Clinical Analysis of Secondary Carnitine Deficiency in Pediatric Patients at a Single Institution

by Atsuya Inoue1, Hisashi Kawashima1,2*, Natsumi Morishita1,2, Shinichiro Morichi1, Shigeo Nishimata1, Gaku Yamanaka1

1Department of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Tokyo Medical University, Tokyo, Japan

2Department of Pediatrics, Kohseichuo General Hospital, Tokyo, Japan

*Corresponding Author: Hisashi Kawashima, Department of Pediatrics, Kohseichuo General Hospital, 1-11-7 Mita, Meguro-ku, Tokyo 153-8581, Japan

Received Date: 02 February 2026; Accepted Date: 10 February 2026; Published Date: 12 February 2026.

Received Date: 02 February 2026

Accepted Date: 10 February 2026

Published Date: 12 February 2026

Citation: Inoue A, Kawashima H, Morishita N, Morichi S, Nishimata S, et al. (2026) Clinical Analysis of Secondary Carnitine Deficiency in Pediatric Patients at a Single Institution. Arch Pediatr 11: 337. https://doi.org/10.29011/2575-825X.100337

Abstract

Background: Carnitine is a conditionally essential amino acid that is primarily obtained through dietary intake, and is synthesized endogenously in the liver, kidneys, and brain. It plays a crucial role in fatty acid metabolism, particularly in skeletal and cardiac muscles. Objective: In this study, we retrospectively evaluated the clinical features and therapeutic responses of pediatric patients diagnosed as having secondary carnitine deficiency at our institution. Methods: Medical records of 213 pediatric patients who underwent carnitine level testing between January 2017 and December 2021 were reviewed. Of these, 77 patients were identified as having either carnitine deficiency (free carnitine < 20 μmol/L) or being at high risk of developing carnitine deficiency (free carnitine 20–36 μmol/L, with an acylcarnitine-to-free carnitine [AC/FC] ratio > 0.4). Pre-supplementation and post-supplementation FC levels and AC/FC ratios were analyzed. Statistical significance was assessed using the Mann–Whitney U test. Results: Substantial improvements in both FC levels and AC/FC ratios were observed following carnitine supplementation, particularly among patients with ketotic hypoglycemia and metabolic disorders. In addition, those with a history of pivalate-conjugated antibiotic use demonstrated notably low FC levels and favorable responses to carnitine supplementation. Conclusion: The monitoring of FC levels and AC/FC ratios is essential for pediatric patients at high risk of developing secondary carnitine deficiency. Early carnitine supplementation, tailored to the underlying condition and its severity, is particularly beneficial for patients with ketotic hypoglycemia and those receiving pivalate-conjugated antibiotics.

Keywords: Carnitine deficiency; FC; AC/FC; Pediatrics.

Abbreviations

FC: Free carnitine

AC: Acil carnitine

AC/FC: Acylcarnitine-to-Free carnitine ratio

RSV: Respiratory Syncytial Virus

Introduction

Carnitine plays a central role in energy production, by transporting long-chain fatty acids into mitochondria for β-oxidation [1]. Approximately 75% of the body’s carnitine comes from dietary sources, whereas the remainder is synthesized endogenously. The vast majority is stored in skeletal and cardiac muscle [2]. Carnitine deficiency, particularly in pediatric patients, can lead to severe clinical manifestations, such as hypoglycemia, muscle weakness, encephalopathy, and delayed development [1,3]. The 2018 Japanese Clinical Practice Guidelines highlighted the importance of early recognition and treatment of carnitine deficiency, particularly in children with risk factors, such as valproic acid use, long-term enteral nutrition, and antibiotics use [4,5]. Although carnitine plays an important role in fatty acid metabolism, there is still some ambiguity regarding the pathogenesis of carnitine deficiency, particularly secondary carnitine deficiency. Therefore, we conducted a clinical study on carnitine deficiency in pediatric patients at our hospital.

Methods

This was a retrospective observational study. A total of 213 pediatric patients who underwent carnitine profiling at our institution between January 2017 and December 2021 were reviewed. Among them, 77 met the criteria for carnitine deficiency or were at high risk of developing carnitine deficiency. KDK-1201, the carnitine measurement reagent based on the principle of the enzyme cycling method [6], was used to measure serum carnitine levels. Patients with free carnitine (FC) levels of less than 20 μmol/L were defined as having “carnitine deficiency”, and those with FC levels between 20 to 36 μmol/L and acylcarnitine-to-free carnitine (AC/FC) ratios of greater than 0.4 were defined as having a “high risk of deficiency”.

