Cryotherapy in the Treatment of Neuroma in Male Wistar Rats

by Bernardo Barreto Corrêa1*, Marcela Fernandes1, Maria Tereza de Seixa Alves2, Sandra Gomes Valente3, Luis Renato Nakachima1, João Carlos Belloti1

1Department of Hand and Upper Limb Surgery, Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology, Universidade Federal de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

2Department of Pathology, Universidade Federal de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

3Department of Biology, Universidade Federal de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

*Corresponding author: Bernardo Barreto Corrêa, Department of Hand and Upper Limb Surgery, Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology, Universidade Federal de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

Received Date: 18 October 2024

Accepted Date: 23 October 2024

Published Date: 26 October 2024

Citation: Corrêa BB, Fernandes M, Alves MTDS, Valente SG, Nakachima LR, et al. (2024) Use of Cryotherapy in the Treatment of Neuroma in Male Wistar Rats Cryotherapy in the Treatment of Neuroma in Male Wistar Rats. J Surg 9: 11164 https://doi.org/10.29011/2575-9760.11164

Abstract

Background: Post-traumatic neuroma results from the proliferation of neural tissue following nerve bundle damage, leading to pain and disability. Cryotherapy is a growing technique for chronic pain treatment. To better understand its effects on post-traumatic neuroma, we explored its use in this study.

Materials and Methods: Twenty-five male Wistar rats were divided into three groups: Sham (n=5), Control (n=10), and Cryotherapy (n=10). In the latter two groups, a distal lateral thigh incision was made to identify the tibial nerve, followed by transection and fixation below the skin. Sixty days post-transection, the Cryotherapy Group was treated at the neuroma site. Behavioral tests assessed tissue sensitivity to mechanical stimulation after surgery. After 120 days, all rats were euthanized for histological vessel count and immunohistochemical analysis of Schwann cells using SOX10 protein antigen.

Results: Initial behavioral tests showed no statistical difference between the Control and Cryotherapy Groups. After 120 days, the Cryotherapy Group had better outcomes compared to the Control. Vessel count showed a statistical difference between the Sham and Cryotherapy Groups versus the Control. No significant difference was found between the Sham and Cryotherapy Groups. The Cryotherapy Group exhibited reduced Schwann cell mean and variability compared to the Control, though not as low as the Sham.

Conclusion: Cryotherapy was effective in treating neuroma in rats.

Introduction

Post-traumatic neuroma is the result of a proliferation of neural tissue after damage or transection of a nerve bundle [1]. After a nerve injury, the proximal portion seeks to regenerate itself and reestablish the innervation of the distal segment through axon growth inside the tubules of proliferative Schwann cells [1-3]. When there is no well-structured tissue, the regenerating elements still initiate the reinnervation process, resulting in the disorganized growth of a tumor-like mass at the site of the injury, which is called a neuroma [1,4-6]. This process can be observed 28 days after the nerve injury. Histologically, it consists of Schwann cells, fibroblasts, irregular bundles of axons and even inflammatory factors [7]. After the nerve transection, a neuroma may develop due to misdirected proliferation of the nerve stump [8]. Irregular endoneural architecture and prevalence of fibrous scar tissue characterize the main histopathological finding in neuromas. The clinical picture can be painful, leading to severe functional and physiological patient disability. In the past, several techniques have been described with the aim of preventing neuroma formation [9-12] and different factors have been attributed as influencing the extent of its development. Mackinnon et al. [13] postulated that denervation overlying the skin may be a pathophysiological factor in neuroma formation. However, to date, none of the studied methods have managed to completely prevent this formation. When visually identified or detectable by palpation, neuromas can be surgically removed or reduced in size by electrocoagulation or freezing [14,15]. In other cases, the neuroma can be redirected intraoperatively to the bone or muscle [16-19]. Several techniques are described in the literature for the management of neuroma pain, such as drug therapy with the use of opioids, anticonvulsants, antidepressants, local anesthetics and calcitonin, the latter used to inhibit pain signaling pathways [20]. Cryotherapy is a technique that has been gaining acceptance for the treatment of chronic pain, especially in cases where the patient refuses pharmacological methods, due to their high rates of complications and side effects, or in cases where previous treatments have failed [21].

It has been used in several indications such as chronic pain syndromes, including phantom limb, painful neuromas, painful superficial scars, chronic low back pain with radiculopathy, and in cases of pain caused by neoplastic diseases [21,22]. Also known as cryoneuroablation or cryoneurolysis, this intervention technique has been described as an alternative to phenol injections in the treatment of post-traumatic neuromas. The application of an extremely low temperature to the nerve creates a conduction block similar to the effect of local anesthetics, and the effect of improving chronic pain occurs through damage to the vasa nervorum, which will cause endoneural edema and Wallerian degeneration of the nerve. In short, freezing interrupts nerve conduction, leaving the Schwann cells intact, which allows the nerve to regenerate and restore its function [22]. Since this technique is yet to be established and the fact that it has not been widely studied in the literature, we chose to use it in this study to gain a better understanding of its use and effects on the treatment of post-traumatic neuroma. This study aimed to evaluate the use of cryotherapy in the treatment of neuromas caused by traumatic injuries in rats, analyzing the animals’ behavioral changes by assessing tissue sensitivity to mechanical stimulation throughout the study period, as well as histological changes.

