Cervical Ectopic Pregnancy of an Invasive Partial Mole: A Case Study and Literature Review

by Suzan Alshdefat1*, Yazan Mahafza2, Rana Alshdaifat3

1Consultant Obstetrics, Gynecology and Gyn-Oncology, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Ain Alkhaleej Hospital, Al Ain, United Arab Emirates

2Supermicrosurgery & Lymphatic Reconstruction Research Fellow, Department Of Plastic Surgery, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Ohio, USA

3Full Time Lecturer, Adult Health Nursing, Princess Salma Faculty of Nursing, Al Albayt University, AL Mafraq, Jordan

*Corresponding Author: Suzan Alshdefat, Consultant Obstetrics, Gynecology and Gyn-Oncology, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Ain Alkhaleej Hospital, Al Ain, United Arab Emirates

Received Date: 03 December 2025

Accepted Date: 09 December 2025

Published Date: 11 December 2025

Citation: Alshdefat S, Mahafza Y, Alshdaifat R (2025) Cervical Ectopic Pregnancy of an Invasive Partial Mole: A Case Study and Literature Review. Ann Case Report. 10: 2469. https://doi.org/10.29011/2574-7754.102469

Abstract

Hydatid form molar pregnancy in the cervix is extremely uncommon but can be fatal with incorrect diagnosis or delayed treatment. We review diagnostic approaches and evaluate treatment modalities in light of increasing awareness of the condition and the therapeutic challenges it presents. Chemotherapy—single or multiple agents depending on stage and score is the standard of care, while hysterectomy remains an option for patients who do not desire fertility. A 48-year-old woman presented with vaginal bleeding and abdominal pain after amenorrhea. Transvaginal ultrasound identified a cervical cystic lesion, and histopathology confirmed an invasive cervical partial mole. Dilatation and curettage were performed, and serial β hCG measurements revealed a steady decline without the need for methotrexate or adjuvant chemotherapy. Due to limited early surveillance, morbidity was increased. The patient was successfully managed and remained disease free thereafter.

Keywords: Molar Pregnancy; Ruptured, Invasive; Cervical Ectopic Pregnancy; Uterine Cervix; Hydatidiform Mole; Hcg - Human Chorionic Gonadotropin.

Introduction

Gestational trophoblastic illness is a trophoblastic cell proliferation problem. It refers to a collection of interconnected lesions that arise from the placenta's trophoblastic epithelium. It is a heterogeneous set of lesions with distinct etiology, morphologic features, & clinical characteristics. Complete & partial hydatiform moles, invasive moles, choriocarcinoma, placental spot trophoblastic tumor, epithelioid trophoblastic tumor, extravagant placental position, and placental nodule are all categorized as gestational trophoblastic illness by the World Health Organization. (WHO) [55]

About 400 BC, Hippocrates, in his report of uterine dropsy, was likely the first to mention gestational trophoblastic illness. Marchand was the first to link a hydatidiform mole to pregnancy in 1895, notwithstanding subsequent observations. [63] Trophoblastic tissue invades the endometrium aggressively & forms a rich uterine vascular, forming the placenta, an intimate link between the fetus and the mother. Healthy trophoblast may be found in the maternal circulation using PCR, which is one of the distinguishing markers of malignant illness. [64] The placenta is the source of all gestational trophoblastic illness. The ability to accurately quantify hCG is critical for the treatment of gestational trophoblastic illness, various malignancies, and pregnancy. [65]

Molar pregnancy occurs when an aberrant ovum fails to fertilize properly, resulting in the pregnancy. [11] The karyotype of whole moles is 46,XX, The molar chromosomes, on the other hand, are exclusively inherited from the paternal.[13] The vast majority of complete moles are homozygous, also they appear to rise from an anuclear void ovum fertilized with a haploid (23X) sperm, that further replicates its own chromosomes. [14] Mitochondrial DNA is of maternal origin, whereas the entire mole's chromosomes are of paternal origin. [15] It can also happen when two sperm fertilize a haploid ovum, or when one sperm replicates its DNA, leading in a partial molar pregnancy. There are no recognizable embryonic or fetal tissues in whole moles. Villous trophoblast gives rise to hydatidiform moles and choriocarcinoma, while interstitial trophoblast gives rise to placental-site trophoblastic tumors. Even though investigative criteria have evolved since evacuation is performed in former pregnancy, most whole and partial hydatidiform moles exhibit distinct morphological characteristics. [65] The chorionic villi of a partial hydatidiform mole differ from those of a complete mole in that they have different sizes and are marked by focal inflammation & focal trophoblastic hyperplasia; focal, slight atypia of trophoblasts on implant location; distinguished villous scalloping & prominent stromal trophoblastic inclusions; as well as noticeable foetal or embryonic tissues. [11,16] Complete hydatidiform moles develop more slowly than partial hydatidiform moles and occur later in the first or early second trimester, yet they can still cause vaginal bleeding or incomplete miscarriages. [66, 67] Gross morphologic and histological investigation, as well as chromosomal pattern, can separate these two entities, partial and complete moles. Chorionic villi abnormalities such as diffuse trophoblastic hyperplasia and generalised swelling, as well as diffuse, substantial atypia in the trophoblast at the infection site, distinguish it histologically. [16]

