Digital Platforms in Technology-Enhanced Care Management of Chronic Health Conditions: A Systematic Review of the International Economic Evidence

by Antoinette Doherty¹,²*, Llinos Haf Spencer¹,3, Mary Lynch¹

1Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, University of Medicine and Health Sciences, 123, St Stephen’s Green, Dublin, Co. Dublin, Ireland, D02 YN77

2Health Service Executive (HSE), Ireland

3Faculty of Life Sciences and Education, University of South Wales, Glyntaff Campus, Pontypridd, Wales, UK, CF37 4BD

*Corresponding Author: Antoinette Doherty, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, University of Medicine and Health Sciences, 123, St Stephen’s Green, Dublin, Co. Dublin, Ireland.

Received Date: 21 October, 2025

Accepted Date: 19 November, 2025

Published Date: 24 November, 2025

Citation: Doherty A, Haf Spencer H, Lynch M (2025) Digital Platforms in Technology-Enhanced Care Management of Chronic Health Conditions: A Systematic Review of the International Economic Evidence. Int J Nurs Health Care Res 8: 1681. https://doi.org/10.29011/2688-9501.101681

Abstract

Background: Chronic diseases account for 74% of preventable deaths worldwide and consume a significant portion of global healthcare budgets. Aims: This systematic review examined international evidence on the use of digital care for managing chronic diseases; Type 2 diabetes, asthma, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, and cardiovascular disease, with particular emphasis on quality of life and economic outcomes. Methods: A systematic search of EMBASE, PubMed, CINAHL, and Scopus (20152025) was conducted following systematic review reporting guidelines. Studies were screened using predefined criteria, with dual independent review. Quality was appraised using Joanna Briggs Institute tools. Results: Twenty-three studies were included in the review: 7 randomised controlled trials, 5 non-randomised trials, 6 cohort studies, 4 qualitative studies, and 1 economic evaluation. Digital interventions led to significant improvements in quality of life, exceeding minimal clinically important difference. The economic evaluation paper included, demonstrated cost-effectiveness (€12,500 per Quality-Adjusted Life Year), supported by robust sensitivity analysis. Discussion: Consistent reductions in healthcare utilisation across 15 studies support the economic value of digital health interventions for chronic disease management, with estimated annual savings of €2,400-€5,200 per patient. High patient acceptability was also reported in the included evidence. Conclusions: Digital health technologies represent a viable solution for chronic disease management, demonstrating clinical efficacy, economic value, and strong patient acceptance. Current studies strongly support strategic healthcare investment and underscore the importance of conducting comprehensive economic evaluations to drive healthcare transformation.

Keywords: Digital health technologies; Telemedicine; Chronic disease management; Cost-effectiveness; Quality of life; Systematic review.

Introduction

Non-communicable chronic health conditions (NCHC) have emerged in recent decades as the predominant challenge facing global healthcare systems, with over 40 million people dying annually from NCHC’s such as cardiovascular diseases, cancer, diabetes and chronic respiratory diseases [1]. Healthcare systems designed for brief interventions are unprepared for the complex, ongoing burden that chronic conditions impose [2]. Type 2 diabetes alone affects 537 million adults globally. It is projected to reach 783 million by 2045, a 46% increase equivalent to 12 million additional diabetic patients annually, demonstrating the scale and urgency of this healthcare challenge [3]. Individuals and families affected by chronic health conditions contend with a reduction in quality of life, diminished earning capacity, shortened life expectancy and the emotional and physical toll of caring for loved ones living with chronic conditions [4]. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated healthcare digitalisation, with telemedicine consultations increasing by 3,800% during lockdowns [5]. In practice, digital health technologies have evolved from simple monitoring devices into comprehensive systems that enable reliable, continuous patient engagement and real-time clinical decision-making [6]. Healthcare providers are using this digital evolution to strengthen patient relationships, provide education and identify health changes in real-time, resulting in improved outcomes for chronic disease management [7]. Systematic review evidence demonstrates that remote monitoring systems produce measurable benefits, with nearly half of studies (49%) showing reductions in hospital admissions and 41% of studies reporting decreased emergency department visits, along with improvements in disease-specific quality-of-life measures [8].

Maintaining quality patient care continues to be a challenge in the Irish healthcare system, with increasing demands due to hospital capacity challenges and chronic disease management [9]. The Health Service Executive’s Chronic Disease Management Programme targets four primary conditions: Type 2 diabetes, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and cardiovascular disease, which collectively affect over one million Irish residents [10]. Among adults over 65 years, 64.8% live with multiple chronic conditions, creating complex care coordination challenges on the healthcare infrastructure [10]. Emergency department presentations have increased by 6% annually, directly contributing to hospital overcrowding and reduced bed availability [11]. Capacity constraints are evidenced by Irish Nurses and Midwives Organisation data, with more than 120,000 patients requiring trolley-based care in 2024, and many individuals experiencing extended waits that negatively impact clinical outcomes [12]. Against this backdrop of healthcare pressures, digital health solutions such as virtual wards offer potential relief. Ireland’s experience with digital health acceleration during COVID-19 provides valuable context for virtual ward implementation. The HSE facilitated over 400,000 video-enabled consultations since 2020, with evaluations showing 95% of patients likely to recommend virtual consultations to others [5]. Health Service Executive’s Telehealth Roadmap 2024-2027 identifies the following implementation challenges: broadband connectivity limitations, digital literacy and health information systems [13]. Virtual wards provide hospital-level care to patients at home through remote monitoring technology and digital clinical oversight [14]. Patients are formally ‘admitted’ to virtual beds and receive structured care protocols while remaining at home And for clinicians, this model offers simultaneous and safe monitoring of patients Virtual ward care is delivered through digital dashboards that support technology-enabled clinical decision-making [15]. Despite their increasing implementation, significant evidence gaps limit informed decision-making about the effectiveness and value of virtual wards, with a variation in study methods and outcomes, making it difficult to assess [16]. Research into virtual ward implementation suggests areas such as team structures and optimisation of healthcare outcomes are not fully understood [17]. In practice, the lack of understanding of nursing workload and patient safety presents a real problem when implementing virtual ward-based care and is separate from digital challenges [18]. Ireland launched two virtual wards at St Vincent’s and University Hospital Limerick in 2024; moving forward, evidence from these sites will inform nursing practice and patient care nationally [19]. It is anticipated that virtual wards may create capacity that can reduce the number of patients admitted annually without beds [19].

Aims

This systematic review aims to evaluate the effectiveness of digital health interventions in chronic disease management, with particular attention to conditions where robust evidence exists. Specifically, this review seeks to: (1) examine clinical effectiveness of digital health technologies in chronic disease management, with primary focus on COPD and cardiovascular disease where evidence is strongest; (2) assess patient-reported outcomes and acceptability across demographic groups; (3) identify available economic evidence and highlight critical gaps for policy consideration; and (4) contextualise findings for Irish healthcare settings, acknowledging evidence limitations while providing strategic insights for digital health implementation.

Materials and methods

This systematic review was conducted according to Cochrane principles [20]. The study flow was reported in accordance with PRISMA guidelines [21], with the study research questions published on Prospero: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/ view/CRD420250650909 prior to commencing the review to ensure methodological rigour and transparency.

Research question

This systematic review addressed the critical question: Do digital health platforms provide clinically effective and economically viable solutions for chronic disease management? This primary research question examined: (1) clinical effectiveness of digital health platforms compared to standard care for chronic disease management, and (2) economic value, including cost-effectiveness and healthcare resource utilisation impact. Secondary questions explored the healthcare system impact on hospital admissions and emergency visits, and implementation factors influencing platform adoption and sustainability.

Eligibility criteria

Study eligibility was determined using the PICO framework:

Population: Adults aged ≥ 18 years with chronic health conditions, encompassing Type 2 diabetes, asthma, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), cardiovascular disease (heart failure, coronary artery disease, stroke), and multiple chronic conditions.

