Characterization of Muscle Activation Performance for Manual and Automated Workflows During Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial

by Elisabetta Ferrari1, David Fawley2*, Lucie Gale1, John Redmond3, Henry Clayton Thomason4, Charlie Yang5, J.Craig Morrison6, Brian P. Gladnick7

1 DePuy Synthes, St. Anthony’s Road, Leeds, United Kingdom

2 DePuy Synthes, 700 Orthopaedic Drive, Warsaw, IN, USA

3 Redmond Orthopedic Institute, 103 Memorial Medical Parkway, Daytona Beach, FL, USA

4 Carolina Orthopaedic & Sports Medicine Center, 2345 Court Drive, Gastonia, NC, USA

5Colorado Joint Replacement, Centura, 2535 S. Downing Street, Suite 100, Denver, CO, USA

6Southern Joint Replacement Institute, 2400 Patterson Street, Suite 100, Nashville, TN, USA

7W.B. Carrell Memorial Clinic, 9301 North Central Expressway, Tower I, Suite 500, Dallas, TX, USA

*Corresponding author: David Fawley, DePuy Synthes,700 Orthopaedic Drive, Warsaw, IN, USA

Received Date: 26 November 2025

Accepted Date: 04 December 2025

Published Date: 06 December 2025

Citation: Ferrari E, Fawley D, Gale L, Redmond J, Thomason HC, et al. (2025) Characterization of Muscle Activation Performance for Manual and Automated Workflows During Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial. J Surg 10:11501 https://doi.org/10.29011/2575-9760.011501

Abstract

Orthopaedic surgeons perform physically demanding and repetitive tasks during surgery which can lead to injury and absenteeism. During THA, a mallet is traditionally used for multiple impaction steps in the procedure, and an automated surgical impactor has been developed, with a potential to reduce surgeon muscle fatigue and reduce the risk of surgeon injury. The aim of this study was to quantify changes in muscle activation during manual and automated THA workflows to characterize surgeon specific performance, by means of EMG activation changes. As part of a prospective, randomized, controlled trial, four orthopaedic surgeons performed 77 THA cases randomized into two groups: 39 automated impaction cases in the study group, and 38 manual impaction cases in the mallet control group. To record data on muscle performance, surface EMG signals were collected using a compression shirt containing built-in surface electrodes situated over various muscle groups. Surgeons recruited muscle compartments at different intensities. (Surgeon 2) presented the highest muscle activation (p=0.02) for manual cases as compared to automated cases. The remainder of the surgeons showed similar levels of activation for both groups. The study shows how surface EMG can be used to characterize surgeon-specific surgical strategy to inform on surgeon’s wellbeing and longevity, and indicate that intensity is affecting surgeons’ performance, resulting in muscle fatigue, suggesting that to reduce muscle fatigue, a consistent lower intensity should be maintained during impaction steps.

Statement of Clinical Significance

This study shows that surface EMG data were able to discern patterns of muscle activation between surgeons, impaction modalities and specific tasks during the case. This study suggests methodology that can be used to review the effort required during THA and the surgeon’s level of fatigue. Ultimately, this study provides useful insights into how use of an automated impactor for femoral broaching could reduce the effort required during THA and lessen fatigue for orthopaedic surgeons.

Keywords: Automation; Electromyography; Muscle Fatigue; Total Hip Arthroplasty

Introduction

Orthopaedic surgeons perform physically demanding and repetitive tasks during surgery. The occupational hazards [1-4], risk of burnout [5-7], ergonomic factors related to risk of injury [8-11] and fatigue [12] associated with orthopaedic surgery have been well documented in the literature, and work-related musculoskeletal disorders and injuries have been shown to be a leading cause of injury and absenteeism [13]. A recent study also showed that one hundred percent of surveyed orthopaedic surgeons who had been in practice between 21 and 30 years reported some form of musculoskeletal overuse disorder. Shoulder overuse disorders (rotator cuff disease, biceps tendonitis, and other tendinopathies) were the most common reported injuries for adult reconstructive surgeons [4]. Research has also been conducted to explore the relation of case-order in total joint replacement and patient complications [14]. In primary Total Hip Arthroplasty (THA), a mallet is traditionally used for multiple steps in the procedure: femoral broaching, stem insertion, cup impaction, and impaction of head onto stem. It is estimated that a surgeon may swing a mallet as many as 300 times during each case [2], and 12 ± 9 times for each femoral broach [1].A surgical automated impactor was developed to automate impaction steps in THA procedures.