Patients with a partial mole frequently have clinical manifestations of a missed or incomplete abortion, which including vaginal bleeding, high -HCG levels (>100000 mIU/ml), Rather with the usual criteria of a complete mole, a complete mole has a uterine size that is small or adequate for gestational age. [18, 19] The rise in HCG titer is a laboratory test used to diagnose invasive mole in molar pregnancy follow-up. Though histopathology is essential for a confirmed detection of an invasive mole [61], HCG or radiologic imaging could also be used to identify invasive moles. [62] Following an exhaustive investigation, Fowler determined that normal pre-evacuation ultrasonography scanning misses less than half of all hydatidiform moles. Furthermore, the detection rate for entire moles is higher than partial moles, and it improves after 14 weeks of pregnancy. [29] Maternal age, previous molar pregnancy history, smoking, alcohol usage, and oral contraceptives are all risk factors for hydatiform molar pregnancy. [32, 33]

Ectopic pregnancy occurs when the growing blastocyst is implanted somewhere else than the uterine cavity's lining. Ectopic pregnancy occurs in 6 to 16 percent of women who visit OPD department with first-trimester bleeding, discomfort, or both [30]. According to recent national records from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, general prevalence of ectopic pregnancy increased from the mid-twentieth century to the early 1990s, plateauing at roughly 20 per 1000 pregnancies. Prior ectopic pregnancies, tubal illness and operation, in-utero DES exposure, past diseases, implants, impotence, varied sexual partners, smoking, in vitro fertilization (IVF), vaginal douching, and ageing are all recognized ectopic pregnancy risk factor. [31]

In cervical pregnancy, which is an ectopic pregnancy, the trophoblast implantation inside the cervical tissue of the endocervical canal. [17] Ectopic pregnancy in the cervix is an extremely uncommon occurrence. Cervical ectopic pregnancies account for much less than 1percentage points among all ectopic pregnancies and have a risk of occurring one in 2500 to one in 18,000 times. [20, 21] People having this type of ectopic pregnancy have a high threat of life-threatening haemorrhage because to the erosion of cervical blood arteries, which was previously treated with hysterectomy. Vaginal bleeding without discomfort after a period of amenorrhea, as well as cervical elongation and unstiffening, are all symptoms of cervical ectopic pregnancy, especially if diagnosis is delayed. [22]

Because of enhanced ultrasound resolution and previous diagnosis of abnormal pregnancies, more conservative treatments have been developed to reduce morbidity and fertility protection. Given the condition's infrequency, even today, the most effective form of treatment is being researched. In the past, conservative care of this illness has only been successful in around half of the instances. Pregnancies following cervical pregnancy are thus uncommon, and only a handful have been recorded in the literature, making it difficult to quantify the risks of such pregnancies. [23]

The cause of the most of instances is uncertain. Abortions in the past, uterine curettage, prior Cesarean section, & IVF treatment by embryo transfer have all been identified as hazardous factors in the literature. Two of the most common causes of cervical ectopic pregnancy are a record of uterine curettage and IVF. [22, 23]

Raskin presented the first ultrasound description of cervical pregnancy in 1978, and since then, ultrasound has enhanced the potential for early detection, resulting in a significant reduction in problems and maternal mortality and morbidity. Ultrasound was already utilized to distinguish between cervical pregnancy & the cervical phase of miscarriage. [24]

Cervical pregnancy was difficult to diagnose before the introduction of ultrasonography (US), and was frequently diagnosed post hysterectomy for uncontrolled bleeding. [25, 27], allowing for more conservative treatments that protect the uterus. Surgical intervention has traditionally been used to treat cervical ectopic pregnancies. The most common treatment is hysterectomy. This method results in the loss of reproductive potential. In nonsurgical therapy, a combining of pharmacological and interventional methods is usually used. Methotrexate, mifepristone, as well as misoprostol are all used to effectively treat cervical ectopic pregnancy. Other studies have combined medicinal therapy with uterine artery embolization to reduce the risk of complications like bleeding or have used ultrasound guidance to inject methotrexate or (KCl) directly into the gestational sac or the fetus. [26, 27].

Only 5 occurrences of molar pregnancy presenting as cervical ectopic have been documented in the literature. The presenting symptom in all of the instances was vaginal bleeding, and the patients ranged in age from 25 to 53. Despite the fact that the treatment methods differed, all of the patients were able to attain complete remission. [24]

Case Presentation

A 48-year-old female, G7 P4 A2, otherwise healthy was referred at 3 weeks gestation with a history of normal regular periods. She was not using any contraception. Her last pregnancy was 7 years ago, and she is married to a 55-year-old healthy male. After 14 days of amenorrhea, she presented to our gynecological emergency clinic with 3 weeks of persistent mild to severe vaginal bleeding and stomach discomfort. She didn't have any shoulder ache. Her previous medical and surgical history was unremarkable. She was a nonsmoker with no ailments.

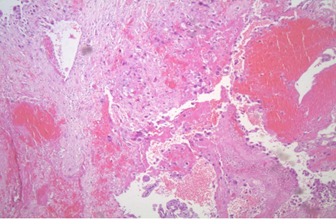

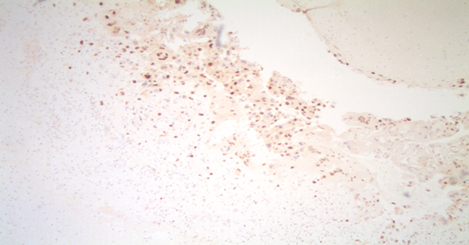

Upon arrival the patient was awake, alert and conscious. On admission and examination her vital status and general condition were poor showing blood pressure 110/76, heart rate was 82 bpm, respiratory rate was 17, and a general exam revealed no significant findings or abnormalities. Ultrasound examination was performed trans-abdominally which showed an empty uterus and a cervical cystic lesion containing a solid component about 4 cm in diameter. Genital exam showed normal looking vulva and vagina. A vaginal speculum exam showed a ruptured thin walled cystic lesion over the inner surface of the anterior cervical lip. The Quantitative human chorionic gonadotrophin BHCG titer in the emergency department was 12,300 mIU/mL, and her HB level was 10.8 g/dl. All of the tests for renal and liver function were within standard limit. She was resuscitated with intravenous fluid. After resuscitation she was sent to perform dilatation & curettage (D&C) and biopsy of the cervical lesion and the specimen sent for histopathology .The result of the histopathology was ectopic cervical invasive mole, partial type (Figure 1) and (Figure 2) & the endometrium showed decidual reaction of pregnancy. The hCG level declined rapidly postoperatively.