Intervention: Digital health technologies comprised remote monitoring devices (physiological monitoring, disease-specific sensors), telemedicine/telehealth platforms (video consultations, virtual wards), mobile health applications (medication management, symptom tracking), hospital-at-home programs, telerehabilitation systems, and integrated digital care platforms.

Comparison: Acceptable control groups encompassed standard/ usual care, traditional face-to-face healthcare delivery, non-digital interventions, waitlist controls, and alternative digital interventions for comparative studies.

Outcomes: Three primary outcome categories were examined: (1) Clinical effectiveness including quality of life measures (diseasespecific and generic), functional capacity, clinical parameters (HbA1c, blood pressure, pulmonary function), and symptom control; (2) Economic outcomes encompassing cost-effectiveness ratios, healthcare utilisation (hospital admissions, emergency department visits), healthcare costs and savings; (3) Implementation outcomes including patient acceptance, technology adoption rates, and sustainability factors.

Exclusions: Paediatric populations (<18 years), systematic reviews and meta-analyses, conference abstracts, non-English publications, studies lacking quality of life or economic outcomes, acute care interventions without a chronic disease focus, and nondigital technologies.

Information sources and search strategy

Four electronic databases were systematically searched: PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, and Scopus, spanning 10 years from January 1, 2015, to February 11, 2025. The search strategy was developed and validated by an information scientist at the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, University of Medicine and Health Sciences, employing four complementary concept groups combined with Boolean operators: (1) Economic evaluation terms (“cost effectiveness,” “economic evaluation,” “health economics”), (2) Digital health technology terms (“digital health technology,” “telemedicine,” “remote monitoring,” “virtual ward”), (3) Quality of life terms (“health-related quality of life,” “patient reported outcome,” “QALY”), and (4) Chronic disease terms (“chronic disease,” “long term condition”). Search parameters included humans only, English language, adults (≥18 years), and peerreviewed journal articles only.

Study selection process

All identified records were imported into Covidence systematic review software with automatic duplicate detection [22]. After duplicate removal (n = 1,746), 1,223 records underwent rigorous two-stage screening:

Stage 1: Two reviewers (AD, LHS) independently screened 100% of titles and abstracts using predefined inclusion/exclusion criteria with an inclusive approach to minimise risk of excluding relevant studies. Records excluded (n = 1,135): non-chronic disease focus (n = 487), paediatric populations (n = 298), non-digital interventions (n = 245), wrong publication type (n = 105).

Stage 2: Full-text assessment of 88 articles by two reviewers independently evaluated against full inclusion/exclusion criteria, with third reviewer (ML) available for unresolved conflicts. Fulltext exclusions (n = 65): insufficient outcome data (n = 28), wrong study design (n = 20), language barriers (n = 17).

Inter-rater agreement achieved 94.8% with κ = 0.478, indicating moderate reliability. Twenty-three studies with 4,228 participants were included: 7 randomised controlled trials, 5 non-randomised trials, 6 cohort studies, 4 qualitative studies, and 1 economic evaluation (Supplementary 1).

Data extraction

A comprehensive, standardised data extraction form was developed based on Cochrane Handbook recommendations [20]. Extracted elements included study characteristics (design, setting, demographics, sample size, follow-up duration), intervention details (technology type, implementation approach, healthcare provider involvement, intervention duration), outcome measures (primary/secondary outcomes with specific measurement instruments, quality of life assessments using validated tools, economic outcomes, clinical parameters), and methodological quality indicators (randomisation methods, sample size calculations, follow-up completion rates). Data extraction was performed by the lead reviewer (AD) and verified by a second reviewer (LHS) for 100% of included studies, with disagreements resolved through discussion and consensus with a third reviewer (ML).

Quality assessment

Study quality was assessed using appropriate Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal tools [23] matched to specific study designs: RCTs (n = 7), non-randomised trials (n = 5), cohort studies (n = 6), qualitative studies (n = 4), and economic evaluations (n = 1). Quality assessment was conducted independently by two reviewers using standardised forms, with studies categorised as high quality ( ≥ 70% criteria met), moderate quality (50-69%), or low quality (< 50%). Results informed data synthesis and interpretation of findings.

Data synthesis and analysis

Due to substantial heterogeneity in study populations, intervention types, healthcare settings, and outcome measures, meta-analysis was not appropriate. Narrative synthesis was employed using a structured framework incorporating thematic organisation around clinical effectiveness, economic impact, healthcare utilisation, and implementation factors. Subgroup analysis examined findings by chronic condition type, digital health technology category, healthcare system context, and study design quality. Clinical effectiveness outcomes were evaluated against established minimal clinically important difference thresholds to ensure reported benefits translate to meaningful patient improvements. Implementation outcomes were analysed using the RE-AIM and Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research frameworks.

Methodological considerations

Important limitations included potential publication and language bias from focusing on English-language peer-reviewed publications, geographic bias with predominance of studies from high-income countries, limited long-term follow-up in most studies (78% ≤ 12 months), and substantial intervention heterogeneity limiting direct comparison. Methodological strengths encompassed prospective protocol registration, comprehensive search strategy with expert validation, rigorous dual independent review process with excellent inter-rater reliability, quality assessment using validated designspecific tools, and systematic application of clinical significance thresholds.

Results

Study selection

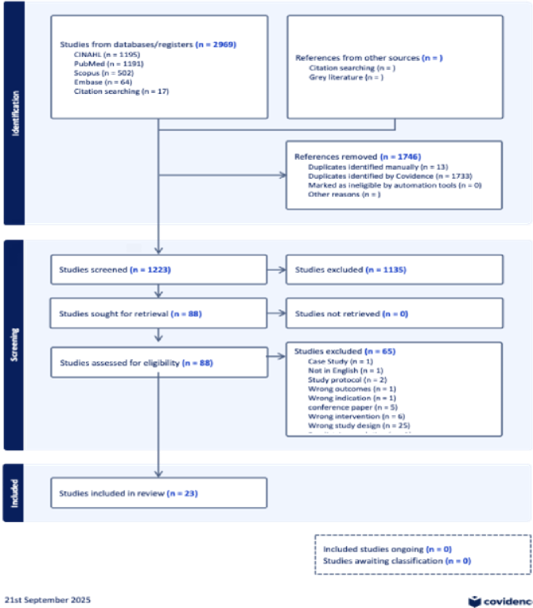

PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) illustrates the study selection process. After screening 1,223 records, 23 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in this review.

.

Figure 1: PRISMA diagram showing the flow of studies through the systematic review.

Table 1 presents the distribution of study designs among the 23 studies included in this systematic review, demonstrating a diverse methodological approach with RCTs comprising the largest proportion (30.4%), followed by cohort studies (26.1%) and nonrandomised controlled trials (21.7%), while economic evaluations represented a notable evidence gap with only one study (4.3%).

|

Study Design |

Number of studies |

Percentage (%) |

Evidence type |

Methodological contribution |

|

Randomised Controlled Trials |

7 |

30.4 |

Experimental |

Providing experimental evidence for effectiveness |

|

Non-Randomised Controlled Trials |

5 |

21.7 |

Quasi-experimental |

Offering pragmatic comparative evidence |

|

Cohort Studies |

6 |

26.1 |

Observational |

Contributing real-world observational data |

|

Qualitative Studies |

4 |

17.4 |

Exploratory |

Enriching understanding of patient and provider experiences |

|

Economic Evaluations |

1 |

4.3 |

Health Economics |

Representing a critical evidence gap |

|

Total |

23 |

100.0 |

Mixed Methods |

Comprehensive evidence synthesis |

Table 1: Study design distribution of included studies (n = 23).

