Curative Electrochemotherapy for Basal Cell Carcinoma Is Superior to Palliative in Elderly Patients

by Robert M. Eisele*

Surgical Center Oranienburg, Germany.

*Corresponding author: Eisele RM, Surgical Center Oranienburg, Oranienburg, Germany.

Received Date: 17 June, 2025

Accepted Date: 23 June, 2025

Published Date: 26 June, 2025.

Citation: Eisele RM (2025) Curative Electrochemotherapy for Basal Cell Carcinoma Is Superior to Palliative in Elderly Patients. J Oncol Res Ther 10: 10291. https://doi.org/10.29011/2574-710X.10291.

Abstract

Background: Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most prevalent skin tumor worldwide. Electrochemotherapy (ECT) as an interventional treatment for BCC has been shown to be effective and is regarded an alternative treatment option if surgery is not feasible. Objectives: Our aim was to treat patients with curative (c) and palliative (p) intention and to compare results in terms of treatment response, survival and applicability. Methods: Complete response was intended in c, not in p. Day-surgical procedures were performed under sterile conditions with general or local anesthesia and heeded the published recommendations of the interdisciplinary pan-European expert panel. Bleomycin was intralesionally injected; we used a CE-certified generator with a four-pronged applicator and applied RECIST criteria. Follow-up examinations were scheduled after 4 weeks, 3 months and annually thereafter. Results: The palliative group (n=2) was significantly older than c (n=5), 95 +/- 4.2 vs. 78 +/- 3.1 years (p<0.0001, t-test). Survival was significantly shorter in p with 2.5 vs. 14.8 months in c (p<0.05, logRank-test). Complete (CR) or partial response (PR) was 0 % in p and 60 % (CR) or 40 % (PR) in c, respectively (p=0.0001, chi2-test). The bleomycin dosage significantly differed (p: 5250 +/-3182 vs. c: 1770 +/- 1839 I.U., p<0.05, t-test) indicating larger and more extended disease in p. In p, ECT was performed under local anesthesia, and in c, general (n=3) and local (n=2) anesthesia was performed (p=0.33, chi2-test). Conclusions: ECT for BCC is safe and applicable. In p, no response at all was recorded, whereas c was successfully treated with predominantly complete response.

Keywords: Electroporation; electrochemotherapy; basal cell carcinoma.

Background

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is one of the most prevalent skin tumors worldwide. Incidence raises with increasing age. In Germany, the incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer increased significantly from 43.1 cases per 100’000 inhabitants in 1998 to 105.2/100’000 in 2010 [1]. The gold standard in the treatment of BCC is surgery [2]. The slow growth rate and the comparably late – if ever – occurrence of metastases implies the consideration of less invasive treatment modalities in older patients, recurrencies and second or last line treatments.

Electrochemotherapy (ECT) is an interventional treatment for BCC with promising results [3,4]. In the recently updated European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline for diagnosis and treatment of basal cell carcinoma, ECT is mentioned as a feasible treatment option for “locally advanced or recurrent BCC when standard treatments are not feasible, with good tumor control and functional results without systemic adverse events” [5].

Although the recommendation implicates a preponderantly palliative purpose, good results with regard to tumor control and preserved function seem to point at an optional application of ECT also with curative intention. Our aim was to offer ECT to our BCC patients and compare results obtained in palliative patients to curative cases. We decided to apply the revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) [6] to evaluate treatment success.

ECT can be performed under general anesthesia or local anesthesia with or without mild sedation [7]. Bleomycin can be administered intralesionally [8] or systemically. Application of ECT for BCC under local anesthesia with intralesional injection of Bleomycin makes it attractive to treat patients with comorbidities, frailty and advanced age in a day-surgical unit.

Patients and Methods

Indications were histologically confirmed BCC if surgery was declined or infeasible. Allocation to palliative (p) or curative (c) group was dependent on the intention to achieve complete response in terms of local tumor control. Exclusion criteria were anteceding treatment with Bleomycin, presence of fibrosing lung disease as per preoperative X-ray assessment, known hypersensitivity or incorrected bleeding disorder. No examinations except for a general clinical exploration were felt mandatory to rule out metastatic disease or extraanatomic tumor spread. Informed consent was obligatory.

The use of general or local anesthesia was chosen according to patient preferences, among others influenced by reimbursement issues. Day-surgical procedures were performed under sterile conditions and heeded the published recommendations of the interdisciplinary pan-European expert panel [9]. The required dose of Bleomycin was calculated according to the guideline of the interdisciplinary pan-European expert panel which was published 2018 [9]. In brief, the volume of the lesion was calculated as ab2π/6, where b is the smaller diameter of the tumor, and a the longer. 1000 I.U. Bleomycin (Bleomycin Baxter 15000 I.U., Baxter AG, 8152 Opfikon, Switzerland) per cm3 tumor volume was injected intralesionally 30 sec. prior to the start of the delivery of electric pulses.