The patients’ diagnoses, nutritional status, medication histories, and laboratory findings were collected. Pre-treatment and post-treatment carnitine levels were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test (cutoff of statistical significance: p < 0.05).

Results

Based on the 2018 Japanese Clinical Practice Guidelines, 77 cases are devided into the following groups: Long-term oral valproic acid treatment (32 cases), Long-term tube feeding, central venous feeding, milk allergy, and fasting (10 cases), Encephalopathy, cerebral hemorrhage, and corpus callosum hypoplasia (10 cases), Metabolic diseases (glycogen storage disease Ⅸa, dicarboxylic aciduria, glutaric acidemia type I, and citrin deficiency and idiopathic ketotic hypoglycemia) (17 cases), Internal use of pivalate-conjugated antibiotics (4 cases), and Others (4cases). Idiopathic ketotic hypoglycemia (10 cases) includes severe hypoglycemia causing convulsive seizures or impaired consciousness, or patients diagnosed by exclusion after a thorough examination of the cause of repeated hypoglycemia.

The incidence of hypocarnitinemia (FC < 20 μmol/L) in the various groups of patients analyzed in the present study was as follows: those with long-term oral valproic acid use, 3 out of 32 patients (9%); those undergoing long-term tube feeding, central venous nutrition, or fasting, 3 out of 10 patients (30%); those with idiopathic ketotic hypoglycemia, 3 out of 10 patients (30%); those with metabolic diseases, including glutaric acidemia type 1, glycogenic disease IXa, citrin deficiency, type 1 citrullinemia, 2 out of 7 patients (29%); and those treated with antibiotics containing a pivoxyl group, 3 out of 4 patients (75%) (Table 1).

|

Condition |

Hypocarnitinemia (FC<20 μmol/L) |

|

Long-term oral valproic acid treatment |

3/32 patients (9%) |

|

Long-term tube feeding, central venous feeding, milk allergy, and fasting |

3/10 patients (30%) |

|

Encephalopathy, cerebral hemorrhage, and corpus callosum hypoplasia |

2/10 patients (20%) |

|

Ketotic hypoglycemia |

3/10 patients (30%) |

|

Metabolic diseases (glycogen storage disease Ⅸa, dicarboxylic aciduria, glutaric acidemia type I, and citrin deficiency) |

2/7 patients (29%) (glycogen storage disease and glutaric acidemia type I) |

|

Internal use of pivalate-conjugated antibiotics |

3/4 patients (75%) |

|

Others (neutropenia, Angelman syndrome, and severe soft tissue infection) |

0/4 patients (0%) |

Table 1: Hypocarnitinemia in children with various conditions.

Of the 77 patients with or at high risk of carnitine deficiency, 40 patients received carnitine supplementation (Table 2), and among those, 31 patients subsequently underwent carnitine analysis.

|

Group |

Number of cases (%) |

Treatment period (Range) |

Median supplement amount (mg/kg/day) (IQR) |

|

Long-term oral valproate treatment |

18/32 (56%) |

5 days – 5 years |

31.5 (20–50) |

|

Long-term enteral nutrition, central venous nutrition, milk allergy, fasting, and other types of malnutrition |

4/10 (50%) |

3 weeks – 1.5 years |

14.3 (7.2–53) |

|

Encephalopathy, hypoplasia, and cerebral hemorrhage |

6/10 (60%) |

5 days – 10 years |

34 (23.8–41) |

|

Ketotic hypoglycemia |

4/10 (40%) |

5 days – 1 year |

26 (24.3–36.8) |

|

Metabolic disorders |

2/4 (50%) |

5 years, 10 years |

3.3, 10 |

|

Oral pivalate-conjugated antibiotics treatment |

4/4 (100%) |

1 month – 1 year |

37.5 (30–48.8) |

|

Others (neutropenia, Angelman syndrome, and severe soft tissue infection) |

2/4 (60%) |

1 month – 1 year |

100 (55–118) |

Table 2: Summary of the treatment groups in this study; IQR; Interquartile Range.