Figure 1: Histopathological findings of the site of direct cervical stromal invasion, without decidual and implantation site reaction.

Figure 2: P57 immunostaining is positive in both stroma and cytotrophoblasts, which indicates a partial molar pregnancy.

Managment and Follow Up

After counseling the patient, with informed consent for a total abdominal hysterectomy. Then the patient underwent hysterectomy as a life saving measure, because of worsening abdominal pain and hemoperitoneum. Without taking methotrexate, the BHCG level reduced to 50 mIU/ml 3 weeks after surgery, whereas six weeks later, the BHCG result was normal. 4 months following hysterectomy, the patient is asymptomatic and illness free.

Discussion

Molar pregnancy, either partial or entire, is predicted to occur around 1 in 500 to One in 1000 pregnancies [1]. Cervical pregnancy has no known cause, Local cervical pathology, the majority of which is iatrogenic in nature, Asherman's Syndrome, like past dilatation & curettage, former C - section, prior cervical or uterine operations, & in vitro fertilization–embryo transfer, are likely to be the cause [5,6]. Excessive vaginal bleeding can be dangerous; fortunately, early detection and good treatment measures reduce fatality rates dramatically. There have been no recent cervical pregnancy-related deaths reported. [30] Ectopic cervical molar pregnancy is a very uncommon disorder, with an approximate occurrence of 1.5 per 1000,000 births [2]. According to a review, just five cases have been described. In women aged 35 and 25, D&C and D&C with compression have been used to treat two occurrences of cervical ectopic partial mole. [7,8] The first patient, who was 36 years old, had a cervical ectopic entire mole in three occurrences. She was evaluated & diagnosed two weeks after her evacuation and was given methotrexate, evacuation, and bimanual compression before receiving methotrexate-based treatment. [9] The next patient was a 28-year-old woman. She was diagnosed two months after a missed abortion was evacuated and treated with exfoliation and conservative surgery [4]. The third patient was 53 years old and underwent total hysterectomy since she was hemodynamically unstable and had a low hemoglobin level when she presented. [10] (Table1).

|

Reference |

Age |

Clinical presentation |

Histology |

Management |

Follow up |

|

7 |

35 |

Vaginal bleeding |

Partial mole |

Curettage |

BHCG 5IU/L |

|

6 weeks later |

|||||

|

9 |

36 |

Vaginal bleeding |

Complete mole |

Methotrexate , curettage and bimanual compression , followed by methotrexate |

BHCG <2 IU/L |

|

2 weeks post curettage |

14 weeks later |

||||

|

8 |

25 |

Vaginal bleeding |

Partial mole |

Curettage and bimanual compression |

BHCG <5IU/L |

|

3 weeks later |

|||||

|

4 |

28 |

Vaginal bleeding |

Complete mole |

Exfoliation and conservative surgery |

BHCG undetectable |

|

8 weeks post abortion |

12 weeks later |

||||

|

10 |

53 |

Heavy vaginal bleeding |

Complete mole |

Hysterectomy |

BHCG < 5IU/L |

|

5 weeks later |

|||||

|

Our case |

48 |

Heavy vaginal bleeding |

Partial invasive mole |

Hysterectomy |

BHCG < 5IU/L |

|

5 weeks later |

Fortunately, none of the five documented cases of cervical ectopic pregnancy resulted in maternal mortality [57], which matched our patient's outcome, who was in complete remission and did not require any further therapy. Until recently, the majority of cervical pregnancy patients (56) had their uterus removed due to uncontrollable hemorrhage from the aberrant implantation site. If a cervical ectopic pregnancy is detected early in pregnancy by ultrasonography, conservative therapy may be utilized. In a few case studies involving only one to 3 individuals, a variety of conservative approaches for the termination of cervical pregnancy have been described. [58, 59]

A review of the literature indicated that 25 of the 31 individuals with cervical pregnancy had previously undergone curettage. In another study, 18 of 19 patients had previously been curettage. [34] Vaginal bleeding is the most common symptom, which is typically without symptoms but can be accompanied by abdominal pain and urinary problems, especially in later pregnancies. [35] The cervix may be large, globular, or distended upon admission, and external os dilatation is common. [36, 37]

