Case Report: Successful Medical Management of a Traumatic 360-Degree Cyclodialysis Cleft in a Pediatric Patient

by Lamia Alhijji1*, Fawzia Alhaimi1, Ghadah Alsuwailem2

1Department of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, King Khaled Eye Specialist Hospital, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

2College of Medicine, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

*Corresponding author: Lamia Alhijji, Department of Pediatric ophthalmology and strabismus, King Khaled eye specialist hospital, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Received Date: 03 December 2024

Accepted Date: 06 December 2024

Published Date: 09 December 2024

Citation: Alhijji L, Alhaimi F, Alsuwailem G (2024) Case Report: Successful Medical Management of a Traumatic 360-Degree Cyclodialysis Cleft in a Pediatric Patient. Ann Case Report. 9: 2106. https://doi.org/10.29011/2574-7754.102106

Abstract

Cyclodialysis cleft is a rare complication of ocular trauma characterized by disinsertion of the ciliary body from the scleral spur, leading to persistent ocular hypotony. Small clefts of less than 4° may respond to medical management; however, larger clefts often require surgical intervention. We report the case of a 9-year-old boy who presented with a traumatic 360-degree cyclodialysis cleft following blunt ocular trauma. Conservative medical management was initiated using topical steroids and atropine. Remarkably, 11 days post-trauma, ultrasound biomicroscopy confirmed the complete closure of the cyclodialysis cleft without surgical intervention.

Introduction

Cyclodialysis cleft is a rare and challenging condition, characterized by the disinsertion of the longitudinal fibers of the ciliary muscle from the scleral spur. This disinsertion results in direct communication between the anterior chamber and the suprachoroidal space, leading to the drainage of aqueous humor. The formation of this new drainage channel increases uveoscleral outflow, potentially causing chronic ocular hypotony, which is defined as an intraocular pressure (IOP) of less than 6.5 mmHg [1,2]. Well-recognized complications associated with chronic ocular hypotony include choroidal effusion, cystoid macular edema, optic nerve edema, engorgement and stasis of retinal veins, retinal folds, shallow anterior chamber, and cataract formation. Ciliary body detachment should be suspected in cases of severe ocular trauma, particularly when associated with hyphema, iris injuries, and hypotony [3,4,5]. Cyclodialysis clefts typically occur in three clinical scenarios: as a complication of surgery, particularly glaucoma surgery, or following ocular trauma.

Traumatic cyclodialysis cleft is one of the least common outcomes of blunt ocular trauma, with an incidence ranging between 1-11% [6]. Diagnosing cyclodialysis can be challenging; however, noninvasive diagnostic techniques, such as ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM) and anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS- OCT), have been shown to facilitate the process.

The primary goal of treatment is to close the cleft and restore the apposition of the ciliary body to the sclera, thereby increasing IOP, improving visual acuity, and preventing permanent vision loss [1,7,8]. Treatment approaches vary: some clefts close spontaneously with conservative medical management, while others necessitate more aggressive interventions, ranging from laser- based therapies to surgical procedures. Conservative medical treatment utilizing systemic steroids, topical steroids, and atropine to reduce ciliary and anterior segment inflammation is considered the initial approach. However, this treatment course may extend for 6-8 weeks, and its success is relatively uncommon [6]. In more severe cases, invasive techniques are often required to restore normal IOP. These include laser treatments or surgical interventions, with the choice of therapy depending on factors such as the extent of morphological or functional complications caused by hypotony [7,9,10]. According to the literature, traumatic total ciliary body detachments seldom respond to medical management and typically require surgical intervention [7]. Here, we present a case of a 360-degree cyclodialysis cleft that was successfully treated with conservative medical therapy, achieving complete and rapid closure within 11 days. To our knowledge, such a rapid resolution through medical treatment alone has rarely been reported.