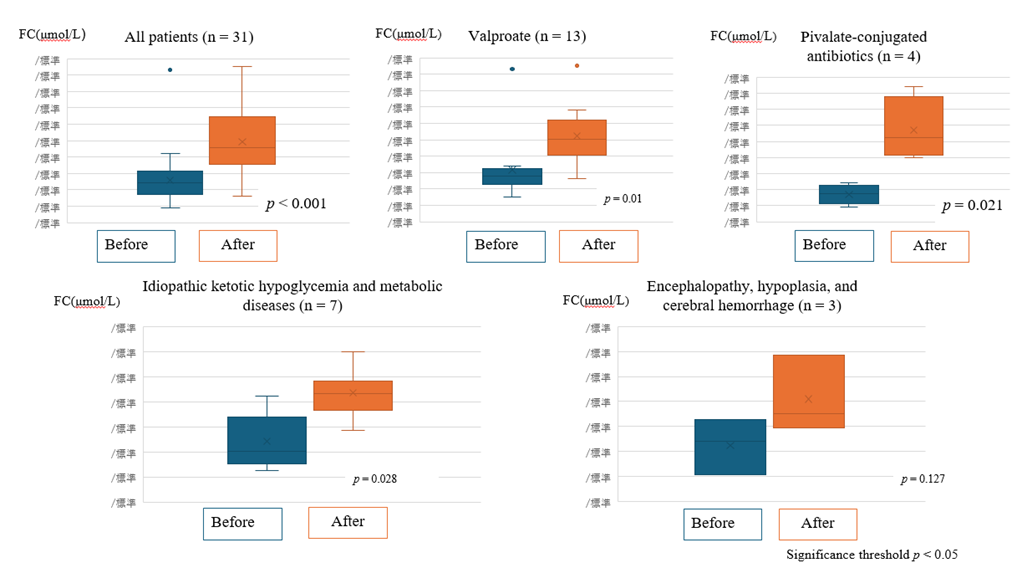

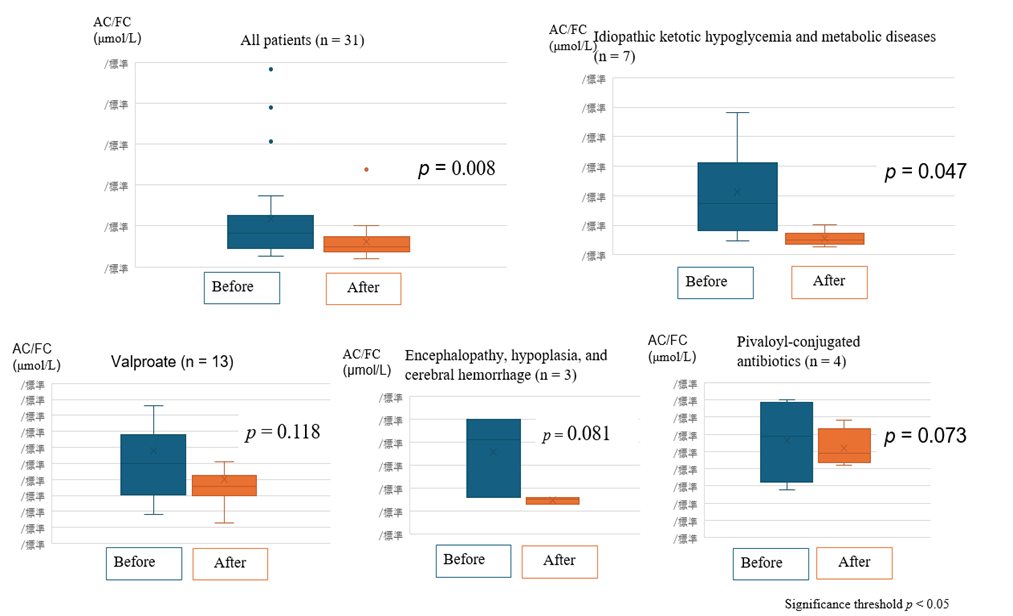

Carnitine administration improved both FC levels (Figure 1) and AC/FC ratios (Figure 2) in all 31 patients. The group of patients with poor oral intake was excluded, because all of these patients had underlying diseases, making an accurate evaluation difficult. The remaining 27 patients were classified by group, and FC levels and AC/FC ratios before and after supplementation were summarized for each group. The patients with idiopathic ketotic hypoglycemia had the highest median AC/FC ratio of 1.39 (IQR, interquartile range: 0.57–1.58), and these patients were classified in the same group as patients with metabolic disorders.

Figure 1: Free carnitine (FC) levels of the patients before and after carnitine supplementation.

Comparison of free carnitine levels before and after carnitine supplementation in each treatment group. Statistically significant increases were observed except for the group of Encephalopathy, hypoplasia, and cerebral hemorrhage.

