Case Report: Homocysteine Reduction in 7 Patients Using a Hcy-Supporting Nutraceutical

by Michael Jurgelewicz1*, Oscar Coetzee2

1Department of Human Nutrition, University of Bridgeport, CT, USA

2Department of Health Science, University of Bridgeport, CT, USA

*Corresponding Author: Michael Jurgelewicz, Department of Human Nutrition, University of Bridgeport, CT, USA

Received Date: 01 December 2025

Accepted Date: 04 December 2025

Published Date: 09 December 2025

Citation: Jurgelewicz M, Coetzee O. (2025). Case Report: Homocysteine Reduction in 7 Patients Using a Hcy-Supporting Nutraceutical. Ann Case Report. 10: 2467. DOI: https://doi.org/10.29011/2574-7754.102467

Abstract

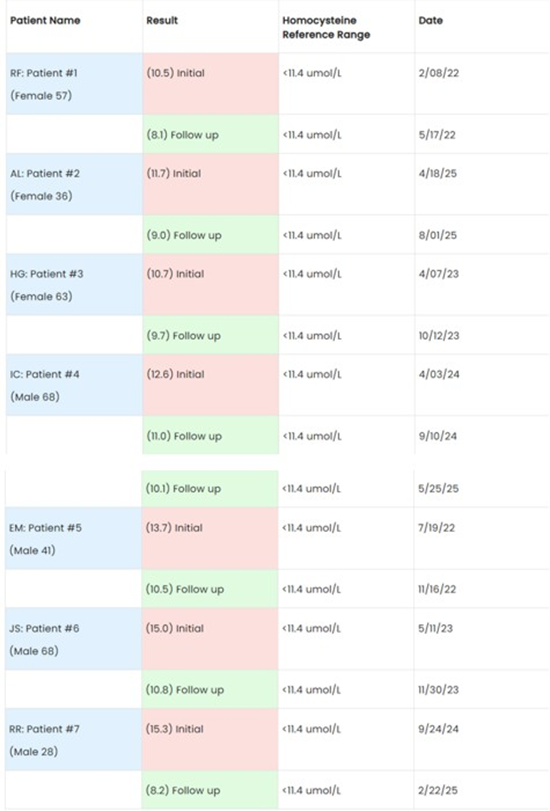

In a recent meta-analysis of prospective studies, it was found that elevated homocysteine (Hcy) levels appear to be an independent predictor for subsequent cardiovascular mortality and/or all-cause mortality. Coronary heart disease showed an increase at 66%, cardiovascular mortality at 68%, and all-cause mortality at 93%. Currently there is no standard of care pharmaceutical in place to treat elevated Hcy. In this case report seven patients of different genders and age groups from the Bucks County Center for Functional Medicine, Holland, PA, with varying medical conditions, but with one common denominator of elevated homocysteine were put on a Hcy lowering nutraceutical. The outcome of this case report indicates a potential intervention for elevated Hcy by using this nutraceutical. The individual outcomes of each patient indicated positive results. Patient # 1 (RF): 10.5 umol/L reduced to 8.1 umol/L (3 months) - 22.86%, Patient # 2 (AL): 11.7 umol/L reduced to 9.0 umol/L (3.5 months) - 23.08%, Patient #3 (HG): 10. 7 umol/L reduced to 9.7 umol/L (6 months) - 9.35%, Patient #4 (IC): 12.6 umol/L reduced to 10.1 umol/L (5 months) - 19.84%, Patient #5 (EM): 13.7 umol/L reduced to 10.5 umol/L (4 months) - 23.36%, Patient #6 (JS): 15.0 umol/L reduced to 10.8 umol/L (6 months) - 28.00%, Patient #7 (RR): 15.3 umol/L reduced to 8.2 umol/L (5 months) - 46.40%, that is an average of reduction of 3.3 umol/L(-24.70%)

Keywords: Hcy Reduction; Cardiovascular Disease; Cardiovascular Disease; Metabolic Disorders; DNA Methylation.