Materials and Methods

Twenty-five (25) male Wistar rats, aged 7-8 weeks, weighing between 250 and 280g, were used in the study. They were kept in a vivarium under controlled conditions with a light/dark cycle (12/12 h), temperature of 21± 2°C, and free access to water and food throughout the experiment. If changes were observed after the procedures, such as abnormal ocular and nasal discharge, abnormal hair loss, lethargic or aggressive behavior, lack of grooming, abdominal distension, or weight loss, the animal was removed from the study and euthanized. The animals, from the University of São Judas, were kept in the Collective Animal Facility (CEUA/ UNIFESP, N. 4) on the 8th floor of Research Building I (Horácio Kneese de Mello) until they were euthanized. The surgical procedures were performed in the Microsurgery Laboratory of the Hand and Upper Limb Surgery Discipline of the Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology, and the nerve histological analysis was performed in the Department of Pathology at UNIFESP. The rats were divided into three groups: experimental group (n=10), control group (n=10) and sham group (n=5).

Surgical Procedure

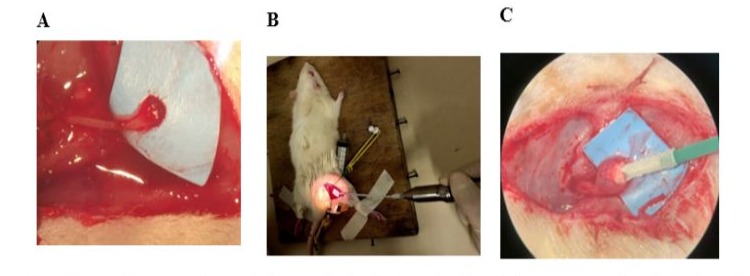

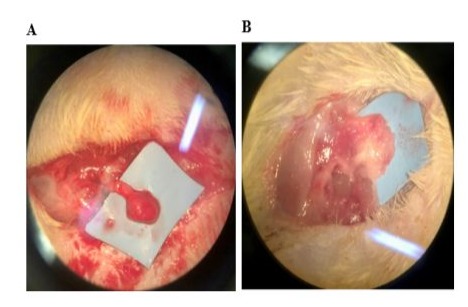

The animals were pre-anesthetized with fentanyl (0.16 mg/kg - sc) followed by anesthesia with a solution consisting of meloxicam (2 mg/kg) + tramadol (10 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) + ketamine (90 mg/kg) intraperitoneally, 30 minutes before the surgical procedure, according to the guide for anesthesia and analgesia in laboratory animals [23]. To maintain the animal in the anesthetic plane, we used 3% isoflurane by inhalation. After being anesthetized, the animal was placed in dorsal decubitus, on a board, with the limbs fixed with masking tape and the surgical site was shaved followed by degerming with a 0.5% alcoholic chlorhexidine solution. In both the Cryotherapy Group (n=10) and the Control Group (n=10), a distal lateral incision was made in the animal’s right thigh, where the sciatic nerve was exposed until the nerve trifurcation was visualized (Figure 1). The tibial nerve was then identified, and this nerve was sectioned. Subsequently, the distal part of the sectioned nerve was buried in the musculature to avoid the formation of a glioma. We created a subcutaneous tunnel for the proximal stump and the sectioned nerve was fixed just below the skin, 1 cm above the lateral malleolus. Thus, the suture

material was visible and was used as a target for both the dissection and use of the cryotherapy machine, as well as for the mechanical stimuli that induced neuroma pain. In the sham group (n=5), the tibial nerve was dissected using the technique described above and left intact. After 24 and 48 hours of the surgical procedure, meloxicam (1 mg/kg) + tramadol (10 mg/kg) was administered to all animals, for analgesic and anti-inflammatory purposes.

Figure 1: Lateral incision in the animal’s right thigh, through which the sciatic nerve was exposed.

Cryotherapy Use

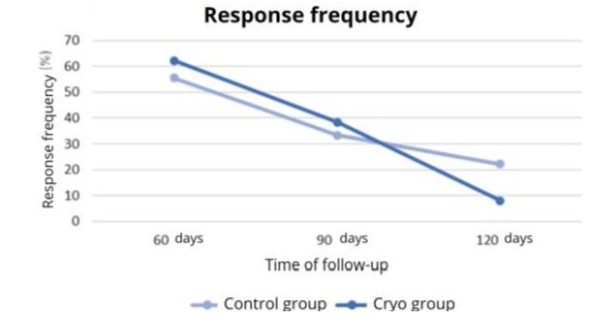

Sixty days after the tibial nerve transection, the 10 rats in the Cryotherapy Group were treated with cryotherapy at the site of the neuroma formation using the Cryo-S Painless device (Figure 2). The animals were pre-anesthetized with fentanyl (0.16 mg/kg - sc) followed by anesthesia with a solution consisting of meloxicam (2 mg/kg) + tramadol (10 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) + ketamine (90 mg/kg) intraperitoneally. To maintain the animal in the anesthetic plane, we used 3% isoflurane by inhalation. Cryotherapy was performed after opening the skin and identifying the neuroma, in two cycles of 2 minutes with 30-second intervals between one cycle and the other, at a temperature of -70ºC.

Figure 2: Use of cryotherapy. Neuroma observed microscopically 60 days after the tibial nerve was sectioned (A). Procedure with the Cryo-S Painless device (B). Microscopic image of the moment of freezing (C).