(All p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant).

Figure 2: AC/FC ratios of the patients before and after carnitine supplementation.

Acylcarnitine-to-free carnitine ratios before and after carnitine supplementation. Significant reductions were observed in the group of Idiopathic ketotic hypoglycemia and metabolic diseases.

(All p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant).

Significant increases in FC levels and improvements in AC/FC ratios were observed post-supplementation in patients with idiopathic ketotic hypoglycemia (p < 0.001) and metabolic disorders, such as glutaric acidemia and citrullinemia. Patients treated with pivalate-conjugated antibiotics for recurrent otitis media (duration > 7 days) showed marked carnitine depletion and increased risk of hypoglycemia and consciousness disturbances. These patients responded well to carnitine supplementation (p = 0.01 for FC).

Discussion

Secondary carnitine deficiency remains an underdiagnosed yet clinically important metabolic disturbance in pediatric patients, particularly in those with chronic illnesses, nutritional compromise, or taking specific medications. Our retrospective analysis adds to the growing body of literature highlighting the clinical importance of identifying and treating carnitine deficiency in children at risk, particularly those with ketotic hypoglycemia, metabolic disorders, and pivalate-conjugated antibiotics use [7-9].

The pathophysiology of secondary carnitine deficiency is multifactorial. Regarding pivalate exposure, the ester binds to carnitine and is excreted via urine, resulting in molar-equivalent carnitine loss. Our findings support previous reports that even short-term pivalate-conjugated antibiotics administration can cause substantial carnitine deficiency.

Patients on elemental diets or parenteral nutrition demonstrated markedly reduced FC levels, likely owing to insufficient dietary intake of carnitine. This is consistent with prior studies indicating that insufficient carnitine availability compromises mitochondrial β-oxidation and energy production, potentially leading to metabolic decompensation [10, 11].

Inadequate dietary intake can also cause ketotic hypoglycemia. Although carnitine deficiency causes hypoketotic hypoglycemia owing to impaired β-oxidation, there has been one case report of ketotic hypoglycemia caused by the oral administration of antibiotics containing a pivoxyl group [12]. In our cohort, patients with ketotic hypoglycemia had the highest AC/FC ratios, and their FC levels and AC/FC ratios improved with the use of carnitine. The roles of carnitine include buffering of the acyl coenzyme A (CoA)-CoA ratio, branched-chain amino acid metabolism, removal of excess acyl groups, and peroxisomal fatty acid oxidation. Disorders of fatty acid oxidation and metabolism associated with carnitine deficiency include increased lipid breakdown, increased lipid peroxidation, accumulation of acylcarnitine, and abnormal membrane permeability [13]. We considered the possibility that severe ketotic hypoglycemia may involve an increase in acylcarnitine associated with increased fatty acid metabolism.

Based on these considerations, AC/FC ratios and FC levels may indicate the following:

A high AC/FC ratio indicates an increased demand for carnitine, as observed in patients with metabolic conditions and during energy stress. A low FC level indicates a decreased supply of carnitine, as seen in patients with low oral carnitine intake or medication-associated carnitine loss.

Importantly, our findings are supported by prior observations in patients with CHARGE syndrome who developed metabolic encephalopathy during respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection [14]. In one such patient, profound carnitine deficiency accompanied by rhabdomyolysis and hepatic dysfunction was observed. Mitochondrial pathology, as evidenced by lipid droplet accumulation and loss of mitochondrial cristae, suggested that carnitine depletion substantially exacerbated RSV-associated metabolic stress. In contrast, another CHARGE syndrome patient receiving ongoing L-carnitine supplementation recovered uneventfully from RSV infection despite similar hepatic involvement. These cases underscore the protective role of L-carnitine, likely through the stabilization of mitochondrial function and mitigation of the effects of reactive oxygen species [14,15].

The therapeutic benefits of carnitine supplementation are further substantiated by studies demonstrating improvements in mitochondrial respiration, hepatic enzyme normalization, and neurological outcomes in patients with various metabolic conditions [10,14]. In our study, FC levels and AC/FC ratios significantly improved after carnitine supplementation. The prompt clinical response observed in patients receiving pivalate-conjugated antibiotics highlights the need for heightened awareness among physicians prescribing such medications, particularly when treating infants and children with limited carnitine reserves [7].