A potential benefit of this technology is the ability to reduce surgeon muscle fatigue, and over time, reduce the risk of surgeon injury for orthopaedic surgeons. The impactor’s effect on the surgeon’s muscle fatigue has been investigated in simulated broaching [15] duringTotal Hip Arthroplasty(THA) with the use of Surface Electromyography (sEMG). Results from this study showed that a group of surgeons performing a set of impactions in a lab-controlled setup had significantly lower levels of muscle fatigue compared to manual impactions. However, this has not yet been evaluated in real-life THA procedures.Muscle fatigue is a result of an intensive activity maintained over time and at a high effort. However, effort is user dependent [16]. Factors contributing to fatigue include posture, strategy, force, stature, training level, type of contraction (e.g eccentric, concentric) and is a result of the relationship between power and duration [17].

In addition, motivation, physical fitness, nutritional status, and the types of motor units (i.e., fibres) recruited based on the intensity and duration of activity have an impact on the user’s performance. An increase in muscle activation is the result of a progressive increase in muscle fiber recruitment, with attempt to complete a given task, and muscle fiber fatigue results in an inability to produce the same force level [18]. For this reason, a change in muscle activation at surgical steps of interest, can be used to characterize the effect on the user of the specific workflow. On the contrary, a decrease, or no change in muscle activation can suggest that muscles can maintain the required force. For these reasons, when muscle fatigue is investigated in a real-world environment, all these factors should be considered, and analysis should be performed focusing on identified workflow steps and user-specific analysis.Therefore, the aim of this study was to quantify changes in muscle activation during manual and automated THA workflows to characterize surgeon specific performance, by means of EMG. Our hypothesis was that 1) increased muscle activation would be seen in manual broaching compared to automated broaching across the surgeons being studied; and 2) different surgeons would have different patterns of muscle activation depending on their broaching position or style.

Methods

Level of Evidence: II

As part of a prospective, Randomized, Controlled Trial (RCT), four male orthopaedic surgeons performed 77 direct anterior approach THA cases randomized into two groups:39 automated impaction cases (KINCISETM; DePuy Synthes, Warsaw, IN, USA) in the study group, and 38 manual impaction cases in the mallet control group. Cases were performed at different locations over a period of 2 years (2019-2021).The trial is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04191733). Patients and surgeons provided signed consent to participate and Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was in place for the duration of the study. For one patient only, osteoporotic bone was reported (DORR Class C), whereas the remainder of cases reported bone quality rated between Good and Normal (DORR Class A and B). Two cases reported calcar fracture. To record data on muscle performance, sEMG signals were collected using a compression shirt (Athos, Mad Apparel, Inc.) containing built-in surface electrodes situated over various muscle groups, including bilateral Biceps Brachii (RBB, LBB),Anterior Deltoid (RAD, LAD), Latissimus Dorsi (RLD, LLD), Triceps Brachii (RTB, LTB) and Pectoralis (RP, LP) muscles. During each case, surgeons wore the Athos shirt underneath the scrubs to allow the electrodes to be in direct contact with the muscle compartments identified (Figure1).

Figure 1: Athos T-shirt with surface EMG sensors embedded

Surface EMG data was recorded uninterruptedly for the entirety of each case. The time corresponding to the start and end of broaching and start and end of the procedure were collected and saved separately.Data provided from Athos was already pre-conditioned and in the form of sEMG Root Mean Square (RMS) envelopes. For this study, each envelope was then segmented by extracting burst of activity corresponding to four time points: 1) start of the procedure, 2) start of broaching, 3) end of broaching and 4) end of the procedure. The average amplitude was then quantified for each time point, to investigate the trend over time and changes of muscle activation in the automated and manual groups during THA. Data analysis was performed with MATLAB (Mathworks, Inc).EMG average lower than noise level (~30µV) were discarded from statistical analysis. Together with quantitative data, qualitative data, in the form of a questionnaire, and pictures of surgical ergonomic form were gathered from the group of surgeons. The questions focused on personal strategy in performing manual and automated THA, such as the posture used during both workflows, whether there were sensations of fatigue, and the percentage of manual and automated cases. The answers of the questionnaire are reported in the results section.Statistical analysis was performed to investigate the difference in muscle activation features (number of muscles recruited and amplitude of active muscles) as a way of describing muscle fatigue and the strategies adopted by a group of orthopaedic surgeons. This was performed with an ANOVA General Linear Model (Minitab 18, Statistical Software (2010). State College, PA: Minitab, Inc.), where the response was set as RMS values and fixed factors set as modalities (automated, manual), muscles and surgeons. The confidence level was α<0.05. To discern surgeons’ strategy and surgical ergonomic effect on performance, results are presented for each surgeon to identify the number of muscles with highest activation for each workflow at each stage.

