Caylah Manuel, Lauren H Sutton, Katherine Aymond, Tyanna A. Robinson, Helen Calmes*

by University Medical Center New Orleans, Department of Pharmacy, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA

*Corresponding author: Helen Calmes, University Medical Center New Orleans, Department of Pharmacy, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA.

Received Date: 09 December, 2025

Accepted Date: 16 December, 2025

Published Date: 19 December, 2025

Citation: Manuel C, Sutton LH, Aymond K, Robinson TA, Calmes H (2025) Safety of Alteplase Versus Tenecteplase for Acute Ischemic Stroke. Int J Cerebrovasc Dis Stroke 8: 203. https://doi.org/10.29011/2688-8734.100203

Abstract

Purpose: The 2019 American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke (AIS) recommend intravenous (IV) thrombolytic therapy for AIS patients presenting within 4.5 hours of symptom onset. Alteplase was historically the thrombolytic of choice for this indication. However, tenecteplase was recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for AIS. This study compared the safety of each agent in patients with AIS. Methods: A single-center, retrospective, cohort study included patients from June 30, 2022, through June 30, 2024. Adults who received IV tenecteplase or alteplase for AIS were included. The primary objective was major bleeding within 24 hours of thrombolytic administration. Results: Forty-two patients received tenecteplase, and 29 received alteplase for AIS (N = 71). There was an increase in atrial fibrillation [n = 5 (12%) vs. n = 0 (0%), P = 0.074], a higher initial NIHSS [8 (5-12) vs. 5 (3-8), P = 0.04], and a higher thrombectomy rate [n = 13 (31%) vs. n = 5 (17.2%), P = 0.192] in the tenecteplase group. The primary outcome occurred in six patients receiving tenecteplase and one patient receiving alteplase (14% vs. 3%, P = 0.228). There were 10 bleeding events during admission [n = 8 (19%) vs. n = 2 (7%), P = 0.511]. There were no differences in length of stay, mortality, or hypersensitivity reactions. Conclusion: No difference in the incidence of major bleeding or other adverse events was observed between patients receiving tenecteplase and those receiving alteplase for AIS.

Keywords: tenecteplase, alteplase, acute ischemic stroke, thrombolytic, intracranial hemorrhage

Introduction

Acute ischemic stroke (AIS) is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States [1]. The 2019 American Heart Association (AHA)/American Stroke Association (ASA) Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients with AIS recommend intravenous (IV) thrombolytic therapy for patients presenting within 4.5 hours of symptom onset [2]. Thrombolysis serves to prevent further cerebral ischemic damage and restore intracranial blood flow to the affected area [3]. While alteplase has been the historic standard of care, these guidelines also state that tenecteplase may be considered in select patient groups [2].

Tenecteplase, a thrombolytic approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration for ST-elevation myocardial infarction and AIS (as of March 4, 2025), offers several advantages over alteplase, including IV push administration and potential cost savings [4]. Additionally, due to genetic modification of tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA), tenecteplase has a 15-fold higher fibrin specificity and a 6-fold prolonged plasma half-life compared to alteplase [5]. This theoretically leads to more effective thrombus targeting. Tenecteplase also exhibits increased resistance to plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1) [5]. The increase in PAI-1 resistance allows the thrombolytic effect to be achieved with a lower dose of medication. Coupled with higher fibrin specificity, these attributes of the drug may lead to a lower risk of bleeding complications following administration [5].

Bleeding complications, such as intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), including hemorrhagic conversion following AIS, may lead to significant morbidity or mortality. During AIS, there is an early disruption in the blood-brain barrier secondary to an increase in the enzyme matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) [6]. The increase in MMP-9 may allow blood to leak into brain tissue, causing hemorrhagic transformation [6]. Any patient with AIS is at risk for an ICH; however, the timeframe for this risk may vary depending on the interventions received. In patients who receive a thrombolytic, hemorrhagic conversion is often noted within the first 24 hours, with a decreasing risk after 36 hours [6]. If the patient undergoes a mechanical thrombectomy, there is a higher risk of hemorrhagic transformation within the first 24 hours [6].