Behavioral Test with Mechanical Stimuli

The behavioral tests to assess tissue sensitivity to mechanical stimuli were performed in accordance with the study by Dorsi et al. [24] and were performed in a quiet room by three trained observers 60, 90, and 120 days after the surgical procedure. The animals were placed in individual transparent plastic cages with a 2.5 x 2.0 cm window in the lower part of the side walls of the cages, allowing the use of the orange Von Frey filament (10 g) to the target region of the paws. Before the start of the tests, they were acclimated to the environment for 20 minutes. The test was performed with five applications of an orange Von Frey filament for 1–2 s, with an interstimulus interval of 2 s. If the animal responded positively (felt pain or discomfort) to any of the five applications, the test was terminated, and a new application of the monofilament was not necessary in that test. A positive response was defined as a slow or rapid withdrawal of the hind paw, vocalization, licking, or animal restlessness. The test was then performed 5 more times, with a 2-minute interval between them. To qualitatively assess tissue sensitivity, we used a classification system also used by Dorsi et al. [24], in which a grade ranging from 0 to 2 is assigned to the animal response. A grade of 0 indicated that the animal did not respond to the stimulus, a grade of 1 response represented a slow withdrawal of the paw, and a grade 2 response represented a sudden withdrawal or restlessness, licking, or vocalization. The Withdrawal Score (WS) is defined as the sum of the response scores for the five trials and ranged from 0 to 10. To assess quantitatively, we used the Response Frequency (RF), which is the percentage of positive tests out of the five trials (100 x number of positive tests, divided by 5).

Histological Analysis

After 120 days of study, all rats were euthanized with an overdose of anesthetic (with a solution consisting of xylazine (20 mg/ kg) + ketamine (180 mg/kg) intraperitoneally. A new incision was made over the previous incisions to remove the tibial nerve for histological analysis. The collected samples were fixed in 10% formalin. After fixation, the material was dehydrated in increasing concentrations of alcohol, diaphanized in xylene and embedded in paraffin. Paraffin blocks were prepared, and histological sections were made from the blocked material with a maximum thickness of 4 micrometers using a rotary microtome. After the microtomy, the sections were placed in an oven. The sections were then stained according to the following protocol: deparaffinization in an oven at 45°C for 40 minutes, followed by two 10-minute xylene baths. minutes each. The tissue was then hydrated with baths of decreasing concentrations of ethyl alcohol (100%, 90% and 80%) for 5 minutes each and washed in water for 7 minutes. Next, staining with hematoxylin for 3 minutes was performed, followed by washing in water for 3 minutes and staining with eosin for 15 minutes. The tissue was dehydrated by baths of increasing concentrations of ethyl alcohol (70% and 80%) for 5 minutes and two baths of ethyl alcohol (100%) for 3 and 5 minutes. The material was fixed with two baths in xylene for 5 and 10 minutes. The process was completed by mounting the slides with the insertion of the coverslip fixed with Entellan. The number of vessels was assessed quantitatively by using a digital image analysis system consisting of a microscope (Olympus bx51) with plan achromatic objectives, coupled to a camera (Oly-200) and a microcomputer with the Image Pro-Plus software, running in a Windows environment.

To measure the number of vessels, 1 image of each case was digitized at x200 magnification, using the hot spot principle. The analysis of the digitized images was performed by two observers, without prior knowledge of the groups. The mean and median values for each case were calculated from the absolute numerical values obtained.

To assess the influence of cryotherapy on neural tissue regeneration, we used the SOX10 protein antigen as a marker to assess the presence of Schwann cells in the nerves of the three groups. Antigen retrieval was performed using the PT Link equipment, Agilent (USA), by immersing the slides in 10 mM citrate buffer, pH 6.0. Using the Leica Novolink kit, the slides were processed as follows: first, the endogenous peroxidase was neutralized, and the slides were washed. Then, the protein blocking agent was applied and then incubated with the primary SOX10 antibody (diluted 1/100) for 40 minutes. After further washing, they were incubated with the primary powder and polymer, with washing between each step. Development was performed with diaminobenzidine (DAB) for 2 to 5 minutes. The slides were then counterstained with Harris hematoxylin, dehydrated in alcohol and xylene, and mounted with Entelan (Merck). This protocol ensures the correct preparation of the slides for analysis of SOX10 protein expression. The same abovementioned digital analysis system was used. As in the measurement of the vessels, 1 image of each slide was digitized at x200 magnification, using the hot spot principle. The ratio between the image capture area (the same for all) and the area occupied by the antigen reaction with Schwann cells was then calculated. A descriptive statistical analysis was performed on this value and values f or mean, amplitude, standard deviation and variance were found. In some slides, the antigen reaction failed, compromising the final image. These were discarded from the study.