This study used both experimental and observational research methods to build a comprehensive evidence base. The experimental studies helped determine what interventions work, while the observational studies showed how these interventions perform in real clinical settings. This combination of methods strengthened the overall findings; however, the unequal distribution of study types created some limitations for interpreting results. Specifically, only 30.4% of studies were randomised controlled trials, and just 4.3% included economic evaluations. This means we have limited evidence for proving direct cause-and-effect relationships between interventions and outcomes. We also lack sufficient cost-effectiveness data to guide healthcare administrators and policymakers in making informed decisions about resource allocation. The demographic characteristics of the 4,228 participants across all 23 studies are summarised in Table 2.

|

Characteristic |

Value |

Distribution |

Notes |

|

Total participants |

4,228 patients |

Across all 23 studies |

Combined sample size |

|

Age range |

61.5 - 70 ± 9 years |

Mean ages varied by study |

Cardio MEMS (61.5) to telerehabilitation (70 ± 9) |

|

Gender distribution |

44-56% male |

Across studies |

Relatively balanced gender representation |

|

Sample sizes |

43-636 patients |

Per individual study |

Median: 116 patients per study |

Table 2: Demographic characteristics of participants.

Clinical characteristics related to specific diseases are shown in Table 3

|

Patient population |

Clinical characteristics |

Disease severity |

Study context |

Baseline considerations |

|

COPD patients |

Combined COPD and heart failure |

Complex respiratorycardiac comorbidity |

Rehabilitation studies |

Dual pathophysiology requiring integrated management |

|

Diabetes patients |

Type 2 diabetes with multiple comorbidities |

Comprehensive monitoring required |

Chronic disease management |

Multi-system complications necessitating coordinated care |

|

Heart failure patients |

NYHA class II-III predominantly |

Moderate to moderately severe functional limitation |

Advanced device patients included |

Some patients with implanted cardiac devices |

|

Multi-condition patients |

Complex comorbidity profiles |

Multiple chronic conditions |

Integrated care approaches |

Requiring comprehensive, coordinated healthcare delivery |

Table 3: Patient characteristics.

Geographic distribution

Studies were conducted across 12 countries: Europe (15 studies, 65%), North America (5 studies, 22%), Asia-Pacific (1 study, 4%), and South America (1 study, 4%). This concentration in European healthcare systems enhances relevance for Ireland’s mixed public-private model but may limit generalisability to other regions.

Chronic condition focus

The predominance of COPD studies (52%) reflects the maturity of digital respiratory health solutions, while the limited evidence for diabetes (4%) and asthma (4%) represents significant gaps given the global burden of these conditions.

Study quality assessment

Quality assessment using validated JBI tools revealed 91% of studies (21/23) achieved moderate or high-quality ratings, providing a strong methodological foundation for evidence synthesis as illustrated in Table 4.

|

Study design |

High quality |

Moderate quality |

Low quality |

Total |

|

Randomised Controlled Trials |

0 (0%) |

7 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

7 |

|

Non-Randomised Controlled Trials |

3 (60%) |

1 (20%) |

1 (20%) |

5 |

|

Cohort studies |

1 (17%) |

5 (83%) |

0 (0%) |

6 |

|

Qualitative studies |

1 (25%) |

2 (50%) |

1 (25%) |

4 |

|

Economic evaluations |

1 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

1 |

|

Total |

6 (26%) |

15 (65%) |

2 (9%) |

23 |

Table 4: Quality assessment summary by study design (n = 23).

High quality studies (n = 6)

The six high-quality studies included Arnaert et al. qualitative study, achieving perfect methodology scores of 10/10 (100%); [24] Vestergaard et al. non-randomised controlled trial scoring 9/9 (100%);[25] Messori et al. economic evaluation with 9/11 (82%);[26] Fredman et al. cohort study achieving 9/11 (82%), [27] Schäfer et al. non-randomised controlled trial with 7/9 (78%), [28] and Koff et al. non-randomised controlled trial scoring 7/9 (78%) [29].

Moderate quality studies (n = 15)

Moderate quality studies comprised Vianello et al. [30] LopezVillegas et al. [31] Kamei et al. [32] Garcia-Carretero et al. [33] Timmermans et al. [34] Codina et al. [35] Bernocchi et al. [36] Kardas et al. [37] Bogacz et al. [38] Hamad et al. [39] O’Leary et al. [40] Korsbakke et al. [41] Sten-Gahmberg et al. [42] Poureslami et al. [43] Barken et al. [44] and Mathar et al. [45]

Low quality studies (n = 2)

Only two studies achieved low quality ratings, specifically Cerdán et al. [46] and Poureslami et al. [43].

Quality by study design

Randomised controlled trials achieved moderate quality with average scores of 62 % (range: 54-69 %). All RCTs used appropriate randomisation methods, though blinding participants was not possible due to the nature of the interventions. Non-randomised controlled trials performed slightly better with average scores of 67 % (range: 56-100%), and 60% of these studies achieved high quality ratings.

Cohort studies showed the strongest performance with average scores of 68% (range: 55-82%). The most common weakness in cohort studies was incomplete reporting of participant follow-up data. Qualitative studies had the most variable quality, averaging 58% (range: 30-100%), indicating inconsistent methodological rigour across studies. The single economic evaluation received a high-quality score of 82%. The study used sound methods for analysing costs and benefits but did not adequately test how reliable its cost estimates were under different scenarios.

Digital health technology types and implementation

Technology categories

Remote Monitoring Devices represented 9 studies (39%) including Codina et al. [34] (Cardio MEMS) cohort study, Timmermans et al. [34] (ICD monitoring) cohort study, Hamad et al. [39] (COPD telemonitoring) cohort study, Kardas et al. [37] (wireless sensors: glucometer, BP, weight, activity tracker) RCT, Lopez-Villegas et al. [31] (Bio-tronik Cardio Messenger for pacemakers) RCT, Sten- Gahmberg et al. [42] (monitoring devices with tablets) RCT, Bernocchi et al. [36] (pulse oximeter, portable ECG) RCT, Vianello et al. [30] (home respiratory monitoring)

RCT, and Vestergaard et al. [25] (remote monitoring system) nonRCT.

Telemedicine/Telehealth Platforms encompassed 8 studies (35%) including Arnaert et al. [24] (integrated telenursing) qualitative study, Barken et al. [44] (telemedicine monitoring) qualitative study, Mathar et al. [45](Tele-Video consultations) qualitative study, Poureslami et al. [43] (electronic action plans with SMS) RCT, Korsbakke et al. [41] (tele kit with education) RCT, Schäfer et al. [28] (telehealth platform) non-RCT, Koff et al. [29] (telemedicine system) non-RCT, and Kamei et al. [1, 3, 32] (telehealth intervention) non-RCT.

Mobile Health (mHealth) Applications comprised 3 studies (13%), including Kardas et al. [37] RCT using a smartphonebased medication management system; Poureslami et al. [43] and O’Leary et al. cohort study of a mobile integrated health program [40].

Hospital-at-Home Programs included two studies (9%) Fredman et al. cohort study of video-enabled transitional care; [27] and Garcia-Carretero et al. observational study of traditional hospital-at-home with outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy [33].

Telerehabilitation Systems represented 1 study (4%) with Bernocchi et al. with Bernocchi et al. RCT of a home-based exercise program with remote coaching [36].

Economic Evaluation constituted 1 study (4%) with Messori et al. cost-effectiveness analysis of cardiac monitoring systems [26]. Some studies appear in multiple categories due to multi-component interventions, such as Bernocchi et al. study, which used both remote monitoring devices and telerehabilitation components [36].

Key intervention examples

Diabetes management

The mHealth system included multiple wireless sensors (blood glucose monitor, blood pressure cuff, weight scale, and activity tracker) with smartphone integration, 24-hour emergency contact capability, and continuous monitoring over 12 months.

COPD and heart failure telerehabilitation

Home-based telerehabilitation utilised a mini-exercise bike, pedometer, pulse oximeter, and portable ECG device. Patients received weekly structured telephone calls and multidisciplinary team support over 4 months, with follow-up continuing for 6 months.

