Contractility Assessment of Gut Tissues from Hirschsprung and Primary PIPO: A Pilot Study

by Michela Pitto1,3, Cristiana Picco1*, Alessandro Barbin1, Maria Grazia Faticato2 ,Raffaella Barbieri1, Jacopo Ferro2, Girolamo Mattioli2,3, Giuseppe Santamaria2, Pasquale Striano2,3, Raffaella Magrassi1, Francesco Beltrame Quattrocchi4,5, Paolo Gandullia2, Isabella Ceccherini2, Federica Viti1

1Institute of Biophysics, National Research Council, Genova, Italy

2IRCCS Istituto Giannina Gaslini, Genova, Italy

3DINOGMI, University of Genova, Italy

4DIBRIS, University of Genova, Italy

5National Institution of Italy for Standardization Research and Promotion, Palermo, 13 Italy

*Corresponding Author: Cristiana Picco, Institute of Biophysics, National Research Council, Genova, Italy

Received Date: 18 December 2025

Accepted Date: 29 December 2025

Published Date: 02 January 2026

Citation: Pitto M, Picco C, Barbin A, Faticato MG, Barbieri R, et al. (2025) Contractility Assessment of Gut Tissues from Hirschsprung and Primary PIPO: a Pilot Study. J Dig Dis Hepatol 10 : 234. https://doi.org/10.29011/2574-3511.100234

Abstract

Background: Primary chronic intestinal pseudo-obstructions and Hirschsprung disease are rare genetic diseases recognized as severe intestinal dysmotility pathologies. These monogenic disorders, with prenatal or neonatal onset in the most severe forms, are characterized by gut contraction impairments, which lead to recurrent intestinal pseudo-obstructions. The aim of this pilot work is to quantify the contraction ability of ex-vivo gut tissues affected with these pathologies. Methods: A dynamometric system was implemented ex-novo to measure changes in the force and displacement exerted by intestinal samples during contraction pharmacologically induced with carbachol. Contractile properties were assessed in human intestinal tissues collected from pediatric/ young adult patients diagnosed with genetic primary chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction or Hirschsprung disease. The control group consisted of patients with intestinal diseases other than primary chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction and Hirschsprung disease, who had neved had intestinal contraction problems. To assess the homogeneity of the control population different parameters (sex, age, tissue preservation and intestinal tract) were evaluated. Based on these results, comparisons between case and control populations were performed. Results: Gut muscles from pediatric controls exert similar forces independently of age, sex, intestinal tract (either colon or ileum) and preservation mode. The main outcome demonstrated that gut muscles from patients affected with genetic primary chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction and Hirschsprung disease display significantly reduced contractile activity compared with controls. Conclusions: This study aims to improve knowledge of these diseases, providing quantitative data about intestinal smooth muscle contraction. In perspective, this approach might be exploited to support the screening of promising therapeutic molecules.

Keywords: Gut tissue contraction; Intestinal dysmotility; Isometric and Isotonic sensors.

Introduction

Gut tissue is composed of several layers, including the enteric nervous system (ENS) and two muscle layers (the inner circular and the outer longitudinal layers). Impairments in the structure or function of the ENS or the SIP syncytium (constituted by Smooth muscle cells - SMC, Interstitial cells of Cajal - ICC, and Plateletderived growth factor receptor α-positive cells - PDGFRα+) affect gut motility, causing nutritional and digestive dysfunctions. Muscle tissue is composed of intestinal SMC, which are spindle-shaped myocytes, where myosin is the molecular motor that allows the acto-myosin complex to slide (through displacement of the myosin head on actin by ATP hydrolysis) and shorten during contractile activity [1].

Pediatric intestinal pseudo-obstructions (from now on referred to as ‘PIPO’) [2] and Hirschsprung disease (from now on referred to as ‘HSCR’) [2] are considered the most severe chronic primary intestinal dysmotility of the pediatric age. Citing Thapar et al. [2], “PIPO is a disorder characterized by the chronic inability of the gastrointestinal tract to propel its contents, mimicking mechanical obstruction in the absence of any lesion occluding the gut, with persistence of symptoms for 2 months from birth or at least 6 months thereafter. It is regarded as the most severe end of a spectrum of gut motility disorders comprising a heterogeneous group of conditions affecting the structure and/or function of components of the intestinal neuromusculature”. In particular, the present paper refers to genetic primary PIPO, an umbrella of rare conditions where chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction is the primary symptom (not secondary to other pathologies, nor idiopathic) and is caused by an ascertained genetic driver. Defects in the enteric smooth muscle, enteric nervous system, mitochondria, or cells of Cajal can result in a dramatic reduction in peristalsis, which causes recurrent intestinal pseudo-obstruction and leads to several hospitalizations and surgical interventions. Depending on the affected component of the intestinal structure or on genetic information, primary PIPO can be classified as ‘myogenic’, ‘neurogenic’, ‘mitochondrial’ or ‘mesenchymal’ [3]. PIPO diagnostic process can be difficult, especially when no clear genetic driver associated with the clinical condition is identified in patients.

Moreover, the lack of ascertained causative molecular mechanisms underlying PIPO onset is preventing the identification of useful pharmacological therapies. Excluding intestinal transplant (which is now mostly discouraged), no treatment exists for PIPO: the only management strategy consists of the implementation of total parenteral nutrition and decompressing ostomies, exposing patients to the constant risk for infection, kidney failure and nutritional imbalance [3]. Hirschsprung disease (HSCR), also known as congenital aganglionic megacolon, is another rare congenital condition impacting on the gut. It is a neurocristopathy, characterized by the absence of enteric ganglion cells in both the submucosal (Meissner) and myenteric (Auerbach) plexuses in a distal segment of the gastrointestinal tract. This aganglionosis results in tonic contraction of the affected bowel, which is unable to relax and prevents the passage of stool, thus causing megacolon and functional intestinal obstruction. HSCR is a genetically complex disorder, with both monogenic and polygenic influences. The RET proto-oncogene is the principal contributor [4], whereas other possibly implicated genes include SOX10, EDNRB, EDN3, GDNF, NRTN, and L1CAM. HSCR classification, based on the extent of aganglionosis from the anus upward, includes ‘ultrashort segment’ [5], ‘short-segment’ [6], ‘long-segment’ [7], ‘total colonic aganglionosis’ [8], and ‘total intestinal aganglionosis [9]. Affected patients present with severe constipation and abdominal distension, which require surgical removal of the pathological segments of the distal bowel. This remains the only possible treatment currently available for HSCR disease.