There is evidence to suggest that tenecteplase may be as safe and efficacious as alteplase. The ATTEST trial, published in 2015, examined penumbral salvage in adult patients with supratentorial AIS receiving alteplase or tenecteplase 0.25 milligrams per kilogram (mg/kg) and identified no difference in penumbral salvage or serious adverse events [7]. NOR-TEST then analyzed thrombolytic-eligible adults who received alteplase or tenecteplase 0.4 mg/kg for functional outcomes (Modified Rankin Scale; mRS) at 3 months and showed no difference in efficacy with a similar safety profile, even at a higher tenecteplase dose [8]. EXTENDIA TNK narrowed the population to include only thrombectomyeligible adults with AIS secondary to a large vessel occlusion [9]. Tenecteplase 0.25 mg/kg was superior to alteplase for the primary outcome of reperfusion of >50% of involved ischemic territory or absence of retrievable thrombus at time of initial angiographic assessment (22% vs. 10%, 95% CI 1.1 to 4.4) [9]. Additionally, patients who received tenecteplase had significantly better 90day functional outcomes without an increased risk of bleeding [9]. The largest trial to date, the AcT trial, included 1,600 adult patients and found that tenecteplase was non-inferior to alteplase for the primary outcome of mRS of 0–1 at 90–120 days (36.9% vs. 34.8%, 95% CI -2.6 to 6.9) [10]. Additionally, no difference in symptomatic ICH or 90-day mortality was noted [10].

Based on the previous literature, the preferred thrombolytic agent for AIS at the trial site, an academic medical center and nationally certified Primary Stroke Center, transitioned from alteplase to tenecteplase in July 2023. The purpose of this study was to examine the safety of tenecteplase compared to alteplase in patients with AIS.

Methods

This Institutional Review Board-approved, single-center, retrospective cohort study reviewed patients admitted between June 30, 2022, and June 30, 2024. Patients were identified via an electronic medical record query and manual chart review. Eligible patients were those who were at least 18 years old and who received tenecteplase or alteplase for AIS. Patients were excluded if they were incarcerated pregnant or if they received the thrombolytic for an indication other than AIS. For AIS, tenecteplase was dosed at 0.25 mg/kg (maximum 25 mg) and alteplase was dosed at 0.9 mg/ kg (maximum 90 mg).

The primary outcome of this study was the incidence of major bleeding within 24 hours of receiving a thrombolytic. Major bleeding was defined as a new ICH on follow-up imaging or the need for blood transfusion due to an acute decrease in hemoglobin of at least 2 g/dL. Secondary outcomes included any bleeding event during admission, hypersensitivity reactions, angioedema, intensive care unit (ICU) length of stay, and in hospital-mortality. Baseline characteristics collected for each patient included age, weight, height, body mass index (BMI), gender, race, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) at admission, Modified Rankin Scale (mRS) at admission, blood glucose at admission, international normalized ratio (INR), and home medications of interest.

Data was analyzed using descriptive statistics for demographic data, and the primary outcome was analyzed using Fisher’s exact test. Other nominal data were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test or chi-square test, as appropriate. Continuous data were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM® SPSS® Statistics for Windows (version 28.0, Armonk, NY).

Results

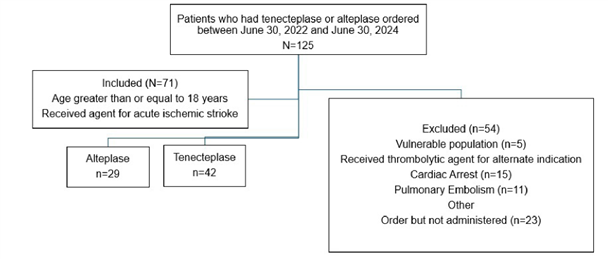

An initial patient list generated from the electronic medical record identified 125 thrombolytic administrations within the study period. After screening for inclusion and exclusion criteria, there were 71 eligible patients (Figure 1). Of the patients included, 42 patients (59%) received tenecteplase and 29 patients (41%) received alteplase.