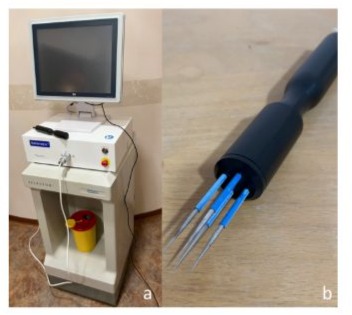

The generator in use was the CE-certified SENNEX® system (Bionmed Technologies GmbH, 66123 Saarbrücken, Germany) [fig. 1a]. It is capable of delivering 8 successive pulses each with 80 µs duration. Among the two available hand pieces, we chose the four prong model [figure 1b]. The reliable field strength is 1000 V/cm.

Figure 1: Setup of equipment. a. Sennex® system consisting in monitor (above), generator (beneath) and tray. b. Four prong applicator with electrodes in an unsterile setting.

Postoperative follow-up included clinical examinations and photographic imaging within one week, after four weeks, after 3 months, after one year and annually thereafter. After four weeks, another chest X-ray was performed. Response was recorded according to the revised Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST criteria) version 1.1 discerning four categories of treatment response:

Complete Response (CR) – disappearance of the treated lesion

Partial Response (PR) – at least a 30 % decrease in the diameter of the lesion

Stable Disease (SD) – neither sufficient shrinkage to qualify for PR nor sufficient increase to qualify for PD

Progressive Disease (PD) – at least a 20 % increase in the diameter of the lesion

In case of recurrence, initial CR was downgraded to PR and rescue surgery was offered.

Statistical analysis encompassed data description with mean +/- standard deviation in case of standard normal distribution, and median and range in case of non-standard normal distribution. Comparisons would be performed using Student’s t-test, if parametric data were analyzed, and Chi-square test, if categorical data were present. Usually, the p values are presented as raw data. Statistical significance was considered robust in p values below 0.05, and strong in p values below 0.01. No correction for β error was intended.

Results

The patients treated within the frame of this retrospective observational study are displayed in table 1. The observational groups p and c differed significantly in terms of age and Bleomycin dosage, and were similar with regard to gender, use of general vs. local anesthesia and application of the chemotherapeutic agent. The palliative group (n=2) was significantly older than c (n=5) with 95 +/- 4.2 vs. 78 +/- 3.1 years (p<0.0001, t-test). In p, larger and more extended disease was treated as indicated by significantly higher Bleomycin dosage of 5250 +/-3182 I.U. vs. 1770 +/- 1839 I.U. in c (p<0.05, t-test). In p, ECT was performed under local anesthesia, and in c, general (n=3) and local (n=2) anesthesia was performed (p=0.33, chi2-test).

Table 1: Patients treated within the frame of the study. |

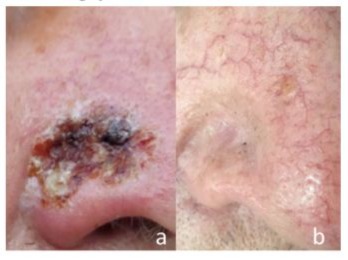

Histological confirmation was felt mandatory prior to the application of a chemotherapeutic agent like Bleomycin. In p, the diagnosis was known for years, yet clinical signs indicated neither remote tumor spread nor systemic disease in any case. The histological and clinical subtype was ulcerative in both palliative cases (fig. 2), one of these has already been surgically removed four years earlier. In c, three of the five patients were treated for recurrent BCC. The histological subtype was partly basosquamous, partly morpheaform in one, partly micronodular, partly morpheaform (approximately 30 %) in another and superficially spreading in the remaining case. Time span from initial treatment to ECT ranged from 1 to 2 years. In the two primary cases, histological examination was obtained with a biopsy sampled immediately prior to ECT. The findings were ulcerative solid nodular and morpheaform in these cases.

Figure 2: Treatment of a palliative case. a. Pre-procedural close-up. b. Glimpse of the operating theatre with ongoing procedure.

Initial success (CR or PR) was recorded if substantial shrinkage of the target lesions was documented within the first one to three months following the ECT. Complete disappearance of the lesion was determined CR. In case initial success followed by PD, surgery was offered in c, whereas persistent or recurring disease was left untreated in p. Such a resection was performed in two curative patients. In both cases, upfront surgical resection would have been difficult unless impossible; ECT enabled surgery by down-sizing in one case (recurrence-free period of 17 months) and in the other case by treating parts of the tumor with contact to the eye; the recurrence occurred 5 months later at the site of the precursing biopsy. In these two cases, the initial success was retrospectively determined PR. After R0 resection, secondary success was achieved in both cases.