Results

Behavioral Test with Mechanical Stimuli

The data collection forms were edited after checking for missing data, inaccuracies in filling out the forms, and the creation of variables. Data cleaning programs were developed to assess

inconsistencies in the data and prepare the database for subsequent analyses. The data were analyzed using the STATA 14.0 program (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Tables of central tendency and dispersion measures were used for descriptive analyses. The effect of the type of treatment on the evaluated outcomes was investigated using generalized estimating equations (GEE) models. For all tests, a p-value less than or equal to 0.05 was considered significant. A total of three animals in the Cryo Group did not complete the 3 follow-up points, and this factor was considered in the evaluation using Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE). A total of 17 individuals were evaluated in this study and allocated to the Control Group (neuroma without cryotherapy) (n=10) and Cryotherapy Group (n=7). The outcomes of Response Frequency (RF) and Withdrawal Score (WS) were evaluated at 60, 90 and 120 days after the procedure. Table 1 shows the RF values of the different groups at the different times.

|

Time 60 days |

Time 90 days |

Time 120 days |

|

|

Group |

mean±sd (median) |

mean±sd (median) |

mean±sd (median) |

|

Control Group |

55.56±32.83 (60) |

33.33±33.17 (40) |

22.22±34.92 (10) |

|

Cryotherapy Group |

62.22±44.10 (80) |

44.00±38.47 (40) |

8.00±8.36 (10) |

Table 1: RF values of different groups at different times.

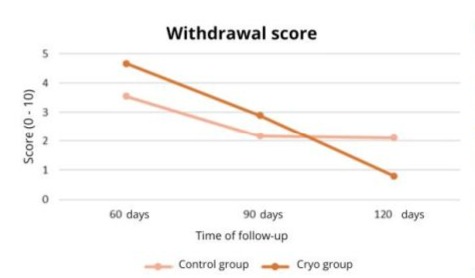

Figure 3 shows the variation in Response Frequency at different postoperative times.

Figure 3: Variation in RF at different postoperative times according to the study group.

The analysis of Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) models indicates a significant effect of the type of treatment on the RF at 120 days (p<0.001) Table 2 shows the WS values of the different groups at the different times.

|

Time 60 days |

Time 90 days |

Time 120 days |

|

|

Group |

mean±sd (median) |

mean±sd (median) |

mean±sd (median) |

|

Control Group |

3.55±2.24 (4) |

2.17±2.29 (2) |

2.11±3.22 (1) |

|

Cryotherapy Group |

4.67±3.83 (6) |

2.90±3.54 (2) |

0.80±0.84 (1) |

Table 2: Withdrawal Score values of the different groups at different times.

Figure 4 shows the variation in the Withdrawal Score at different postoperative times.

Figure 4: Variation of WS at different postoperative times according to the study group.

The analysis of generalized estimating equations (GEE) models indicates a significant effect of the type of treatment on WS at 120 days (p=0.038). Therefore, there was no statistically significant difference between the Control Group and the Cryotherapy Group in relation to the Response Frequency and Response Score at 60 and 90 days post-treatment. There was a statistically significant difference between the Control Group and the Cryotherapy Group in relation to the Response Frequency and Response Score at 120 days post-treatment, as the Cryotherapy Group showed a lower Response Frequency and a lower Withdrawal Score when compared to the Control Group.

Histological Evaluation

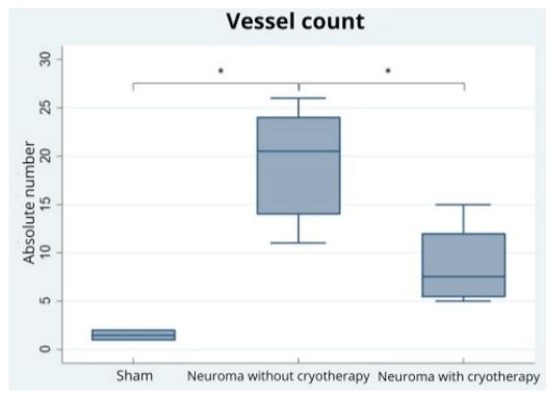

A) Analysis of the Number of Vessels

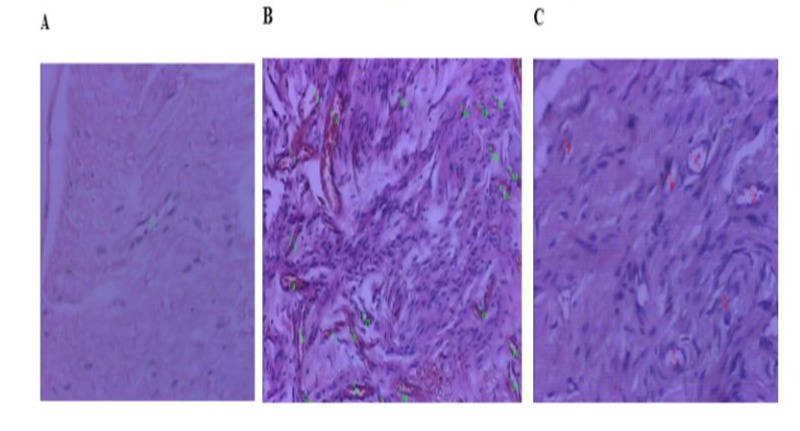

The data were analyzed using the STATA 14.0 program (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Tables of central tendency and dispersion measures were used for the descriptive analyses. The normal distribution of the sample was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The differences in blood vessel counts of the individuals in the three groups were compared using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni post-hoc analyses. For all tests, a p-value less than or equal to 0.05 was considered significant. After the preparation described above, 14 slides were considered suitable for analysis of the number of blood vessels by the Pathology Department and were allocated to the Sham Group (n=4), Control Group (neuroma without cryotherapy) (n=6) and Cryotherapy Group (n=4). Slides that did not show adequate representation of the area of interest, which allowed histological evaluation, were excluded. There was no statistical impact on the final result of the study. Table 3 shows the blood vessel count values of the different groups. Figure 6 shows the microscopic image of one slide from each group with the blood vessel count, digitized at x200 magnification, using the hot spot principle. Figure 7 shows the difference in the appearance of the neuroma in the Control group and the Cryotherapy group at the end of the study.

|

Sham |

Control Group |

Cryotherapy Group |

|

|

Variable |

mean±sd (median) |

mean±sd (median) |

mean±sd (median) |

|

Vessel count |

1.50±0.58 (1.5) |

19.33±5.85 (20.5) |

8.75±4.50 (7.5) |

Table 3: Vessel count values of the different groups.