Patient and Surgeon Demographics

Osteoporotic bone was reported for one patient (DORR Class C; automated), whereas the remainder of cases reported bone quality rated either Good or Normal. DORR class was A in 32 patients, B in 43, and C in 2. One case reported calcar fracture in the manual group. Patient demographic data were not different between groups (Table 1). (Surgeon 1) reported previous history of musculoskeletal injury at the time of the clinical trial (shoulder scope decompression for subacromial impingement).

|

Manual |

Automated |

p-value |

|

|

Patient Age (years) |

64.68 (43-85) |

64.64 (44-83) |

0.98 |

|

Mean (range) |

|||

|

Patient Gender |

Female: 55.26% |

Female: 51.28% |

0.82 |

|

n (%) |

Male: 44.74% |

Male: 48.72% |

|

|

Patient BMI |

27.76 (19.7-39.2) |

27.28 (21.8-38.9) |

0.64 |

|

Mean (range) |

|||

|

Primary Diagnosis |

OA: 34 (89.47% |

OA: 38 (97.44%) |

0.2 |

|

n (%) |

AVN: 4 (10.53%) |

AVN: 1 (2.56%) |

|

|

Patient ASA Class |

I: 1 (2.63%) |

I: 3 (7.69%) |

0.23 |

|

n (%) |

II: 23 (60.53%) |

II: 28 (71.79%) |

|

|

III: 14 (36.84%) |

III: 8 (20.51%) |

Table 1: Patient characteristics Results

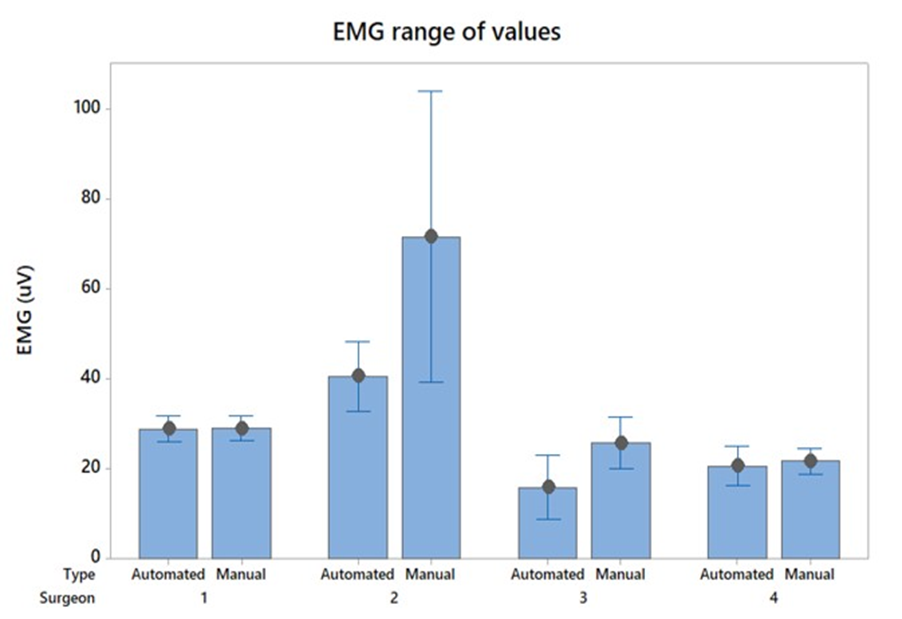

The answers to the questionnaire completed by surgeons are summarized in (Table 2). Surgeons recruited muscle compartments at different intensities. (Figure 2) shows the difference in muscle activation between automated and manual cases. Statistical significance was observed for Surgeon 2 (p=0.02). Both (Surgeon 3 and 4) showed higher activation for manual cases at different degrees but without statistical significance.

|

Surgeon 1 |

Surgeon 2 |

Surgeon 3 |

Surgeon 4 |

|

|

Height |

73 inches |

75.5 inches |

70 inches |

71 inches |

|

Handedness |

Right |

Right |

Right |

Right |

|

Feel less fatigued after automated cases compared to manual? |

Absolutely yes |

Hard to say, it depends on what case number it is. Most surgeons are more likely to be more tired at the end of the day especially after 6-7 cases |

No |

Yes |

|

If you have fatigue, where do you most feel it? |

Mostly anterior shoulders |

Hard to say, but if any, it would be shoulder and forearm. |

No noticeable sensations of fatigue during a THA |

Shoulder and forearm |

|

Do you find you need more recovery after manual cases compared with automated cases? |

Yes |

Unsure |

No |

No extra time to recover between cases, however more effort expended is noticeable. |

|

Use a footstep to perform surgery? |

No |

No |

Yes, and used for study cases |

Always use a footstep for broaching manual and with KINCISE |

|

Any adjustments needed in OR environment? |

Raise, lower, airplane, and Trendelenburg the table throughout the case at different times to achieve an ergonomic position |

Lower the OR bed when broaching the femur |

No |

Raise the bed for broaching the femur to allow the foot to drop |

|

Stand above or below the incision during impaction |

Below |

Above |

Above |

Above |

Table 2: Surgeon Details

Figure 2: Range of muscle activation for each surgeon for manual cases and automated cases (statistically significant difference noted for Surgeon 2 (p<0.001)).