Case Presentation

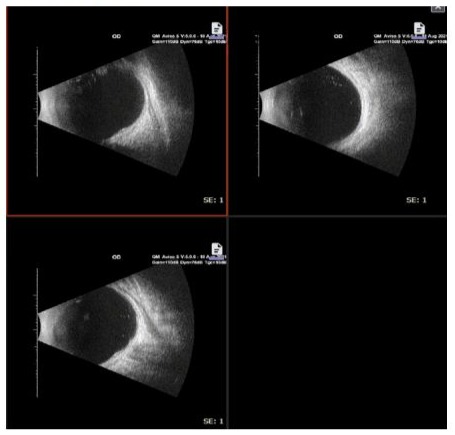

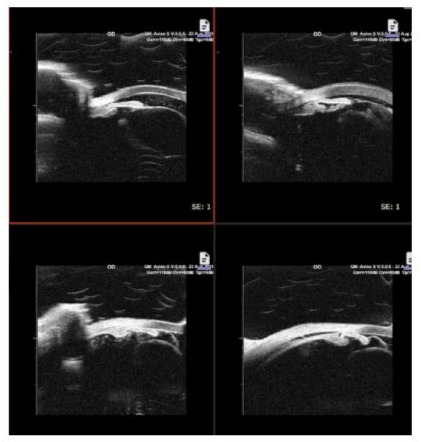

A 9-year-old boy presented to the emergency department with painful vision loss following blunt trauma caused by a rock in the right eye. On ophthalmic examination, the best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was hand motion at one foot in the right eye (OD), while the left eye (OS) was 20/20. The right eye was softer than the left eye, and accurate IOP measurements could not be obtained because of the low IOP, necessitating digital measurements. The slit-lamp findings of the right eye included normal eyelids, injected conjunctiva with a corneal epithelial defect, a shallow anterior chamber with minimal hyphema, and a cataractous lens. Fundoscopy was hampered by media opacity. Slit-lamp examination of the left eye revealed normal results. Eye movements were normal and painless. B-scan ultrasonography of the right eye showed mild vitreous hemorrhage over the macula, with extremely mild vitreous opacity, no retinal detachment, and no other abnormalities (Figure 1). UBM of the right eye revealed 360-degree closed angles and 360-degree choroidal effusion with total ciliary body detachment (Figure 2).

Treatment and Follow-Up

Once ciliary body detachment was identified, conservative medical treatment was initiated, and hypotony was closely observed. Topical prednisolone acetate 1% was administered four times daily, and atropine 1% was administered three times daily. A bandage contact lens was placed, and moxifloxacin eye drops were prescribed for corneal epithelial defects. At the third followup, 11 days after the trauma, visual acuity was light perception in the right eye (OD) and 20/25 in the left eye (OS). IOP measured with iCare was 18 mmHg (OD) and 16 mmHg (OS). The right eye still had a shallow anterior chamber and an irregular pupil due to a ruptured sphincter muscle.

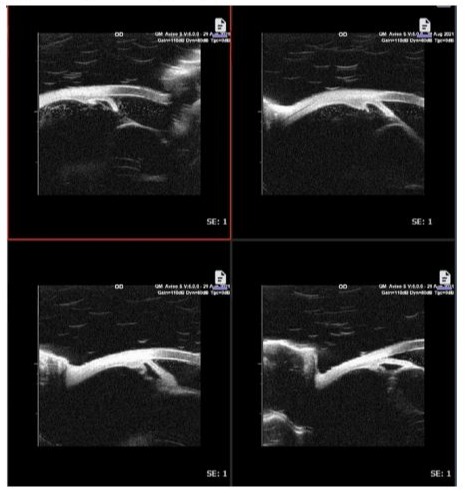

However, UBM of the right eye revealed a reattachment of the ciliary body and closure of the cyclodialysis cleft (Figure 3). Topical prednisolone was tapered, and conservative treatment was continued until the day of lens aspiration surgery for the traumatic cataract.

Outcome

Five months later, post-lens aspiration, anterior vitrectomy, and IOL implantation (OD), his best- corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20/80 in the right eye and 20/20 in the left eye. The IOP was 21 mmHg in both eyes (OU). On examination, both eyes were within normal limits.

Figure 1: Ultrasound B-scan of the right eye showing normal findings.

Figure 2: Ultrasound Biomicroscopy showing total ciliary body detachment.

Figure 3: Ultrasound biomicroscopy of the same eye (OD) 11 days after trauma showed no ciliary body detachment.

Discussion

Cyclodialysis cleft (CC) management focuses on restoring the anatomical and functional integrity of the ciliary body to re-establish normal intraocular pressure (IOP) and prevent complications like hypotony and vision loss. Ocular hypotony secondary to blunt trauma can occur due to various mechanisms, such as the failure of aqueous humor production or significant leakage from the injury site [11].

According to Ramulu et al., the prognosis of traumatic cyclodialysis cleft depends on various factors, including the extent of involvement and any associated ocular injuries. The management of cyclodialysis cleft requires a stepwise approach, beginning with the identification of the cleft’s full extent and location. In any patient presenting with persistent ocular hypotony after trauma, cyclodialysis cleft should be suspected, particularly following surgical or non-surgical trauma [7]. Imaging techniques, notably ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM) and anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT), have significantly improved diagnostic accuracy, helping clinicians visualize the cleft and plan treatment [12].

Smaller clefts, typically less than 4 degrees, respond well to conservative medical management using topical steroids and atropine. Steroids help reduce inflammation and prevent complications like choroidal effusion, while atropine relaxes the ciliary muscle and promotes reattachment of the ciliary body to the sclera by increasing scleral contact [1-3]. According to a study by Trikha et al., larger clefts or those that do not respond to conservative treatment require surgical intervention. Surgical options include cyclopexy, where sutures are used to directly reattach the ciliary body, or laser photocoagulation, which induces scarring to close the cleft [4]. For more severe cases, where conservative or standard surgical interventions do not suffice, advanced techniques may be necessary. Grosskreutz et al. reported the successful use of suprachoroidal space drainage to manage persistent hypotony due to fluid accumulation despite anatomical correction of the cleft [6]. In cases where surgical repair is required, Nagashima et al. described the efficacy of ciliary body suturing to successfully manage traumatic cyclodialysis clefts [10].