The vessel count variable showed a normal distribution (p=0.1549) and, therefore, a parametric ANOVA test was performed. The ANOVA test indicated a statistically significant difference in the vessel count between the groups (p=0.0003). The Bonferroni test showed a statistically significant difference between the Sham and Cryotherapy Groups in relation to the Control Group, with p<0.001 and p=0.013, respectively. There was no statistically significant difference between the Sham Group and the Cryotherapy Group (p=0.143).

Figure 5 depicts the observed differences.

Figure 5: Box-plot graphs for vessel counts in the three groups. The sign (*) indicates statistically significant difference (p<0.05).

Therefore, the vessel count in the Control Group is statistically higher than in the Sham Group and the Cryotherapy Group.

Figure 6: Histological evaluation of the number of vessels, scanned at x200 magnification, using the hot spot principle. Slide from the Sham Group, with only 1 vessel (A). Slide from the Control Group, with an increase in the number of vessels (B). Cryotherapy Group (C).

Figure 7: Microscopic visualization of the tibial nerve at the end of the study. Neuroma in the Control Group (A). Neuroma in the Cryotherapy Group (B).

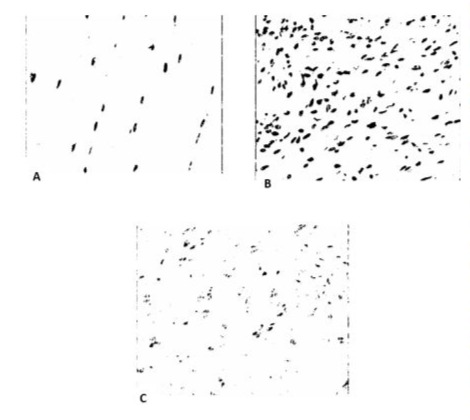

B) Analysis of the Number of Schwann Cells

After preparing the slides with the SOX10 protein antigen, 16 slides were considered suitable by the Pathology department for the analysis of the presence of Schwann cells in the different groups at the end of the study, being allocated to the Sham Group (n=3), Control Group (neuroma without cryotherapy) (n=8) and Cryotherapy Group (n=5). In some slides, failure of the reaction to the antigen was observed, compromising the final image, and these were discarded from the study. Tables 4, 5 and 6 show the values of the ratio (Mean2) between the capture area and the area of t he SOX 10 protein reaction, represented by the dark area. From this value, we analyzed the mean, amplitude and standard deviation between the groups. The number of samples can influence the reliability of the means, with the Neuroma control group being more representative. Figure 8 shows the microscopic image of a slide from each group after the reaction, scanned at x200 magnification, using the hot spot principle. Tables 4, 5 and 6. Value of the ratio (Mean2) between the image capture area and the area occupied by the antigen reaction with Schwann cells in each group.

Image capture area: 414720 µm

|

Samples |

Group |

Code |

Mean2 (µm) |

|||

|

1 |

Sham |

R2 |

2,588 |

|||

|

2 |

Sham |

R3 |

4,911 |

|||

|

3 |

Sham |

R5 |

2,991 |

|||

|

Samples |

Group |

Code |

Mean2 |

|||

|

(µm) |

||||||

|

1 |

Neuroma without/cryo |

R6 |

14,424 |

|||

|

2 |

Neuroma without/cryo |

R7 |

0,384 |

|||

|

3 |

Neuroma without/cryo |

R8 |

11,399 |

|||

|

4 |

Neuroma without/cryo |

R10 |

1,791 |

|||

|

5 |

Neuroma without/cryo |

R11 |

0,864 |

|||

|

6 |

Neuroma without/cryo |

R12 |

14,761 |

|||

|

7 |

Neuroma without/cryo |

R13 |

22,258 |

|||

|

8 |

Neuroma without/cryo |

R14 |

13,527 |

|||

|

(µm) |

||||||

|

1 |

Cryotherapy |

R15 |

1,200 |

|||

|

2 |

Cryotherapy |

R16 |

1,044 |

|||

|

3 |

Cryotherapy |

R17 |

11,837 |

|||

|

4 |

Cryotherapy |

R18 |

12,465 |

|||

|

5 |

Cryotherapy |

R19 |

3,351 |

|||

Tables 4,5,6: Value of the ratio (Mean2) between the image capture area and the area occupied by the antigen reaction with Schwann cells in each group.

The Control group, with 8 samples and a mean of 9,926, shows high mean values due to nerve regeneration after the injury and, consequently, a greater proliferation of Schwann cells, which react with the Sox10 protein antigen. The Cryotherapy group, with 5 samples and an intermediate mean of 5,979, indicates that cryotherapy may be reducing the proliferation of these cells, resulting in lower reaction with this antigen and, therefore, lower Mean2 values.

|

Sham |

Control Group |

Cryotherapy Group |

|

|

Mean |

3,496 |

9,926 |

5,979 |

Table 7: Mean values in the different groups.