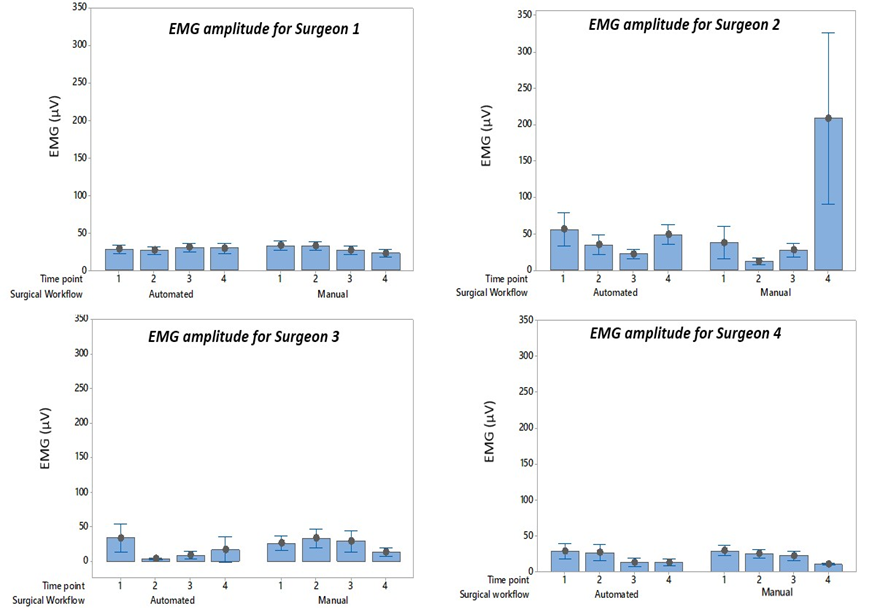

In terms of differences over time, (Figure3) shows that for Surgeon 1, 3 and 4 statistical significance is not observed over time, however differences in activation were observed. Surgeon 3 shows a decrease in muscle activation for automated cases during broaching (time point 2 and 3) and an increase in muscle activation during manual broaching. For manual cases, similar muscle activation was observed for Surgeon 1 (p=0.463), 3 (p=0.110) and 4 (p>0.05), however Surgeon 2 showed the highest muscle activation and it presented at the end of the procedure (p<0.001).

Figure 3: Range of muscle activation for each surgeon for manual and automated cases for each time point (statistically significant higer muscle activation at the end of the surgery for Surgeon 2 (p<0.001)).

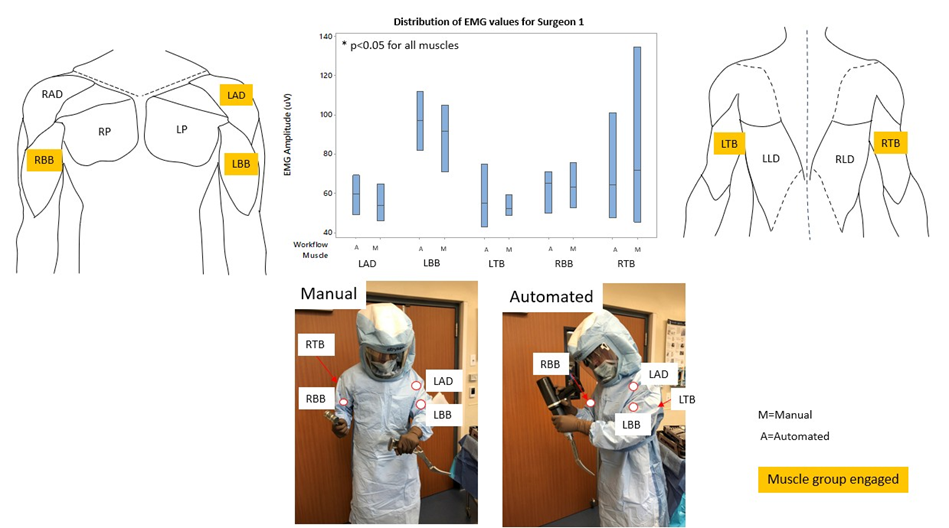

As shown in (Figure 4), no difference was observed for Surgeon 1 between manual and automated cases (p=0.365). However, LAD, LBB, RBB, RTB, and LTB, showed the highest average muscle activation (p<0.001).

Figure 4: Surgeon 1 summary results (*denotes significant difference).