Medeiros et al. highlighted the role of vitrectomy with endotamponade, which involves injecting silicone oil to stabilize IOP and manage hypotony, especially in cases where choroidal detachment is present [12]. The early detection and intervention of cyclodialysis clefts are critical in improving outcomes. While medical management is a preferred initial therapy, failure to achieve anatomical closure or sustained IOP correction often necessitates early surgical intervention, especially in cases of extensive cyclodialysis or ciliary body detachment [12,13]. In our case, despite the 360-degree extent of the cleft, conservative medical therapy led to reattachment of the ciliary body within 11 days, as confirmed by UBM, highlighting the potential for nonsurgical resolution in select cases. Our patient underwent cataract surgery after stabilization of intraocular pressure and reattachment of the ciliary body, and the visual outcome was satisfactory, since there was no documented vision baseline prior to the trauma, the final BCVA of 20/80, despite a normal and stable post-surgical examination, suggests the possibility of amblyopia. Ultimately, early and individualized treatment strategies, supported by imaging techniques, offer the best chance for successful outcomes.

Conclusion

In this case, the patient presented with a traumatic 360-degree cyclodialysis cleft, which is a rare condition. Despite the extensive cleft, conservative medical treatment with topical steroids and atropine led to a complete closure of the cleft within 11 days. This rapid response to medical management is uncommon in large clefts, where surgical repair is typically required. This case underscores the importance of individualized treatment strategies and suggests that early intervention, even in cases with extensive clefts, can sometimes eliminate the need for surgical procedures. It also reinforces the potential effectiveness of medical therapy in specific cyclodialysis cleft cases, challenging the traditional reliance on surgical solutions for larger or traumatic clefts.

Acknowledgements: Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions: Authors’ Contributions Lamia Alhijji, Fawzia Alhaimi, Ghadah Alsuwailem, have contributed equally to this work and should be considered as equal Co-authors.

Design of the work (Lamia Alhijji, Fawzia Alhaimi, Ghadah Alsuwailem) Acquisition, analysis, interpretation of data (Lamia Alhijji, Fawzia Alhaimi, Ghadah Alsuwailem). Drafting the work and substantively revision (Lamia Alhijji, Fawzia Alhaimi, Ghadah Alsuwailem). All the authors read and approved the final manuscript. (Lamia Alhijji, Fawzia Alhaimi, Ghadah Alsuwailem)

Funding: All authors have declared that no financial support was received from any organization for the submitted work.

Data availability: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author (Dr. Alhijji).

Declarations Competing interests: The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This case study followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of the King Khaled Eye Specialist Hospital reference number [RD/26001/IRB/0360- 23] The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient and gaurdians have their consent for their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patient and gaurdians understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

References

- González-Martín-Moro J, Contreras-Martín I, Muñoz-Negrete FJ, Gómez-Sanz F, Zarallo- Gallardo J. (2017) Cyclodialysis: An update. Int Ophthalmol. 37:441-457.

- Wang Q, Thau A, Levin AV, Lee D. (2019) Ocular hypotony: a comprehensive review. Surv Ophthalmol. 64:619-638.

- Pavlin CJ. (2011) Ciliary body detachment. Ophthalmology. 118:20972097.

- Trikha S, Turnbull AM, Agrawal SS, Amerasinghe N, Kirwan JF. (2012) Management challenges arising from a traumatic 360-degree cyclodialysis cleft. Clin Ophthalmol. 6:257-60.

- Ramulu PY, Jun A, Fekrat S, Scott IU. Cyclodialysis cleft after trauma. EyeNet [Internet].

- Grosskreutz C, Aquino N, Dreyer EB, et al (1995) Cyclodialysis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 35:105–9.

- Ioannidis AS, Barton K. (2010) Cyclodialysis cleft: causes and repair. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 21:150-4.

- Ioannidis AS, Bunce C, Barton K. (2014) The evaluation and surgical management of cyclodialysis clefts that have failed to respond to conservative management. Br J Ophthalmol. 98:544-9.

- Pinheiro-Costa J, Melo AB, Carneiro ÂM, Falcão-Reis F. (2015) Cyclodialysis cleft treatment using a minimally invasive technique. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 6:66-70.

- Nagashima T, Kohmoto R, Fukumoto M, Oosuka S, Sato T, et al (2020) Ciliary body suturing using intraocular irrigation for traumatic cyclodialysis: two case reports. J Med Case Rep.14:121.

- Ding C, Zeng J. (2012) Clinical study on hypotony following blunt ocular trauma. Int J Ophthalmol. 5:771-3.

- Medeiros MD, Postorino M, Pallás C, Salinas C, Mateo C, et al (2013) Cyclodialysis induced persistent hypotony: surgical management with vitrectomy and endotamponade. Retina. 33:1540-6.

- Meng LN, Dong XG. (2013) Ciliary body detachment after secondary intraocular lens implantation in childhood. Int J Ophthalmol. 6:895-6.

- Ning L, Wen Y, Lan L, Yang Y, Chen T, et al (2022) Effect of different preoperative intraocular pressures on the prognosis of traumatic cyclodialysis cleft associated with lens subluxation. Ophthalmol Ther. 11:689-699.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.