Figure 1: Flow chart showing final cohort assignments for patients based on inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Baseline characteristics were compared between patients receiving tenecteplase and alteplase (Table 1). There was a significant difference noted when comparing baseline NIHSS (8 vs. 5, P = 0.04). All other characteristics were non-significant. When assessing past medical history, five patients in the tenecteplase group had a history of atrial fibrillation compared to zero patients in the alteplase group (12% vs. 0%, P = 0.074). Likewise, more patients in the tenecteplase group had a past medical history of stroke [n = 15 (35.7%) vs. n = 8 (27.6%), P = 0.472]. When assessing home medications, three patients in the tenecteplase group and one in the alteplase group were prescribed anticoagulation outpatient.

|

Tenecteplase (n=42) |

Alteplase (n=29 |

) |

P value |

|

|

Age, mean (SD), years |

59.0 (11.4) |

57.7 (14.8) |

0.683 |

|

|

Gender, No. (%), male |

23 (54.8) |

15 (51.7) |

0.660 |

|

|

Race, No. (%) |

||||

|

Black |

25 (59.5) |

22 (75.9) |

0.153 |

|

|

White |

10 (23.8) |

6 (20.7) |

0.757 |

|

|

Hispanic |

3 (7.1) |

1 (3.4) |

0.640 |

|

|

Asian |

2 (4.8) |

0 (0.0) |

0.510 |

|

|

Other |

2 (4.8) |

0 (0.0) |

0.510 |

|

|

Weight, median (IQR), kg |

82.9 (71.0-97.0) |

83.6 (72.0-109.7) |

0.494 |

|

|

Past Medical History, No. (%) |

||||

|

Atrial Fibrillation |

5 (12.0) |

0 (0.0) |

0.074 |

|

|

Hypertension |

29 (69.0) |

19 (65.5) |

0.755 |

|

|

CAD |

6 (14.3) |

3 (10.3) |

0.624 |

|

|

Stroke/ TIA |

15 (35.7) |

8 (27.6) |

0.472 |

|

|

Diabetes |

13 (31.0) |

10 (34.4) |

0.755 |

|

|

Smoking |

24 (57.0) |

17 (59.6) |

0.901 |

|

|

Home Medications, No. (%) |

||||

|

Aspirin Monotherapy |

8 (19.0) |

6 (20.7) |

0.867 |

|

|

P2Y12 Monotherapy |

3 (7.1) |

1 (3.4) |

0.514 |

|

|

DAPT |

4 (9.5) |

6 (20.7) |

0.189 |

|

|

Anticoagulant |

3 (7.1) |

1 (3.4) |

0.640 |

|

|

HMG-CoA Reductase Inhibitor |

16 (38.1) |

10 (34.4) |

0.756 |

|

|

Estrogen Based Contraception |

1 (2.4) |

0 (0.0) |

0.410 |

|

|

Thrombectomy performed, No. (%) |

13 (31.0) |

5 (17.2) |

0.192 |

|

|

NIHSS, median (IQR) |

8 (5-12) |

5 (3-8) |

0.040 |

|

|

Modified Rankin Scale, median (IQR) |

2 (0-3) |

1 (0-3) |

0.241 |

|

|

Time from LKN, median (IQR), hours |

1.6 (1.0-2.5) |

1.5 (1.0-2.5) |

0.358 |

|

|

INR, median (IQR) |

1.0 (0.9-1.0) |

1.0 (0.9-1.0) |

0.628 |

|

|

Blood Glucose, median (IQR), mg/dL |

126.0 (104.5-150.0) |

112.0 (92.0-155.0) |

0.196 |

|

|

Abbreviations: TIA, Transient Ischemic Attack; CAD, Coronary Artery Disease; HTN, Hypertension; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; LKN, Last Known Normal; INR, International Normalized Ratio; DAPT, Dual Antiplatelet Therapy |