Accurate, early diagnosis is essential for successful conservative treatments. The incidence of the intracervical ectopic gestational sac or trophoblastic mass within the cervix is used to rule out the possibility of spontaneous abortion-in-progress. These two entities are easily distinct in most situations. The gestational sac is generally spherical or oval in cervical pregnancy, and it might include a yolk sac and/or a baby with a heartbeat. The sac is often crenated in a spontaneously aborting pregnancy, there is no foetal heart activity, and it decreases or evaporates within a few days. If heart activity is detected, cervical ectopic pregnancy can be verified, and it is strongly suspected if the gestational sac is well formed, especially if it has a yolk sac. A follow-up ultrasound 1-2 days after the initial can only be used to confirm the diagnosis in a few cases. Transvaginal ultrasonography improves visibility in situations of early cervical pregnancy. The gestational sac, as well as the endometrium and adnexa, can all be examined. It is limited, however, due to the scanning technique's limited field of vision. While weak in imaging detail, transabdominal imaging offers for a single-plane image of the uterus, vagina and canal. It might be desirable in advanced cases of cervical pregnancy. Ushakov proposed it in a review of the literature. [37] Intracervical placentation is defined as an uninterrupted segment of the cervical canal seen between endometrium and the gestational sac. A true cervical pregnancy must be distinguished from an isthmicocervical pregnancy, that necessitates the presence of a closed internal os. The internal os is thought to be at the level of the uterine arteries' insertion in a coronal view. The sac will be situated beneath the uterine artery insertion, that will be apparent if the internal os cannot be seen. The period of pregnancy affects the ultrasonography differential diagnosis of cervical pregnancy. Before 1980, a cervical pregnancy was identified when unexpected bleeding occurred following dilation and curettage for a suspected incomplete abortion. [60] However, a first trimester ultrasound examination can now quickly diagnose it. Methotrexate, either with or without intra-amniotic potassium chloride, has made significant progress in terminating cervical ectopic pregnancy, particularly when foetal heart is detected. [61]

Early cervical pregnancy can be confused with the cervical phase of miscarriages, which is characterized as a "spontaneous abortion of an intrauterine pregnancy into the cervical canal when the abortus is trapped by a refractory external os, causing the cervical canal to balloon out. Differentiating the latter from a cervical pregnancy may be aided by a variety of observations. In cervical pregnancy, the larger or globular uterus is more helpful than the hourglass type.

The ‘sliding sign,' which typically arises when an abortus' gestational sac slides against by the endocervical canal with light pressure by the sonographer & is not detected in the implanted cervical pregnancy & similarly was discovered by Jurkovic on transvaginal scanning, also may help to differentiate. In cervical pregnancy, local endocervical tissue invasion by the trophoblast is also common, and ultrasonography might be able to locate the area. [38] Proliferating chorionic villi can penetrate deep inside the fibromuscular layer because the cervical mucosa provides minimal protection against trophoblast invasion. In the invasive zone, the hyperechoic trophoblastic ring will be broader. The remaining eroding cervical wall may be more difficult to discern. Peritrophoblastic arterial flow, or low resistance placental blood flow due to trophoblastic villi, has been demonstrated to help with tubal ectopic pregnancy detection using colour flow. Doppler [39, 40] will be useful in both therapy as well as diagnosis monitoring in cervical pregnancy. [41] In an intracervical position, the low resistance flow can be identified, indicating the implantation site. According to Jurkovic, a non-viable sac entering through into the cervix would not have had peritrophoblastic flow. Benson & Doubilet, on other hand, questioned Color Doppler, declaring that the overlap of data between miscarriage & cervical ectopic pregnancy was too great to provide useful clinical information. [42] If a viable fetus is detected later, mistaken the sac position for that of an intrauterine sac with inadequate placentation could be a diagnostic stumbling point. The presence of a vacant or unoccupied endometrial cavity should imply that the analysis is correct. Because of the favorable settings, if a cervical tumor is discovered late and without viable products, the margins may be irregular or ill-defined due to trophoblastic invasion, which is less common with cervical pregnancy. Miscarriage, either total or inevitable, degenerative leiomyomata, gestational trophoblastic disease, and cervical cancer are all possibilities at this point. The spherical shape, empty or tiny uterus, closed endometrial canal, internal os, closed endometrial canal, are all indicators that the diagnosis is correct. To avoid hysterectomy & preserve fertility, prudent pharmacological and/or surgical treatment is frequently employed after the diagnosis.

There are five different types of CP treatment options:

- Foley catheter tamponade or local prostaglandin injection [45]: The usage of a Foley catheter, gently inserted past the external os, followed by 30 mL saline bulb inflation, has been employed largely when other procedures (for example; curettage) have resulted in hemorrhage. Tamponade with packing is ineffective. [20, 44] Few writers have mentioned the use of prostaglandins in cervical pregnancy. In a 9-week cervical pregnancy, Dall used it both systemically and intra-amniotically, but intractable bleeding forced an emergency hysterectomy despite simultaneous curettage. [68] Spitzer then published three cases of cervical pregnancy in the first trimester that were effectively cured with curettage & local prostaglandin administration (12.5 to 25 g of sulprostone).[69]

- Cervical cerclage, uterine artery ligation, vaginal ligation of cervical arteries, internal iliac artery ligation, & angiographic embolization of the cervical, uterine, or internal iliac arteries are all options for reducing blood flow. This is commonly done before to surgical treatment, such as curettage, or in combination with chemotherapy as a conservative therapy option intended at preserving future fertility. When traditional conservative treatments, such as chemotherapy, fail to halt the bleeding, embolization is used as a "rescue" treatment. [43,46]

- Removal of trophoblast tissue by surgery: Curettage and hysterectomy are the two most common ways for removing trophoblast tissue surgically. [37] Curettage is an age-old strategy of protecting fertility, however it carries the danger of bleeding. As a result, it's been used with mechanical techniques including cervical artery ligation and tamponade. Intractable hemorrhage, 2nd trimester or 3rd trimester identification of CP, and perhaps to prevent blood transfusion & emergency surgery in a woman not eager of fertility, primary hysterectomy may still be the recommended therapeutic option. According to a study, 100 percent of CP after 12 weeks of pregnancy underwent hysterectomy. Hysterectomy is 40 percent more likely after dilation and curettage alone. In most cases, attempts to digitally or instrumentally remove the uterus result in serious hemorrhage, necessitating surgery. If tamponade is the primary method of hemostasis, significant subsequent bleeding requiring hysterectomy might happen up to 6 weeks later. Along the formation of collateral circulation afterward uterine artery embolization, the outcome is substantially better when used in conjunction with further medical or surgical processes to limit loss of blood and stop remaining gestational tissue from active regeneration.[70]

- Intra-amniotic feticide: An ultrasound-guided intra-amniotic instillation of KCL potassium chloride and/or methotrexate has been utilized to treat CP.

