Conversion of Central Sleep Apnea to Obstructive Sleep Apnea by Cpap Therapy in Heart Failure Patients

by Keith Burgess1,2,5* and Norbert Berend3,4

1Northern Beaches Hospital Australia

2Peninsula Sleep Clinic Australia

3University of Sydney Australia

4Woolcock Institute of Medical Research Australia

5Macquarie university Australia

*Corresponding author: Keith Burgess, Peninsula Sleep Clinic Suite 3, Level 2. Building 1.49 Frenchs Forest Road E. Frenchs Forest. Sydney. NSW. 2086 Australia.

Received Date: 10 February, 2026

Accepted Date: 16 February, 2026

Published Date: 18 February, 2026

Citation: Burgess K and Berend N (2026) Conversion of Central Sleep Apnea to Obstructive Sleep Apnea by Cpap Therapy in Heart Failure Patients. Cardiol Res Cardio vasc Med 11:295. DOI: https://doi.org/10.29011/2575-7083.100295

Abstract

Study Objectives: It was hypothesised that in patients with heart failure and central sleep apnea (CSA), individually titrated CPAP therapy would reduce afterload and catecholamine levels, hence lead to improvement in cardiac status and CSA. Methods: Five adult patients with congestive heart failure due to dilated cardiomyopathy complicated by CSA were enrolled. They were treated with continuous positive airways pressure (CPAP) at individualised pressures ranging between 10 and 16cm H2O. 5 subjects were restudied after 3 months and 4 subjects after 12 months of treatment. CPAP compliance was objectively documented. Results: Central apnea hypopnea index (AHI) fell from 51±14/hr to 3±5/hr over 12 months (p<0.01). Surprisingly the obstructive AHI increased from 4±5/hr to 31±15/hr over the same period (NS). Stage 1 sleep fell from 44±18% to 13±5% (p<0.05), Stage 2 increased from 36±16% to 59±8% (p=0.01), and REM sleep from 10±5% to 18±4% (p=0.01)]. Cardiac index increased, vascular resistances fell and six minute walk distance increased from 344±51m to 459±81m (p=0.05). PaCO2 awake increased from 38±5 to 41±5mmHg. Lung water fell from 10.6±2.1 to 8±2.3ml/kg (both NS). Night time plasma noradrenaline levels fell from 5.8±2.4 to 1.9±1.6 nmo/l (p<0.01). There were no confounding changes in body mass index or medications. Conclusion: The clinical importance of these findings is that in patients with severe cardiac failure complicated by CSA, CPAP therapy is likely to improve cardiac function with resolution of the CSA, and development of OSA. This may require revision of our approach to CPAP therapy.

Abbreviations

ACE- Angiotensin Converting Enzyme; AHI - Apnea Hypopnea Index; ANOVA- Analysis of Variance Analysis; BMI- Body Mass Index; CCF- Congestive Cardia Failure; CI - Cardiac Index; CPAP - Continuous Positive Airways Pressure; CSA- Central Sleep Apnea; EVLW - Extra Vascular Lung Water; HPLC - High Pressure Liquid Chromatography; OSA- Obstructive Sleep Apnea; PAOP- Pulmonary Artery Occlusion Pressure ; PCO2 - Pressure of Carbon Dioxide; REM sleep - Rapid Eye Movement Sleep; NREM sleep - Non-Rapid Eye Movement Sleep; SVRI - Systemic Vascular Resistance Index

Brief Sumary

Current Knowledge: Congestive heart failure (CCF) is known to cause central sleep apnea (CSA) if severe enough, although the mechanisms are not fully understood. CPAP therapy has been shown in small studies to improve CSA, but conversion to OSA has not been described.

Study Impact: Individualised CPAP therapy resolved CSA. but the patients then converted to severe OSA. This may require revision of CPAP therapy approaches in CCF patients.

Keywords: Central Sleep Apnea, CSA, Obstructive Sleep Apnea, OSA, CPAP Therapy, Heart Failure.

