Diverse Triggers of Macrophage Activation Syndrome

by Juliette Hafner1,2*, Bianca Gautron Moura2, Gaëlle Rhyner Agocs2, Filipe Martins2, Alessandra Curioni-Fontecedro2,3, Danny Kupka2

1Department of Internal Medicine, HFR Fribourg Hospitals, Fribourg, Switzerland

2Department of Oncology, HFR Fribourg Hospitals, Fribourg, Switzerland

3Faculty of science and Medicine, University of Fribourg, Fribourg, Switzerland

*Corresponding author: Juliette Hafner, Department of Internal Medicine, HFR Fribourg Hospitals, Fribourg, Switzerland

Received Date: 02 December 2024

Accepted Date: 06 December 2024

Published Date: 09 December 2024

Citation: Hafner J, Kupka D, Moura BG, Agocs GR, Martins F, et al (2024) Diverse Triggers of Macrophage Activation Syndrome. Ann Case Report. 9: 2105. https://doi.org/10.29011/2574-7754.102105

Abstract

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) represents a critical, potentially fatal condition marked by disproportionate activity within both the innate and adaptive immune systems. Predominantly observed in oncological contexts, HLH has seen a rising incidence over recent years. Here, we present two cases that underscore the different origins of secondary HLH in cancer patients: one triggered by immune checkpoint inhibitors and another by Hodgkin’s lymphoma. These instances illustrate the complexity of the diagnosis and management of HLH, especially if resulting as a consequence of immunotherapy. Moreover, each case sheds light on the intricate interaction between therapeutic agents and the immune system’s regulatory capacity, offering insights into the spectrum of HLH etiologies and emphasizing the need for prompt monitoring and management.

List of Abbreviations: ABVD: Doxorubicin, Bleomycin, Vinblastine and Dacarbazine; CMV: Cytomegalovirus; CRP: C-reaction protein; CRS - Cytokine released syndrome; DD: Differential Diagnosis; DIC: Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation; EBV: Epstein-Barr Virus; HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus; HLH: Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis syndrome; HScore: Hemophagocytic syndrome Score; HSV: Herpes simplex virus; ICIs: Immune checkpoint inhibitors; IFNγ: Interferon γ; IL: Interleukine; IPS: International Pronostic Score; MAS: Macrophage Activation Syndrome; OS: Overall survival; PY - Pack year; spp: species; TNFα: Tumor Necrosis Factor α.

Keywords: Macrophage Activation Syndrome; Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis; Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors; Hodgkin Syndrome; Hematology; Oncology.

Introduction

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) represents an uncontrolled inflammatory syndrome clinically characterized by fever, reduced blood counts, and hyperferritinemia. A triad prompting the initiation of complementary investigations and fast intervention due to its rapid evolution towards multiorgan failure if left untreated (Cox et al. Lancet Rheumatol., 2024), immune dysregulation, typified by hyperferritinemia and the overactivation of T lymphocytes and macrophages, culminating in a cytokine storm. The North American Consortium for Histiocytosis (NACHO) reframes HLH, distinguishing ‘HLH Disease’ from ‘HLH Disease mimics’, the former attributable to innate or acquired immunodeficiency and the latter unrelated to immunosuppression. Rheumatological HLH, or macrophage activation syndrome (MAS-HLH), bears the standard nomenclature in English-speaking regions, and we adopt herewith ‘secondary HLH’ for the following patient cases. Secondary HLH is a life-threatening complication of various etiology. In order of frequency, hematological malignancies constitute nearly a third of HLH causes, followed by infectious and rheumatological diseases, with primary HLH representing <5% of cases [1]. Hepatomegaly and splenomegaly accompany the abovementioned clinical- biological triad in nearly two-third of cases as consequence of increased T cell and macrophage proliferation, frequently associated with disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) [2-5].