- Treatment with methotrexate for the preservation of the uterus in individuals with whichever viable or nonviable CP (91 percent). [48] Although intra amniotic potassium chloride instillation in the presence of heart activity has been advised, the treatment necessitates an increased level of competence and is accompanying with the hazard of hemorrhage. [19]

Methotrexate is a chemotherapeutic drug that can stop trophoblasts from growing by stopping DNA production and cell division. It is, however, not recommended in the presence of active renal or hepatic illness, as well as leukopenia or thrombocytopenia. Systemic methotrexate dosage regimens differed significantly. On days 4 and 7, blood hCG levels were monitored after a single dosage (50 mg/m2 intramuscularly [IM]). If there is a 15% or larger variance in serum hCG levels, the check is repeated weekly until the difference is unnoticeable. The methotrexate dose should be repeated if the difference becomes less than 15%, and day 1 should be restarted. Multiple-dose regimens (1 mg/kg on days 1, 3, 5, 7, & 9 IM) with or without 0.1 mg/kg of folinic acid rescue (leucovorin) on alternate days could also be used. There should be no more than 5 doses of methotrexate given in a row with a one-week interval between them Song proposed an alternate high-dose methotrexate regimen in 2009, [71] consisting of a single course of 100 mg/m2 plus a dosage of 200 mg/m2 intravenous injection in 500 mL of normal saline solution with a 0.1 mg/kg of folinic acid rescue. [61] Methotrexate, at a dose of 50 mg/m2, can also be used intra-amniotically or intracervically However, active bleeding following local injection is a distinct possibility due to rupture of the intra-amniotic membrane. Unluckily, there is currently insufficient and inconsistent evidence to compare the effectiveness of various treatments. Cervical pregnancy resolved between 2 and 12 weeks after treatment, as calculated by serum hCG levels as well as sonographic appearance of the cervix. A potential issue of treatment with methotrexate is the inability to forecast the possibility of significant bleeding from the uninvoluted & atonic cervix after trophoblast shedding.

Methotrexate is the most often used agent, which can be given as a single dose or in several doses, with or without folinic acid. Although methotrexate has been given intramuscularly, intravenously, intra-cervically, and intra-amniotically [36] it has been linked to bone marrow suppression, gastrointestinal problems, and an increase in hepatic transaminases. A combination of laparoscopy assisted uterine artery closure followed by hysteroscopy local endocervical excision to eradicate Cervical Pregnancy has recently been described as a fertility-preserving alternative treatment. [19, 48]

A local injection of potassium chloride (KCl) (3–5 mL at 2 mEq/mL) under transvaginal ultrasound monitoring can be used as an alternative to methotrexate treatment. When administered as a primary therapy, in combination with systemic chemotherapy, or following a failed systemic methotrexate treatment, this strategy has a 90 percent success rate. [72] As a result, in the treatment of heterotopic cervical pregnancy, KCl injection could be a viable alternative to local or systemic chemotherapy. Though, there is still a chance of major bleeding or infection at the location of implantation, necessitating additional treatment.

Higher chances of treatment failure have been linked to the existence of a viable foetus or advanced gestational age. [51] According to Kung, 12 of the 18 cases that were successfully treated with methotrexate required adjuvant treatment. [49] The intramuscular method is frequently favoured among the numerous methotrexate administration techniques. The patient must be hemodynamically stable and follow all post-treatment instructions. [9] As seen in our second example, a decrease in weekly serum beta hCG levels after therapy indicates an effective therapeutic intervention. [61]

Yitzhak advised a progressive conservative approach to treating cervical ectopic pregnancy, starting with intramuscular methotrexate and then going to intra-arterial methotrexate if that failed. [50] They propose subsequent intervention with intra-arterial embolization if there is an escalation in bleeding or a relapse of vaginal hemorrhage while on methotrexate. This method is used by Leeman and Wendland in their recommended therapeutic algorithm. [36] They provide intra-amniotic potassium chloride in addition to systemic methotrexate if the gestation is greater than 9 weeks or less than 9 weeks if a fetal heart beat is detected. Arterial embolization has been used to minimise bleeding and facilitate the continuation of a simultaneous intrauterine heterotopic pregnancy in the context of a cervical pregnancy. [48] When a pregnancy is discovered in the second or third trimester, a hysterectomy may be required. A hemorrhaging patient's options for treatment include tamponade with a major vascular ligation, foley balloon, or angiographic embolization with hysterectomy, which is kept for intractable bleeding. When it comes to terminating a Cervical pregnancy, it's normal to explore multiple approaches. [19]