In this scenario of extremely rare and orphan motility disorders, the identification of suitable models of pathology and functional assays can support advances in the understanding of the disease and improvements in diagnostic approaches, and foster the identification of new potentially effective therapies. In particular, affected gut tissues, which intrinsically recapitulate the 3D features of the disease, can represent useful models of pathology, especially if coupled to functional readouts, adequate for the disease. In the context of such rare dysmotility pathologies, the functional endpoint for tissue evaluation is the contraction ability.Examples of ex vivo gut muscle tissue contractility quantification exist in literature, regarding murine and human models. Bautista et al. [10] analyzed ileal segments of homozygote knockout Piezo1ΔSMC mice mounted on a multi-wire myograph, revealing contractile patterns characterized by reduced amplitude, altered duration, and increased irregularity in intervals, compared to controls. In TβRIIΔk-fib transgenic mice, characterized by ligand-dependent upregulation of TGF-β signaling, colonic fibrosis is associated with diminished colonic strip contractility, in organ-bath experiments following carbachol stimulation [11]. Smooth muscle contraction analysis allowed to observe that in human urinary bladder age-dependent Rho kinase activity plays a key role in mediating carbachol-induced contraction [12]. Also, investigation of HSCR gut samples has been carried out [13], demonstrating that intestinal tissues from patients affected with HSCR exhibit significantly reduced acetylcholineinduced contractility compared with other gut malformations. Similar studies have assessed contractility in gut tissue segments from adult, generic – non genetically assessed, nor primary - CIPO [14], where colonic smooth muscle function was evaluated using classical isometric organ-bath assays, after equilibration under resting tension, and pharmacological stimulation with agents such as KCl and carbachol. Tests showed a markedly reduced contractile tissue ability in CIPO tissues compare to cancer controls.

These works highlight how ex vivo studies of gut segments can provide mechanistic insights into disease-related changes in motility, and provided the inspiration for profitably extending the ex vivo tissue contraction evaluation to the functional assessment of primary genetic PIPO, employing a dual-sensor system to provide the full characterization of the contraction activity. To this end, a low-cost custom dynamometric system, inspired by literature [15] and developed ad-hoc for this study, was implemented. Relying on this tool, the present pilot work aims to quantify force and displacement parameters during the contraction of ex vivo human intestinal tissues from pediatric/young adult patients affected with genetic primary PIPO or HSCR, compared to controls. The impact of the proposed pilot study is double. The primary aspect regards providing additional knowledge on this poorly known and often understudied group of diseases by quantifying the functional impairment on tissue contraction. Especially for PIPO, this study aims to contribute to fill the gap between knowledge about organ dysfunction (which is clinically recognized [2] and quantified through antroduodenal manometry (ADM) [16] and the impairment quantified at the cellular level [17]. This might be useful to reinforce the diagnostic path, on one side, particularly in the absence of a clear genetic driver of the disease. On the other side, given the lack of pharmacological therapies for such disorders, the proposed approach may support the future screening, in human pre-clinical samples, of promising new therapeutic approaches.

Methods

Experimental setup

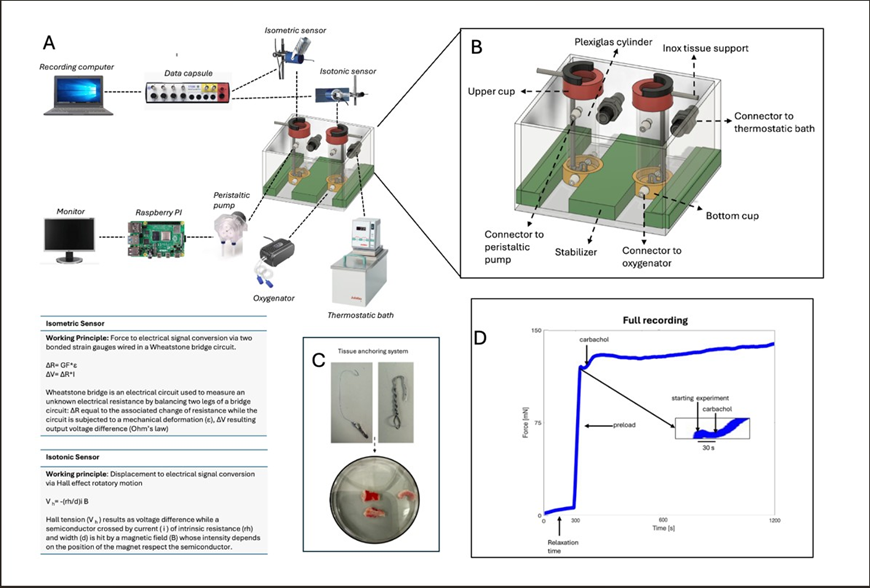

A new setup was custom-built, drawing conceptual and technical inspiration from literature [15]. The dynamometric system included an isometric sensor (7004, Ugo Basile, Gemonio, VA, Italy), which is able to measure the force exerted by the tissue during its contractile activity (operating range: 0-10 g), and an isotonic sensor (7006, Ugo Basile, Gemonio, VA, Italy), which is able to measure tissue displacement (operating range: 15° about the centre). Data capsule Evo (17308, Ugo Basile), which converts analogical to digital data (resolution 16 bit per channel), was coupled to sensors and connected to a recording workstation equipped with Labscribe4 (Ugo Basile). The working principles and a schema of the whole setup are reported in (Fig 1A). A homemade polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) bath chamber was developed to accommodate tissues (Fig 1B). Two connectors for each cylinder allow chamber filling: medium flux is regulated by two peristaltic pumps controlled by an ad hoc Python routine running on Raspberry PI. An oxygenator and a thermostatic bath (to maintain the water in the bath chamber at 37°C) are used to keep the tissue viable throughout the experimental phases.

Patient recruitment, tissue preparation and stimulation protocol

The cohort of patients affected with intestinal dysmotility (named ‘IntD’) includes paediatric and young adult patients affected with primary genetic PIPO (2 patients, ileum and colon) or HSCR (3 patients: for 2 patients, colon; for 1 patient, ileum and colon). The control cohort (named ‘Ctrl’) includes patients affected with pathologies different from primary genetic PIPO or HSCR, with no episodes of secondary intestinal pseudo-obstruction in their life. It consisted of 2 cases of necrotizing enterocolitis (for both, ileum and colon), 6 cases of inflammatory bowel diseases (for 3 subjects, ileum and colon; for 3 subjects, ileum), 2 cases of intestinal perforation (for 1 patient, ileum; for 1 patient, both ileum and colon), 1 case of peritonitis (ileum), 1 case of appendicitis (ileum), and 1 case of trisomy 19 (ileum). Human tissue samples were collected at the IRCCS Istituto Giannina Gaslini Pediatric Hospital in Genova (Italy). Sampling was performed when a surgical procedure was necessary for patients, without any detriment for donor subjects (approved ethics protocol: N. CET - Liguria: 244/2024 - DB id 13938). Most tissues are collected during elective surgery, zwhen performing ostomies, anastomoses or corrective/reconstructive interventions.