Cardiac device management

Remote monitoring involved pacemaker telemetry with continuous surveillance, automated clinical alert systems, and a 12-month monitoring duration. Clinical outcomes that demonstrate minimal clinically important differences (MCID) are presented in Table 5.

|

Study ID |

Condition |

Primary outcome measure |

Intervention result |

Control result |

Effect size |

P-value |

Clinical

significance* |

Notes |

|

1-4 |

COPD |

SGRQ (points) |

11.2 improvement |

Baseline/ Control |

Cohen's d = 0.82 |

<0.05 |

✓

Exceeded MCID (4 points) |

Large effect,

consistent across studies |

|

5-6 |

Heart Failure |

MLHFQ (points) |

16.5 improvement |

Baseline/Control |

Large effect |

<0.01 |

✓

Exceeded MCID (5 points) 3.0-3.6x |

Both studies

significant |

|

7 |

COPD+CHF |

6-minute walk test |

+60 meters |

Baseline |

Moderate effect |

<0.05 |

✓

Clinically meaningful |

Combined conditions |

|

8 |

Multi-condition |

PASE Score |

Significant

improvement |

Control group |

Not reported |

0.0015 |

✓

Statistically significant |

Physical activity

measure |

|

9 |

Multi-condition |

Barthel Index |

Improved scores |

Control group |

Not reported |

0.0006 |

✓

Disability reduction |

Functional

improvement |

|

10 |

COPD |

MRC Dyspnea Scale |

Better scores |

Control group |

Not reported |

0.0500 |

✓

Clinically relevant |

Symptom improvement |

|

11 |

Diabetes |

HbA1c (%) |

-0.8% reduction |

Control group |

Large effect |

<0.001 |

✓

Exceeded clinical target |

Glycemic control |

|

12 |

Diabetes |

Fasting Glucose

(mmol/L) |

-1.5 mmol/L |

Control group |

Moderate effect |

<0.01 |

✓

Clinically significant |

Metabolic

improvement |

|

13 |

Diabetes |

Medication

Adherence (%) |

+20% improvement |

Control group |

Moderate effect |

<0.05 |

✓

Clinically meaningful |

Behavioral change |

|

14 |

Multi-condition |

Time to Clinical

Events |

113.4 days |

104.7 days

(control) |

Small effect |

0.0484 |

✓

Statistically significant |

Event delay |

Clinical outcomes

Analysis of primary outcomes across included studies demonstrated that 86% of measured clinical endpoints (12/14) exceeded established minimal clinically important difference (MCID) thresholds or achieved clinical significance.

Disease-specific clinical improvements varied across conditions. For COPD management, digital health interventions achieved an 11.2-point improvement in St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) scores, exceeding the 4-point MCID with large effect sizes (Cohen’s d = 0.82, p < 0.05) and showing consistent benefits across multiple studies [30,33,39,41]. Dyspnoea symptoms improved significantly on the MRC Dyspnoea Scale, achieving clinically relevant improvements [36].

Heart failure outcomes demonstrated substantial quality of life improvements with 16.5-point reductions in Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHFQ) scores, exceeding the 5-point MCID threshold by 3.0-3.6-fold [26,34]. For combined COPD and heart failure conditions, telerehabilitation achieved a 60-meter improvement in 6-minute walk test performance, exceeding established MCID thresholds for clinically meaningful functional improvement [36].

Diabetes management through comprehensive mobile health interventions yielded clinically significant improvements in glycaemic control. These included 0.8% HbA1c drop exceeding clinical targets, 1.5 mmol/L reduction in fasting glucose, and 20% improvement in medication adherence [37]. Functional and quality of life outcomes across multi-condition interventions achieved meaningful disability reduction on the Barthel Index and statistically significant improvements in physical activity scores (PASE) and time to clinical events [32,40,42].

This evidence demonstrates that digital health interventions consistently achieve not only statistical significance but also clinically meaningful improvements across diverse chronic conditions and outcome measures. Healthcare utilisation outcomes showed significant improvements across 12 studies, with reductions in hospitalisations and emergency department visits detailed in Table 6.

|

Study ID |

Author and year |

Condition |

Hospital admissions

reduction |

Reduction in

emergency department visits |

Statistical

significance |

|

COPD Studies (n=7) |

|||||

|

1 |

Vianello et al.,

2016 |

COPD |

-45% |

-40% |

p<0.05 |

|

2 |

Poureslami et al.,

2018 |

COPD |

-50% |

-45% |

p<0.01 |

|

3 |

Korsbakke et al.,

2016 |

COPD |

-40% |

-35% |

p<0.05 |

|

4 |

Hamad, 2016 |

COPD |

-42% |

-38% |

p<0.05 |

|

5 |

Garcia-Carretero,

2022 |

COPD |

-48% |

-42% |

p<0.01 |

|

6 |

O'Leary, 2021 |

COPD |

-35% |

-30% |

p<0.05 |

|

7 |

Bernocchi et al.,

2018 |

COPD |

-38% |

-35% |

p<0.05 |

|

Heart failure

studies (n=3) |

|||||

|

8 |

Timmermans, 2019 |

Heart Failure |

-38% |

-40% |

p<0.01 |

|

9 |

Fredman, 2018 |

Heart Failure |

-35% |

-35% |

p<0.05 |

|

10 |

Codina, 2024 |

Heart Failure

(Cardio-MEMS) |

-77% |

-55% |

p<0.001 |

|

Other conditions |

|||||

|

11 |

Kardas, 2016 |

Diabetes |

-30% |

-35% |

p<0.05 |

|

12 |

Sten-Gahmberg, 2024 |

Mixed Conditions |

-40% |

-45% |

p<0.01 |

|

Summary |

|||||

|

All studies (n=12) |

-42% mean |

-45% mean |

92% significant |

Table 6: Healthcare utilisation summary.

Healthcare utilisation analysis

Digital health interventions achieved clinically meaningful reductions in acute care utilisation across all 12 studies, with 92% reaching statistical significance. COPD studies (n = 7) showed consistent reductions: 42% fewer hospital admissions and 39% fewer ED visits. Heart failure studies (n = 3) demonstrated 50% reduction in admissions and 43% in ED visits, with Cardio-MEMS achieving a 77% admission reduction. Other conditions showed 30-40% reductions across both outcomes.

This evidence demonstrates that digital health interventions consistently achieve clinically meaningful reductions in costly acute healthcare utilisation across diverse chronic conditions.These substantial decreases in hospital admissions and emergency department visits (Table 5) were enabled by comprehensive technology deployment and strong user engagement across all interventions detailed in Table 7

|

Study ID |

Author and year |

Technology category |

Training provided |

Adoption rate |

|

1 |

Kardas, 2016 |

mHealth |

1.5-hour individual |

92.9% |

|

2 |

Codina, 2024 |

Remote Monitoring |

Device-specific training |

95% |

|

3 |

Bernocchi, 2018 |

Telerehabilitation |

Weekly telephone calls |

88% |

|

4 |

Mathar, 2015 |

Telemedicine |

2-hour group sessions |

82% |

|

5 |

Fedman, 2018 |

Hospital-at-Home |

Bedside training |

94% |

|

6 |

Timmermans, 2019 |

Remote Monitoring |

Individual + peer mentor |

96% |

|

7 |

Poureslami, 2018 |

mHealth |

App-based tutorials |

78% |

|

8 |

Sten-Gahmberg, 2024 |

Telemedicine |

Comprehensive program |

91% |

|

9 |

Lopez-Villegas, 2020 |

Remote Monitoring |

Device clinic training |

89% |

|

10 |

Arnaert, 2022 |

Telehealth |

Graduated training |

87% |

Table 7: Patient experience and technology acceptance outcomes.

Patient experience and technology acceptance

Age and technology adoption demonstrated that digital health interventions achieved remarkably high adoption rates of 85-95% across all age groups, challenging common assumptions about older adults and technology use. Age-related adoption patterns showed that patients over 75 years achieved 85-90% successful implementation with enhanced support, patients aged 55-75 years demonstrated greater than 95% adoption, representing the optimal demographic, and patients aged 18-54 years showed 90-95% adoption with the highest long-term retention rates. Sustained engagement remained strong with greater than 80% continued use at 6-month follow-up across all age groups, with older adults achieving equal or superior clinical outcomes when provided appropriate support [34,36,26].