When the patient's hCG level was 12,300 mIU/mL three weeks following admission, a transvaginal examination revealed a cervical cystic lesion with a solid component of about 4 cm in diameter. In a recent paper [36], Leeman and Wendland mention the persistence of a sac despite clinical clearance, & Brown found that persistent sonographic abnormalities were common in ectopic pregnancies treated with methotrexate in his publication. Women who are treated with methotrexate for gestational trophoblastic illness have not been reported to have teratogenic consequences; however, these women are recommended to forgo conception for 6-12 months. [52, 53] It's also a good idea to wait at least 6 months before getting pregnant if you had a cervical pregnancy to lessen the risk of difficulties. Premature labor or an incompetent cervix, which are caused by predisposing factors rather than the cervical pregnancy itself, must also be watched for. According to Ushakov's analysis of reproductive function following cervical pregnancy, 34 pregnancies in 29 women were documented after conservative cervical pregnancy care between 1911 & 1996. Twelve of the pregnancies took place before 1990. [37] Spitzer reported term births in patients who had a prior cervical pregnancy and were cured with curettage and prostaglandin injection. [45] The authors of a retrospective study that looked at the total efficacy of methotrexate treatment for cervical pregnancy found no evidence that the patients' reproductive performance was impacted. [54] (Table 1)

|

Reference |

Age |

Clinical presentation |

Histology |

Management |

Follow up |

|

7 |

35 |

Vaginal bleeding |

Partial mole |

Curettage |

BHCG 5IU/L |

|

6 weeks later |

|||||

|

9 |

36 |

Vaginal bleeding |

Complete mole |

Methotrexate , curettage and bimanual compression , followed by methotrexate |

BHCG <2 IU/L |

|

2 weeks post curettage |

14 weeks later |

||||

|

8 |

25 |

Vaginal bleeding |

Partial mole |

Curettage and bimanual compression |

BHCG <5IU/L |

|

3 weeks later |

|||||

|

4 |

28 |

Vaginal bleeding |

Complete mole |

Exfoliation and conservative surgery |

BHCG undetectable |

|

8 weeks post abortion |

12 weeks later |

||||

|

10 |

53 |

Heavy vaginal bleeding |

Complete mole |

Hysterectomy |

BHCG < 5IU/L |

|

5 weeks later |

|||||

|

Our case |

48 |

Heavy vaginal bleeding |

Partial invasive mole |

Hysterectomy |

BHCG < 5IU/L |

|

5 weeks later |

Table 1: Description of all of the reported cases of cervical ectopic pregnancies in the literature.

Conclusion

In the realm of early pregnancy, cervical ectopic pregnancy remains a key concern. We described the numerous diagnostic approaches and assessed the efficacy of various treatment options in this study. Finally, the current gold standard for diagnosis is high-resolution transvaginal sonography or magnetic resonance imaging with histological evaluation of the conception products. Cervical pregnancy screening using ultrasound and conservative treatment regimens takes reduced linked morbidity & increased the risk of long-term fertility in those who have been compromised. A ten-year retrospective study of 1800 ectopic pregnancies was conducted. Cervical pregnancy is rare, however it is becoming increasingly common as a result of risk factors like a high caesarean section rate and increased use of assisted reproductive technology to address infertility.

Primary medical therapy for early cervical pregnancy provides a enhanced prognosis than surgery in more than 91 percent of the cases, and can obviate the need for hysterectomy. According to a recent literature review, the medical group had an 11 percent chance of substantial bleeding and a 3% chance of hysterectomy, while the surgical group had a 35 percent chance of hemorrhage & a 15% chance of hysterectomy. Patients having cervical pregnancies identified throughout the 2nd trimester, with unbalanced vital signs & severe vaginal hemorrhage, with accompanying uterine pathology, who are Jehovah's witnesses, & those who had completed their families should then consider total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH). However, due to the expanded barrel-shaped cervix, there will still be an elevated threat of urinary tract damage. Women should, however, be fully informed about the procedure's hazards as well as the difficulty of predicting post-treatment consequences. Treatment is influenced by the kind of intramural pregnancy, gestational age, and severity of symptoms at presentation. The success of conservative treatment is dependent on early ultrasound detection, which can lower the risk of serious life-threatening conditions like as bleeding, which may necessitate hysterectomy or blood transfusion. The advantages of early therapy substantially outnumber the hazards. Cervical ectopic molar pregnancy can produce severe vaginal bleeding in a female in her fifth decade, therefore doctors should be aware of this. According to a recent literature analysis, 49 percent of viable cervical pregnancies required a second operational treatment to remove the abnormal trophoblastic cells. The existence of blood hCG levels of 10,000 mIU/mL or above, gestational age of 9 weeks or far ahead, foetal heartbeat, or foetal crown-rump length of greater than 10 mm are all prognostic indicators for an substandard first methotrexate management of cervical pregnancy. The patient's ultrasound and vaginal speculum exam report revealed a ruptured cystic lesion with elevated BHCG, which resolved following the procedure without the use of methotrexate. D and C was performed. Histology confirmed the presence of an ectopic cervical invasive mole, and a hysterectomy was performed. Four months after hysterectomy, the patient is asymptomatic and disease-free.

Conflict of Interest: I disclose no conflicts of interest

References

- Sebire NJ, Lindsay I, Fisher RA, Savage P, Seckl MJ (2005). Overdiagnosis of complete and partial hydatidiform mole in tubal ectopic pregnancies. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 24: 260-264

- Gillespie AM, Lidbury EA, Tidy JA, Hancock BW (2004). The clinical presentation, treatment and outcome of patients diagnosed with possible ectopic molar gestation. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 14: 366-369

- Cepni I, Murray H, Baakdah H, Bardell T, Tulandi T (2005). Diagnosis and treatment of ectopic pregnancy. CMAJ. 173: 90

- Schwentner L, Schmitt W, Bartusek G, Kreienberg R, Herr D (2011). Cervical hydatidiform mole pregnancy after missed abortion presenting with severe vaginal bleeding. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 156: 9-11