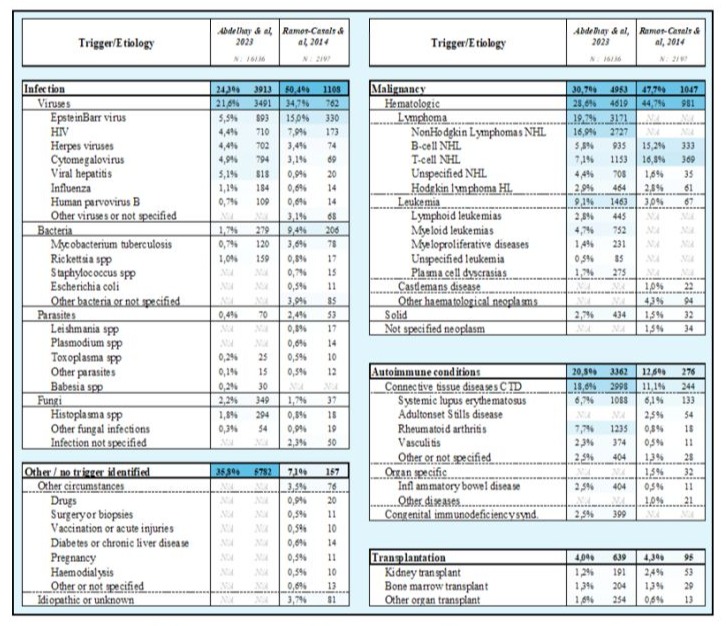

Central to HLH pathophysiology are immune cells CD8+ and NK T lymphocytes, and macrophages which orchestrate wound healing, host defense, and immune regulation in the physiological setting. In healthy conditions, cytotoxic T-cells and macrophages mediate target cell destruction through perforin/granzyme release for the first and phagocytosis for the second cell subtype. In HLH, however, a failure in this cytotoxic function, through genetic mutations (primary HLH) or immune dysregulation (secondary HLH), leads to rapid cytokine release and ineffective cell lysis. Primary HLH typically manifests in infancy, necessitating etoposide+/- ciclosporin A (following HLH-94 or –2004 protocols) followed by allogeneic stem cell transplantation, while secondary HLH can arise at any age due to cancer, infection, autoimmune condition, but also without an identifiable trigger (idiopathic HLH) [6]. Laboratory findings encompass worsening pancytopenia, accompanied by anti-inflammatory syndrome indicated by hyperferritinemia and hypertriglyceridemia because of macrophage hyperactivation and an acute phase reaction. The diagnosis, lacking a gold standard, follows the HLH-2004 criteria or the HS Score (i.e. HScore), which estimates the likelihood based on biological markers. The HScore allows earlier diagnostic recognition compared to HLH-2004 criteria and should be repeated over time in parallel to clinical and biological evolution of suspected cases. Ferritin levels above 10’000 ug/L were shown to have a high sensitivity and specificity (≥ 90%) for HLH diagnosis in a retrospective study [7]. Though hemophagocytosis on bone marrow examination is routine, it’s neither definitive nor exclusive to HLH given its appearance in non-HLH intensive care patients [8-11]. HLH treatment relies on causative treatment such as chemotherapy in the case of associated malignancy, often accompanied by T-cell directed immunosuppressive therapy including etoposide, glucocorticoids, ciclosporin A, antithymocyte serum, JAK-STAT inhibitors, and immunomodulatory therapy including intravenous immunoglobulins in case of severe/ refractory HLH, rheumatological-HLH, and HLH caused by innate (primary HLH) or acquired immunodeficiency. Cytokine blockade targeting TNFa, IL-1, IL-6R, IL-18 can be discussed as it has proven activity in cases of primary HLH, and as part of causative treatment in the case of rheumatological-HLH. HLH related to EBV reactivation should be treated with anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies [12]. Prognosis varies, being most dire for HLH secondary to hematological malignancies, followed by autoimmune, viral, and idiopathic forms [13,14] (Table 1).

Here we present two cases that elucidate the divergent etiologies of secondary HLH in the oncological setting: one driven by immunotherapy-induced immune dysregulation and the other caused by Hodgkin’s lymphoma. These cases exemplify the complexity of HLH diagnosis and management, underscoring the heterogeneity of its pathogenesis where therapeutic interventions such as immunotherapy can inadvertently trigger HLH, and malignancies like Hodgkin’s lymphoma can lead to an aberrant immune response manifesting as HLH. Each case serves to display the intricate interplay between therapeutic modalities and the immune system’s capacity for dysregulation, contributing valuable insights into the spectrum of HLH etiologies.