In the Sham group, with an amplitude of 2,324, the values vary less compared to the other groups, indicating less variability in the data. The Neuroma group without cryotherapy (Control Group), with an amplitude of 21,874, shows the greatest variation between the values, reflecting the large total extension of the data due to the significant proliferation of Schwann cells. The Cryotherapy group, with an amplitude of 11,422, has a variation that is between the values of the other two groups, but still shows greater variability in relation to the Sham group.

|

Sham |

Control Group |

Cryotherapy Group |

|

|

Amplitude |

2,324 |

21,874 |

11,422 |

Table 8: Amplitude Values In The Different Groups.

It can observed, in the first group, that the measurement values are less dispersed, reflecting a lower variability of the data due to the absence of intervention. In the Control group, there is a large dispersion of the values due to the large amount of Schwann cells, resulting from the proliferation of nerve cells, causing high variability. In the Cryotherapy group, with a standard deviation of 5.712, the dispersion of the values i s lower than in the group without cryotherapy, indicating that the intervention may be slowing down nerve regeneration, evidenced by a lower reaction with the Sox10 protein antigen and, consequently, a lower variability in the values. Although cryotherapy shows a moderating effect, the variability is still greater when compared to the Sham group.

|

Sham |

Control Group |

Cryotherapy Group |

|

|

Standard deviation |

1,242 |

8,019 |

5,712 |

Table 9: Standard Deviation values in the different groups.

Figure 8: Digitized images at x200 magnification, showing the reaction of Schwann cells with the SOX10 protein antigen (dark area). Slide from the Sham Group (A). Slide from the Control Group, with an increase in the number of cells (B). Cryotherapy Group (C).

Discussion

Post-traumatic neuroma is the result of neural tissue proliferation after damage or transection of a nerve bundle [1]. After an injury occurs, the proximal portion of the nerve seeks to regenerate itself and reestablish the innervation of the distal segment through the growth of axons inside the tubules of proliferative Schwann cells [1-3]. When there is no well-structured tissue, the regenerating elements still initiate the reinnervation process, resulting in the disorganized growth of a mass, similar to a tumor, at the injury site, which is called a neuroma [1,4-6]. This process can be observed 28 days after the nerve injury. In our study, we preferred to use the time period of 60 days after the sectioning of the tibial nerve to perform the intervention with cryotherapy, based on the work published by Oliveira et al. [20]. In this study, microscopy showed that 28 days after nerve injury, signs of neuroma formation were already observed, such as the presence of axonal sprouts, axons grouped in a disorganized manner, and degenerating axons. However, after 60 days, these changes were more evident and concrete. We also determined a four-month interval between nerve injury and euthanasia of the animals, since this is enough time for complete nerve regeneration [25,26] and because we know that, after this period, the nerve will not undergo major biological changes. Observing the results of the behavioral test in the second and third months of the study, we noticed that, despite the drop in the graph, the Cryotherapy Group attained higher Withdrawal Score and Response Frequency values than the other group, becoming lower and with a statistically significant difference only after 120 days. We believe that freezing the nerve caused pain in the first months after the intervention. Perhaps the temperature of the procedure (-70ºC) and/or the time of probe application (two 2-minute cycles, with 30-second intervals between them) caused an exacerbated inflammatory response in all animals. Three rats were lost in the Cryotherapy Group. They died a few hours after the procedure, even with constant supervision by our biologist and a strong analgesic regimen. Apart from these, the other animals did not have any complications and were able to reach the end of the study. Moesker et al. [22] used a similar freezing protocol in their study, which consisted of treating patients diagnosed with phantom limb pain. Maintaining the number of cycles, the probe was applied for three minutes on the neuroma of the amputated stump. Florete et al. [21], in turn, used the same temperature and duration of this study to treat patients with chronic neck pain, also reporting that, for 10 to 14 days, they could complain of pain in the region. DeLeo et al. [27] used cryotherapy to generate lesions in the sciatic nerve of rats.

The procedure consisted of one freezing cycle at -60ºC for 30 seconds, with a 5-second thawing interval. Therefore, the method used in our study may have been too strong for the animals, causing undesirable results. Perhaps with an adjustment in the temperature and time of probe application, the freezing effectiveness would be greater and the response to neuroma pain would occur earlier. Another factor that was observed in the Withdrawal Score and Response Frequency graphs was the drop in these values in the Control Group. Without any intervention in this group, the level of pain caused by the neuroma was expected to remain high or even increase over the months. In addition to the mechanical barrier caused by the growth and fattening of the animals during the study, another factor that may have contributed to this fact was that, at the end of the study, when we removed the nerves for histological evaluation, we observed that some neuromas were either surrounded by a fibrosis layer or had migrated to the muscles of the animal’s thigh. This may have influenced the animal’s response to the application of the monofilament, causing an unrealistic result. Regarding the histological assessment, after the preparation described above, 14 slides were considered suitable for the analysis of the number of vessels by the Pathology department. There was no statistical impact on the result of the study. We wanted to test whether the use of cryotherapy would influence the formation of new vessels in the proximal stump, inhibiting the neuroma growth and development. Cattin et al. [28] observed in their work with rats that, in 95% of them, after two days of nerve injury, a connection was formed between the proximal and distal stumps (which they called a “bridge”), consisting mainly of macrophages and neutrophils, with fibroblasts and endothelial cells in smaller proportions. However, on the third day, a significant increase in endothelial cells and blood vessels was observed in this region, originating from the nerve stumps. Zochodne et al. [29], in turn, studied the angiogenesis in the proximal stump of a neuroma caused after sciatic nerve injury in rats. The authors observed that, after 7 days, this process had already occurred, with an increase in the vasa nervorum, an increase in small-diameter vessels and an increase in the area of the neuroma occupied by endothelial cells.