Introduction

This case report is a retrospective review of seven patients from Bucks County Center for Functional Medicine, Holland, PA, with a variety of symptoms and medical conditions. However, one common denominator in all patients was their elevated homocysteine (Hcy). Hcy is an indicator of systemic inflammation, with strong correlations to cardiovascular disease, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic disorders [1].

History

Homocysteine was discovered in 1932 by Butz and du Vigneaud during their work studying methionine decomposition. In the 1960s, further improvement in science led to the discovery of homocystinuria, a genetic disorder where the defect causes severe metabolic issues. In the 1970s methods were developed to measure Hcy in blood for a potential indicator in cardiovascular disease (CVD). Finally, Kilmer McCully proposed the “homocysteine theory of atherosclerosis” [2].

Current allopathic medical therapies of Hcy reduction lack significant or consistent outcomes, and there are no standards of care treatment [3]. However, the consistent correlation still makes it a valuable biomarker for assessing cardiovascular and metabolic risk, especially in at-risk populations.

In a recent meta-analysis of prospective studies, it was found that elevated Hcy levels appears to be an independent predictor for subsequent cardiovascular mortality and/or all-cause mortality.

Coronary heart disease showed an increase at 66%, cardiovascular mortality at 68%, and all-cause mortality at 93% [4].

Homocysteine and Health

The sulfhydryl-containing amino acid homocysteine is a substrate and product of the amino acid methionine, and it plays a key role in the methylation cycle.5 Methionine converts into Hcy through S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), which is an important methyl donor in biochemical processes, including DNA methylation. Homocysteine is re-methylated into methionine when more methionine is required or converted into cysteine by transsulfuration. These processes require B-vitamins, including riboflavin, vitamin B6, folate, and vitamin B12 [5,6]

Hyperhomocysteinemia, or high Hcy levels, may occur due to a variety of factors that impair the remethylation and/or transsulfuration pathways.5 Dietary and lifestyle factors include poor diet, high protein, and/or methionine intake, B vitamin deficiencies, smoking, and physical inactivity. Genetic polymorphisms, especially those that code for methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR), may also elevate Hcy levels above optimal [5,6]. Increased age, certain diseases, and medications may also contribute to the risk of hyperhomocysteinemia [6].

Increasing levels of Hcy may lead to the conversion of homocysteine into homocysteine thiolactone, which is a more toxic metabolite [5]. Homocysteine thiolactone is highly reactive with several proteins and may alter their activity, which may cause dysfunction. Increased Hcy levels may also contribute to inflammation and excess oxidative stress, as Hcy increases the production of reactive oxygen species and nitrogen species [5,7].

Studies have found that high Hcy levels are associated with an increased risk of chronic conditions, including cardiovascular disease, stroke, cognitive decline, depression, migraine, systemic lupus erythematosus, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and neurological disorders [5,7, 8-15]. One study investigated the potential for Hcy to be a marker of cardiovascular disease risk. The researchers found it had a high sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy, providing an 89% positive predictive value and 39.48 odds ratio for Hcy in cardiovascular patients compared to other risk factors, which included high sensitivity C-reactive protein, lipoprotein(a), hemoglobin A1c, blood lipids, and anthropometric and demographic parameters [16]. Supporting the methylation pathways, for example with nutrients such as those in Designs for Health’s Homocysteine Supreme™, may promote healthy Hcy levels.* A meta-analysis found that supplementation of B vitamins led to a reduction of Hcy levels [8].

Narrative

The cases of seven patients with elevated homocysteine were retrospectively reviewed for this report:

Patient#1: RF (57-year-old female): Patient presented with back pain, hot flashes, osteoporosis, and numbness in the left thumb. Her medical history consisted of dyslipidemia, hypertension, cancer, and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Lifestyle factors include no regular exercise, nonsmoker, does not drink alcohol, and no adherence to a specific diet. Medications for thyroid, hypertension, allergies, statin, and estrogen-regulating.