Each resected sample undergoes a standardized procedure. Sample is put in a tube (50 ml) containing 20 ml of RPMI culture medium with 10% FBS, 2 mM L-Glutamine, 2 ml Penicillin-Streptomycin solution (100x) and transferred to the laboratory, where the intestinal ring is placed in oxygenated Krebs solution (in mM: 117 NaCl, 4.6 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.2 MgSO4, 1 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 10 HEPES, 11 D-glucose) open vertically and epithelial and adipose layers are removed. The tissue is cut longitudinally into pieces of selected sample size (length approximately 1 cm, thickness approximately 3 mm) and either processed immediately (fresh tissue) or stored at –80 °C in vials containing a solution of 90% serum and 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (frozen tissue). In the latter case, tissues are defrosted just before performing tests. Upon thawing, tissues are placed in oxygenated Krebs solution. Waiting for being tested, pieces are preserved in a petri dish containing cold, oxygenated Krebs solution, and stored in fridge. Tissues are processed and measured within 3 hours from their arrival in the laboratory.

By means of a hook puncturing the bottom side of the tissue and a spring clip to secure it at the upper end (Fig. 1C), each tissue was accommodated in the bath chamber in a vertical configuration, thus enabling the measurement of sample contraction along the longitudinal muscle. Surgical threads (HS6822 Ethicon; polypropylene; needle length: 26 mm, needle curvature 1/2, needle gauge: 3.0) were used to connect the tissues to the sensors. Polypropylene is a non-absorbable monofilament with minimal stretch, thus offering strength and stability.

Initially, the bath chambers are filled with Krebs solution to mimic the human body environment. and Length adaptation and preload was necessary to adjust isotonic and isometric sensors to each specimen, to keep the thread taut in the organ bath, thus ensuring minimal mechanical stress and maintaining the tissue close to its physiological resting state. Preload ranged from 1 to 1.5 g (depending on tissue weight), while the initial tissue length spanned between 5 and 10 mm (according to sample size). In this tissue relaxed condition, the baseline signal is recorded for 5 minutes (Fig.1D). Carbachol (CCh) 50 (prepared immediately before use) is added, to pharmacologically induce tissue contraction. Dose was selected as the saturation concentration, based on literature [12]. Tissue response is recorded for 20 minutes, inferred from the literature as an adequate time frame for tissue contraction [12] (Figure 1A-1D).

Figure 1: (A) Dynamometric setup schema. Setup components are described, together with the working principles of the sensors. (B) Prototype (realized with Fusion 360 software) of the developed homemade polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) bath chamber, to accommodate tissues. Two connectors for each cylinder allow filling: medium flux is regulated by two peristaltic pumps controlled by an ad hoc Python routine running on Raspberry PI. An oxygenator and a thermostatic bath (to maintain the water in the bath chamber at 37°C) kept the tissue viable throughout the experimental phases. PMMA cylinders: tightly connected to the base via magnetic blockage and stabilizers; bottom cup: drilled on both sides facilitating fluid and oxygen passage connectors to the oxygenator; upper cup: integrated with magnets to stabilize the inox tissue support; and connectors to the thermostatic bath: to maintain a temperature of 37°C. (C) Anchoring system for anchoring the gut open-ring pieces, comprising a spring clip, bottom hook and surgical thread to maintain the tissue in a vertical configuration. (D) Typical acquired signal, including 5 mins of baseline (relaxation time), preload, starting experiment with carbachol (cch) administration and 20 mins of contraction activity.

Experimental design

To evaluate gut tissue contraction, force, displacement, and speed were retrieved from the isometric and isotonic sensors of the system. The first set of evaluations aimed to assess the homogeneity of the control population. In particular, patients’ sex (female/male) and age (infant-child: 0-8 years; adolescent: 8-17 years), sample preservation mode (frozen/fresh), and intestinal tract (ileum/colon, given the known difference in their stiffness [18, 19]) were considered. Results from this analysis guided the successive comparison between Ctrl and IntD data distributions.

Data acquisition, analysis and statistics

Each sample was characterized by the following metadata: subjects’ clinical and demographic features (age, sex and disease), intestinal segment under analysis, and sample preservation method (fresh or frozen). Isotonic or isometric responses were recorded for each sample as voltage output signals and translated into displacement (D) and force (F) values respectively, through a twopoint calibration process. In brief, the isometric sensor employs two weights (0 and 5 g), which are associated with the respective voltage outputs in the acquisition system; in the isotonic case, the sensor displacements (0 and 5 mm) are leveraged and associated with the voltage outputs. Starting from the known values, the calibration process establishes a linear relationship between the dependent variables y (F and D) and the independent variable x (the voltage output, Vout) following the relation y=a*x+b. Calibration is performed once before a set of acquisitions. Data conditioning and plotting were performed in the MATLAB environment. To minimize noise, data were smoothed via a Gaussian window moving along the signal (width of 700 samples). Signal was shifted to a baseline, where the minimum value was 0. Under these conditions, the following parameters were extracted during sample contraction: force, F=Fmax, from the isometric sensor; displacement, calculated in mm and plotted as the percentage of variation of tissue length, L: D%=D*100/L; and contraction speed, S=ΔD/ΔT, obtained by processing data from the isotonic sensor (T = time). The Kolmogorov‒Smirnov test was applied to verify the normality of the datasets, and the statistical significance of nonparametric distributions was calculated via the Mann‒ Whitney test. Nonparametric data are presented as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs). In the plots, ‘N’ indicates the number of independent patients, and ‘R’ represents the total number of analysed samples.

Results

Recruited patients

Overall, 13 subjects were included in the Ctrl population. The ‘IntD’ cohort included 1 myogenic (ACTG2R257C) and 1 mitochondrial (LIG3) PIPO case, and 3 HSCR patients (Table 1). Samples were collected when patients underwent ‘ostomy’ surgery in the presence of PIPO, and ‘corrective surgery’ in the presence of HSCR disease. Samples from PIPO patients come from the bowel and colonic tract. Samples from HSCR cases derive from the aganglionic gut segment. Images of tissue staining from the recruited patients provide information about the studied specimen (Supplemental Figs. S1–S15).

Samples composing the Ctrl group were collected in conjunction with necessary surgery, in particular: NEC and intestinal perforation affected patients underwent anastomosis; IBD and trisomy 19 affected patients underwent standard resection/ostomy focused on the impaired intestinal tract; immunodeficiency, peritonitis, and appendicitis affected patients underwent ileostomy (Table 1).