Introduction

Central Sleep Apnea (CSA) is common in patients with congestive heart failure (CCF), occurring in approximately 40% of patients with very severe CCF [1, 2]. It is associated with a higher mortality than Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) (Agrawal3). Possible mechanisms include a combination of “classical factors”:

a. Elevated central respiratory drive; In CCF patients the increased drive is usually an increased ventilatory response to CO2 [3,4], possibly due to reduced cerebral perfusion causing accumulation of brain PCO2 [5]. It may also be due to J receptor 6stimulation from pulmonary congestion ± increased circulatory catecholamines [7-9] which are a feature of CCF. This causes hypocapnia [10,11].We hypothesised that in patients with heart failure and central sleep apnea (CSA), individually titrated CPAP therapy would reduce afterload and catecholamine levels, hence lead to improvement in cardiac status and CSA.

Methods

Ethical Approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee (Northern Sydney LHD Human Research and Ethics Committee 1995) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Five adult male subjects with left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 30% and evidence of Central Sleep Apnea (CSA) on Polysomnography (PSG) were recruited from eight referred patients. One declined consent and two no longer met the above inclusion criteria. After giving informed consent, they underwent a series of baseline investigations as follows: McMaster Chronic Heart Failure [17] quality of life questionnaire, six-minute walk test [18,19], pulmonary artery catheterisation, measurement of extravascular lung water [20,21], and measures of morning and evening plasma catecholamine levels.

The subjects also underwent a CPAP pressure determination study. They were then commenced on nasal CPAP therapy at an individually determined pressure. The patient details are shown in (Table 1).

|

Subject# |

Age (yrs) |

BMI* |

CPAP Pressure** |

|

1 |

51 |

35.9 |

16 |

|

2 |

68 |

23.1 |

11 |

|

3 |

78 |

24.2 |

10 |

|

4 |

70 |

23.9 |

14 |

|

5 |

70 |

25.9 |

14 |

|

Mean |

67 |

26.6 |

13 |

|

SD |

10 |

5.3 |

2 |

|

+ kg/m2 ** cm H2O |

|||

Table 1: Subject Characteristics

Four of the five patients underwent concealed testing of CPAP compliance during the treatment phase by substituting their existing CPAP machine with a CPAP machine containing a recording device. The fifth subject withdrew from the study at three months before this could be done.

The subjects’ medications were all documented throughout the duration of the study. Although all subjects were on an angiotenson converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor, only one subject was taking a beta-blocker (Metoprolol), with reduction of the dose. On balance the dosage of diuretics and ACE inhibitors were unchanged over the twelve-month period.

The PSGs were all scored by the same certified polysomnographer in accordance with accepted criteria in 2000 [22-24].

The optimal CPAP – pressures were titrated according to accepted techniques [24]. If there were no obstructive events on the night, then an arbitrary pressure of 10cmH2O was used as suggested by Naughton et al [13]. Extra Vascular Lung Water (EVLW) was measured using the double indicator dilution technique [21]. The Quality of Life questionnaire had been previously validated by others [17]. The pulmonary artery catheter insertion and measurements of haemodynamic variables were carried out according to published methods [25]. The plasma samples for catecholamine assay were collected on ice, centrifuged immediately then frozen. They were subsequently assayed by High Pressure Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) at a reference laboratory.

Statistical Analysis

The data were analysed using Statview v4.5 for the Macintosh (Abacus Concepts Inc. Berkeley. CA. USA). Results were compared over time by analysis of variance with repeated measures (ANOVA) [26]. Fishers PLSD post-hoc test was then applied to determine the level of significance between times. No attempt was made to correct for missing values.