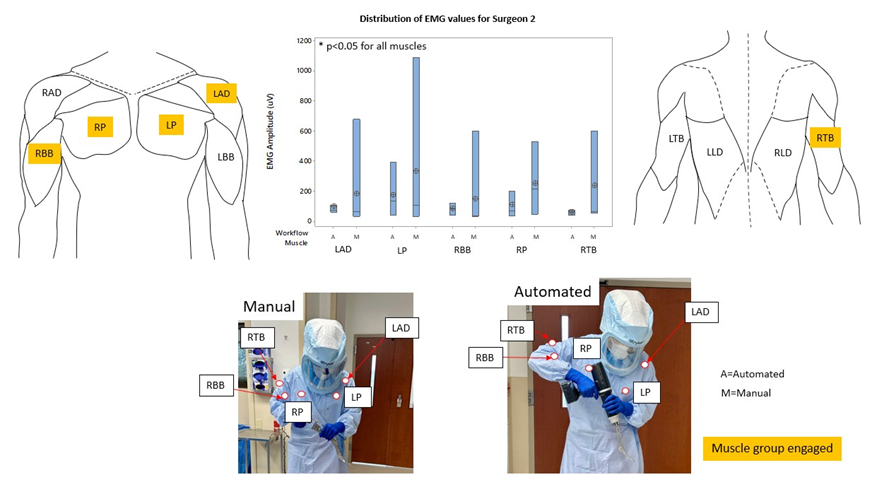

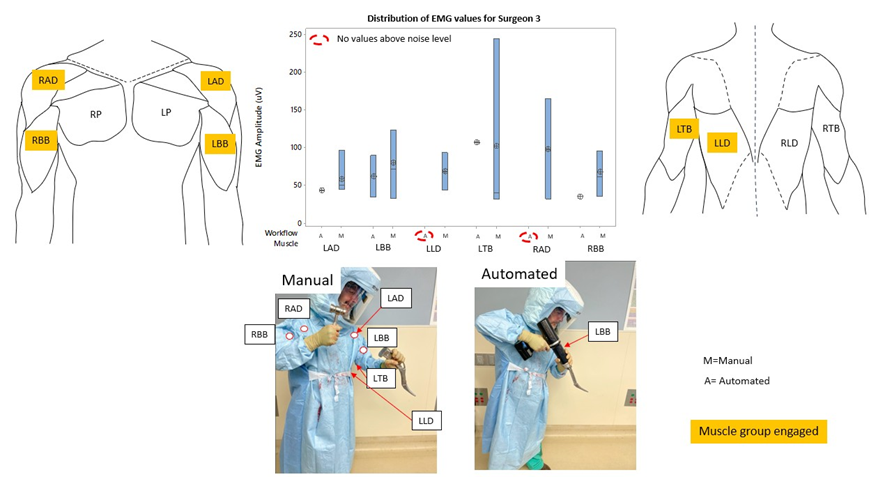

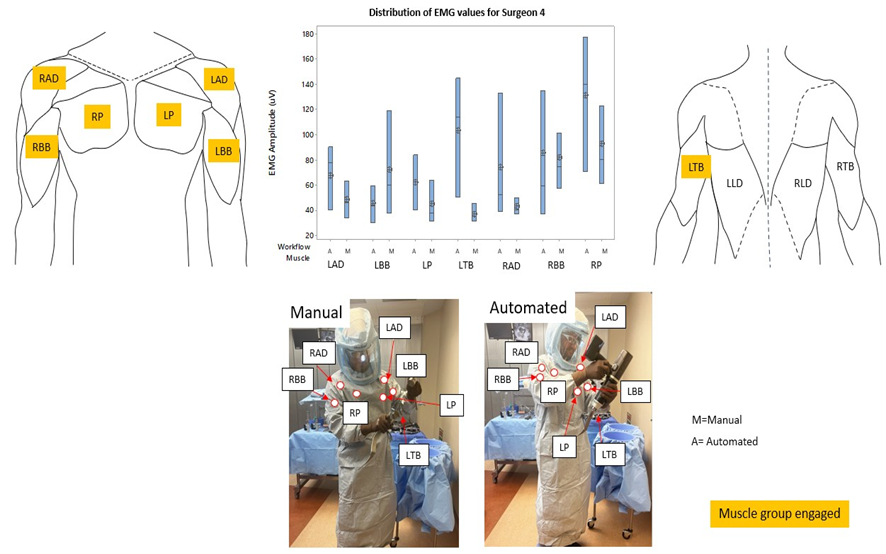

Figure 5: Surgeon 2 summary results (*denotes significant difference). (Figure 5) shows (Surgeon 2) presenting significantly higher muscle activation for manual cases (p<0.0001).Muscles with highest muscles activation for manual cases (p=0.008) were LAD, LP, RBB, RP and RTB. Surgeon 3 (Figure 6) showed statistically significant higher muscle activation was observed for manual cases (p=0.023) for LAD, LBB, RBB, RAD and LLD. LTB showed the highest activation for both groups, with no statistical difference (p>0.05) between manual and automated cases. Overall, (Surgeon 3) showed lower levels of muscles activation, resulting in 4 out of 10 muscle compartments discarded from analysis (EMG amplitude lower than noise level). For automated cases, LAD, LLD and RBB muscle activation was higher than the noise level for one case only, as shown in (Figure 6) by the crossed circle.As shown in (Figure 7), muscle activation data for (Surgeon 4) showed similar range values for muscle activation with no overall statistical significance. For manual cases, LBB showed the highest muscle activation, with no statistical difference (p=0.140). Highest muscle activation was observed for automated cases, specifically for LAD, LP, LTB, RAD, RBB and RP, with statistical difference only for RBB (p<0.01), with average muscle activation ranging between 62.3 uV and 131.2 uV.

Figure 6: Surgeon 3 summary results (*denotes significant difference).

Figure 7: Surgeon 4 summary results (*denotes significant difference).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to use EMG data in a prospective RCT to characterize surgeon-specific muscle activation, by describing which muscles were recruited, their magnitude, and any changes in muscle activation over time and between workflows. Recent studies have shown that orthopaedic surgeons are affected by a series of occupational injuries, including musculoskeletal disorders, due to the use of tools, exertion of force in non-ergonomic positions, and general manipulation of heavy limbs that is often required [19,20]. EMG has been employed previously to discern between device designs [21-23], operating room ergonomics [24], to identify the effect of operating time [25], and to quantify muscle fatigue [26] for laparoscopic surgery. Muscle activation information has been used to distinguish details on surgeons’ skills level, experience and performance, and as a reliable tool to measure for physiological stress detection [27]. However, performance of surgical tasks and fatigue can be related to high stress, muscular workload and variability in surgical task performance. Therefore, it was deemed important to highlight surgeon-specific trends, to be able to provide insights into what factors of a surgical workflow affect surgeons. This study demonstrates that sEMG data can discern patterns of muscle activation between surgeons, impaction modality and specific time points within the procedure. For the manual cases, results are in line with what was observed in a lab-based study [15], with higher activation observed in the Biceps Brachii (left or right) involved in swinging the