At the end of this study, we observed, through histological evaluation, that the Sham group and the Cryotherapy group had few blood vessels in the count, with no statistical difference between them. In contrast, in the group in which we caused the nerve injury, but did not use cryotherapy, we saw a large number of vessels on the slides compared to the other two groups, with a statistical difference between them. With the decrease in the number of vessels, there is a decrease in the migration of other cells such as lymphocytes and macrophages, responsible for the activation of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-10, and TNF-alpha, known to be involved in post-traumatic neurological pain [7]. We also investigated in the histological analysis, the impact of cryotherapy on nerve regeneration, using the SOX10 protein antigen as a marker to evaluate the presence of Schwann cells in the injured nerves. The SOX10 protein, belonging to the SOX (SRY-related HMG-box) family, is an essential transcription factor that plays a key role in nerve regeneration after injury, both in the Central Nervous System (CNS) and in the Peripheral Nervous System (PNS). In the CNS, SOX10 is crucial for the maturation and maintenance of oligodendrocytes, the cells responsible for the formation of the myelin sheath. Myelin is an insulating layer that surrounds axons, allowing the rapid conduction of nerve impulses. After an injury to the CNS, axon regeneration is limited, but SOX10 helps in the remyelination of damaged axons, promoting the differentiation of oligodendrocyte precursors into mature cells capable of repairing the myelin sheath. This process is crucial for restoring the functionality of damaged neurons and improving post-injury recovery. In the PNS, this protein plays a similar role in Schwann cells, which are responsible for the myelination of peripheral axons. After a peripheral nerve injury, Schwann cells dedifferentiate, proliferate, and migrate to the site of injury, where they help remove cell debris and facilitate axon regeneration. SOX10 is essential for regulating the expression of genes involved in these processes, ensuring that Schwann cells can effectively support nerve regeneration. The descriptive statistical analyses indicated significant differences between the groups. In the Sham Group, the reaction to the SOX10 protein antigen was minimal, as expected, since the nerves were not injured. The presence of Schwann cells was observed at basal levels, consistent with the normal function of maintaining intact nerve fibers. In the Control Group, a marked reaction to the SOX10 protein antigen was observed, indicating significant proliferation of Schwann cells. This increase is a natural body response to nerve injury, where Schwann cells proliferate and migrate to the injury site. These cells play a critical role in the phagocytosis of cell debris and in the formation of Bungner bands, which guide axon regeneration. The intense SOX10 reaction in this group confirms the high regeneration activity, but also suggests a potential risk of neuroma formation due to the uncontrolled proliferation of Schwann cells. Finally, in the Cryotherapy Group, there was a significant reduction in the SOX10 protein antigen reaction, indicating a lower proliferation of Schwann cells in comparison to the control group. The results suggest that cryotherapy has a modulatory effect on the regenerative response after nerve injury. The reduction in Schwann cell proliferation observed in the cryotherapy group may be beneficial in preventing the formation of neuromas, which are a common complication after nerve injuries and can cause chronic pain and neurological dysfunction. Modulation of the inflammatory response and reduction of local metabolism by cryotherapy may be key mechanisms behind these effects.

This study had some limitations. The behavioral test may have been influenced by the animal’s growth, as well as its fattening. This would create a mechanical barrier between the monofilament application and the neuroma. Another factor that may have contributed to the distortion of some results was the neuroma migration, previously fixed on the animal’s skin, to deeper tissues. In future studies, a more effective method of fixing the neuroma to the skin will be better for the test effectiveness. Regarding the freezing of the nerve, as mentioned above, the temperature and duration of the procedure may have caused an exacerbated and undesirable inflammatory reaction, resulting in the death of three rats and influencing the behavioral test. Therefore, it would be necessary to adapt it for experiments carried out in rats and to study the ideal time and temperature to perform the freezing of the neuroma in humans, to avoid postoperative pain and other complications. Regarding the comparison of the number of Schwann cells, this study also had limitations. First, not all slides were considered suitable for evaluation after reaction with the SOX10 antigen. This resulted in a reduction in the number of slides available for comparison between the experimental groups, which compromised the ability to perform statistically significant analyses. Moreover, a significant variation in the number of Schwann cells was observed between slides within the same experimental group. This intra-group variability introduced an additional source of variability in the data, making it even more difficult to detect statistical differences between the groups. Due to these limitations, the statistical evaluation of the present study was restricted to descriptive analyses, and it was not possible to perform formal statistical comparisons between the groups. Future studies can explore methods to attenuate these sources of variability and increase the robustness of statistical analyses, thus improving the reliability and interpretation of the obtained results.

Conclusion

The results obtained in the behavioral test showed that, at the end of the experiment, the group of animals submitted to cryotherapy had a better response to painful stimuli than the ones that were not submitted to this procedure. Likewise, in the histological analysis, freezing the nerve proved to be effective in preventing the process of angiogenesis and proliferation of Schwann cells, reducing the risk of neuroma formation, normally seen after nerve injury. This finding is of great relevance for the development of therapeutic strategies that aim to improve recovery after nerve injuries, balancing the need for regeneration and the control of excessive cell proliferation. Therefore, our study demonstrated that the use of cryotherapy in the treatment of neuroma in rats showed to be effective.