Results

The results of the treatment with CPAP are shown in (Tables 2-5. Table 2) shows the changes in obstructive and central events over time. (Table 3) shows the changes in sleep architecture.

|

Sleep architecture |

Baseline |

3 Months |

12 Months |

|

% Stage 1 |

44 ± 18 |

21 ± 19* |

13 ± 5* |

|

% Stage 2 |

36 ± 16 |

46 ± 4 |

59 ± 8*** |

|

% Stage 3 & 4 |

9 ± 9 |

14 ± 14 |

9 ± 6 |

|

% REM Sleep |

10 ± 5 |

20 ± 7* |

18 ± 4** |

|

Means ± 1 SD * p < 0.05 ** p = 0.01 *** p < 0.01 compared to baseline Fishers PLSD compared to baseline after ANOVA Arousal Index: Arousals per hour of sleep Apnea Hypopnea Index: Apneas and hypopneas per hour of sleep |

|||

Table 3: Sleep Architecture

|

Cardiovascular Parameter |

Baseline (n=5) |

3 Months (n=5) |

12 Months (n=4) |

|

Cardiac Index l/min/m2 |

1.7 ± O.3 |

2.4 ± 0.6 |

2.6 ± 0.9# |

|

PAOP mmHg |

19 ± 9 |

16 ± 9 |

14 ± 6#+ |

|

SVRI dyne.sec.cm-5 |

2980 ± 1053 |

2366 ± 966 |

2422 ± 706 |

|

PVRI dyne.sec.cm-5 |

622 ± 389 |

384 ± 230 |

370 ± 267 |

|

EVLW ml/Kg |

10.6 ± 2.1 |

10.6 ± 5.4 |

8.0 ± 2.3 |

|

Six Minute Walk Test m. |

344 ± 51 |

399 ± 67 |

459 ± 81+ |

|

Quality of Life Score |

455 ± 154 |

635 ± 151 |

687 ± 182# # |

|

# p<0.07 ANOVA #+ p = 0.06 # # p < 0.01 ANOVA + p = 0.05 * p < 0.05 ** p £ 0.01 Fishers PLSD compared to baseline PAOP= Pulmonary Artery Occlusion Pressure PVRI= Pulmonary Vascular Resistance Index SVRI= Systemic Vascular Resistance Index EVLW= Extra Vascular Lung Water |

|||

Table 4: Cardiovascular Parameters

|

Plasma Noradrenaline |

Baseline (n=5) |

3 months (n=5) |

12 months (n=4) |

|

Night (0100) nmol/l |

5.8 ± 2.4 |

3.0 ± 1.4* |

1.9 ± 1.6** |

|

Day (1600) nmol/l |

6.0 ± 3.0 |

4.1 ± 1.8 |

3.7 ± 1.5 |

|

* p < 0.05 ** p £ 0.01 Fishers PLSD compared to baseline |

|||

Table 5: Plasma Catecholamine Data.

Data Availability: The data will be made available to other researchers upon reasonable request made in writing to the authors.

Table 4 shows a number of cardiovascular physiology and related variables. Quality of life score improved at 3 months and slightly further at 12 months. Body mass index did not change over that time and although cardiac index improved from 1.7±0.3 to 2.6±0.9 (p<0.07) at 12 months; this was not statistically significant, possibly because of a Type II error. Pulmonary artery occlusion pressure fell from a slightly elevated value of 19±9 mmHg down to a normal value at 14±6 (p<0.07) and there were nonsignificant falls in systemic vascular resistance index and pulmonary vascular resistance index, all compatible with general improvement in cardiac function. Extra vascular lung water (EVLW) fell from 10.6±2.6 to 8±2.3, (normal = 6 to 8ml/kg), but this was not significant.

There were slight increases in arterial CO2 over time from 38±5 mmHg to 41±5 mmHg awake and 40±3 to 42±6 mmHg asleep, these values were not significantly different, although the pattern of slight increase fits with current theories of the aetiology of central sleep apnea [27].