# | Type | Age | Sex | Disease | Segment | Surgery | Type |

Cases (IntD population) | |||||||

1 | HSCR | 6 months | M | Hirschsprung’s Disease, negative to RET, short-segment HSCR form aganglionosis extended to rectum-sigmoid colon | Colon | Elective surgery | Ileocolectomy and ileostomy revision |

2 | 1 year | F | Hirschsprung’s Disease,negative to RET longsegment HSCR form aganglionosis extended to transverse colon | Colon | Elective Surgery | subtotal colectomy and ileosigmoid anastomosis | |

3 | 3 years | F | Hirschsprung’s Disease, negative to RET, shortsegment HSCR form, aganglionosis extended to rectum-sigmoid colon | Colon | Elective surgery | Ileocecal resection and ileocolic anastomosis | |

4 | CIPO | 3 years | F | VSCM ACTG2R257C | Ileum & Colon | Emergency surgery | lleocolectomy and ileostomy re-creation |

5 | 22 years | M | Mitochondrial CIPO LIG3 | Ileum & Colon | Elective surgery | en Bloc Ileocecal resection | |

Controls (Ctrl population) | |||||||

6 | 3 months | M | Necrotizing enterocolitis | Ileum & Colon | Elective Surgery | Ileo-sigmoid anastomosis with near-total colectomy | |

7 | 3 months | M | Necrotizing enterocolitis | Ileum & Colon | Elective surgery | en Bloc Ileocecal resection | |

8 | 4 months | F | Immunodeficiency | Ileum & Colon | Elective surgery (ileum) Emergency surgery (colon) | ileostomy | |

9 | 7 years | M | Crohn’s Disease | Ileum & Colon | Elective surgery | resection of the ileocecal block | |

10 | 15 years | F | Crohn’s Disease | Ileum | Elective surgery | ileo-sigmoid anastomosis | |

11 | 16 years | M | Crohn’s Disease | Ileum | Elective surgery | resection of the ileocecal block | |

12 | 17 years | M | Crohn’s Disease | Ileum | Elective surgery | ileo-sigmoid anastomosis | |

13 | 15 years | F | Ulcerative Colitis | Ileum & Colon | Elective surgery | colectomy and ileostomy | |

14 | 2 years | F | Trisomy 19 | Ileum | Elective surgery | ileal resection | |

15 | 2 years | M | Intestinal perforation | Ileum | Emergency surgery | ileo-sigmoid anastomosis | |

16 | 3 years | M | Intestinal perforation | Ileum & Colon | Elective surgery | ileo-sigmoid anastomosis | |

17 | 12 years | F | Peritonitis | Ileum | Emergency surgery | ileostomy | |

18 | 12 years | F | Appendicitis | Ileum | Elective surgery | ileostomy | |

For each patient, the number of samples tested ranged from 2-5, depending on the dimension of the initial available tissue.

Homogeneity of the control population

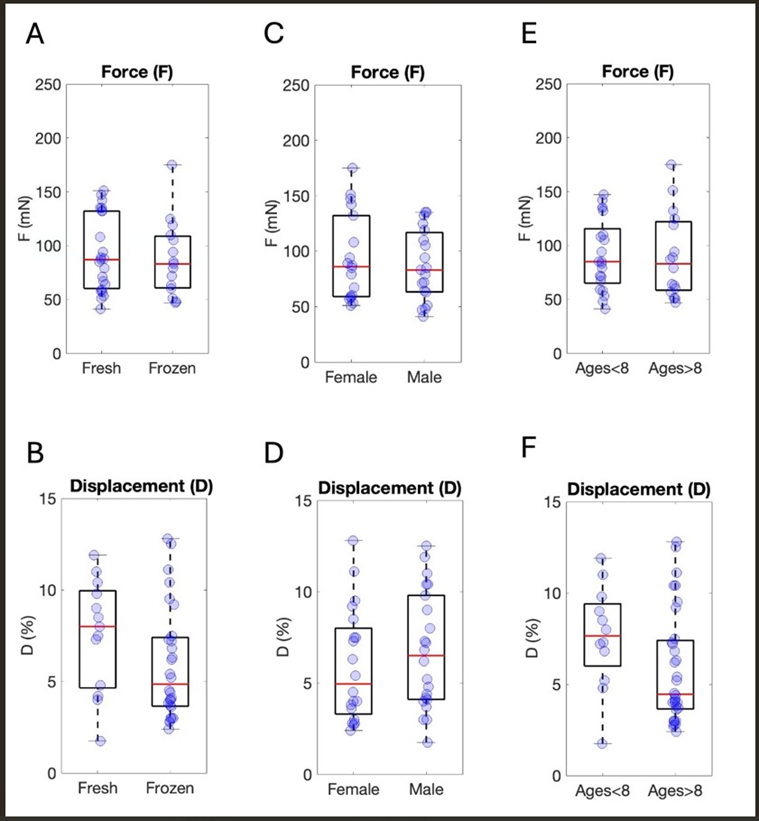

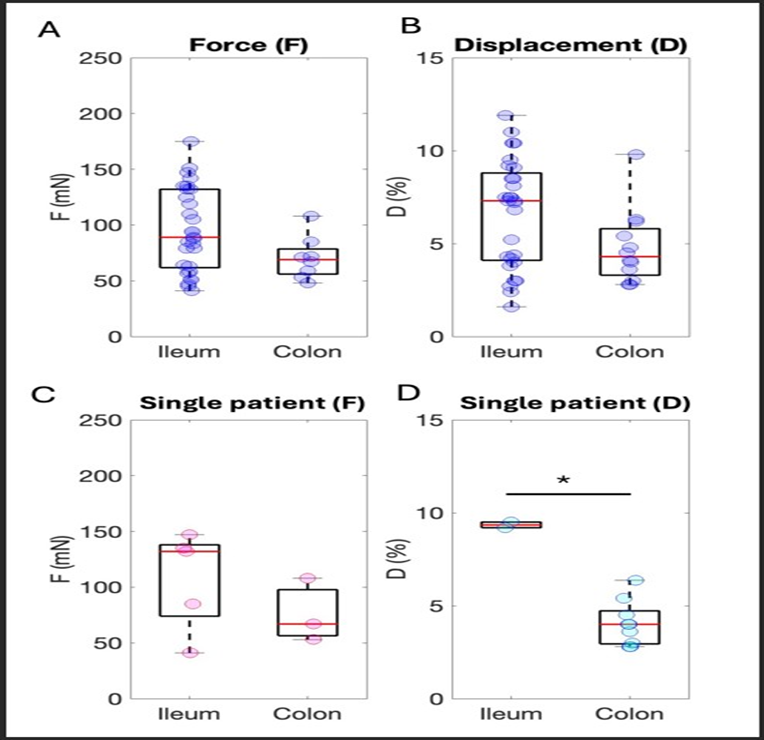

Ctrl population was tested to evaluate its homogeneity and to assess whether sample-specific parameters impacted the tissue contractile outcome. The comparison between fresh and frozen control samples revealed no statistically significant differences in tissue performance in both isometric (pValueisom=0.62) and isotonic (pValueisot=0.071) evaluations (Fig. 2A,B). Analogously, no influence of patient sex (Fig. 2C,D) and age (Fig. 2E,F) on sample contraction emerged (sex: pValueisom=0.63; pValueisot=0.22; age: pValueisom=0.78; pValueisot=0.058). The intestinal tract of the sample source (either ileum or colon) did not seem to influence contractile behavior when the overall dataset was evaluated (pValueisom=0.11; pValueisot=0.067) (Fig. 3A,B). Not enough data from a single patient were available to clearly elucidate if a substantial difference exists between the colon and the ileum derived from the same individual and in the same pathophysiological condition. To provide additional information in this direction, all data of coupled ileum-colon were pooled together, and different colors were associated to identify each subject (Fig. 3C, D) (Figure 2A-F), (Figure 3A-D).