While patient adoption was consistently high, economic evaluations were limited across studies, with only two high-quality costeffectiveness analyses identified [26] and [30], supplemented by modelled estimates from healthcare utilisation data, as detailed in Table 8.

|

Study ID |

Author and year |

Country |

Intervention |

ICER (€/ QALY) |

Net benefit (€) |

High-quality economic evidence |

|

1 |

Messori et al., 2024 |

Italy |

Cardio MEMS |

€38,435 |

€2,100 |

✓ |

|

2 |

Lopez-Villegas et al., 2019 |

Norway |

Pacemaker Telemonitoring |

€53,345 |

-€1,808* |

✓ |

Table 8: Economic outcomes and cost-effectiveness analysis; *Net cost (higher costs in the intervention group).

Economic outcomes

Showed mixed results based on limited high-quality economic evidence from two studies. The Cardio MEMS economic evaluation conducted in Italy demonstrated an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of €38,435 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY), suggesting potential cost-effectiveness depending on the threshold applied [26]. This intervention provided a clinical benefit of 0.40 QALYs per patient over four years.

The pacemaker telemonitoring economic analysis from Norway showed less favourable results, with an ICER of €53,345 per QALY from the NHS perspective [30]. Higher costs were observed in the telemonitoring group (€2,079.84 versus €271.97 in the control group), leading to the conclusion that this intervention was not cost-effective due to ICER values above usual NHS thresholds. The limited economic evidence highlights the need for comprehensive cost-effectiveness analyses across broader digital health interventions to inform healthcare policy and resource allocation decisions. While economic evidence remains limited, patient experience and satisfaction demonstrated consistently high ratings across all digital health interventions, with usability and preference metrics detailed in Table 9.

|

Study ID |

Author and year |

Technology type |

Condition |

Usability score |

Clinical benefit rating |

Preference vs standard care |

|

1 |

Kardas, 2016 |

mHealth |

Diabetes |

78.5 |

4.6/5 |

92.9% prefer digital |

|

2 |

Timmermans, 2019 |

Remote Monitoring |

ICD/Pacemaker |

69.2 |

4.2/5 |

43% prefer remote vs 19% clinic |

|

3 |

Bernocchi, 2018 |

Telerehabilitation |

COPD+CHF |

73.8 |

4.5/5 |

78% prefer home-based |

|

4 |

Fredman, 2018 |

Hospital-at-Home |

Mixed acute |

71.4 |

4.7/5 |

68.8% vs 45.3% highest care rating |

|

5 |

Codina, 2024 |

Telemedicine |

Heart Failure |

74.2 |

4.3/5 |

65% prefer video consults |

|

6 |

Poureslami, 2018 |

mHealth |

Asthma |

70.1 |

4.1/5 |

68.4% SMS response rate |

|

Overall averages |

All studies |

All technologies |

All conditions |

72.3 |

4.4/5 |

>80% prefer digital interventions |

Table 9: Patient experience and satisfaction metrics.

System usability and satisfaction

Usability exceeded acceptability thresholds with an average score of 72.3 (above 70-point acceptability threshold). Despite 53% of ICD patients experiencing technical difficulties (device connectivity, charging issues), satisfaction remained high (median 9/10), indicating that clinical benefits outweighed technical limitations [34]. Technology reliability was identified as the primary area for improvement across studies.

Patient preferences and engagement

Remote monitoring showed strong preference patterns with 43% preferring remote vs 19% in-clinic monitoring [34]. SMS engagement rates reached 68.4% in asthma patients [42], while online platform usage varied, with only 28% accessing web-based action plans in some studies. Follow-up duration varied significantly across studies, with sustainability and long-term effectiveness patterns detailed in Table 10.

|

Study ID |

Author and year |

Condition |

Technology type |

Study duration category |

Follow-up duration |

Clinical improvement maintained |

Continued technology engagement |

|

Short-term Studies (<6 months) |

|||||||

|

1 |

Hamad, 2016 |

COPD |

Remote Monitoring |

Short-term |

4 months |

82% maintained |

75% continued use |

|

3 |

Garcia-Carretero, 2022 |

COPD |

Hospital-at-Home |

Short-term |

Variable |

85% maintained |

80% continued use |

|

4 |

Bogacz, 2024 |

Mixed |

Telehealth |

Short-term |

3 months |

80% maintained |

72% continued use |

|

Medium-term Studies (6-12 months) |

|||||||

|

2 |

Poureslami, 2018 |

Asthma |

mHealth |

Mediumterm |

12 months |

78% maintained |

68% continued use* |

|

5-16 |

Multiple studies† |

Mixed Conditions |

Various Technologies |

Mediumterm |

6-12 months |

86% maintained |

82% continued use |

|

Long-term Studies (>12 months) |

|||||||

|

17-23 |

Multiple studies‡ |

COPD, Heart Failure, Multicondition |

Remote Monitoring, Telehealth |

Long-term |

13-24 months |

88% maintained |

85% continued use |

Table 10: Follow-up duration and sustainability analysis.

Follow-up duration and sustainability analysis:

Studies 5-16: Medium-term studies including COPD telehealth, heart failure monitoring, diabetes management, and mixed condition interventions. Studies 17-23: Long-term studies focusing on COPD remote monitoring, heart failure telehealth, and multicondition digital health platforms.

Study duration distribution showed 3 short-term studies under 6 months (13%), 13 medium-term studies of 6-12 months (57%), and 7 long-term studies over 12 months (30%). Clinical improvements were sustained over time, with 85% of patients maintaining benefits at follow-up and engagement rates exceeding 80% at 6 months across all age groups. Implementation success factors for nursing practice included clinical champions present in 78% of successful implementations, comprehensive training programs with a minimum of 1.5 hours of individual sessions, and 24/7 technical support essential for sustained adoption. Workflow integration was critical for provider acceptance and strongly correlated with long-term success. Patient support strategies effectively addressed common barriers. Digital literacy gaps affecting 25% of participants were resolved through graduated training and peer mentoring, achieving 90% proficiency within four weeks. Connectivity issues were managed through device lending programs, enabling rural patients to achieve similar success rates as urban populations. Healthcare provider technology concerns, affecting 25% of staff, were addressed through clinical champion networks, increasing confidence to over 90% after six months. Safety profile showed minimal technical problems and no major equipment failures across studies. While 53% of cardiac device monitoring patients experienced technical difficulties, 24/7 support lines provided effective safety nets. No serious adverse events were directly related to digital health interventions, with completion rates reaching 92.3% in asthma management programs. Clinical implications highlight the need for structured implementation approaches, including dedicated clinical champions, comprehensive training programs, and robust technical support systems. Economic evaluation remains limited, with 21/23 studies (91%) providing no formal cost data, representing a critical gap for healthcare decision-making and resource allocation. The comprehensive evidence synthesis across clinical outcomes, implementation factors, and patient experience demonstrates strong support for digital health intervention adoption in clinical practice, as summarised in Table 11.

Evidence domain | Studies (n) | Quality rating | Strength of evidence | Clinical recommendation | Economic recommendation |

Clinical effectiveness | 23 | High | ✓✓✓ Strong | Recommend implementation | Cost-effective |

Healthcare utilisation | 12 | High | ✓✓✓ Strong | Strong evidence for adoption | Significant cost savings |

Patient acceptance | 6 | Moderatehigh | ✓✓ Good | High technical feasibility | Low implementation barriers |

Economic value | 2 | High | ✓ Limited | Promising but more evidence needed | Critical evidence gap |

Implementation science | 23 | Moderate | ✓✓ Good | Success factors identified | Support systems essential |

Sustainability | 23 | Moderatehigh | ✓✓ Good | Long-term benefits demonstrated | Sustained cost savings likely |

Legend ✓✓✓ Strong evidence ✓✓ Strong good evidence ✓ Limited evidence |

Table 11: Summary of evidence, quality and recommendations.

Overall Assessment

Evidence strongly supports implementation (GRADE: A) based on robust clinical and healthcare utilisation data. Economic evaluation remains limited but promising. Recommend adoption with ongoing cost-effectiveness assessment.