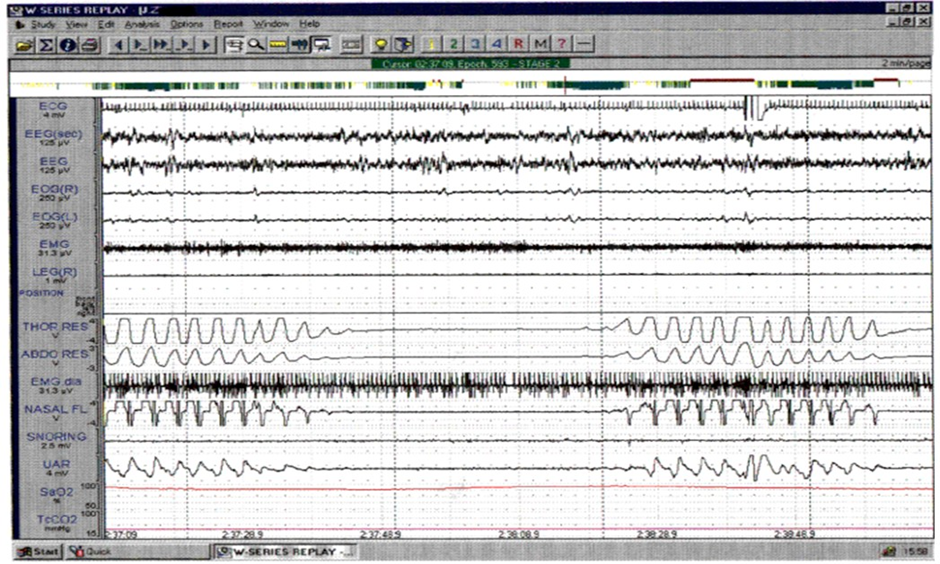

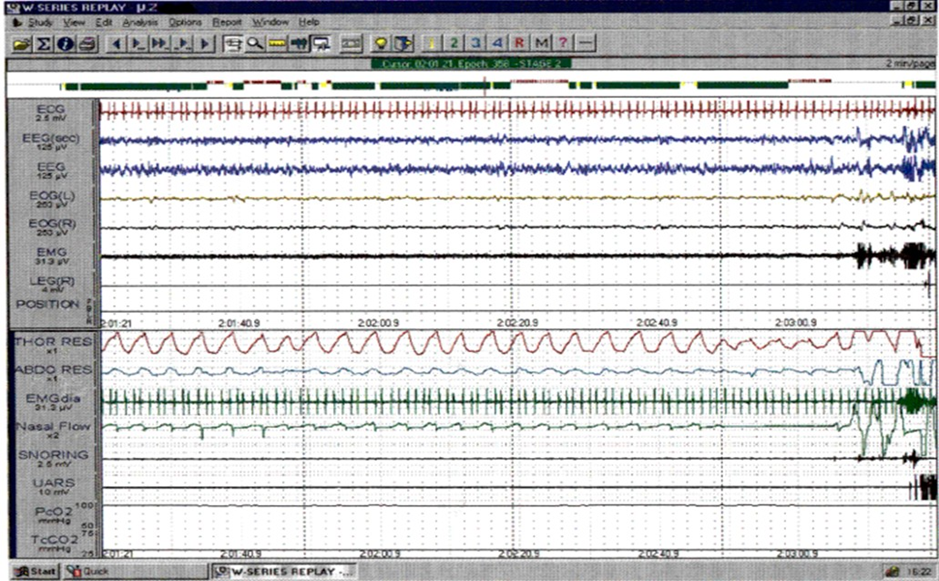

An example of the change in sleep pattern is shown in (Figures 1 and 2). Figure 1 is an example from Subject no. 4 showing a representative 2-minute epoch of Stage 2 non REM sleep before treatment. Figure 2 is the same subject in the same sleep state after 12 months treatment, showing much more regular breathing pattern with the development of an obstructive apnea at the end of the epoch, which is terminated by arousal.

Figure 1: Subject #4 – A representative two-minute epoch from stage 2 NREM sleep at baseline showing CSA. (The “UAR” channel is a surrogate for pleural pressure used in some studies).

Figure 2: Subject #4 – A representative two-minute epoch from stage 2 NREM sleep recorded after 12 months treatment. There is evidence of flow limitation in most breaths on the nasal flow channel, and a clearly obstructive apnea with paradoxical movement of the effort bands, ending with an arousal.

Discussion

These, as yet unpublished studies, were conducted prior to more recent experiments on CSA at high altitude, which have provided additional insights into the interpretation of the results.

