Convergent Mitochondrial and Reward-Circuit Mechanisms Underlying Appetite, Addiction, and GLP-1 Therapeutics

by George B. Stefano¹,²*

¹Department of Psychiatry, First Faculty of Medicine, Charles University and General University Hospital in Prague, Czech Republic

²Mind-Cell LLC, 841 E. Fort Ave, B-411, Baltimore, MD 21230, USA

*Corresponding Author: George B. Stefano, Mind-Cell LLC, 841 E. Fort Ave, B-411, Baltimore, MD 21230, USA

Received Date: 14 January 2026

Accepted Date: 20 January 2026

Published Date: 22 January 2026

Citation: Stefano GB (2026) Convergent Mitochondrial and Reward-Circuit Mechanisms Underlying Appetite, Addiction, and GLP-1 Therapeutics. J Surg 11: 11545 https://doi.org/10.29011/2575-9760.011545

Abstract

Severe appetite dysregulation and substance addiction share conserved neurobiological mechanisms that link reward valuation to cellular energy sensing. Accumulating evidence shows that glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists reduce craving and consumption across multiple substances of abuse, including alcohol and opioids, independent of caloric intake. These effects suggest that addiction and severe appetite represent parallel manifestations of disrupted motivational salience rather than distinct pathologies. At the cellular level, opioids and GLP-1 signaling converge on mitochondrial function and nitric oxide–dependent redox regulation, processes increasingly implicated in neuroadaptation and compulsive reward seeking. Emerging data indicate that GLP-1 receptor agonists stabilize mitochondrial bioenergetics and inflammatory tone, counterbalancing maladaptive states induced by chronic metabolic stress or substance exposure. Framing addiction as a disorder of mitochondrial–reward coupling provides a biologically coherent rationale for repurposing GLP-1–based therapies in substance use disorders and supports mitochondrial-centric models of compulsive behavior.

Keywords: Addiction; GLP-1 receptor agonists; Bioenergetics; Metabolic–reward coupling; Mitochondria; Motivational salience; Nitric oxide signaling; Opioids; Reward circuitry; Semaglutide; Severe appetite dysregulation; Substance use disorders

Opinion

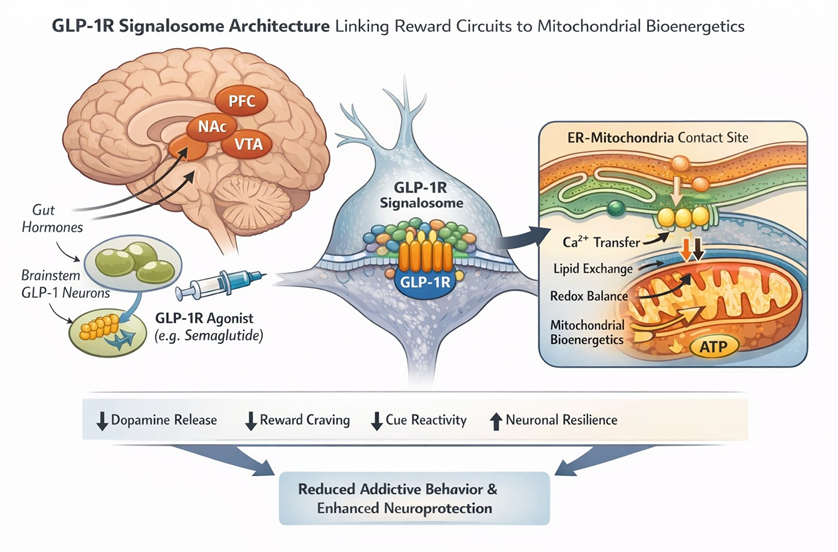

Severe appetite dysregulation, substance addiction, and compulsive reward-seeking behaviors share deeply conserved neurobiological substrates that extend beyond cortical decision-making into cellular bioenergetics and mitochondrial signaling. Emerging clinical evidence indicates that glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, originally developed for obesity and metabolic disease, reduce craving and consumption across multiple substances of abuse, including alcohol and opioids (Figure 1) [1-3]. These effects suggest that “severe appetite” and addiction represent parallel manifestations of dysregulated reward valuation and energy sensing, rather than discrete pathologies. In this context, GLP-1– based therapies may act on an evolutionarily conserved interface linking metabolic state, mitochondrial function, and motivational drive.