In conclusion, the early recognition and treatment of secondary carnitine deficiency is essential in pediatric patients at risk of metabolic decompensation. Our findings, together with corroborative evidence from encephalopathy cases, highlight the potential benefits of proactive carnitine monitoring and targeted supplementation. These interventions may be particularly important in preserving organ function and improving patient outcomes during periods of metabolic stress, such as acute infections and surgical disease [8,9,16].

Conclusions

In pediatric patients with risk factors of secondary carnitine deficiency, proactive monitoring of their FC levels and AC/FC ratios is essential. Dose adjustment of carnitine based on the clinical severity and background of their disease is crucial. In the future, the contribution of carnitine deficiency to clinical symptoms should be further clarified through the accumulation of additional cases and prospective analyses.

Author contributions

HK designed the study; AI, NM, SM, and SN performed the experiments, and collected and analyzed the data; HK wrote the manuscript; and SN and GY provided technical support and conceptual advice. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED); (grant no. 20fk0108119h0001 to HK).

Institutional review board statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Tokyo Medical University (study approval no.: SH3841).

Informed consent statement

Serum samples were obtained with informed consent from the parents of all patients at the time of their hospital admission.

References

- Longo N, di San Filippo CA, Pasquali M (2006) Disorders of carnitine transport and the carnitine cycle. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 142C: 77-85.

- El-Hattab AW, Scaglia F (2015) Carnitine transport and fatty acid oxidation. Biochim Biophys Acta 1852: 1509-1512.

- Wang Y, Korman SH, Ye J (2019) Primary carnitine deficiency: clinical, biochemical, and molecular spectrum in a Chinese pediatric cohort. Orphanet J Rare Dis 14: 53.

- Medscape (2023) Carnitine Deficiency: Clinical Presentation.

- The Japanese Society for Pediatric Nutrition and Metabolism (2018). Clinical Practice Guideline for Carnitine Deficiency (2018). Tokyo: JSPNM; 2018. (in Japanese).

- Takahashi M, Ueda S, Misaki H, Sugiyama N, Matsumoto K, et al. (1994) Carnitine determination by an enzymatic cycling method with carnitine dehydrogenase. Clin Chem 40: 817-821.

- Kobayashi H, Sugiyama T, Takahashi T, Matsumoto S, Yamada K( 2016) Clinical Features of Carnitine Deficiency Secondary to Pivalate-Conjugated Antibiotic Therapy. J Pediatr 170: 204-208.

- Okumura A, Hayashi M, Shimizu T, Kidokoro H, Osawa M (2011) Acute Encephalopathy in a Child with Secondary Carnitine Deficiency Due to Pivalate-Conjugated Antibiotics. Pediatr Infect Dis J 30: 92-94.

- Yamamoto S, Wada Y, Yoshino M, Kobayashi H, Hasegawa Y (2020) Secondary Carnitine Deficiency in Children With Metabolic Disorders. Mol Genet Metab Rep 24: 100607.

- Tanizaki R, Oishi M, Hino T, Iwata M, Nakamura M, et al. (2015) Clinical and Biochemical Characteristics of Secondary Carnitine Deficiency in Pediatric Patients on Parenteral Nutrition. JPEN 39: 701-706.

- Korman SH, Gutman A, Brooks R, Barash V, Orr-Urtreger A, et al. (2026) Carnitine and its Role in Pediatric Metabolic Disease. Eur J Pediatr 165: 479-485.

- Hayashi T (2016) A Patient with Secondary Carnitine Deficiency Presenting with Ketotic Instead of Non-ketotic Hypoglycemia. J Jpn Pediatr Soc 120: 1797-1801.

- Hoppel C (2003) The role of carnitine in normal and altered fatty acid metabolism. Am J Kidney Dis 41: S4-12.

- Kawashima H, Inoue A, Morichi S, Nishimata S, Tsutsumi N, et al. (2025) Respiratory syncytial virus infection in patients with CHARGE syndrome. J Clin Med Case Reports, Images 2: e1–e5.

- Ishikawa H, Takahashi Y, Yamamoto Y, Uchida Y, Kawano K, et al. (2014) L-Carnitine Prevents Progression of Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis in a Mouse Model With Upregulation of Mitochondrial Pathway. PLoS ONE 9: e100627.

- Oh H, Kim YJ, Lee HJ, Park JH, Kim JH (2022) L-Carnitine Supplementation and Liver Enzyme Normalization in Chronic Liver Disease: Meta-Analysis. J Pers Med 12: 1053.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.