Effects on Cardiac Function

The individually titrated CPAP therapy was associated with normalisation of cardiac function over twelve months:

Cardiac index was abnormally low before therapy, improved at three months, and normalised by 12 months. Pulmonary artery occlusion pressure (PAOP) was abnormally high before CPAP therapy, but fell into the normal range after twelve months CPAP therapy.

Associated with those changes were falls in systemic vascular resistance indexed to body surface area (SVRI), which is an objective measure of left ventricular “afterload”. It progressively fell to normal by 12 months.

Extra vascular lung water (EVLW), measured by the double indicator dilution technique [20], was abnormally high before CPAP therapy despite standard medical therapy for heart failure. It normalised between 3 and 12 months of therapy.

The novel EVLW measurements, show objectively what is seen clinically; that heart failure patients with CSA usually have an element of lung congestion.

The improvement in cardiac function parameters was not surprising: Earlier studies in animal models had shown that increased intrathoracic pressure was associated with increased cardiac output [28]. Naughton et al [29] had previously shown in human’s improvements in CSA and heart function by non-invasive techniques, but EVLW had not previously been measured in this context.

Effects on sleep

All subjects showed severe central sleep apnea on their initial diagnostic sleep studies. The obstructive AHI was normal and the minimum oxygen saturation was moderately low. After three months therapy there had been a significant fall in the central AHI. By twelve months this value had fallen further to normal, with a slight increase in minimum saturation and clinically important fall in the arousal index. A fall in the arousal index would explain at least some of the fall in circulating noradrenaline values that was also observed.

The obstructive AHI however had, after three months CPAP therapy, risen from normal to moderate severity obstructive sleep apnea. This reciprocal change in the relationship between central and obstructive events continued over the next nine months, such that after 12 months nasal CPAP therapy, the central events were now normal, but the obstructive events now represented severe obstructive sleep apnea. Although one subject withdrew after 3 months, his central AHI was close to the group average initially, and by 3 months he had developed some OSA. His absence at 12 months was therefore unlikely to have skewed the results, but did weaken the power of the statistical analysis. The mean BMI had not changed, to account for the very dramatic increase in obstructive events.

Sleep architecture, (the proportion of sleep time occupied by the different sleep stages), also changed very dramatically with nasal CPAP therapy. Stage 1 NREM sleep fell by three months and further at twelve months (p < 0.05). Normal is less than 5% so even at twelve months it was still abnormally high (on the nonCPAP test night), but the fall to less than one third of baseline would be regarded clinically as very important.

Stage 2 NREM sleep increased from a low value to a normal value by twelve months (p < 0.01). Stages 3 and 4, (slow wave sleep), were somewhat reduced for age at baseline and did not change substantially over time. REM sleep which usually occupies 1525% of sleep time was abnormally low at baseline, then increased into the normal range by three months (p < 0.05). It remained normal at twelve months. Overall; there was a dramatic shift from light sleep, (Stages 1 and 2), to deeper sleep, (more Stage 2 and REM sleep), with nasal CPAP therapy.

Sleep state is one of the “classical factors” predisposing to CSA. The reduction in Stage 1 sleep with nasal CPAP treatment reduced that propensity to CSA. However Stage 1 sleep remained an abnormally large percentage of sleep time at 13% by twelve months, yet CSA had completely resolved. The change in sleep architecture with nasal CPAP treatment therefore, whilst possibly contributing to the resolution of CSA, was not the only, nor probably the primary cause of the resolution of CSA. It is more likely that the resolution of CSA caused consolidation of sleep and improved sleep architecture by reducing arousals.