Integrating addiction- and reward-circuit–specific GLP-1R evidence into an emerging GLP-1R “signalosome” architecture model further strengthens the mechanistic case that GLP-1 receptor agonists can modulate compulsive reward seeking through spatiotemporally constrained signaling hubs that converge on neuronal excitability, dopamine dynamics, and mitochondrial resilience. In this framework, GLP-1R signaling is organized into nanodomains (“signalosomes”), including at ER–plasma membrane interfaces and at ER–mitochondria contact sites, enabling localized second-messenger kinetics, ion-channel/ transport coupling, and organelle cross-talk that can specify circuit-level outputs [4]. When mapped onto addiction circuitry, this architecture provides a mechanistic substrate for how GLP-1R agonists act within mesolimbic structures-particularly the Ventral Tegmental Area (VTA) and nucleus accumbens/ventral striatumto blunt reward salience and cue-driven motivation (Figure 1)[4].

Preclinical and clinical evidence indicates that GLP-1 signaling also plays a role in the modulation of the mesolimbic reward system, irrespective of food intake. Experimental studies conducted by Egecioglu et al. revealed that GLP-1 receptor agonism decreases alcohol consumption, decreases the activity of the rewarding dopaminergic system, and decreases conditioned place preference for addictive drugs [5-7]. Critically, exendin-4 suppresses accumbal dopamine release while attenuating alcohol-mediated behaviors, directly implicating GLP-1R-dependent modulation of dopaminergic reward signaling [5]. These results were later replicated using human neuroimaging and behavioral studies, demonstrating the impact of GLP-1-based therapies on the response to rewarding cues and the reduction of cravings in human subjects [8-10]. Translationally, GLP1R genetic variation associates with alcohol-related phenotypes and altered reward responsiveness; clinically, exenatide once weekly attenuates alcohol cue reactivity in ventral striatum and reduces dopamine transporter availability (with exploratory benefit in an obesity subgroup), consistent with measurable engagement of reward-circuit neurobiology even when drinking endpoints are heterogeneous [8-9]. Taken together, these results suggest that GLP-1 signaling plays an essential role as the central regulatory component of the salience of motivation, where metabolic satiety and behavioral control interact.

At the cellular level, a unifying mechanism may involve mitochondrial regulation and nitric oxide (NO) signaling. Opioids such as morphine directly interact with mitochondria, stimulating mitochondrial NO release and altering oxidative phosphorylation, redox balance, and energy availability (Figure 1) [11]. These mitochondrial effects occur independently of classical synaptic opioid signaling and suggest that opioids exert part of their reinforcing and dependence-forming actions through intracellular bioenergetic modulation. Disruption of mitochondrial homeostasis is increasingly recognized as a driver of neuroadaptation, tolerance, and compulsive drug seeking, particularly within energy-demanding reward circuits. Recent work extends this mitochondrial framework to GLP-1 receptor agonists. Stefano and colleagues proposed that semaglutide exerts neuroprotective and neuromodulatory effects by stabilizing mitochondrial function, redox signaling, and inflammatory tone, thereby preserving neuronal resilience across degenerative and neuropsychiatric conditions [12]. Within this model, GLP-1 signaling counterbalances maladaptive bioenergetic states induced by chronic metabolic stress or substance exposure. Rather than acting solely through appetite suppression, GLP-1 agonists may restore an evolutionarily conserved equilibrium between mitochondrial energy production and reward valuation (Figure 1).

More recent work spanning 2024–2026 further refines this framework by identifying a convergent interface between GLP-1 receptor agonists, opioid use disorder (OUD), and mitochondrial bioenergetics, reframing addiction and metabolic disease as disorders of cellular energy regulation rather than discrete pathologies [12-16]. GLP-1 receptor agonists have been shown to directly modulate mitochondrial structure and function, restoring membrane potential, improving oxidative phosphorylation efficiency, and reducing reactive oxygen species across metabolically active tissues, including liver, kidney, skeletal muscle, and brain [15,16]. Importantly, GLP-1 analogs cross the blood–brain barrier, where they enhance mitochondrial resilience within mesolimbic and cortical circuits implicated in reward processing, stress responsivity, and neurodegeneration [16]. Endogenous morphine is present across phylogeny in both invertebrates and vertebrates and functions as an evolutionarily conserved signaling molecule that downregulates physiological stress responses, particularly within immune and neuroimmune systems, including immune elements of the central nervous system [17]. Crucially, endogenous morphine exhibits dual signaling properties, acting locally as a neurotransmitter while also functioning systemically as a hormone, as evidenced by its presence in circulating blood. These effects are mediated in part by μ-opioid receptor subtypes selectively coupled to nitric oxide signaling, thereby linking endogenous opioid activity directly to mitochondrial redox regulation and cellular energy homeostasis.