Survival was significantly shorter in p with 2.5 vs. 14.8 months in c (p<0.05, logRank-test). Complete (CR) or partial response (PR) was 0 % in p and 60 % (CR) or 40 % (PR) in c, respectively (p=0.0001, chi2-test). Initial success was therefore recorded in 60 % and secondary success in 40 % in c. No success at all could be found in p. Eventually, all c patients are free of disease at the end of the follow-up period with four out of five still alive. In contrast, all palliative patients deceased within the first three months following the procedure. In this period, we could neither achieve any decrease in the amount of required wound dressing material, in the frequency of wound nurse visits nor in odour nuisance.

In terms of toxicity, no fibrosing lung disease was found in the follow-up examinations. The treatment was generally well tolerated. The local reactions at the skin to the application of Bleomycin was characterized by temporary reddish swelling, secretion and necrosis, which rapidly relieved within a couple of days (fig. 3). However, three of seven patients died early after the procedure (after 2, 3 and 5 months, respectively). The relatives denied autopsies in each case. Thus, the reasons for death in our patients remain largely unknown.

Figure 3: Recurrent basal cell carcinoma at the nose. a. Early after the intervention (four weeks). b. Eventual result (three months).

Discussion

The first cases reported herein have been treated in 2020. Palliative ECT was performed in two patients >90 years old with ulcerative and extensive BCC. Results in terms of local control and survival were disappointing. This resembles the findings published later by Sersa et al., who reported in 2021 on 61 patients found in a cohort analysis from the International Network for Sharing Practice in ECT (InspECT) registry with an age of 90 years and more [10]. He concludes, that “tumours with pre-existing extensive ulceration do not benefit from treatment”. In addition, Campana et al. found significantly worse outcome in ulcerative disease with 31 % local control rate vs. 69 % in absence of ulceration (p=0.001) and 52 % recurrence vs. 12 % (p> 0.001) [4]. In contrast, occasionally published case reports indicate successful treatment of ulcerative BCC with ECT, but not in older patients [11].

Jamsek et al. [12] treated 28 BCC patients with a median age of 81 years with ECT, 16 of them with a standard dose of intravenous Bleomycin, 12 with a reduced dosage (10000 instead of 15000 I.U.), both exceeding the Bleomycin doses used in our own treatments. However, we applied intralesional chemotherapy, which makes it difficult to compare our results to others obtained with ECT after systemic administration. Jamsek and colleagues found no statistically significant difference regarding outcome and local tumor control with a recurrence rate of 39 % per tumor after a median of 18.5 months in the study population and 15.4 % after 7 months in the control group. The authors concluded that despite these results, ECT for BCC with reduced dose of Bleomycin is feasible and indicated in advanced aged patients with comorbidities, where overall life expectancy is poor.

Life expectancy of palliative and curative patients is difficult to compare. The probability to live up to the age of 90 is higher for 80 years old individuals compared to the average population. Whereas the life expectancy for newborn male Germans is currently 78,2 years, it increases to 87,9 years for an 80 year old individual, to 93,5 years for a 90 year old one and even to 101,7 years if he or she is already 100 years old [13]. BCC is an unlikely reason for death, which means that the benefit from a treatment of BCC in older patients might not be regarded less than in younger patients. However, in our series, obviously neither local control leading to a potential higher quality of life, nor survival were increased by ECT in the palliative patients.

ECT for BCC is infrequently reported in the literature. The treatment is nevertheless recommended in the most recent update of the European guidelines [5]. Most of the available literature consists in case series or case reports [14,15]. The largest series is the InspECT report revealing >80 % complete response after one treatment [16]. 300 patients with 587 tumours were evaluated. Only 39 treatments (13 %) were considered palliative. The combined partial and complete response rate was with 96 % similar to the one in our observations, at least in group c.

Clover et al. conducted a randomized controlled trial comparing ECT to surgery for BCC [17]. They found insignificant differences in local tumor control with 97,5 % in the surgery group and 87,5 % in the ECT group (p=0.33). In another study, Lyons, Kennedy and Clover demonstrated superiority of ECT for BCC in visible localizations in the face in terms of post-therapeutic facial appearance, whereas simultaneously, worriness about cancer as well as clinical outcome were equivalent in both groups [18]. Both findings indicate that ECT might be as effective as surgical excision even in curative intention for the treatment of BCC. We drew a similar conclusion out of the presented data of our experience.

Conclusions

This report suffers from various shortcomings:

First of all, the small number of patients impede a sound statistical analysis resulting in robust and significant results. Even though, the statistically significant data obtained are remarkable and generally confirm results found in the literature.

Survival might be inappropriate in the comparison of treatment modalities for BCC as the prevalence of basal cell carcinoma is increasing with age albeit rarely lethal.