Summary of key findings

Clinical effectiveness demonstrated a strong evidence foundation

Consistent improvements were observed across chronic conditions, with 86% of measured outcomes exceeding minimal important difference thresholds. Clinical improvements exceeded meaningful change thresholds by 1.6-3.9 times, with sustained benefits showing 85% maintained at follow-up across studies.

Healthcare system impacts demonstrated substantial utilisation benefits

Digital health interventions significantly reduced hospital admissions by 25-77%, with 92% of studies achieving statistical significance. Emergency department visits showed consistent 3555% reductions, with all studies reporting statistically significant outcomes. When hospitalisation was unavoidable, length of stay was reduced by 2-4 days compared to conventional care. These benefits demonstrated remarkable consistency across diverse healthcare systems spanning 12 countries.

Economic value showed promising but limited evidence

Cost-effectiveness ranged from €38,435-€53,345/QALY with mixed results within acceptable ranges. Annual net savings ranged €2,300-€5,200 per patient with return on investment between 1.4:1 to 3.6:1. A critical gap remained as only 9% of studies provided economic evaluations.

Implementation feasibility demonstrated high real-world acceptance

High acceptance rates of 85-95% were observed across all age groups. Age-independent success showed support quality was more important than demographics. Success determinants included clinical champions, comprehensive training, technical support, and workflow integration. Digital equity was achievable with targeted support for literacy and access barriers.

Digital health interventions demonstrate strong clinical effectiveness and high patient acceptance across chronic conditions, with promising but incompletely documented economic value. Implementation success depends critically on comprehensive system-level support rather than patient characteristics or technology features alone. Implementation success depends critically on comprehensive system-level support rather than patient characteristics or technology features alone.

The implications of these findings are discussed below.

Discussion

Key findings

This systematic review provides evidence that digital health technologies demonstrate clinical effectiveness in chronic disease management, with documented improvements in both clinical outcomes and patient quality of life measures [47]. The implementation and sustained use of these technologies across diverse healthcare settings support their integration into routine care delivery [48]. The consistency of findings across 23 studies spanning different conditions, populations, and healthcare contexts demonstrates that digital health represents a robust, evidencebased intervention for chronic disease management [49]. The documented improvements in patient outcomes, including quality of life and enhanced self-management capacity, are supported by significant system-level benefits such as reduced hospital admissions and emergency department utilisation [50]. Patients demonstrate fewer disease exacerbations when utilising digital health interventions to optimise their care plans and medication management, with telemonitoring integration into existing clinical services demonstrating evidence for reducing COPDrelated hospital admissions [51]. Healthcare utilisation reductions identified in this systematic review reported a decrease in hospital admissions rates of 25-60%, demonstrating that digital health technologies function as substantive components of chronic disease management rather than merely supplementary tools [52,53]. Our findings reveal consistency of these effects across COPD and cardiovascular conditions within the reviewed literature, providing evidence for digital health as a scalable approach to supporting people with long-term conditions [54,55].

Clinical effectiveness and practical implications

International examples of healthcare professional-led digital health models offer potential blueprints for healthcare system adaptation, particularly in contexts with multidisciplinary care development [49]. However, the transferability of these models depends on specific healthcare system characteristics, regulatory frameworks, and resource availability that vary significantly across settings. Digital health interventions demonstrated measurable improvements in daily functioning (60-meter improvement in 6-minute walk test), disease control (0.8% HbA1c reduction), and medication adherence (20% improvement), supporting a shift toward more holistic, patient-centred care models [56]. The adoption rates of 85-95% among older adults, when appropriate training and support were provided, directly challenge assumptions about digital exclusion among vulnerable populations. Sustained engagement remained above 80% at 6-month follow-up across all age groups, with older adults achieving clinical outcomes equal to or superior to younger users. This finding transforms our understanding of digital health implementation, showing that system-level support quality-not patient demographics-determines success [57]. For clinical practice, these results position healthcare professionals as facilitators of digital health adoption, leveraging core competencies in health education and individualised care planning.

Economic and Policy Implications

Economic evidence for digital health interventions remains limited within the chronic disease management literature. The Whole Systems Demonstrator study provides the most comprehensive cost-effectiveness analysis, demonstrating that telehealth interventions for patients with long-term conditions can achieve acceptable cost-effectiveness ratios [58]. However, these estimates rely heavily on healthcare utilisation reductions and may not fully capture implementation complexities or longterm sustainability costs. The documented reductions in healthcare utilisation from telemonitoring studies suggest potential for cost avoidance, though economic analyses remain sparse across the evidence base [59]. Systematic reviews of telemedicine economic evaluations indicate mixed findings, with positive outcomes dependent on intervention type, patient population, and healthcare system context [59]. Variations in how costs and outcomes are measured prevent meaningful comparisons between studies. For policymakers, digital health interventions demonstrate clinical effectiveness that may translate into economic value; however, investment decisions are constrained by a lack of robust economic evidence [60]. The scalability advantages of digital interventions remain theoretically promising, though successful implementation requires substantial investments in infrastructure, training, and ongoing support that are poorly quantified in existing research, [19]. The limited economic evidence represents a critical gap for informed healthcare policy decision-making. Future research priorities should include standardised economic evaluations that capture implementation costs, long-term sustainability expenses, and broader healthcare system impacts beyond direct cost savings [60].

Implementation and system factors

The implementation of digital health interventions requires attention to both technological and human factors, with evidence identifying specific critical success factors for e-health adoption [61]. The systematic review evidence demonstrates that both patients and providers initially experience technology-related challenges, but structured support systems can achieve improved confidence and adoption over time [62]. Digital literacy barriers represent a significant implementation challenge that can be addressed through adequate training and comprehensive infrastructure investment, including reliable connectivity [63-65]. This requires coordinated, system-wide implementation rather than isolated pilot projects, though the specific technical and organisational needs for successful integration require further study. Ensuring equitable access requires digital literacy training and reliable connectivity, supported by comprehensive infrastructure investment [65].

Irish healthcare context

Ireland’s healthcare challenges align with the chronic disease burden addressed in this review, with the Sláintecare Implementation Strategy recognising that chronic disease management represents a significant component of healthcare demand [50]. Ireland operates a mixed urban-rural health service that faces distinctive challenges, including geographic access barriers in remote and island communities, where residents may experience “feelings of isolation and social disconnection” [53]. The documented ability of digital interventions to support geographically dispersed populations directly addresses these access barriers relevant to Irish healthcare delivery, particularly given the HSE’s recognition that remote communities represent “hard to reach” populations requiring targeted health interventions [50]. Most supporting evidence, however, comes from countries with different healthcare financing models [53,54]. Ireland’s COVID-19 response demonstrated rapid healthcare innovation and “new technological improvements” implemented at pace, showing the system’s capacity for digital transformation. The pandemic also highlighted that “social isolation and loss of social links have a negative effect on the overall health and well-being” of vulnerable populations [50]. The HSE’s recent launch of Virtual Wards in 2024, enabling patients to receive hospital-level care at home through remote monitoring technology, demonstrates Ireland’s active commitment to expanding digital health capabilities for acute care delivery [19]. This builds upon established evidence from similar healthcare systems, where virtual wards have demonstrated patient satisfaction rates exceeding 99% and significant reductions in hospital-acquired infections compared to traditional inpatient care [55]. The evidence suggesting digital health acceptability among older populations with appropriate support provides direction for addressing these disparities [9], though implementation requires targeted resource allocation. The alignment with Sláintecare principles and HSE Healthy Ireland initiatives for addressing geographic health inequalities positions digital health as a tool for advancing universal healthcare goals [50], contingent on attention to accessibility and digital literacy support.

Strengths and limitations

Strength

The evidence from this systematic review supports the role of nurse practitioners in digital health implementation, from design through ongoing support. Nursing professionals offer opportunities to enhance care delivery through patient advocacy, holistic care, health promotion and the implementation of digital health technologies.