Effects on pattern of breathing

A high ventilator response to CO2 in patients with CCF and CSA has been shown by others [3,30]. The resolution of CSA in our subjects over time on CPAP therapy, coincided with a pattern of improvement in measured heart failure indices (CI, SVR1, PAOP, Plasma Noradrenaline) and a slight rise in PaCO2, which would fit with current theories about aetiology of CSA in patients with CCF [7]. Briefly; CCF causes hyperventilation [11] resulting in hypocapnia, which in light sleep induces apnea [27]. Apnea allows brain PCO2 to rise again, initiating hyperventilation, which returns the patient to hypocapnia and another apnea. The documented degree of hypocapnia has been surprisingly minor (4mmHg or less) [10] the mechanism(s) by which CCF causes hyperventilation are uncertain: There are a number of, not mutually exclusive, possible mechanisms:

1. By J receptor stimulation, 2. Due to slow clearance of brain PCO2 due to the low cardiac output, causing an elevated PbCO2. 3. Increased ventilator response to CO2 (the brain produces the CO2/H+ which provides the tonic central respiratory drive [31] 4. Due to an increase in ventilator drive by other means (eg sympathetic activation).

CSA occurs at high altitude in normal subjects by a similar mechanism: At high altitude hypocapnia is driven by a high ventilatory response to hypoxia rather than pulmonary congestion, nevertheless the same hypocapnia/light sleep mechanism causes CSA. This has been shown to be reversed by increasing cerebral blood flow [5,32]. This may well have been the mechanism of improvement in these patients. One would expect cerebral perfusion to improve with improved cardiac output, the effect of which would be to lower the central CO2/H+ drive to ventilation.

Other factors such as moving eupnia away from the apneic threshold because of the rise in PaCO2 or reduced J receptor stimulation due to clearance of extravascular lung water may have also been important.

Of particular interest was the previously unreported development of significant OSA during the same time frame. The reverse effect was previously seen in normal subjects who had mild OSA at sea level, but who then developed severe CSA upon ascent to high altitude [33]. The authors speculated that the high central drive, due to hypoxia, transformed the OSA into CSA by increasing ventilator instability and by stiffening the upper airway. A switch from CSA to OSA has been previously reported in a patient with CCF who changed from severe CSA to OSA after heart transplantation. The author speculated that the “airway instability” associated with OSA predated the CSA [34]. A similar effect has been described by Gold et al with supplemental oxygen therapy [35].

We advance a similar speculation; that the subjects had OSA prior to the development of severe CCF and CSA, and that resolution of the CSA for the reasons outlined above, allowed the pattern of breathing during sleep to return to the previous pattern of OSA, much, as shown in the heart transplant patient [34].

All PSGs were scored by the same experienced registered polysomnographer. Other authors using only chest and abdominal bands to differentiate central from obstructive events found a 0.96 positive predictive value for CSA and 0.98 for OSA [35] compared to scoring using an oesophageal catheter to measure pleural pressure. In our studies, diaphragm surface EMG signals were also used to aid the differentiation of central from obstructive events, so the scoring should have been even more accurate than reported in Gold et al’s study [35].

Effects on quality of life

“Quality of life” was measured by a validated questionnaire [17]. There was both a clinically and statistically significant improvement over three and twelve months that reflected the improvements in sleep quality and walking distance, presumably reflecting improvements in cardiac function. The questionnaire used a number of elements that assess sleep and dyspnoea, which would be positively influenced by successful nasal CPAP therapy in this group. Daytime somnolence, (or energy level), should have also been improved with reduced arousals from sleep.

The six-minute walk test results showed a clinically important, but modest, increase, reflecting normalisation of resting cardiac index at twelve months.

Conclusion

We have shown significant normalization of sleep architecture and resolution of severe CSA by CPAP therapy, at individualized pressures, over a twelve-month period in a small group of patients with severe heart failure. In addition we have observed in the same subjects, the development of severe OSA as the CSA resolved, which has not previously been reported in response to CPAP therapy. This may be clinically important in the management of patients with severe heart failure and CSA. The literature suggests that chronic heart failure will be the next major cardiovascular epidemic [36]. We are likely therefore to see many more patients with severe CCF and CSA [37].

Prescriptions for the provision of positive airway pressure (PAP) to these patients during sleep assume that the CSA will remain constant. Our results, and the experience of others [34], suggest that if PAP improves cardiac function over time, then additional strategies may be required to deal with recurrent, or unmasked, OSA. The level of PAP required is likely to vary over time (and cardiac function) as the degree of CSA and OSA change.

