settings. While this study focused on two preschool-aged English Language Learners over seven weeks, increasing the sample size and duration would provide deeper insight into long-term impacts. It would also be valuable to explore how family involvement, home-language connections, and co-teaching environments influence the success of these strategies. Importantly, QSSSA is highly adaptable and can be studied across different grade levels, content areas, and times of day from morning meetings to math instruction. Teachers can modify the approach by adjusting the visuals, sentence stems, or discussion topics based on student needs and subject matter. For educators implementing this strategy, beginning with familiar visuals and providing repeated practice opportunities can support both language development and student confidence. With thoughtful planning, QSSSA can become a flexible, inclusive tool that supports diverse learners in any classroom.

Conclusion

This study aims to explore how intentional, scaffolded strategies can assist ELLs with diverse abilities in confidently acquiring and using new vocabulary in the classroom. Grounded in Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory and Universal Design for Learning, the research highlights how language develops through social interaction, guided support, and flexible, inclusive teaching methods. The results show that with consistent, developmentally appropriate supports such as QSSSA and visuals, students can not only improve their language skills but also enhance their confidence and participation. These findings align with the broader literature emphasizing the significance of early intervention, rich language environments [5], and multimodal supports [8-11] for English Language Learners (ELL) with a disability.

Every child deserves the opportunity to build a strong foundation in language, especially during the early years when vocabulary development is crucial for later academic success [5]. Educators who adopt culturally responsive, evidence-based practices help close opportunity gaps and create learning spaces where all students can thrive [1]. This research highlights how strategies like QSSSA and visual supports can be successfully implemented in early childhood classrooms to support inclusive and intentional instruction. When used consistently, these tools promote equitable language development and responsive teaching tailored to diverse learner needs.

References

- Wei Y, Hovey KA, Gerzel SL, Hsiao Y, Miller R.D. (2023). Culturally responsive and high‐leverage practices: Facilitating effective instruction for English learners with learning disabilities. TESOL Journal, 14: 1-15.

- National Center for Learning Disabilities. (2006). A parent's guide to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. ERIC.

- Vygotsky LS. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press. Retrieved in Online.

- CAST. (n.d.). Universal Design for Learning. Retrieved in Online.

- Houen S, Thorpe K, van Os D, Westwood E, Toon D. (2022). Eliciting and responding to young children's talk: A systematic review of educators' interactional strategies that promote rich conversations with children aged 2-5 years. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 59: 25-41.

- Seidlitz Education. (2019). QSSSA: More than turn & talk. Retrieved in Online.

- Boutot A. (2017). Autism Spectrum Disorder: A handbook for parents and professionals (2nd ed.). Pearson.

- Rosmiati A, Kurniawan RA, Prilosadoso BH, Panindias AN. (2020). Aspects of visual communication design in animated learning media for early childhood and kindergarten. International Journal of Social Sciences, 3: 122-126.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.) (2024). Learn the signs. Act early. Retrieved from Online.

- Goldman SE, Burke MM. (2017). The effectiveness of interventions to increase parent involvement in special education: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Exceptionality. 25: 97-115.

- University of Washington. (n.d.). What is an Individualized Education Plan (IEP)? DO-IT.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.