- Yankowitz J, Leak J, Huggins G, Gazaway P, Gates E (1994). Cervical pregnancy case reports and current literature review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 49: 49-54

- Dicker D, Feldberg D, Samuel N, Goldman JA (1985). Etiology of cervical pregnancy: association with abortion, pelvic pathology, IUDs and Asherman’s syndrome. J Reprod Med. 30: 25-27

- Chapman K (2001). Cervical pregnancy with hydatidiform mole. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 80: 657-658

- Aytan H, Caliskan AC, Demirturk F, Koseoglu RD (2008). Cervical partial hydatidiform molar pregnancy. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 66: 142-144

- Wee HY, Tay EH, Soong Y, Loh SF (2003). Cervical hydatidiform molar pregnancy. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol. 43: 473-474

- Desdicioglu R, Yigit S, Ocal I, Ekinci N, Civas E, Yilmaz B (2014). Spontaneous rupture of cervical hydatidiform molar pregnancy in a 53-year-old woman. J Cases Obstet Gynecol. 1:64-67

- Salem S (1977). Ultrasound diagnosis of trophoblastic disease. Ultrasonography in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 255-266.

- Vassilakos P, Riotton G, Kajii T (1977). Hydatidiform mole: two entities. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 127: 167-170

- Kajii T, Ohama K (1977). Androgenetic origin of hydatidiform mole. Nature. 268: 633-634

- Yamashita K, Wake N, Araki T, Ichinoe R, Makoto K (1979). Human lymphocyte antigen expression in hydatidiform mole. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 135: 597-600

- Azuma C, Saji F, Tokugawa Y, Kimura T, Nobunagaet T et al. (1991). Application of gene amplification to analysis of molar mitochondrial DNA. Gynecol Oncol. 40: 29-33

- Szulman AE, Surti U (1978). The syndromes of hydatidiform mole. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 132: 20-27

- Jones HW, Cobton AC, Brunett LS (1988). Novak’s Textbook of Gynecology. Williams & Wilkins. 499

- Berkowitz RS, Goldstein DP, Bernstein MR (1985). Natural history of partial molar pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 66: 677-681

- Szulman AE, Surti U (1982). The clinicopathological profile of the partial hydatidiform mole. Obstet Gynecol. 59: 597-602

- Leeman LM, Wendland CL (2000). Cervical ectopic pregnancy: diagnosis and treatment. Arch Fam Med. 9: 727

- Cepni I, Ocal P, Erkan S, Erzik B (2004). Conservative treatment of cervical ectopic pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 81: 1130-1132

- Kumar S, Vimalam N, Dadhwal V, Mittal S (2004). Heterotopic cervical and intrauterine pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 112: 217-220

- Weyerman PC, Verhoeven AT, Alberda AT (1989). Cervical pregnancy after IVF. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 161: 1145-1146

- Raskin MM (1978). Diagnosis of cervical pregnancy by ultrasound. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 130: 234-235

- Baskin MM (1978). Diagnosis of cervical pregnancy by ultrasound. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 130: 234-235

- Sherer DM, Abramowicz JS, Thompson HO, Liberto L, Angel C, et al. (1991). Diagnosis of cervical pregnancy by sonography. J Ultrasound Med. 10: 409-411

- Roussis P, Ball RH, Fleischen AC, Herbert CM (1992). Cervical pregnancy: a case report. J Reprod Med. 37: 479-481

- Meyerovitz MF, Lobel SM, Harnington DP, Bengston JM (1991). Preoperative uterine artery embolization in cervical pregnancy. JVIR. 2: 95-97

- Fowler DJ, Lindsay I, Seckl MJ (2006). Routine pre-evacuation ultrasound diagnosis of hydatidiform mole. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 27: 56-60

- Murray H, Baakdah H, Bardell T, Tulandi T (2005). Diagnosis and treatment of ectopic pregnancy. CMAJ. 173: 905

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1995). Ectopic pregnancy—United States, 1990–1992. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 44: 46

- Altieri A, Franceschi S, Ferlay J, Smith J, La Vecchia C (2003). Epidemiology and aetiology of gestational trophoblastic diseases. Lancet Oncol. 4: 670-678

- Garner EL, Goldstein DP, Feltmate CM, Berkowitz RS (2007). Gestational trophoblastic disease. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 50: 22-112

- Shinagawa S, Nugayama M (1969). Cervical pregnancy as a possible sequela of induced abortion. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 105: 282-284

- Copas P, Semmer J (1983). Cervical ectopic pregnancy at 28 weeks. J Clin Ultrasound. 11: 328-330

- Leeman LM, Wendland CL (2000). Cervical ectopic pregnancy: diagnosis with endovaginal ultrasound. Arch Fam Med. 9: 72-77

- Ushakov FB, Elchalal V, Aceman PJ, Schenker JK (1997). Cervical pregnancy: past and future. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 52: 45-59

- Jurkovic D, Hacket E, Campbell S (1996). Diagnosis and treatment of early cervical pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 8: 373-380

- Pellerito JS, Taylor KJW, Quedens-Case C, Hammers LW, Scouttet LM, et al. (1992). Ectopic pregnancy: evaluation with color flow imaging. Radiology. 183: 407-411

- Emerson DS, Cartier MS, Altieri LA, Felker RE, Smith WC, et al. (1992). Diagnostic efficiency of color Doppler in ectopic pregnancy. Radiology. 183: 413-420

- Benson CB, Doubilet PM. (1996). Strategies for conservative treatment of cervical ectopic pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 8: 371-372