Figure 2: Analysis of the distributions of F and D considering different features of the Ctrl population. Force (F expressed as mN), displacement (calculated as mm and plotted as the percentage of variation in tissue length, L: D%=D*100/L) and signal speed (expressed as mm/s) preservation mode: (A) Isometric data. Nfresh=6, Rfresh=23, Nfrozen=6, Rfrozen=15. (B) Isotonic data. Nfresh=6, Rfresh=13, Nfrozen=6, Rfrozen=28. Sex: (C) Isometric data. NFemale=5, RFemale=18, NMale=6, RMale=19. (D) Isotonic data. NFemale=5, RFemale=20, NMale=7, RMale=22. Age: (E) Isometric data. NAge<8=7, RAge<8=21, NAge>8=6, RAge>8=16. (F) Isotonic data. NAge<8=7, RAge<8=12, NAge>8=6, RAge>8=32.

Figure 3: Analysis of the distributions of F and D considering different features of the Ctrl population. Sample origin from the intestinal segment: (A) Isometric data. N_ileum=10, R_ileum=29, N_colon=4, R_colon=8. (B) Isotonic data. N_ileum=9, R_ileum=28, N_colon=5, R_colon=12. Ileum & Colon subjects force (C) Isometric data. N_ileum=4, R_ileum=7, N_colon=4, R_colon=9, different colors indicate different subjects (purple dots: subject 6, green dots: subject 7, orange dots: subject 16, blue dots: subject 8). Ileum & Colon subjects displacement: (D) Isotonic data. N_ileum=4, R_ileum=5, N_colon=4, R_colon=5, different colors indicate different subjects as before.

Force exerted during contraction of affected tissues

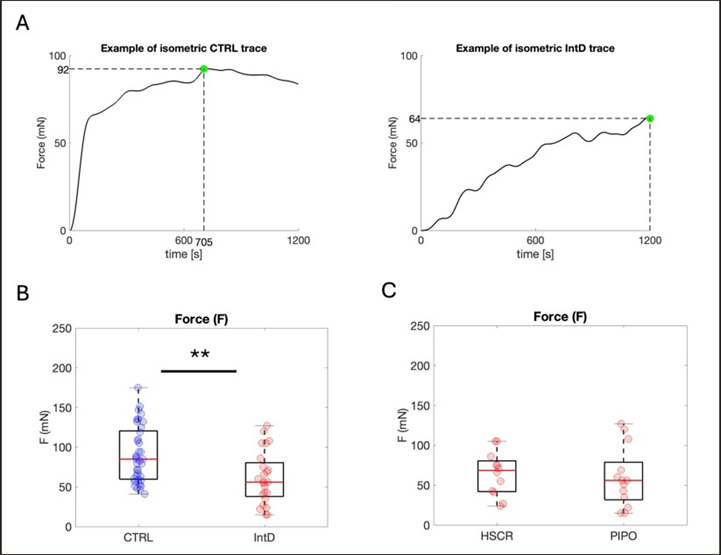

The principal finding of the study concerns the evaluation of the force associated with the contractile activity of gut tissues from patients affected with intestinal dysmotility (IntD) and control subjects (Ctrl). Examples of conditioned isometric signals from the IntD and Ctrl populations are shown in Fig. 4A. The maximum force value (Fmax) of the sample set reached during contraction monitoring over 1200 sec, in the affected sample (colon sample from the myogenic-PIPO affected child) was much lower than the Fmax reached by the control (colon sample from control subject #8, Table 1). When comparing PIPO-affected patients with HSCRaffected patients, no significant difference in force was observed (Table 2). This test allowed pooling results from the PIPO (yellow dots) and HSCR samples together in the IntD set (Fig. 4C). Statistical analysis of force data from the Ctrl population compared with the total IntD population revealed that the former was significantly greater than the other (pValue = 0.011) (Fig. 4C, Table 2) (Figure 4A-4C).

Figure 4: Force exerted during tissue contraction. (A) Examples of typical smoothed traces of force signals in cases and controls. Time=0: CCh administration. Green dot=Fmax. (B) Isometric data distribution of Ctrl (blue) and IntD (red) population data. Yellow dots: PIPO population values. Nctrl=11, Rctrl=37, NIntD=4, RIntD=24. (C) Isometric data distribution of the HSCR and PIPO population data. Yellow dots: PIPO population values. NHSCR=3, RHSCR=12, NPIPO=2, and RPIPO=13.*: 0.01

F (mN) | |||

Ctrl | IntD | pValue | |

84; 62.50 | 58; 40 | 0.011* | |

HSCR | PIPO | pValue | |

75; 30.25 | 56; 47 | 0.20 |

Table 2: Results from force measurements, Contractile force exerted by tissues (median; iQR) after CCh administration. *statistically significant difference, 0.01

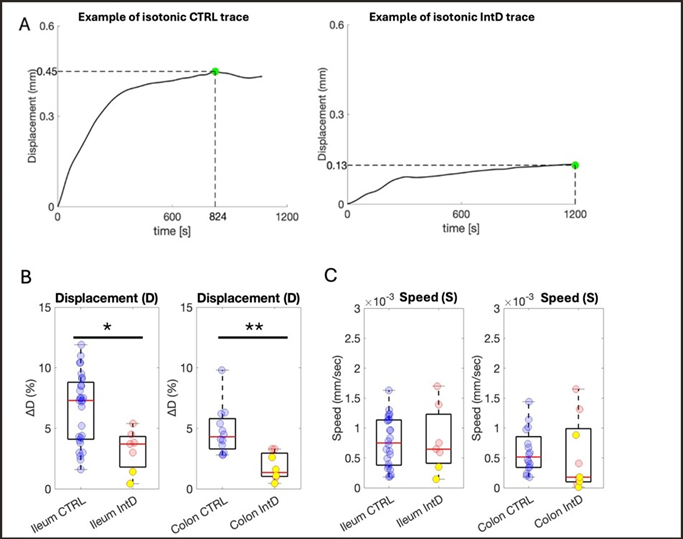

Displacement occurring during contraction of affected and healthy tissues

When contraction-associated displacement was measured, signals appeared substantially different between the IntD and Ctrl populations. Examples of traces of conditioned isometric signals obtained from the contraction of affected and not-affected colons are reported in Fig. 5A. The maximum value of displacement in the IntD population (in this case, a colon sample from myogenic PIPO-affected child) is substantially lower than that observed from the control tissue set (in this case, a colon sample from control subject #12, Table 1). Table 3 reports the percental median displacement values in patient and control populations. Statistical analysis confirmed significant differences (pValue = 1.80e-05) (Fig. 5B). For this parameter, only one PIPO case was available for test (2 colon samples and 4 ileum samples, yellow dots in Fig. 5B), limiting the possibility of comparing HSCR to PIPO distribution (Table 3).

|

D% |

||

|

Ctrl |

IntD |

pValue |

|

4.45; 3.7 |

1.25; 1.64 |

1.80e-05** |

|

HSCR |

PIPO |

pValue |

|

3.15; 7 |

1.25; 1.15 |

0.11 |

Table 3: Results from displacement measurements; Displacement occurred in tissues (median; iQR) after CCh administration.