A closely analogous signaling logic is now evident for glucagonlike peptide-1 (GLP-1) and its long-acting analog semaglutide. Although classically categorized as a peripheral metabolic hormone, GLP-1 signaling also operates centrally as a neuromodulatory system, influencing reward valuation, motivational salience, and behavioral restraint [12]. Like endogenous morphine, semaglutide therefore functions as a dual-mode regulator, integrating endocrine signaling with direct central nervous system actions. Emerging evidence demonstrates that semaglutide exerts direct mitochondrial effects, including restoration of mitochondrial membrane potential, improvement of oxidative phosphorylation efficiency, and suppression of oxidative stress within metabolically active tissues and brain circuits implicated in addiction and neurodegeneration [12-16]. In the signalosome view, mesolimbic GLP-1R signaling can be conceptualized as subcellular “routing” that couples motivational drive to bioenergetic state through ER–mitochondria contact-site nanodomains positioned to regulate calcium transfer, lipid signaling, and mitochondrial stress buffering-thereby influencing neuronal firing thresholds and dopamine release probability in reward-relevant neurons [4].

On the other hand, chronic opioid use has been universally associated with mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and dysregulated inflammatory and nitric oxide signaling, culminating in the development of neuropathic pain, metabolic dysfunction, as well as the reinforcement of addictive behaviors [11,18]. Also, clinical evidence has indicated the potential use of GLP-1 receptor agonists for the attenuation of opioid-related harm, as measured by a decrease in the incidence of opioid overdose as well as a decrease in opioid craving and seeking behaviors (Figure 1) [1-3]. On-going clinical trials involving the use of semaglutide, a GLP-1 receptor agonist, among patients already diagnosed with established OUD, have suggested that stabilization of the mitochondria as well as metabolic function can normalize reward value, sleep, as well as relapse risk [1]. Clinical observations increasingly align with this hypothesis. Controlled and observational studies report reductions in alcohol intake, craving intensity, and relapse risk among individuals treated with GLP-1 receptor agonists [2,3,19]. Importantly, these effects are observed without substitution of one addictive behavior for another, supporting a central normalization of reward processing rather than nonspecific behavioral suppression. The convergence of metabolic, mitochondrial, and motivational pathways suggests that addiction and severe appetite dysregulation may be viewed as disorders of bioenergetic signaling, with mitochondria serving as a shared intracellular target. Most recently, a randomized clinical trial reported that low-dose onceweekly semaglutide reduced laboratory alcohol self-administration and significantly reduced weekly alcohol craving (with additional signal for reduced cigarettes/day in current smokers), reinforcing that GLP-1R agonists can dampen compulsive reinforcement across substances in at least some clinical contexts [1].

Figure 1: Conceptual schematic of convergent GLP-1R reward-circuit signaling and mitochondrial mechanisms in appetite dysregulation and addiction. The figure integrates (i) GLP-1R “signalosome” nanodomain organization, including ER–plasma membrane and ER– mitochondria contact-site hubs that can constrain second-messenger kinetics and couple ion-channel/transport processes to organelle cross-talk [4]; (ii) mesolimbic circuit targets (VTA → nucleus accumbens/ventral striatum) in which GLP-1R agonism can reduce cue reactivity and dampen reward salience with measurable dopaminergic signatures (e.g., altered accumbal dopamine signaling and dopamine transporter availability) [5,8-10]; and (iii) mitochondrial convergence mechanisms in which opioids stimulate mitochondrial nitric oxide biology and redox/energetic shifts [11], while semaglutide/GLP-1R agonism stabilizes mitochondrial function, oxidative phosphorylation efficiency, and inflammatory tone, supporting neuronal resilience and bioenergetic recalibration across reward-relevant circuits [12,15-16]. Abbreviations: Prefrontal Cortex (PFC), Nucleus Accumbens (NAc); Ventral Tegmental Area (VTA).

Despite growing enthusiasm for a unifying GLP-1–mitochondrial framework, several peer-reviewed studies temper or challenge key elements of this hypothesis. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of exenatide in alcohol use disorder failed to meet its primary endpoint, with efficacy signals limited to individuals with obesity, suggesting metabolic status as a critical moderator [9]. Preclinical studies further reported that GLP-1 receptor agonist treatment did not reduce opioid self-administration or conditioned place preference, arguing against a uniform anti-addiction effect [20]. Mechanistic reviews caution that some reductions in intake may reflect nonspecific effects such as nausea or altered satiety rather than selective modulation of reward valuation [21]. Recent syntheses reiterate that human evidence remains heterogeneous and context-dependent [22]. Systematic synthesis likewise emphasizes limited high-quality randomized evidence overall, while still identifying specific signals (including neuroimaging cue-reactivity effects and obesity-stratified improvements) that motivate targeted mechanistic trials aligned to circuit- and metabolic-phenotype stratification. Framed this way, addiction phenotypes become testable outputs of GLP-1R signalosome topology and mitochondrial state control-a unified, evolutionconsistent explanation that is experimentally tractable at the levels of nanodomain assembly, dopamine-circuit physiology, and mitochondrial energetics [4,10,12,23-25].