- Timor-Tritsch IE, Monteagudo A, Mandeville EO, Peisner DB, Anaya GP, et al. (1994). Successful management of viable pregnancy by local injection of methotrexate guided by transvaginal ultrasonography. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 170: 737-739

- Bachus KE, Stone D, Bosun MD, Thickman D. (1990). Conservative management of cervical pregnancy with subsequent fertility. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 162: 450-451

- Spitzer D, Steiner M, Graf A, Zajc M, Staudach A. (1997). Conservative treatment of cervical pregnancy by curettage and local prostaglandin injection. Hum Reprod. 12: 860-866

- Nappi C, D’Elia A, DiCarlo C, Giordano E, DePlacido G, et al. (1999). Conservative treatment by angiographic uterine artery embolization of a 12 week cervical ectopic pregnancy. Hum Reprod. 14: 1118-1121

- Cosin JA, Bean M, Grow D, Wiczyk H. (1997). The use of methotrexate and arterial embolisation in a case of cervical pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 67: 1169-1171

- Honey L, Leader A, Claman P. (1999). Uterine artery embolization—a successful treatment to control bleeding cervical pregnancy with a simultaneous intrauterine gestation. Hum Reprod. 14: 553-555

- Kung FT, Chang JC, Tsai YC. (1997). Subsequent reproduction and obstetric outcome after methotrexate treatment of cervical pregnancy: a review of original literature and international collaborative followup. Hum Reprod. 12: 591-595

- Yitzhak M, Orvieto R, Nitke S, Neuman-Levin M, Ben-Rafael Z, et al. (1999). Cervical pregnancy-a conservative stepwise approach. Hum Reprod. 14: 847-849

- Barham JM, Paine M. (1989). Reproductive performance after a cervical pregnancy: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 44: 650-655

- Brown DL, Felker RE, Stovall TG, Emerson DS, Ling FW. (1991). Serial endovaginal sonography of ectopic pregnancies treated with methotrexate. Obstet Gynecol. 77: 406-409

- Walden PA, Bagshawe KD. (1976). Reproductive performance of women successfully treated for gestational trophoblastic tumours. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 125: 1108-1114

- Kung FT, Chang SY. (1999). Efficacy of methotrexate treatment in viable and nonviable cervical pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 181: 1438-1444

- Shih IE, Kurman RJ. (2002). Molecular basis of gestational trophoblastic disease. Curr Mol Med. 2: 1-12

- Parente JT, Chau-Su O, Levy J, Legatt E. (1983). Cervical pregnancy analysis: a review and report of five cases. Obstet Gynecol. 62: 79-82

- Sherer DM, Abramowicz JS, Thompson HO, Liberto L, Angel C, et al. (1991). Comparison of transabdominal and endovaginal sonographic approaches in the diagnosis of a case of cervical pregnancy successfully treated with methotrexate. J Ultrasound Med. 10: 409-411

- Roussis P, Ball RH, Fleischen AC, Herbert CM. (1992). Cervical pregnancy: a case report. J Reprod Med. 37: 479-481

- Meyerovitz MF, Lobel SM, Harnington DP, Bengston JM. (1991). Preoperative uterine artery embolization in cervical pregnancy. JVIR. 2: 95-97

- Leeman LM, Wendland CL. (2000). Cervical ectopic pregnancy. Diagnosis with endovaginal ultrasound examination and successful treatment with methotrexate. Arch Fam Med. 9: 72-77

- Polak G, Stachowicz N, Morawska D, Kotarski J. (2011). Treatment of cervical pregnancy with systemic methotrexate and KCl solution injection into the gestational sac: case report and review of literature. Ginekol Pol. 82: 386-389

- Wells M. (2007). The pathology of gestational trophoblastic disease: recent advances. Pathology. 39: 88-96

- Green CL, Angtuaco TL, Shah HR, Parmley TH. (1996). Gestational trophoblastic disease: a spectrum of radiologic diagnosis. Radiographics. 16: 1371-1384

- Ober WB, Fass RO. (1961). The early history of choriocarcinoma. Ann NY Acad Sci. 172: 299-426

- Mueller UW, Hawes CS, Wright AE, Petropoulos A, DeBoni E, et al. (1990). Isolation of fetal trophoblast cells from peripheral blood of pregnant women. Lancet. 336: 197-200

- Sebire NJ, Fisher RA, Rees HC. (2003). Histopathological diagnosis of partial and complete hydatidiform mole in the first trimester of pregnancy.

- Hou JL, Wan XR, Xiang Y, Qi QW, Yang XY. (2008). Changes of clinical features in hydatidiform mole: analysis of 113 cases. J Reprod Med. 53: 629-633

- Berkowitz RS, Goldstein DP, Bernstein MR. (1985). Natural history of partial molar pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 66: 677-681

- Dall P, Pfisterer J, Du Bois A, Wilhelm C, Pfleiderer A. (1994). Therapeutic strategies in cervical pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 56: 195-200

- Spitzer D, Steiner H, Graf A, Zajc M, Staudach A. (1997). Conservative treatment of cervical pregnancy by curettage and local prostaglandin injection. Hum Reprod. 12: 860-866

- Jurkovic D, Hacket E, Campbell S. (1996). Diagnosis and treatment of early cervical pregnancy: a review and a report of two cases treated conservatively. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 8: 373-380

- Song MJ, Moon MH, Kim JA, Kim TA. (2009). Serial transvaginal sonographic findings of cervical ectopic pregnancy treated with high-dose methotrexate. J Ultrasound Med. 28: 55-61

- Hung TH, Jeng CJ, Yang YC, Wang KG, Lan CC. (1996). Treatment of cervical pregnancy with methotrexate. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 53: 243-247

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.