The palliative patients were significantly older than the curative. A Kaplan-Meier estimation could correct for this bias, but rendered infeasible due to the small number of cases

Confounding factors like experience of the physician and learning curve are not controlled in this retrospective observational study.

The absence of a control group makes it difficult to estimate a potential benefit of a palliative treatment, the obvious bias in comparing a palliative to a curative intervention left aside.

On the other hand, these are real world data observed on a daily practical work with patients under conditions far away from laboratories or trials. We draw the conclusion that ECT with a curative intention may without hesitation be recommended according to the European guideline for BCC in selected cases, whereas palliative ECT remains a last line option reserved for rare occasions and proved to be unsatisfying in case of extensive preexisting ulcerative BCC in patients with very advanced age.

References

- Rudolph C, Schnoor M, Eisemann N, et al. (2015) Incidence trends of nonmelanoma skin cancer in Germany from 1998 to 2010. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 13:788-97.

- Marzuka AG, Book SE (2015) Basal cell carcinoma: Pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, histopathology and management. Yale J Biol Med 88:167-79.

- Bertino G, Sersa G, deTerlizzi F, Occhini A, Plaschke CC, et al. (2016) European Research on Electrochemotherapy in Head and Neck Cancer (EURECA) project: Results of the treatment of skin cancer. Eur J Cancer 63:41-52.

- Campana LG, Marconato R, Valpione S, Galuppo S, Alaibac M, et al. (2017) Basal cell carcinoma: 10-year experience with electrochemotherapy. J Transl Med 15:122.

- Peris K, Fargnoli MC, Kaufmann R, Arenberger P, Bastholt L, et al. (2023) European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline for diagnosis and treatment of basal cell carcinoma – update 2023. Eur J Cancer 192:113254.

- Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz H, Sargent D, et al. (2009) New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 45:228-47.

- Gyurova MS, Stancheva MZ, Arnaudova MN, Yankova RK (2006) Intralesional Bleomycin al alternative therapy in the treatment of multiple basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol online J 12:25.

- Benedik J, Ogorevc B, Kranjc Brezar S, Cemazar M, Sersa G, et al. (2022) Comparison of general anesthesia and continuous intravenous sedation for electrochemotherapy of head and neck skin lesions. Front Oncol 12:1011721.

- Gehl J, Sersa G, Wichmann Matthiessen L, Muir T, Soden D, et al. (2018) Updated standard operating procedures for electrochemotherapy of cutaneous tumours and skin metastases. Acta Oncologica 57:874-82.

- Sersa G, Mascherini M, diPrata C, Odili J, deTerlizzi F, et al. (2021) Outcomes of older adults aged 90 and over with cutaneous malignancies after electrochemotherapy with bleomycin: A matched cohort analysis from the InspECT registry. Eur J Surg Oncol 47:90212.

- Richetta AG, Curatolo P, d’Epiro S, Mancini M, Mattozzi C, et al. (2011) Efficacy of electrochemotherapy in ulcerated basal cell carcinoma. Clin Ter 162:443-5.

- Jamsek C, Sersa G, Bosnjak M, Groselj A (2020) Long term response of electrochemotherapy with reduced dose of bleomycin in elderly patients with head and neck non-melanoma skin cancer. Radiol Oncol 54:79-85.

- Statistisches Bundesamt 2024: Statistischer Bericht, Sterbetafeln 2021/2023; Pressemitteilung Nr. 320 vom 21. August 2024 Lebenserwartung 2023 wieder angestiegen, Rückgänge der Pandemiejahre 2020 bis 2022 teilweise aufgeholt“, accessed on Nov 2nd 2024.

- Kis EG, Baltás E, Ócsai H, Vass A, Németh IB, et al. (2019) Electrochemotherapy in the treatment of locally advanced or recurrent eyelid-periocular basal cell carcinomas. Sci Rep 9:4285..

- Ruggeri R, Maurichi A, Tinti MC, Cadenelli P, Patuzzo R, et al. (2015) Electrochemotherapy: A good idea in recurrent basal cell carcinoma treatment. Melanoma Manag 2:27–31.

- Bertino G, Muir T, Odili J, Groselj A, Marconato R, et al. (2022) Treatment of basal cell carcinoma with Electrochemotherapy: Insights from the InspECT registry (2008-2019). Curr Oncol 29 :5324-37.

- Clover AJP, Salwa SP, Bourke MG, McKiernan J, Forde PF, et al. (2020) Electrochemotherapy for the treatment of primary basal cell carcinoma - A randomised control trial comparing electrochemotherapy and surgery with five-year follow-up. Eur J Surg Oncol 46:847–54.

- Lyons P, Kennedy A, Clover AJP (2021) Electrochemotherapy and basal cell carcinomas: First-time appraisal of the efficacy of electrochemotherapy on survivorship using FACE-Q. JPRAS Open 27:119-28.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.