Conclusion

Converging preclinical, clinical, and mechanistic evidence supports an integrative framework in which severe appetite dysregulation and substance addiction reflect maladaptive coupling between mitochondrial bioenergetics, nitric oxide– dependent redox signaling, and reward circuitry. GLP-1 receptor agonists emerge as modulators of an evolutionarily conserved interface linking metabolic state to motivational salience. At the same time, counter-evidence highlights important limitations, including metabolic state dependence, substance specificity, and unresolved mechanistic questions. Viewed in this light, GLP-1– based interventions represent a compelling but conditional test case for broader bioenergetic models of compulsive behavior.

Author Contributions: Single author

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate: Not applicable.

Acknowledgment: ChatGPT 5.2 was used for information organization and figure generation.

Funding: This research received no external funding.

Conflict of Interest: The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Hendershot CS, Bremmer MP, Paladino MB, et al. (2025) Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adults With Alcohol Use Disorder: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry 82: 395-405.

- Farokhnia M (2022) Effects of GLP-1 receptor agonism on alcohol use disorder. Addict Biol 27: e13211.

- Lengsfeld S, et al. (2023) GLP-1 receptor agonists and substance use outcomes. E Clinical Medicine 57: 101865.

- Austin G, Tomas A (2026) Signaling architecture of the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor. J Clin Invest 136: e194752.

- Egecioglu E, Steensland P, Fredriksson I, Feltmann K, Engel JA, et al. (2013) The glucagon-like peptide 1 analogue Exendin-4 attenuates alcohol mediated behaviors in rodents. Psychoneuroendocrinology 38: 1259-1270.

- Egecioglu E, Engel JA, Jerlhag E (2013) GLP-1 receptor activation suppresses alcohol reward. PLoS One 8: e77284.

- Vallöf D, et al. (2015) GLP-1 receptor activation attenuates drug reward. Addict Biol 21: 422-437.

- Suchankova P, Yan J, Schwandt ML, et al. (2015) The glucagonlike peptide-1 receptor as a potential treatment target in alcohol use disorder: evidence from human genetic association studies and a mouse model of alcohol dependence. Transl Psychiatry 5: e583.

- Klausen MK, Jensen ME, Møller M, et al. (2022) Exenatide once weekly for alcohol use disorder investigated in a randomized, placebocontrolled clinical trial. JCI Insight 7: e159863.

- Jerlhag E (2025) GLP-1 receptor agonists as promising therapeutic targets for alcohol use disorder. Endocrinology 2025: 166.

- Stefano GB, Mantione KJ, Capellan L, et al. (2015) Morphine stimulates nitric oxide release in human mitochondria. J Bioenerg Biomembr 47: 409-417.

- Stefano GB, Büttiker P, Weissenberger S, Raboch J, Anders M (2025) Semaglutide and the pathogenesis of progressive neurodegenerative disease: The central role of mitochondria. Front Neuroendocrinol 79: 101217.

- Drucker DJ (2018) Mechanisms of action and therapeutic application of glucagon-like peptide-1. Cell Metab 27: 740-756.

- Nauck MA, Meier JJ (2019) Incretin hormones: Their role in health and disease. Diabetes Obes Metab 21: 5-21.

- Lee CJ, et al. (2023) GLP-1 receptor agonists and mitochondrial function in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 72: 1234-1245.

- Hölscher C (2014) Central effects of GLP-1: New opportunities for treatments of neurodegenerative diseases. J Endocrinol 221: T31T41.

- Stefano GB, Goumon Y, Casares F, et al. (2000) Endogenous morphine. Trends Neurosci 23: 436-442.

- Li YZ (2021) Opioid-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and neurotoxicity. Neuroscience 452: 26-38.

- Freet CS (2025) GLP-1 receptor agonists in substance use disorders. Addict Sci Clin Pract 20: 89.

- Bornebusch AB, Fink-Jensen A, Wörtwein G, Seeley RJ, Thomsen M (2019) Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist treatment does not reduce abuse-related effects of opioid drugs. eNeuro. 2019.

- Skibicka KP (2013) The central GLP-1: Implications for food and drug reward. Front Neurosci 7: 181.

- Klausen MK, Knudsen GM, Vilsbøll T, Fink-Jensen A (2025) Effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists in alcohol use disorder. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 136: e70004.

- Subhani M, Dhanda A, King JA, et al. (2024) Association between glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists use and change in alcohol consumption: a systematic review. EClinicalMedicine 78: 102920.

- Farr OM, Upadhyay J, Rutagengwa C, et al. (2016) Effects of GLP-1 on brain activation during food reward processing. Diabetes Care 39: 220-228.

- Badulescu S (2025) Semaglutide for the treatment of cognitive dysfunction in major depressive disorder: A randomized clinical trial. Med 2025: 100916.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.