mallet. Although posture doesn’t differ dramatically, (Surgeon 2) showed the highest activation, with significant change across time points, with highest activation at the end of manual cases. This might have been a consequence of a higher intensity broaching strategy applied by (Surgeon 2) which, over-time, would increase muscle fatigue. Since muscle fatigue occurs because of an intense activity maintained or repeated over time, this trend in muscle activation suggests muscle fatigue. It was noted that the higher muscle activation at the end of the surgery was observed for all manual cases included in the analysis.Another factor affecting muscle performance is posture. (Surgeon 1) reported specific attention to posture during surgical workflows (e.g., keeping arms close to torso to reduce fatigue and changing operating room ergonomics). This may have affected the magnitude of muscle activation, leading to no significant change in muscle recruitment and therefore no observation of onset of fatigue at the end of the surgery for manual or automated cases. Similarly to (Surgeon 1, Surgeon 3) did not show significant difference in muscle activation and changes between groups, having the lowest overall muscle activation, and activation of only a few muscle compartments with no activation above noise level. Overall, the level of activation for (Surgeon 1 and 3) suggests that the intensity of the tasks performed was not enough for muscle fatigue to occur, potentially due to the individual surgeon attention to posture and/ or ergonomics through manual and automated cases. For (Surgeon 4), manual broaching was performed with the left arm performing impactions, with the highest activation for BB, AD, Pectoralis and TB, similar to what was observed for (Surgeon 1-3) on the right side. Muscle activation was the lowest for manual cases, which was observed both in muscle compartment activation and between time points through THA workflows. For the automated cases, all surgeons engaged the right arm to trigger the automated device, resulting in highest activation for BB, AD and Pectoralis, whereas the left arm held the device, with TB and BB showing the highest activation. Overall, muscle activation was lowest for automated cases. Surgeon 3 showed no activation above the noise level during broaching for the automated cases, suggesting minimal engagement of muscle compartments. Results therefore seem to suggest that the use of an automated device doesn’t add burden to surgeons with a low level of activation but reduces muscle fatigue for surgeons with fatigue-inducing muscle activation (Surgeon 2).In summary, for the group of cases included in this study, three out of four surgeons showed an average level of activation, suggesting low intensity tasks. Our results seem to suggest that the applied postures are not causing fatigue within the surgical workflow. We observed that for this sub-group of surgeons, the task was not intense enough to induce fatigue. For one surgeon, although posture was similar to the others, results seem to suggest that tasks were performed at higher intensity (highest muscle activation), which ultimately resulted in a significant increase in muscle activation toward the end of the surgery for manual cases.