References

- Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouquot JE (2004) Patologia: Oral & Maxilofacial. 2ª ed. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan.

- Sheridan SM (1983) Traumatic neuroma following sagittal split mandibular osteotomy. Br J Oral Surg 21: 198-200.

- Kallal RH, Ritto FG, Almeida LE, Crofton DJ, Thomas GP (2007) Traumatic neuroma following sagittal split osteotomy of the mandible. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 36: 453-454.

- Pérusse R (1994) Acoustic neuroma presenting as orofacial anethesia. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg 23: 156-160.

- Lee EJ, Calcaterra TC, Zuckerbraun L (1998) Traumatic neuromas of the head and neck. Ear, Nose Throat J 77: 670-674.

- Huang LF, Weissman JL, Fan C (2000) Traumatic neuroma after neck dissection: CT characteristics in four cases. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 21: 1676-1680.

- Khan J, Noboru N, Young A, Thomas D (2017) Pro and anti-inflammatory cytokine levels (TNF-a, IL-1b, IL-6 and IL-10) in rat model of neuroma. Pathophysiology 24: 155-159.

- Janes S, Renaut PH, Gordon MK (2004) Traumatic (or amputation) neuroma. ANZ J Surg 74: 701-702.

- Konig HJ, Themann H, Hiller U, Gullotta F (1987) Prevention of neuroma formation by Neodym Yag laser - Experimental observations. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 87: 65-69.

- Yüksel F, Kislaoglu E, Durak N, Ucar C, Karacaoglu E (1997) Prevention of painful neuromas by epineural ligatures, flaps and grafts. Br. J. Plast. Surg 50: 182-185.

- Dagum AB (1998) Peripheral nerve regeneration, repair, and grafting. J. Hand Ther 11: 111-117.

- Aszmann OC, Korak KJ, Rab M, Grunbeck M, Lassmann H, et al. (2003) Neuroma prevention by end-to-side neurorrhaphy: An experimental study in rats. J. Hand Surg. Am 28: 1022-1028.

- Mackinnon SE, Dellon AL, Hudson AR, Hunter DA (1985) Alteration of neuroma formation by manipulation of its microenvironment. Plast. Reconstr. Surg 76: 345-353.

- Rasmussen OC (1980) Painful traumatic neuromas in the oral cavity. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol 49: 191-195.

- Lewin-Kowalik J, Marcol W, Kotulska K, Mandera M, Klimczac A (2006) Prevention and management of painful neuroma. Neurol. Med. Chir. (Tokyo) 46: 62-67.

- Karev A, Stahl S (1986) Treatment of painful nerve lesions in the palm by “rerouting” of the digital nerve. J. Hand Surg Am 11: 539-542.

- Evans GR, Dellon AL (1994) Implantation of the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve into the pronator quadratus for treatment of painful neuroma. J. Hand Surg. Am 19: 203-206.

- Sood MK, Elliot D (1998) Treatment of painful neuromas of the hand and wrist by relocation into the pronator quadratus muscle, J. Hand. Surg Br 23: 214-219.

- Hazari A, Elliot D (2004) Treatment of end-neuromas, neuromas-incontinuity and scarred nerves of the digits by proximal relocation. J. Hand Surg Br 29: 338-350.

- Oliveira KMC, Pindur L, Han Z, Bhavsar MB, Barker JH, et al. (2018) Time course of traumatic neuroma development. PLoS ONE 13: e0200548.

- Florete OG (2019) Cryoablative Procedure For Back Pain.

- Moesker AA, Karl HW, Trescot AM (2014) Treatment of phantom limb pain by cryoneurolysis of the amputated nerve. Pain Pract 14: 52-56.

- CEUA / UNIFESP (2017) Guia de anestesia e analgesia em animais de laboratório. São Paulo: Comissão de Ética no Uso de Animais.

- Dorsi MJ, Chen L, Murinson BB, Pogatzki-Zahn EM, Meyer RA, et al. (2008) The tibial neuroma transposition (TNT) model of neuroma pain and hyperalgesia. Pain 134: 320-334.

- Politis MJ, Ederle K, Spencer PS (1982) Tropism in nerve regeneration in vivo. Attraction of regenerating axons by diffusible factors derived from cells in distal nerve stumps of transected peripheral nerves. Brain Res 253: 1-12.

- Brushart TM, Tarlov EC, Mesulam MM (1983) Specificity of muscle reinnervation after epineurial and individual fascicular suture of the rat sciatic nerve. J Hand Surg Am 8: 248-53.

- DeLeo JA, Coombs DW, Willenbring S, Colburn RW, Fromm C, et al. (1994) Characterization of a neuropathic pain model: sciatic cryoneurolysis in the rat. Pain 56: 9-16.

- Cattin AL, Burden JJ, Van Emmenis L, Mackenzie FE, Hoving JJA, et al. (2015) Macrophage-Induced Blood Vessels Guide Schwann CellMediated Regeneration of Peripheral Nerves. Cell 162: 1127-1139.

- Zochodne DW, Nguyen C (1997) Angiogenesis at the site of neuroma formation in transected peripheral nerve. J Anat 191: 23-30.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.