Acknowledgements: We wish to acknowledge with thanks the assistance of Ms Pamela Johnson who scored all the sleep studies, and the assistance of the ICU nursing staff at Manly Hospital during the haemodynamic studies.

The research was performed in the ICU at Manly Hospital. Manly NSW. Australia 2095, and Peninsula Sleep Clinic.

Both authors have seen and approved the manuscript.

These results were not part of a registered clinical trial.

Conflict of Interest: Both authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest (such as honoraria; educational grants; participation in speaker’s bureaus; membership, employment , consultancies, stock ownership, or any other equity interest; and expert testimony or patent licensing arrangements) or nonfinancial interest (such as personal or professional relationships, affiliations, knowledge or beliefs) in the subject matter or materials in this manuscript.

Funding: Sensormedics/ALF Grant in Aid and Northern Sydney Area Health Service grant provided financial support in the form of funding in 1995. Neither sponsor had any role in the design and conduct of this research.

References

- Lofaso F, Verschueren P, Rande JL, Harf A, Goldenberg F (1994) Prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in patients on a heart transplant waiting list. Chest. 106:1689-94.

- Javaheri S, Parker TJ, Wexler L, Michaels SE, Stanberry E, et al. (1995) Occult sleep-disordered breathing in stable congestive heart failure. Ann Intern Med. 122:487-492.

- Agrawal R, Sharafkhanaeh A, Gottlieb DJ, Nowakowski S, Razjouyan J (2023) Mortality Patterns Associated with Central Sleep Apnea among Veterans. A Large Retrospective, Longitudinal Report. Ann. Am Thoracic Soc. 20:450-455.

- Wilcox I, McNamara SG, Dodd MJ, Sullivan CE (1998) Ventilatory control in patients with sleep apnoea and left ventricular dysfunction: comparison of obstructive and central sleep apnoea. Eur Respir J. Jan.11:7-13.

- Naughton MT, Lorenzi-Filho G (2009) Sleep in heart failure. Progress in cardiovascular diseases. 51:339-349.

- Burgess KR, Lucas SJ, Shepherd K, Dawson A, Swart M, et al. (2014) Influence of cerebral blood flow on central sleep apnea at high altitude. Sleep. 37:1679-87.

- Paintal AS (1970) The Mechanism of Excitation of Type J Receptors, and the J Reflex. Ciba Foundation Symposium ‐ Breathing: HeringBreuer Centenary Symposium. 59-76.

- Eckert DJ, Malhotra A, Jordan AS (2009) Mechanisms of apnea. Progress in cardiovascular diseases. 51:313-323.

- Cohn JN, Levine TB, Olivari MT, Garberg V, Lura D, et al. (1984) Plasma Norepinephrine as a Guide to Prognosis in Patients with Chronic Congestive Heart Failure. New England Journal of Medicine. 31: 819-823.

- Bristow MR (1984) The Adrenergic Nervous System in Heart Failure. New England Journal of Medicine. 311:850-851.

- Hanly P, Zuberi N, Gray R (1993) Pathogenesis of Cheyne-Stokes respiration in patients with congestive heart failure. Relationship to arterial PCO2. Chest. 104:1079-84.

- Naughton M, Benard D, Tam A, Rutherford R, Bradley TD (1993) Role of hyperventilation in the pathogenesis of central sleep apneas in patients with congestive heart failure. Am Rev Respir Dis. 148:330338.

- Naughton MT, Benard DC, Liu PP, Rutherford R, Rankin F, et al. (1995) Effects of nasal CPAP on sympathetic activity in patients with heart failure and central sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 152: 473-479.

- Naughton MT, Liu PP, Bernard DC, Goldstein RS, Bradley TD (1995) Treatment of congestive heart failure and Cheyne-Stokes respiration during sleep by continuous positive airway pressure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 151: 92-97.

- Liston R, Deegan P, McCreery C, Costello R, Maurer B, et al. (1995) Haemodynamic effects of nasal continuous positive airway pressure in severe congestive heart failure. European Respiratory Journal 8: 430-435.