Case Presentation

Case 1 - 71-year-old Caucasian patient with a relapse of malignant cutaneous melanoma.

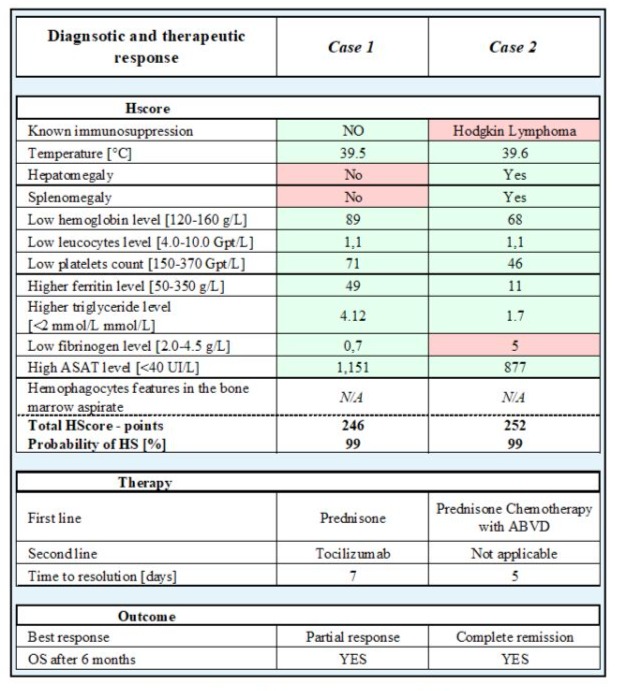

The first case is a 71-year-old Caucasian patient with a relapse of malignant cutaneous melanoma, initially Breslow 2.7 mm, pT3a pN0 (0/1) cM0, stage IIA according to AJCC 8th edition, excised 5 years before the relapse and known to be an active smoker at 45 PY. At relapse, the patient was diagnosed with gastric metastasis of the BRAF- and MEK-negative mutations melanoma that had also metastasized to the liver and lymph nodes. Checkpoint inhibitors with anti-CTLA4 (ipilimumab) and anti-PD1 (nivolumab) was started, along with five sessions of radiotherapy to the stomach. One week after the 2nd cycle of immunotherapy, the patient consulted the emergency department because of a drop in general condition and a fever since the previous day, with no other complaints. On clinical examination, the patient had fever at 38.8°C, tachypnea and oxygen saturation at 90%. Laboratory findings showed a mild inflammatory syndrome with no leukocytosis, anemia at 105g/L, thrombocytes within the limit at 150 G/L with no sign of hemolysis. He rapidly developed acute liver and kidney failure, which necessitated his transfer to intensive care. D-dimer were at 13,000ng/ml (normal range < 500ng/ml) and PTT was prolonged. Initially, a urinary tract infection and autoimmune hepatitis were suspected. Treatment with antibiotics and methylprednisolone 250mg IV was started. The patient’s general condition rapidly deteriorated, with persistent fever, hypoxemia and respiratory distress, however hemodynamically stable. Laboratory findings showed a massive increase in liver enzymes, a slight increase in bilirubin, together with increased ferritin > 25,000 µg/L, hypertriglyceridemia, a massively increased (334pg/ml) IL6 and CRP, progressive pancytopenia with thrombocytopenia and leukopenia, with stable hemoglobin, low fibrinogen and D-dimers > 35’00 ng/ml. In this context, a differential diagnosis of macrophage activation syndrome was suspected as well as a cytokine release syndrome (CRS). At that moment, the HS score was 246 points, implying a 99% chance of HLH. At the same time, the patient also fulfilled the biological criteria for DIC. In this context, the treatment was modified: the patient received tocilizumab (8mg/ kg), followed by a maintenance of methylprednisolone 250mg IV per day for 3 days, followed by a tapering regimen starting at 1mg/ kg/day. The patient’s general condition rapidly improved, with normalization of biological values and clinical stabilization.