**statistically significant difference, p value<0.01.

Displacement speed during contraction

To gain further insight into gut tissue contraction in the presence of intestinal dysmotility, the speed (S), considered as the time necessary for the tissue to reach the maximum value of displacement, was calculated. A statistically significant difference emerged comparing IntD to controls (pValue = 0.0018) (Fig. 5C, Table 4). As in the case of displacement analysis, only one PIPO patient was involved in this evaluation (due to the small amount of available tissue, yellow dots in Fig. 5C) limiting the possibility to obtain robust statistics for single PIPO and HSCR subgroups (Figure 5A-5C), (Table 4).

|

S (mm/sec) |

||

|

Ctrl |

IntD |

pValue |

|

6.13-04; 6.82e-04 |

2.21e-04; 2.76e-04 |

0.0018 ** |

|

HSCR |

PIPO |

pValue |

|

1.64e-04; 7.0e-04 |

1.44e-04; 2.09e-04 |

0.55 |

Table 4: Results from speed measurements; Speed enabled by tissues (median; iQR) after CCh administration. **statistically significant difference, p value<0.01.

Figure 5: Percental tissue displacement and speed exerted during contraction. (A) Examples of typical smoothed traces of isotonic signals from Ctrl and IntD samples. Time=0: CCh administration. Green dot=Dmax. (B) Distribution of percent displacement values comparing the Ctrl (blue) and IntD (red) populations. Yellow dots: PIPO population values. Nctrl=11, Rctrl=41, NIntD =3 RIntD=18. (C) Distribution of speed values comparing the Ctrl (blue) and IntD (red) populations. Yellow dots: PIPO population values. Nctrl=11, Rctrl=40, NIntD=3, RIntD=16**: p value<0.01.

Discussion

Ex vivo tissues retain multiple levels of information that can recapitulate the pathological processes related to the disease they harbor. Compared to cell cultures, which represent simplified models, tissue-based analyses offer insights into both structural and functional aspects within a more complex biological context.

The availability of intestinal tissues from patients with gut dysmotility is rare, especially for the most severe forms of dysmotility (PIPO). This is ascribable to the rarity of such disorders and to recent recommendations on limiting surgical intervention in the presence of PIPO. Similar approaches are available in literature, especially for HSCR disease which, although its rarity, requires surgery as the main currently available therapy thus allowing an easier collection of samples. In this context, Tripathi et al [20] analysed the response of colonic strips of HSCR in organ bath, assessing that they did not show any spontaneous contractions but responded to CCh and ET-1. Vizi et al [21] studied the neurochemical stimulation in aganglionic and ganglionic segments of human colon isolated from children suffering from HSCR, showing that pattern of response to organ bath transmural stimulation was different in the spastic (aganglionic, only contractions) and dilated (ganglionic, relaxation – contraction or vice versa) bowel, and that the release of acetylcholine was significantly higher in the spastic segment.

Similarly, Kamimura et al. [22] evaluated the pattern of response in short-segment and long-segment types of HSCR, showing that in the aganglionic preparations from the short-segment-type cases, stimulation evoked only an atropine-sensitive contraction, while in the aganglionic preparations from the long-segment-type cases, a weak inhibitory response persisted after the contractile response was abolished by atropine. More recently, Jevans et al [23] used the organ bath (with electrical field stimulation) to obtained contractility data from human ENS-transplanted samples gut tissues of pediatric HSCR cases.

Working on PIPO is much rarer and difficult, and the only available literature regards Do et al. [24] who analyzed colon tissues from adult patients with intractable constipation with severe dilation of the proximal colon probably ascribable to CIPO (not genetically ascertained). They showed that, when assessed through CCh stimulation in organ bath, the amplitude of spontaneous phasic activity of circular colon muscle was significantly decreased respect to cancer controls. Moreover, CIPO tissues were approximately 10 times less sensitive to stimulation of by CCh than colon cancer. They did not study the behavior of the longitudinal muscle nor the contraction performance in terms of displacement and speed. At best of authors’ knowledge, no other study has been published to quantify the contraction of gut tissues from PIPO patients: such tissues are extremely rare. The collaboration with a pediatric hospital (IRCCS Istituto Giannina Gaslini in Genoa, Italy) allowed to collect samples from both patients affected with primary genetic PIPO, HSCR, where the intestinal dysmotility is tightly correlated with defects of ENS or SIP syncytium, and controls.

Measurement of the mechanical features of intestinal tissues is challenging because structural and functional aspects are typical of the gut [25]. From this perspective, the setup of well-defined working and experimental conditions in contraction assessment is crucial to avoid misleading interpretations of results. In fact, the evaluation of gut tissue contraction is not only the assessment of a passive material feature, such as elasticity. Rather, it consists of the evaluation of the functional ability of an active living material, as in the case of distensibility/tone [13]: it depends not only on the passive properties of the tissue but also on the physiological/ pathological state of the structural and functional components of the gut. To assess muscle contractility, no external force was applied to intestinal segments: sample were kept in their relaxed configuration and stimulation was performed chemically, to induce the molecular cascade responsible for gut muscle contraction. To measure the triggered contraction, a simple, robust, low-cost, home-assembled device was developed, able to characterize sample activity in terms of exerted force (F, through an isometric sensor), relative displacement and displacement speed (D% and S respectively, through an isotonic sensor).

A preliminary analysis was needed to assess the homogeneity of the control cohort, which was composed of subjects affected with pathologies other than genetic primary PIPO or HSCR (Table 1). Among considered controls, patients affected with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) and necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) were included. These diseases can, in a few cases, present intestinal pseudo-obstruction as secondary manifestations [26,27]. In order to recruit control subjects correctly, the clinical history of each patient was screened, to avoid the inclusion of possible pseudoobstructive conditions in the Ctrl population. Patient sex and age, as well the sample preservation mode did not seem to impact the contractile features of samples (Fig. 2).

For assessing the impact of the gut tract on contraction, two analyses were carried out: one including all data from Ctrl colon compared to all data from Ctrl ileum (Fig. 3A,B), and another including data from ‘coupled’ ileum-colon derived from the same individuals (Fig. 3C,D). The latter seems to support the idea that the colon and the ileum from the same individual can contract differently in terms of force and displacement, although it is not possible to identify a clear and homogeneous trend across subjects. Differences could be ascribed to the different stiffness values known to be associated with these two bowel segments [18,19], as well as to the potentially different impact of a disease on diverse gut tracts. Interestingly, when data from all colons are pooled together and compared to all ileums, as whole datasets, no statistically significant difference emerges between these groups, leading the hypothesis that, when studying intestinal contraction of a cohort of patients, data from ileums and colons can be reasonably pooled together. Observations on the Ctrl population suggest maintaining ileum and colon data together when comparing the group of affected samples (IntD) with the control set.