- Becker H, Grote L, Ploch T, Schneider H, Stammnitz A, et al. (1995) Intrathoracic pressure changes and cardiovascular effects induced by nCPAP and nBiPAP in sleep apnoea patients. Journal of Sleep Research 4: 125-129.

- Davies RJ, Harrington KJ, Ormerod OJ, Stradling JR (1993) Nasal continuous positive airway pressure in chronic heart failure with sleepdisordered breathing. American Review of Respiratory Disease 147: 630-630.

- Guyatt GH, Bombardier C, Tugwell PX (1986) Measuring diseasespecific quality of life in clinical trials. CMAJ 134: 889-895.

- Guyatt GH, Sullivan MJ, Thompson PJ, Fallen EL, Pugsley SO, et al. (1985) The 6-minute walk: a new measure of exercise capacity in patients with chronic heart failure. Can Med Assoc J 132: 919-23.

- Lipkin DP, Scriven AJ, Crake T, Poole-Wilson PA (1986) Six minute walking test for assessing exercise capacity in chronic heart failure. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 292: 653-655.

- Schuster DP, Calandrino FS (1991) Single versus double indicator dilution measurements of extravascular lung water. Crit Care Med 19: 84-88.

- Pfeiffer UJ, Backus G, Blümel G, Eckart J, Müller P, et al. (1990) A Fiberoptics-Based System for Integrated Monitoring of Cardiac Output, Intrathoracic Blood Volume, Extravascular Lung Water, O2 Saturation, and a-v Differences. Springer Berlin Heidelberg 1990: 114-125.

- Hillman D, Bowes G, Grunstein R, McEvoy R, Pierce R, et al. (1994) Guidelines for respiratory sleep studies. Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand.

- Rechtschaffen AK, Kales AA (1968) A Manual of Standardized Terminol-ogy, Techniques and Scoring System for Sleep Stages of Human Subjects. Service/Brain, LABI, ed) Research Institute, University of California.

- Montserrat JM, Ballester E, Olivi H, et al. (1995) Time-course of stepwise CPAP titration. Behavior of respiratory and neurological variables. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 152: 1854-1849.

- Shoemaker WC (1989) Textbook of critical care. Critical Care Medicine 17: 1087.

- Lang TA, Secic M (2006) How to report statistics in medicine: annotated guidelines for authors, editors, and reviewers. ACP Press.

- Dempsey JA (2005) Crossing the apnoeic threshold: causes and consequences. Exp Physiol 90: 13-24.

- Pinsky MR, Summer WR, Wise RA, Permutt S, Bromberger-Barnea B (1983) Augmentation of cardiac function by elevation of intrathoracic pressure. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol 54: 950-955.

- Naughton MT, Rahman MA, Hara K, Floras JS, Bradley TD (1995) Effect of continuous positive airway pressure on intrathoracic and left ventricular transmural pressures in patients with congestive heart failure. Circulation 91: 1725-1731.

- Solin P, Roebuck T, Johns DP, Walters EH, Naughton MT (2000) Peripheral and central ventilatory responses in central sleep apnea with and without congestive heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 162: 2194-200.

- Ainslie PN, Lucas SJ, Burgess KR (2013) Breathing and sleep at high altitude. Respiratory physiology & neurobiology 188: 233-256.

- Burgess KR, Lucas SJE, Burgess KME, K Sprecher KE, Donnelly J, et al. (2018) Increasing cerebral blood flow reduces the severity of central sleep apnea at high altitude. J Appl Physiol (1985) 124: 13411348.

- Burgess KR, Johnson PL, Edwards N (2004) Central and obstructive sleep apnoea during ascent to high altitude. Respirology 9: 222-229.

- Collop NA (1993) Cheyne-stokes ventilation converting to obstructive sleep apnea following heart transplantation. Chest 104: 1288-1289.

- Gold AR, Bleecker ER, Smith PL (1985) A shift from central and mixed sleep apnea to obstructive sleep apnea resulting from low-flow oxygen. Am Rev Respir Dis 132: 220-223.

- Ziaeian B, Fonarow GC (2016) Epidemiology and aetiology of heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol 13: 368-378.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.