This phenomenon suggests that as muscles fatigue, more motor units are recruited to try and sustain the same effort, resulting in higher muscle activation.Recent studies have shown decreased energy expenditure and improved ergonomics with use of automated impaction. Coden, et al. [28] reported increased energy expenditure and decreased heart rate with use of automated impaction. Vandeputte, et al. [29] reported decreased hormonal stress levels and lower physical and cognitive exhaustion with improved ergonomics for an experience orthopaedic surgeon with use of an automated impactor. It could be interesting to compare muscle activation patterns and measurements of energy expenditure and measures of physical and cognitive stressors. If automated broaching proves to help reduce physical and mental fatigue, it could help alleviate some of the concerns with case load and the possibility for increased complications with later cases, musculoskeletal injuries for orthopaedic surgeons, and surgeon burnout.It is important to note that this study presents limitations.

The number of surgeons is limited. To start identifying patterns, more participants would need to be included. In addition, a diverse population would highlight differences that could potentially drive insights into how automated impaction is supporting groups of surgeons with a wider spread of anthropometric features (e.g., small stature surgeons), that could potentially benefit more from the use of an automated device. In addition, a limited number of surgeons does not allow for differentiation between different surgical techniques, which would potentially highlight differences between manual and automated cases.Further study should include recruitment from a larger pool of surgeons, to include different subgroups for comparison, to be able to identify grouped patterns as measurable metrics that can be utilized to improved surgical performance. In addition, the application of sEMG measurements for different surgeries (e.g. Total Knee Arthroplasty) could identify surgical procedure more prone to fatigue and/or injury, and therefore to target to improve the technique or strategies. Nevertheless, results from this study showed how evaluating surgeons’ performance can highlight differentiation in muscle recruitment strategies and effort (activation amplitude) and, therefore, help drive changes to improve resilience and wellbeing. Conclusion

The present study showed how sEMG can be used to characterize surgeon-specific surgical strategy to inform on surgeon’s wellbeing and longevity. Results showed that intensity is affecting surgeons’ performance, resulting in muscle fatigue, suggesting that a consistent lower intensity should be maintained during impaction steps. Alternatively, as per Surgeon 1 survey answer:“continuously changing the room ergonomics might help in supporting surgeons’ ergonomics and reduce the likelihood of fatigue.” From literature it is known that orthopedic surgery is one of the most physically demanding specialties, therefore it is fundamental to understand what can be done to support surgeons’ performance. The authors would recommend use of automated impaction as a strategy to reduce fatigue and the physical burden of impaction steps in primary THA. The information presented in this study is a first step in understanding which features of surgical ergonomics, device design and task performance are impacting the wellbeing and longevity of orthopaedic surgeons.

Acknowledgements: This study was funded by DePuy Synthes. EF, DF, and LG are or were employees of DePuy Synthes. DF owns Johnson & Johnson stock. HCT has been a paid presenter for Heron Therapeutics, received research support from DePuy Synthes and is or has been a board member or has received committee appointments from Southern Orthopaedic Association. CY receives royalties from Zimmer Biomet, has been a paid speaker for DePuy Synthes, Ethicon, Medtronic and Stryker, a paid consultant for DePuy Synthes and Stryker, and has received research support from DePuy Synthes and United Orthopedics. JCM has been a paid speaker for DePuy Synthes, a paid consultant for DePuy Synthes and HealthTrust, has received research support from DePuy Synthes, Biomet and Exactech, Inc., and has been a board member or has received committee appointments from the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons. BPG is a paid consultant for DePuy Synthes, has received research support from DePuy Synthes, is on the editorial/governing board at Journal of Arthroplasty, and has been a board member or has received committee appointments from the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons.

References

- Alqahtani SM, Alzahrani MM, Tanzer M (2016) Adult Reconstructive Surgery: A High-Risk Profession for Work-Related Injuries. J Arthroplasty 31: 1194.

- Canoles HG,Vigdorchik JM (2022) Occupational Hazards to the Joint Replacement Surgeon: How Can Technology Help Prevent Injury? J Arthroplasty 37: 1478-1481.

- Ryu RC,Behrens PH,Malik AT,Lester JD,Ahmad CS (2021) Are we putting ourselves in danger? Occupational hazards and job safety for orthopaedic surgeons. J Orthop 24: 96-101.

- Vajapey SP, Li M, Glassman AH (2021) Occupational hazards of orthopaedic surgery and adult reconstruction: A cross-sectional study. J Orthop 25: 23-30.

- Arora M, Diwan AD, Harris IA (2013) Burnout in orthopaedic surgeons: a review. ANZ J Surg 83: 512-515.

- Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps GJ, Russell T, Dyrbye L, et al (2009) Burnout and career satisfaction among American surgeons. Ann Surg 250: 463-471.