||||

Table 1: Baseline Characteristics

The primary outcome, major bleeding within 24 hours of thrombolytic administration, occurred in six patients in the tenecteplase group and one in the alteplase group (14% vs. 3%, P = 0.228; (Table 2)). Major bleeding events included hemorrhagic transformation (tenecteplase n = 4), parenchymal hematoma (tenecteplase n = 1, alteplase n = 1), and subarachnoid hemorrhage (tenecteplase n = 1). No patients met the definition of major bleeding secondary to blood transfusion requirements. Other bleeding events during admission were experienced by two patients who received tenecteplase and one who received alteplase (any bleeding event during admission: n = 8 (19%) vs. n = 2 (7%), P = 0.511). The additional bleeding events in the tenecteplase group were scattered petechial hemorrhage within the subarachnoid space at greater than 24-hours and superficial bleeding, bruising, and vaginal bleeding. In the alteplase group, a patient developed a supraorbital hematoma post-alteplase administration in the setting of presenting secondary to a fall with facial trauma. The median ICU length of stay was two days (IQR 1-3) for both groups (P = 0.983). Two in-hospital deaths occurred in the tenecteplase group, and zero deaths occurred in the alteplase group (5% vs. 0%, P = 0.510). None of the deaths were attributable to the thrombolytic administration. There were no reported incidences of angioedema or hypersensitivity reactions in the study population.

|

Tenecteplase (n=42) |

Alteplase (n=29) |

P value |

|

|

Primary Outcome |

|||

|

Major Bleeding, No. (%) |

6 (14.3) |

1 (3.4) |

0.228 |

|

Secondary Outcomes |

|||

|

Any bleeding events during admission, No. (%) |

8 (19) |

2 (6.9) |

0.511 |

|

ICU Length of Stay, median (IQR), days |

2 (1-3) |

2 (1-3) |

0.938 |

|

In hospital mortality, No. (%) |

2 (4.8) |

0 (0) |

0.510 |

|

Hypersensitivity reaction, No. (%) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0) |

1.000 |

|

Angioedema, No. (%) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0) |

1.000 |

|

Abbreviations: ICU, Intensive Care Unit |

|||

Table 2: Primary and Secondary Outcomes

Discussion

Several prospective, randomized trials, including ATTEST, NORTEST, EXTEND-IA TNK, and AcT assessed tenecteplase for the treatment of AIS [7,8,10,11]. No differences in efficacy or safety between tenecteplase and alteplase were noted [7,8,10, 11]. This study assessed the safety outcomes of the use of tenecteplase for AIS and found similar rates of bleeding at 24 hours. There were also no differences in other safety outcomes, such as bleeding after 24 hours or all-cause mortality. This is consistent with previous literature and suggests that tenecteplase may be a safe alternative to alteplase in AIS patients with practical advantages, such as easier administration, prolonged half-life, and decreased cost.

While the rates of bleeding were statistically similar between the two groups, there was a numerical increase in bleeding in the tenecteplase group. One contributing factor to this increase could be a higher pretreatment NIHSS in the tenecteplase group, reflecting a higher risk of hemorrhagic conversion [12]. This is due to the NIHSS likely indicating more extensive tissue damage and larger baseline infarcts [12]. The five tenecteplase patients who experienced hemorrhagic transformation in the first 24 hours had a median pretreatment NIHSS of 10 (4-14). Based on a study by Kidwell et al, this correlates with a rate of hemorrhagic transformation of 13% [12]. An additional factor influencing this difference may have been an increase in mechanical thrombectomy rates in patients receiving tenecteplase. Mechanical thrombectomy is a known risk factor for bleeding due to potential for rapid reperfusion and the possibility of mechanical vessel stress [13]. Two out of six tenecteplase patients and the one alteplase patient who experienced a major bleed underwent thrombectomy. These differences highlight that patients in the tenecteplase group may have had a higher baseline risk of bleeding. Current use of oral anticoagulants within the last 48 hours is a contraindication to thrombolytics per the guidelines. While all patients reported non-adherence to this home medication, no laboratory data was present to fully exclude home use. Ultimately, one patient with an anticoagulant prescribed outpatient suffered major bleeding following the administration of tenecteplase.

The study center also underwent institutional changes, which may have contributed to the change in patient population noted between the two groups, including the closure of the only other primary stroke center in the area and the opening of a dedicated neurocritical care unit. Additionally, the study institution did not previously have thrombectomy capabilities, leading to patients being transported to another local facility for thrombectomy prior to being transported back to the study hospital. In 2023, the institution implemented an in-house thrombectomy program. These factors contributed to the increase in patient volume year over year (29 patients to 42 patients) and the overall higher complexity (NIHSS increased from five to eight). These changes aligned with the change of the formulary preferred agent from alteplase to tenecteplase, which may further contribute to the numerical increase observed in major bleeding for the patients receiving tenecteplase.