Case 2 - 42-year-old patient diagnosed with classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

The second case is a 42-year-old patient diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma of mixed cellularity subtype, stage IV, IPS Score 5 (Hasenclever) with bone, splenic involvement, and bilateral cervical and axillary adenopathy. During the staging period, the patient consulted the emergency department with severe asthenia and inappetence, with daily diurnal and nocturnal febrile states. Laboratory findings showed an inflammatory syndrome with increased CRP, new pancytopenia, new cytolysis, and cholestasis, increased ferritin levels >11,000 ug/l and acute renal failure. Procalcitonin was increased (4.51µg/l.). Abdominal ultrasound showed splenomegaly and a liver of normal size and appearance. An HLH was suspected with considering as well CRS or septic shock as differential diagnoses. At this point, the SH score was 252 points, implying a 99% chance of HLH. Antibiotic treatment was started, as well as the pre-phase chemotherapy with prednisone 100 mg p.o. for five days, and blood transfusion. 48 hours after arrival, the patient had undergone the final staging examinations, and treatment for Hodgkin’s lymphoma was started. Due to hemodynamic instability, the patient was transferred to intensive care unit, where he received one cycle of the ABVD chemotherapy protocol (Doxorubicin, Bleomycin, Vinblastine and Dacarbazine) at an adapted dose to renal and hepatic function. The patient’s biological values and general condition rapidly improved.

Table 1: Pathologies associated with Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis syndrome. Adapted from:Adult hemophagocytic syndrome, Ramos et al. 2014 / Epidemiology, characteristics, and outcomes of adult hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in the USA, 2006–19: a national, retrospective cohort study, Abdelhay et al. 2023.

Table 2: HScore and therapeutic response of case 1 and case 2. Green depicts positive diagnostic features, red negative features. Normal range in brackets. Abbreviations: ABVD - chemotherapy protocol using Doxorubicin (A), Bleomycin (B), Vinblastine (V), Dacarbazine (D), OS - overall survival.

Discussion and Conclusion

These cases highlight the diversity of cancer associated secondary HLH etiologies as a rare complication in the context of advanced malignancies and immunotherapeutic interventions. The first case underscores the immunological sequelae of checkpoint inhibitor therapy, manifesting as hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) with a superimposed DIC, responding favourably to high-dose steroid therapy and IL-6R blockade with tocilizumab. In fact, recent studies suggest an incidence of 0.03%-0.4% of HLH secondary to immune checkpoint inhibitors with a mortality rate of up to 50% [15]. The second case illustrates the challenge of diagnosing HLH in the setting of advanced Hodgkin’s lymphoma, treated by the initiation of chemotherapy, where the differential diagnosis includes CRS and sepsis. Both cases exemplify the critical need for vigilance and prompt management in patients presenting with hyperinflammation and multi-organ involvement.

These cases emphasize the importance of considering HLH in the differential diagnosis of patients with malignancy who develop systemic inflammatory symptoms without inflammatory focus, particularly when receiving immunomodulatory therapies. Fever accompanied by worsening cytopenia, should prompt laboratory assessment of ferritin and triglyceride levels, together with an emphasis on detecting the presence of hepato-splenomegaly during physical examination or radiological assessment due to its occurrence in nearly two-third of cases. Further laboratory assessments should encompass liver and kidney function tests together with complete coagulation tests including fibrinogen measurement. Cytokine profiling including plasma measurements of TNFa, IL1, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, and IFNg, together with circulating levels of soluble IL-2 receptors (sIL2R or sCD25), and CD163 are not mandatory and not validated for management decisions, however, along with bone marrow examination, they might be considered for research purposes. The rapid improvement with targeted treatments demonstrates the efficacy of timely intervention, albeit highlighting the necessity for continued research into the optimal diagnosis and management strategies for HLH in the oncologic setting. Moreover, these cases underline the importance of rare but fatal side effects of novel treatments for cancer, where the benefits must be balanced against the potential for severe immune-related adverse events.

Declaration

Conflict of interest: Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Consent for Publication: Obtained from both patients.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available upon request.

Competing Interests: None.

Prof Alessandra Curioni-Fontecedro declares:

Consultation/advisory role: Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daichii Dankyo, Janssen, Medscape, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Roche/Genentech, Takeda.