The IntD cohort includes 3 HSCR cases and 2 PIPO-affected subjects. Sample staining (Figures S1-S15) revealed that the mitochondrial PIPO case presented a dysfunctional intestine (villous atrophy and intraepithelial lymphocytosis), and the myogenic PIPO subject exhibited marked thinning of the muscle wall, whereas tissues from HSCR-affected patients were sampled from the aganglionic regions of their gut.

The results of the present pilot study highlight alterations in the contractile behavior of intestinal smooth muscle tissues from individuals affected with primary PIPO and HSCR, compared to controls. Despite the intrinsic genetic and etiological differences between the two diseases, in primary PIPO and HSCR conditions the similar clinical phenotypes of intestinal dysmotility, often ascribable to genetic defects of ENS or SIP syncytium, reflect in the functional impairment at tissue level. Such information is accessible through ADM in indirect form, by measuring the neuromuscular motility of gastric antrum and proximal small bowel [28]. Here, we assessed the contraction force, displacement and speed of gut muscle quantitatively and directly on tissues, by comparing performance of dysmotility cases to control samples harbouring different pathologies. These insights increase the information associated with these rare and only partially elucidated pathologies, contributing to reduce the gap between the clinical knowledge [2,3,4] and the mechanical knowledge at cellular level [17,29]. When samples from affected subjects and control patients were compared, the force in the IntD group was quite homogeneous within the dataset (Fig. 4, PIPO samples in yellow dots) and significantly lower than that in the control group (Fig. 4, Table 2), as expected. Unfortunately, due to the low amount of available tissue, data collected by means of the isotonic sensor was obtained only from one PIPO patient (affected by the myogenic form of PIPO), making it impossible to provide statistics on PIPO displacement and speed. Similar results were obtained for the displacement parameter, where the Ctrl population presented significantly greater displacement with respect to the IntD population (Fig. 5). Results are in agreement with findings by Tiwari et al. [13]. Such contraction defects also clearly appear from the recorded signals: typical trends (Figs. 4,5) revealed that, in the 20-minute span of data acquisition, the isotonic and isometric sensors registered sensibly lower signals for the IntD population with respect to the Ctrl population. Finally, also in terms of speed (Fig. 5C), the Ctrl and IntD populations were significantly different.

The paper provides quantitative measurement of the contraction capability of primary genetic PIPO and HSCR compared to controls. Moreover, the proposed approach is promising prospectively, since it may be fruitfully applied to the fields of therapy identification. In fact, tissue contraction assay could serve as a functional platform to support the testing of new pharmacological strategies. When a possibly effective treatment is envisaged, the availability of samples and functional tools is pivotal to proceed in preclinical investigations. Contraction has been identified (also at cellular level - 17, 29 ) as a feature tightly correlated with the disease, therefore each non-toxic molecule that ameliorates the model contraction is expected to improve the condition of the gut in patients. In this perspective, although testing specific therapeutic molecules is out of the scope of the present work, the availability of a tool for functional assessment in 3D samples can be valuable to support this kind of screening. An example is provided by Tiwari et al. [13] who demonstrated that histamine can promote smooth muscle contraction in the presence of HSCR.

Future improvements and considerations could further increase the significance of the study. The first aspect regards sample availability. Limited sample size is ascribable to the rarity of genetically ascertained primary PIPO and HSCR, and the fact that, concerning PIPO, guidelines recommend avoiding surgical procedures when not strictly necessary [2]. Increasing the number of involved patients, through national or international multi-center collaborations, would strengthen the significance of statistical analysis, also enabling possible comparative evaluations between primary genetic PIPO and HSCR populations, which would support the identification of shared and distinct features among these two pathological conditions. Also, the availability of a wider PIPO patients cohort would allow to test the value of the approach in differential diagnosis across PIPO origins.

Another pivotal aspect for the correct implementation of the described approach is related to the choice of the Ctrl population. Patient inclusion criteria should always consider the clinical history of recruited subjects, to exclude from controls those patients referring episodes of pseudo-obstruction, which could interfere with the contractile performance of their gut tissues. For example, secondary pseudo-obstructive events could be associated, in rare cases, with NEC [27] or Crohn’s disease [26], caused by inflammation or malabsorption. Ad hoc future studies could be envisaged to assess the possible direct impact of such pathological conditions on tissue contraction performance.

Moreover, the selection of tissue samples from HSCR-affected patients should be well defined. In the present study, only aganglionic samples were considered, following the idea that they recapitulate the disease. The same selection is suggested when reproducing the proposed approach, although a comparative functional evaluation between healthy (ganglionic) and affected (aganglionic) tissues from the same intestinal tract of the same individual would allow to further advance, other than what already tested [30], in the knowledge of the disease.

Finally, a couple of considerations related to intrinsic gut complexity are useful. First, the present study is focused on contraction of gut longitudinal muscle, neglecting the circular muscle activity, which also plays a crucial role in gut movements. The assessment of both contraction directions would need either the use of biaxial expensive tools, or the availability of much larger tissue sections from each patient to hang up the specimen partially in longitudinal and partially in circular directions. The other comment regards the difficulty of reproducing the in vivo environment, where the contraction activity relies on a multifactorial trigger that involves SIP syncytial activity coupled to complex biomolecular interactions, such as those ascribable to microbiota interactions [31]. Both these final issues would imply the use of much more complex and expensive setups and would be encouraged for future developments of the research field.

Conclusions

This work represents a pilot investigation of the contractile activity of intestinal tissues in the gut affected by primary PIPO of ascertained genetic origin and HSCR compared to controls. This study highlights the potential of tissue functional contractility assays to as sources of information for increasing the knowledge of these rare diseases. In perspective, such approach could be exploited as tool for the identification of promising therapeutic molecules.

Further studies are needed to strengthen the investigation and corroborate the proposed results. In particular, future research should aim to increase the sample set to reinforce the robustness of statistical comparisons between subgroups (HSCR and PIPO), explore additional motility parameters (such as evaluations of the circular muscle layer), and integrate complementary approaches, such as 3D in vitro/organoid models or electrophysiological studies, to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the cause of deficient tissue contraction. Considering the rarity of the disease and the scarce availability of samples, national or international cooperation is recommended.