- Travers V (2020) Burnout in orthopedic surgeons. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 106: S7-S12.

- Aaron KA, Vaughan J, Gupta R, Ali NE, Beth AH, et al. (2021) The risk of ergonomic injury across surgical specialties. PLoS One 16: e0244868.

- Kant IJ, de Jong LC, van Rijssen-Moll M, Borm PJ (1992) A survey of static and dynamic work postures of operating room staff. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 63: 423-428.

- McQuivey KS, Christopher ZK, Deckey DG, Mi L, Bingham JS, et al. (2021) Surgical Ergonomics and Musculoskeletal Pain in Arthroplasty Surgeons. J Arthroplasty 36: 3781-3787.

- Scheidt S, Ossendorf R, Prangenberg C, Wirtz DC, Burger C, et al.(2022) The Impact of Lead Aprons on Posture of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Z Orthop Unfall 160: 56-63.

- Peskun C, Walmsley D, Waddell J, Schemitsch E (2012) Effect of surgeon fatigue on hip and knee arthroplasty. Can J Surg 55: 81-86.

- Epstein S, Sparer EH, Tran BN, Ruan QZ, Dennerlein JT, et al. (2018) Prevalence of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders Among Surgeons and Interventionalists: A Systematic Review and Metaanalysis. JAMA Surg 153: e174947.

- Li X, Zhang Q, Dong J, Zhang G, Chai W, et al. (2018) Chen J. Impact of surgical case order on peri-operative outcomes for total joint arthroplasty. Int Orthop 42: 2289-2294.

- Ferrari E, Khan M, Mantel J, Wallbank R (2021) The assessment of muscle fatigue in orthopedic surgeons, by comparing manual versus automated broaching in simulated total hip arthroplasty. Proc Inst Mech Eng H 235: 1471-1478.

- Enoka RM, Duchateau J (2008) Muscle fatigue: what, why and how it influences muscle function. J Physiol 586: 11-23.

- Poole DC, Burnley M, Vanhatalo A, Rossiter HB, Jones AM (2016) Critical Power: An Important Fatigue Threshold in Exercise Physiology. Med Sci Sports Exerc 48: 2320-2334.

- Emam TA, Frank TG, Hanna GB, Cuschieri A (2001) Influence of handle design on the surgeon’s upper limb movements, muscle recruitment, and fatigue during endoscopic suturing. Surg Endosc 15: 667-672.

- Yakkanti RR, Sedani AB, Syros A, Aiyer AA, D’Apuzzo MR, et al. (2023) Prevalence and Spectrum of Occupational Injury Among Orthopaedic Surgeons: A Cross-Sectional Study. JB JS Open Access 8: e22.00083.

- Lester JD, Hsu S, Ahmad CS (2012) Occupational hazards facing orthopedic surgeons. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 41: 132-139.

- Berguer R, Gerber S, Kilpatrick G, Beckley D (1998) An ergonomic comparison of in-line vs pistol-grip handle configuration in a laparoscopic grasper. Surg Endosc 12: 805-808.

- Steinhilber B, Seibt R, Reiff F, Rieger MA, Kraemer B, et al. (2016) Effect of a laparoscopic instrument with rotatable handle piece on biomechanical stress during laparoscopic procedures. Surg Endosc 30: 78-88.

- Emam TA, Frank TG, Hanna GB, Stockham G, Cuschieri A(1999) Rocker handle for endoscopic needle drivers. Technical and ergonomic evaluation by infrared motion analysis system. Surg Endosc 13: 658661.

- Berquer R, Smith WD, Davis S(2002) An ergonomic study of the optimum operating table height for laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc 16: 416-421.

- Slack PS, Coulson CJ, Ma X, Webster K, Proops DW (2008) The effect of operating time on surgeons’ muscular fatigue. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 90: 651-657.

- Yoon SH, Jung MC, Park SY (2016) Evaluation of surgeon’s muscle fatigue during thoracoscopic pulmonary lobectomy using interoperative surface electromyography. J Thorac Dis 8: 1162-1169.

- Soangra R, Sivakumar R, Anirudh ER, Reddy YS, John EB (2022) Evaluation of surgical skill using machine learning with optimal wearable sensor locations. PLoS One 17: e0267936.

- Coden G, Greenwell P, Niu R, Fang C, Talmo C, et al. (2023) Energy expenditure of femoral broaching in direct anterior total hip replacements-Comparison between manual and automated techniques. The International Journal of Medical Robotics and Computer Assisted Surgery: e2592.

- Vandeputte F-J, Hausswirth C, Coste A, Schmit C, Vanderhaeghen O, et al. (2023) The Effect Of Automated Component Impaction On The Surgeon’s Ergonomics, Fatigue And Stress Levels In Total Hip Arthroplasty. Journal of Orthopaedic Experience & Innovation 2023.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.