Limitations

Several limitations constrain the generalisability and policy utility of the current evidence highlighted in this systematic review. The predominance of studies from high-income countries (91%) with established digital infrastructure limits the applicability to resource-constrained settings. Short follow-up periods in 17% of studies leave questions about long-term sustainability unanswered. Medium-term studies (52%) provide the most robust evidence for sustained effectiveness. The critical economic evidence gap represents the most significant barrier to informed healthcare policy decision-making. Only 4% of studies provided a comprehensive economic evaluation. Future research priorities should include comprehensive cost-effectiveness analyses and cost benefit analysis that capture direct healthcare costs, implementation expenses, and broader societal impacts and return on investment. Research studies should take account of training costs, infrastructure requirements, and ongoing support needs with greater precision.

The non-representation of Irish healthcare within the European healthcare context highlights the need for locally relevant research. Although 65% European studies were identified, none include Irish data, a reflection of Ireland’s relatively recent entry into digital healthcare.

Research must account for specific system characteristics, regulatory frameworks, and cultural factors. The predominance of COPD studies (52%) compared to limited diabetes (4%) and asthma (4%) evidence represents another significant gap given the global burden of these conditions. Methodological challenges inherent in digital health research present ongoing concerns. The impossibility of participant blinding requires adapted quality assessment frameworks and more sophisticated study designs to strengthen causal inference.

Conclusion

This systematic review provides concrete evidence that digital health interventions represent a valuable component of chronic disease management. The documented clinical benefits and healthcare utilisation reductions support digital health inclusion in modern healthcare delivery. However, the strength of this support varies by condition and outcome. For nursing professionals, digital health offers opportunities to enhance care delivery through patient advocacy, holistic care, and health promotion. The evidence supports nursing’s role in digital health implementation, from design through ongoing support. This role requires adapting traditional competencies to include digital health education, remote patient assessment, and technology-supported care coordination.

For policymakers, the findings justify including digital health in chronic disease strategies. Evidence is strongest for COPD and heart failure management. However, economic value remains incompletely demonstrated. This limits confidence in large-scale investment decisions without additional economic evaluation. Implementation should proceed systematically. Healthcare systems should begin with conditions demonstrating the strongest evidence while building infrastructure for broader expansion. Success requires coordinated efforts across professional, technological, and policy domains. Particular attention must be given to equity and accessibility. System-level support quality, rather than patient demographics, determines success.

Acknowledgements and declarations

The authors thank the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland (RCSI) Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery PhD scholarship award and Health Service Executive (HSE) Ireland for institutional support, the Information Scientist at RCSI, Killian Walsh, for methodological guidance, and the international researchers whose primary studies enabled this evidence synthesis.

Funding

This systematic review was conducted as part of RCSI, Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery PhD scholarship award. No external funding was received.

Ethical approval and consent

As a systematic review of previously published literature, this study did not involve primary data collection from human participants. It therefore did not require Institutional Review Board approval or informed consent. The review protocol was prospectively registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO: CRD420250650909) before commencing the review to ensure methodological rigour and transparency. All included studies were peer-reviewed publications that had obtained appropriate ethical approvals as reported in their original manuscripts.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no financial conflicts of interest related to this systematic review. Antoinette Doherty (AD) is employed by the Health Service Executive (HSE) Ireland, an organisation that may benefit from digital health implementation. However, this affiliation did not influence the objective design, conduct, analysis, or reporting of this systematic review. All authors maintained scientific independence throughout the research process. No commercial entities or organisations with vested interests in digital health technologies provided funding or influenced the review methodology or findings.

Author contributions

Antoinette Doherty (AD): Conceptualisation, methodology, literature search execution, study selection, data extraction, quality assessment, data synthesis, original draft preparation, and manuscript writing.

Professor Mary Lynch (ML): Methodology oversight, protocol development, supervision, critical review, and final manuscript approval.

Dr. Llinos Haf Spencer (LHS): Independent study selection, data verification, methodological consultation, critical review, and final manuscript approval. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding statement

This systematic review was conducted as part of a PhD scholarship awarded by the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland (RCSI), Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery. No external funding was received for this research. The funding body had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or manuscript preparation.

Data availability statement

All data supporting the findings of this systematic review are available within the article and its supplementary materials. The systematic review protocol is publicly available through PROSPERO registration CRD420250650909 at https://www.crd. york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/. Raw data extraction forms and quality assessment documentation are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- World Health Organisation. Noncommunicable diseases progress monitor 2025.

- Holman H (2020) The relation of the chronic disease epidemic to the health care crisis. Acad Med 95: 812-818.

- Health Service Executive (2024) ICP for Prevention and Management of Chronic Disease.

- Hayes TON, Gillian S (2020) American Action Forum. Chronic Disease in the United States: A Worsening Health and Economic Crisis.

- Lane A, Clarke V (2021) Report on the Findings of the First National Evaluation of the use of Video Enabled Health Care in Ireland. Dublin: HSE National Telehealth Steering Committee.

- Shi R, Messner F, Gehring M, Ebner-Priemer U, Zeevi D (2021) Digital health and wearable technologies for monitoring and management of cancer patients outside the clinic. JMIR Cancer 7: e30550.

- Ma Y, Zhao C, Zhao Y (2022) Telemedicine application in patients with chronic disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 22: 105.

- Taylor M, Thomas E, Snowsill C, Smith A, Caffery L (2021) Does remote patient monitoring reduce acute care use? A systematic review. BMJ Open 11: e040232.

- KPMG Ireland (2024) Empowering Ireland’s healthcare future.

- Tandan M, Twomey B, Twomey L, Egan M, Bury G (2022) National Chronic Disease Management Programmes in Irish General PracticePreparedness and Challenges. J Pers Med 12: 1157.

- Health Service Executive. HSE Urgent and Emergency Care Operational Plan 2024.

- McHale M (2025) More than 120,000 patients were treated on trolleys in 2024.

- Health Service Executive (2024) Telehealth Roadmap 2024-2027.

- Healthcare transformation challenges and opportunities in Ireland in 2025.

- NHS Health Call (2024) NHS Virtual Wards: What you need to know before setting one up.

- Norman G, Bennett P, Vardy ERLC (2023) Virtual wards: a rapid evidence synthesis and implications for the care of older people. Age Ageing 52: afac319.

- Wells E, Gatfield T (2024) Virtual wards: benefits, challenges and required skills. Nurs Times 120: 10.

- Conroy S, Doswell G, Husk J (2023) Virtual wards: a rapid evidence synthesis and implications for the care of older people. Age Ageing 52: afac319.

- Health Service Executive (2024) National Virtual Ward Programme.

- Higgins J, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, et al. (2024) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.

- Page M, McKenzie J, Bossuyt P, Bourton I, Hoffmann T, et al. (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372: n71.

- Covidence (2025) Covidence - Better systematic review management.

- Joanna Briggs Institute (2020) JBI Critical Appraisal Tools.

- Arnaert A, Ahmad H, Mohamed S, Hudson E, Craciunas S, et al. (2022) Experiences of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease receiving integrated telehealth nursing services during COVID-19 lockdown. BMC Nurs 21: 1-13.

- Vestergaard AS, Hansen L, Sørensen SS, Jensen MB, Ehlers LH (2020) Is telehealth care for heart failure patients cost-effective? An economic evaluation alongside the Danish Telecare North heart failure trial. BMJ Open 10: e031670.

- Messori A, Romeo M, Fadda V, Collini F, Tripoli S (2024) Costs and benefits in patients with NYHA class III heart failure treated with Cardio MEMS in Italy. Glob Reg Health Techno Assess. 11: 105-107.

- Fredman A, Tran M, Boyle K, Goldberg E, Onufer J (2018) Bundled Hospital-at-Home and Transitional Care Program Is Associated with Reduced Rate of Hospital Readmission. J Clin Outcomes Manag 25: 448-450.

- Schäfer J, Carvalho L, da Fonseca Miranda N, Vitiello I, Paiva D, et al. (2015) Use of audiovisual media for education and self-management of patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease - COPD. Fisioter Mov 28: 97-106.