Author Contributions

MP, CP: performed experiments. CP, FV: conceived and designed research, interpreted results of experiments. MP: analyzed data, interpreted results of experiments, drafted manuscript. MP, AB: developed the setup. CP, RB, Gaslini staff: provided and prepared samples. JF prepared supplementary materials. All authors: edited and revised manuscript, approved final version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was funded by Telethon Seed Grant (# GSA22Q001), PRIN 2022 - Grant n. 2022JKEBB8. PNRR-MR1-2023-12378468 (M6.C2.I2.1) funded by European Union - NextGeneration EU

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The following figures are available in the Supplementary Materials File: (Figures S1--S4).

References

- Cooper GM (2000) Actin, Myosin, and Cell Movement. In: The Cell: A Molecular Approach 2nd edition (Internet). Sinauer Associates.

- Thapar N, Saliakellis E, Benninga MA, Borrelli O, Curry J, et al. (2018) Paediatric Intestinal Pseudo-obstruction: Evidence and Consensusbased Recommendations From an ESPGHAN-Led Expert Group. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 66: 991-1019.

- Viti F, Giorgio RD, Ceccherini I, Ahluwalia A, Alves MM, et al. (2023) Multidisciplinary Insights from the First European Forum on Visceral Myopathy 2022 Meeting. Digestive Diseases and Sciences 68: 38573871.

- Martucciello G, Ceccherini I, Lerone M, Jasonni V (2000) Special basic science review: Pathogenesis of Hirschsprung’s disease. J Pediatr Surg 35: 1017-1025.

- Xie C, Yan J, Guo J, Liu Y, Chen Y (2023) Comparison of clinical features and prognosis between ultrashort-segment and shortsegment hirschsprung disease. Frontiers in Pediatrics 10:1061064.

- Cheng LS, Wood RJ (2024) Hirschsprung disease: common and uncommon variants. World Journal of Pediatric Surgery 7: e000864.

- Jia Y, Li B, Xi H, Ren H (2025) Hirschsprung’s disease prognosis: significance of the length of aganglionosis and reference value for the dilated segment resection length. Frontiers in Pediatrics 13: 1553317.

- Moore SW (2015) Total colonic aganglionosis and Hirschsprung’s disease: a review. Pediatr Surg Int 31:1-9.

- Caniano DA, Ormsbee HS 3rd, Polito W, Sun CC, Barone FC, et al. (1985) Total intestinal aganglionosis. J Pediatr Surg 20: 456-460.

- Bautista GM, Du Y, Matthews MJ, Flores AM, Kushnir NR, et al. (2025) Smooth muscle cell Piezo1 depletion results in impaired contractile properties in murine small bowel. Commun Biol 8: 448.

- Thoua NM, Derrett-Smith EC, Khan K, Dooley A, Shi-Wen X, et al. (2012) Gut fibrosis with altered colonic contractility in a mouse model of scleroderma. Rheumatology (Oxford 51: 1989-1998.

- Kirschstein T, Protzel C, Porath K, Sellmann T, Köhling R, et al. (2014) Age-dependent contribution of Rho kinase in carbachol-induced contraction of human detrusor smooth muscle in vitro. Acta Pharmacol Sin 35: 74-81.

- Tiwari AK, Singh SK, Pandey R, Singh PB, Patne SCU, et al. (2017) A comparative study of in vitro contractility between gut tissues of Hirschsprung’s disease and other gut malformations. 7: 108.

- Do YS, Myung SJ, Kwak SY, Cho S, Lee E, et al, (2015) Molecular and Cellular Characteristics of the Colonic Pseudo-obstruction in Patients With Intractable Constipation. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 21: 560-570.

- Montgomery LEA, Tansey EA, Johnson CD, Roe SM, Quinn JG (2016) Autonomic modification of intestinal smooth muscle contractility. Adv Physiol Educ 40: 104-109.

- Patcharatrakul T, Gonlachanvit S (2013) Technique of functional and motility test: how to perform antroduodenal manometry. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 19: 395-404.

- Viti F, Pramotton FM, Martufi M, Magrassi R, Pedemonte N, et al.(2023) Patient’s dermal fibrolasts as disease markers for visceral myopathy. Biomater Adv 148: 213355.

- Massalou D, Masson C, Afquir S, Baqué P, Arnoux PJ, et al. (2019) Mechanical effects of load speed on the human colon. J Biomech 91: 102-108.

- Creff J, Malaquin L, Besson A (2021) In vitro models of intestinal epithelium: Toward bioengineered systems. J Tissue Eng 12: 2041731420985202.

- Tripathi BK, Gangopadhyay AN, Sharma SP, Kar AG, Mandal MB (2016) In Vitro Evaluation of Carbachol and Endothelin on Contractility of Colonic Smooth Muscle in Hirschsprung’s Disease. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol 60: 22-29.

- Vizi ES, Zséli J, Kontor E, Feher E, Verebélyi T (1990) Characteristics of cholinergic neuroeffector transmission of ganglionic and aganglionic colon in Hirschsprungs disease. Gut 31: 1046-1050.

- Kamimura T, Kubota M, Suita S (1997) Functional innervation of the aganglionic segment in Hirschsprung’s disease--a comparison of the short- and long-segment type. J Pediatr Surg 32: 673-677.

- Jevans B, Cooper F, Fatieieva Y, Gogolou A, Kang YN, et al. (2024) Human enteric nervous system progenitor transplantation improves functional responses in Hirschsprung disease patient-derived tissue. Gut 73: 1441-1453.

- Do YS, Myung SJ, Kwak SY, Cho S, Lee E, et al. (2015) Molecular and Cellular Characteristics of the Colonic Pseudo-obstruction in Patients With Intractable Constipation. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 21: 560-570.

- Gregersen H, Kassab G (1996) Biomechanics of the gastrointestinal tract. Neurogastroenterol Motil 8: 277-297.

- Barros LL, Farias AQ, Rezaie A (2019) Gastrointestinal motility and absorptive disorders in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: Prevalence, diagnosis and treatment. World J Gastroenterol 25: 4414- 4426.

- Kovler ML, Gonzalez Salazar AJ, Fulton WB, Lu P, Yamaguchi Y, et al. (2021) Toll-like receptor 4-mediated enteric glia loss is critical for the development of necrotizing enterocolitis. Sci Transl Med 13: eabg3459.

- Rybak A, Saliakellis E, Thapar N, Borrelli O (2022) Pediatric Neurogastroenterology: Gastrointestinal Motility Disorders and Disorders of Gut Brain Interaction in Children [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 131-144.

- Hashmi SK, Barka V, Yang C, Schneider S, Svitkina TM, et al. (2020) Pseudo-obstruction–inducing ACTG2R257C alters actin organization and function. JCI Insight 5 : e140604.

- Vizi ES, Zséli J, Kontor E, Feher E, Verebélyi T (1990) Characteristics of cholinergic neuro effector transmission of ganglionic and aganglionic colon in Hirschsprungs disease. Gut 9: 1046-1050.

- Bai X, Ihara E, Tanaka Y, Minoda Y, Wada M, et al. (2025) The interplay of gut microbiota and intestinal motility in gastrointestinal function. J Smooth Muscle Res 61: 51-58.

Supplementary Files

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.