Talk in a company’s organized public event: Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Foundation Medicine, Jannsen, Medscape, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Roche/Genentech, Takeda

Receipt of grants/research supports: (Sub)investigator in trials (institutional financial support for clinical trials) sponsored by Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Roche/Genentech Funding: No external funding sources.

Authors’ Contribution: All authors contributed equally.

Acknowledgments: We thank our healthcare team for their support.

Authors’ Interests: No competing interests.

Footnotes: None.

References

- Abdelhay A, Mahmoud AA, Al Ali O, Hashem A, Orakzai A, et al (2023) Epidemiology, characteristics, and outcomes of adult haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in the USA, 2006–19: a national, retrospective cohort study. eClinicalMedicine [Internet]. 62:102143.

- Jordan MB, Allen CE, Greenberg J, Henry M, Hermiston ML, et al. () Challenges in the diagnosis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: Recommendations from the North American Consortium for Histiocytosis (NACHO). Pediatr Blood Cancer [Internet]. 66: e27929.

- Onkopedia [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jan 14]. Hämophagozytische Lymphohistiozytose (HLH).

- Novotny F, Simonetta F, Samii K, Chalandon Y, Serratrice J. (2017) Syndrome hémophagocytaire réactionnel. Rev Med Suisse [Internet]. 579:1797–803.

- Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zerón P, López-Guillermo A, Khamashta MA, et al (2004) Adult haemophagocytic syndrome. The Lancet [Internet]. 383:1503–16.

- Mosser DM, Edwards JP. (2008) Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat Rev Immunol [Internet]. 8:958–69.

- Allen CE, Yu X, Kozinetz CA, McClain KL. (2008) Highly elevated ferritin levels and the diagnosis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer [Internet]. 50:1227–35.

- Henter J, Horne A, Aricó M, Egeler RM, Filipovich AH, Imashuku S, et al. (2007) HLH‐2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer [Internet]. 48:124–31.

- Score [Internet]. Hôpital Saint-Antoine AP-HP. [cited 2024 Jan 14].

- Gars E, Purington N, Scott G, Chisholm K, Gratzinger D, et al. (2018) Bone marrow histomorphological criteria can accurately diagnose hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Haematologica [Internet]. 103:1635–41.

- Strauss R, Neureiter D, Westenburger B, Wehler M, Kirchner T, et al (2004) Multifactorial risk analysis of bone marrow histiocytic hyperplasia with hemophagocytosis in critically ill medical patients A postmortem clinicopathologic analysis. Crit Care Med [Internet]. 32:1316.

- Chellapandian D, Das R, Zelley K, Wiener S, Zhao H, et al. (2013) Treatment of Epstein Barr virus-induced haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with rituximab-containing chemoimmunotherapeutic regimens. Br J Haematol [Internet]. 162:376–82.

- Hayden A, Park S, Giustini D, Lee AYY, Chen LYC. (2016) Hemophagocytic syndromes (HPSs) including hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) in adults: A systematic scoping review. Blood Rev [Internet]. 30:411–20.

- Johnson TS, Terrell CE, Millen SH, Katz JD, Hildeman DA, et al (2014) Etoposide selectively ablates activated T cells to control the immunoregulatory disorder hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. J Immunol Baltim Md 1950 [Internet]. 192:84–91.

- Özdemir BC, Latifyan S, Perreau M, Fenwick C, Alberio L, et al. (2020) Cytokine-directed therapy with tocilizumab for immune checkpoint inhibitor-related hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Ann Oncol [Internet]. 31:1775–8.

- Cox MF, Mackenzie S, Low R, Brown M, Sanchez E, Carr A, Carpenter B, Bishton M, Duncombe A, Akpabio A, Kulasekararaj A, Sin FE, Jones A, Kavirayani A, Sen ES, Quick V, Dulay GS, Clark S, Bauchmuller K, Tattersall RS, Manson JJ; HiHASC group. Diagnosis and investigation of suspected haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults: 2023 Hyperinflammation and HLH Across Speciality Collaboration (HiHASC) consensus guideline. Lancet Rheumatol. 2024 Jan;6(1):e51-e62.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.