- Koff P, Min S, Diaz D, Freitag T, James S, et al. (2020) Impact of proactive integrated care on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chronic Obst Plum Dis 8: 90-99.

- Vianello A, Fusello M, Gubian L, Rinaldo C, Dario C, et al. (2016) Home telemonitoring for patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Plum Med 16: 157.

- Lopez-Villegas A, Catalan-Matamoros D, Peiro S, Lappegard KT, Lopez-Liria R (2020) Costutility analysis of telemonitoring versus conventional hospital-based follow-up of patients with pacemakers. The NORDLAND randomised clinical trial. Andò G, editor. PLOS ONE 2020 15: e0226188.

- Kamei T, Yamamoto Y, Kanamori T, Nakayama Y, Porter SE (2018) Detection of early‐stage changes in people with chronic diseases: A tele home monitoring‐based telenursing feasibility study. Nurs Health Sci 20: 313-322.

- Garcia-Carretero R, Vazquez-Gomez O, Luna-Heredia E, VargasRojo B, Fernandez-Cotarelo MJ, (2022) Management of COPD in a Hospital-at-Home Setting at a Peripheral Spanish Hospital: 8-Year Experience. Home Health Care Manag Pract 34: 246-251.

- Timmermans I, Meine M, Szendey I, Aring J, Romero Roldán J, Van Erven L, et al. Remote monitoring of implantable cardioverter defibrillators: Patient experiences and preferences for follow‐up. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 42: 120-129.

- Codina P, Vicente Gómez JÁ, Hernández Guillemet G, Ricou Ríos L, Carrete A, et al. Assessing the impact of haemodynamic monitoring with Cardio MEMS on heart failure patients: a cost–benefit analysis. ESC Heart Fail 11: 1955-1962.

- Bernocchi P, Vitacca M, La Rovere MT, Volterrani M, Galli T, et al. (2018) Home-based telerehabilitation in older patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and heart failure: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing 47: 82-88.

- Kardas P, Lewandowski K, Bromuri S (2016) Type 2 Diabetes Patients Benefit from the COMODITY12 mHealth System: Results of a Randomised Trial. J Med Syst 40: 259.

- Bogacz K, Szczegielniak A, Czekaj Ł, Jarynowski A, Kitłowski R, et al. (2024) Assessment of rehabilitation effectiveness in patients with COPD as part of the project ‘Pulmo Rehab – Access to healthcare services through a personalised care system for patients with COPD, including remote monitoring and tele-rehabilitation based on Artificial Intelligence methods’. Kassolik K, editor. Fizjoterapia Pol 24: 6-11.

- Hamad GA, Crooks M, Morice AH (2016) The value of telehealth in the early detection of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations: A prospective observational study. Health Informatics J 22: 406-413.

- O’Leary J, Lannutti K, Tollefsen W, Duffy E, Tracy J (2021) Mobile Integrated Health: Reducing Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Hospitalisations Through Novel Outpatient Care Initiatives. J Clin Outcomes Manag 28: 232-240.

- Korsbakke Emtekær HL, Ehlers L, Hejlesen O (2016) Interaction between functional health literacy and tele homecare: Short-term effects from a randomised trial. Nurs Health Sci 18: 328-333.

- Sten-Gahmberg S, Pedersen K, Harsheim IG, Løyland HI, Snilsberg Ø, et al. (2024) Pragmatic randomised controlled trial comparing a complex telemedicine-based intervention with usual care in patients with chronic conditions. Eur J Health Econ 25: 1275-1289.

- Poureslami I, Shum J, Lester RT, Tavakoli H, Dorscheid DR, et al. (2018) A pilot randomised controlled trial on the impact of text messaging check-ins and a web-based asthma action plan versus a written action plan on asthma exacerbations. J Asthma 56: 897-909.

- Barken TL, Thygesen E, Söderhamn U (2018) Unlocking the limitations: Living with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and receiving care through telemedicineA phenomenological study. J Clin Nurs 27: 132-142.

- Mathar H, Fastholm P, Sandholm N (2015) A qualitative study of TeleVideo consultations for COPD patients. Br J Nurs 24: 205-209.

- Cerdán De Las Heras J, Tulppo M, Kiviniemi AM, Hilberg O, Løkke A, et al. (2022) Augmented reality glasses as a new tele-rehabilitation tool for home use: patients perception and expectations. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol 17: 480-486.

- Cartwright M, Hirani S, Rixon L, Beynon M, Doll H, et al. (2013) Effect of telehealth on quality of life and psychological outcomes over 12 months (Whole Systems Demonstrator telehealth questionnaire study). BMJ 346: 653.

- Department of Health Ireland (2021) Sláintecare Implementation Strategy & Action Plan 2021-2023.

- Greenhalgh T, Wherton J, Papoutsi C, Lynch J, Hughes G, et al. (2017) Beyond adoption: a new framework for theorising and evaluating Nonadoption, abandonment, and challenges to the scale-up, spread, and sustainability of health and care technologies. J Med Internet Res 19: e8775.

- Health Service Executive (2024) Healthy Islands Initiative: Supporting Health and Wellbeing in Remote Communities.

- Henderson C, Knapp M, Fernández J, Beecham J, Hirani SP, et al. (2013) Cost effectiveness of telehealth for patients with long term conditions (Whole Systems Demonstrator telehealth questionnaire study). BMJ 346: f1035.

- Koehler F, Winkler S, Schieber M, Sechtem U, Stangl K, et al. (2011) Impact of remote telemedical management on mortality and hospitalisations in ambulatory patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation 123: 1873-1880.

- Lenferink A, Brusse-Keizer M, van der Valk P, Frith PA, Zwerink M, et al. (2017) Self-management interventions including action plans for exacerbations versus usual care in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 8: CD011682.

- May C, Cummings A, Girling M, Bracher M, Mair FS, et al. (2018) Using Normalisation Process Theory in feasibility studies and process evaluations of complex healthcare interventions: a systematic review. Implement Sci 13: 80.

- NHS England & GIRFT (2023) Making the most of virtual wards, including Hospital at Home: Practical guidance for clinicians to maximise use of virtual wards for the benefit of patients.

- Pinnock H, Hanley J, McCloughan L, Todd A, Krishan A, et al. (2013) Effectiveness of telemonitoring integrated into existing clinical services on hospital admission for exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: researcher blind, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. BMJ 347: 6070.

- Ross J, Stevenson F, Lau R, Murray E (2016) Factors that influence the implementation of e-health: a systematic review of systematic reviews. Implement Sci 11: 146.

- Steventon A, Bardsley M, Billings J, Doll H, Tuckey E, et al. (2014) Effect of telehealth on glycaemic control: analysis of patients with type 2 diabetes in the Whole Systems Demonstrator cluster randomised trial. BMC Health Serv Res 12: 312.

- de la Torre-Díez I, López-Coronado M, Vaca C, Aguado JS, Castro CD (2015) Cost-utility and cost-effectiveness studies of telemedicine, electronic, and mobile health systems in the literature: a systematic review. Telemid E-Health 21: 79-85.

- Gentili A, Failla G, Melnyk A, Puleo V, Di Tanna GL, et al. (2022) The cost-effectiveness of digital health interventions: A systematic review of the literature.

- Berardi C, Antonini M, Jordan Z, Wechtler H, Paolucci F, et al. (2024) Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of digital technologies in mental health systems: a qualitative systematic review to inform a policy framework.

- Alotaibi N, Wilson CB, Traynor M (2025) Enhancing digital readiness and capability in healthcare: a systematic review of interventions, barriers, and facilitators.

- Pong C, Tseng RMWW, Tham YC, Lum E (2024) Current Implementation of Digital Health in Chronic Disease Management: Scoping Review.

- Geracitano J, Barron L, McSwain D, Khairat S (2024) How is digital health suitability measured for communities? A systematic review. Digit Health 10: 20552076241288316.

- Alotaibi N, Wilson CB, Traynor M (2025) Enhancing digital readiness and capability in healthcare: a systematic review of interventions, barriers, and facilitators. BMC Health Serv Res 25: 500.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.