This study contributes to a growing body of evidence comparing FDA-approved thrombolytics but examines a patient population that remains underrepresented in existing data. This study examines the effects of alteplase, a historical standard of care, in a cohort with less severe strokes as compared to tenecteplase, a newly FDA-approved agent in patients with more severe presentations. This highlights real-world variability in patient populations. The study cohort was further distinguished by a generally younger population of Black males with predominantly mild-to-moderate NIHSS scores, providing insight into a clinically relevant and underexplored subgroup.

This study was a retrospective cohort which inherently suffers from potential design biases. Additionally, data were derived from a single center, leading to a limited patient population available for analysis that was compounded by the study site’s recent transition to tenecteplase. These characteristics may overall lower the generalizability of the study. Retrievable data were limited to what was documented in the patient chart, which may have led to an underrepresentation of some outcomes. This may have been further exacerbated by the previously highlighted thrombectomy procedure. Any documentation from the previous facility was unavailable for review. Finally, differences in baseline characteristics may have contributed to differences in patient outcomes.

Conclusion: Bleeding is a major complication of thrombolytic administration that may contribute to an increase in morbidity and mortality. The results of this study suggest there is no difference in the rates of major bleeding or other safety outcomes in patients receiving tenecteplase versus alteplase for AIS.

Disclosure: The authors have declared no potential conflicts of interest.

Data Availability: The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable requests to the corresponding author.

Additional Information: This work was presented in part as a poster at the ASHP Midyear Conference and Exhibition held in December 2024 in New Orleans, LA.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Stroke facts. Accessed May 22, 2025.

- Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, Adeoye OM, Bambakidis NC, et al. (2019) Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: 2019 update to the 2018 guidelines for the early management of acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 50:e344-e418.

- Wardlaw JM, Murray V, Berge E, del Zoppo GJ (2014) Thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD2000213.

- Genentech (2025) FDA approves Genentech’s TNKase® in acute ischemic stroke in adults. Published March 3, 2025. Accessed May 9, 2025.

- Tanswell P, Modi N, Combs D, Danays T (2002) Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of tenecteplase in fibrinolytic therapy of acute myocardial infarction. Clin Pharmacokinet. 41:1229-1245.

- Yaghi S, Willey J, Cucchiara B, Goldstein JN, Gonzales NR, et al. (2017) Treatment and outcome of hemorrhagic transformation after intravenous alteplase in acute ischemic stroke: A scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/ American Stroke Association. Stroke. 48: e343-e361.

- Huang X, Cheripelli BK, Lloyd SM, Kalladka D, Moreton FC, et al. (2015) Alteplase versus tenecteplase for thrombolysis after ischaemic stroke (ATTEST): A phase 2, randomised, open-label, blinded endpoint study. Lancet Neurol.14:368-376.

- Logallo N, Kvistad CE, Naess H, et al. (2017) The Norwegian tenecteplase stroke trial (NOR-TEST): A phase 3, randomized, openlabel, blinded endpoint trial. Lancet Neurol. 16:781-788.

- Campbell BCV, Mitchell PJ, Churilov L, Yassi N, Kleinig TJ, et al. (2020) Effect of intravenous tenecteplase dose on cerebral reperfusion before thrombectomy in patients with large vessel occlusion ischemic stroke: The EXTEND-IA TNK part 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 323:1257-1265.

- Menon BK, Buck BH, Singh N, Deschaintre Y, Almekhlafi MA, et al. (2022) Intravenous tenecteplase compared with alteplase for acute ischaemic stroke in Canada (AcT): a pragmatic, multicentre, openlabel, registry-linked, randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 400:161-169.

- Campbell BCV, Mitchell PJ, Churilov L, Yassi N, Kleinig TJ, et al. (2018) Tenecteplase versus Alteplase before Thrombectomy for Ischemic Stroke. N Engl J Med. 378:1573-1582.

- Kidwell CS, Saver JL, Carneado J, Sayre J, Starkman S, et al. (2002) Predictors of hemorrhagic transformation in patients receiving intraarterial thrombolysis. Stroke. 33:717-724.

- Linfante I, Cipolla M (2016) Improving reperfusion therapies in the era of mechanical thrombectomy. Transl Stroke Res. 7:294-302.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.