Patient #2: AL (36-year-old female): Patient presented hair loss attributed to lichen planopilaris or possible androgenic and scarring alopecia due to inflammation. AL does not exercise regularly, consumes approximately 4–6 alcoholic drinks per week, and is a non-smoker. Elevated lipids, headaches and diet appear to be high glycemic, with recent elimination of gluten and dairy. Medications for depression, blood pressure, seasonal allergies, and corticosteroid cream were used prior to initial visit.

Patient #3: HG (63-year-old female): Patient presented with gastrointestinal concerns, including gastritis, constipation, high cholesterol, nausea, bloating, gas, and delayed gastric emptying, with minimal improvement despite prior efforts. HG did not engage in regular exercise over the past six months, smokes approximately half a pack of cigarettes per day, does not consume alcohol, and does not follow a specific diet. Medications for thyroid, anxiety, PPIs for gastritis.

Patient #4: IC (68-year-old male): The patient presented for an initial consultation seeking support for myasthenia gravis, with symptoms limited to ocular involvement and no progression. IC maintains regular physical activity, exercising approximately four times per week (jogging/walking 30–45 minutes) and participating in sports three times per week (15–30 minutes). IC consumes 4–6 alcoholic drinks per week, does not smoke, and does not follow a specific diet.

Patient #5: EM (41-year-old male): The patient presented with longstanding symptoms of anxiety and depression, occurring several times per month. EM has a history of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and has been treated with Synthroid for the prior six years. Over the past year, EM has also developed dermatological concerns including eczema, psoriasis, and pigmentation changes, likely related to underlying gut dysfunction and autoimmunity. EM participates in physical activity twice weekly with 30 minutes of strength training, and once weekly with 45 minutes of aerobic exercise. Lifestyle factors include cigarette smoking, alcohol intake of 7–10 drinks per week, and no adherence to a specific diet.

Patient #6: JS (68-year-old male): The patient presented seeking support for longstanding gastrointestinal issues persisting over the past 20 years. JS began a gluten-free diet several years ago, which has led to slight improvement. Current symptoms include bloating, bowel irregularities, gas, and abdominal pain. JS was previously diagnosed with diabetes and dyslipidemia, hypertension, all wellcontrolled with medication, as well as atrial flutter, for which JS has undergone multiple procedures. Lifestyle factors include no regular exercise, non-smoker, alcohol intake of 4–6 drinks per week, and adherence to a gluten-free diet.

Patient #7: RR (28-year-old male): Patient was diagnosed with vitiligo four years prior. Previous treatment with multiple topical steroid creams prescribed by a dermatologist was ineffective. He also trialed dietary interventions, including a restricted carnivore diet, but his condition continued to worsen. His medical history includes vitamin D deficiency and elevated thyroid peroxidase antibodies. Lifestyle factors include regular exercise (jogging/ walking three times per week for 30 minutes and strength training four times per week for 45 minutes), smoking 5–10 cigarettes per day, abstaining from alcohol, and adherence to a gluten-free diet for one year. Other symptoms were fatigue, headaches, and UTIs.

Clinical Findings

A consistent finding in the seven cases was that of elevated Hcy at the start of the intervention:

Patient # 1 (RF): 10.5 umol/L

Patient # 2 (AL): 11.7 umol/L

Patient #3 (HG): 10. 7 umol/L

Patient #4 (IC): 12.6 umol/L

Patient #5 (EM): 13.7 umol/L Patient #6 (JS): 15.0 umol/L

Patient #7 (RR): 15.3 umol/L

Several other commonalities in these cases that might be drivers of elevated Hcy were observed. ETOH use was found in 4/7 cases, habitual smoking in 3/7 cases, dyslipidemia/hypercholesterolemia in 4/7 cases. Alcohol consumption has been associated to Hcy elevation, mostly due to its interference with methionine metabolism and its impact on essential B vitamins like folate, riboflavin, and B12 that are necessary for the regulation of the “Homocysteine Folate Cycle” [17].

In the same manner, smoking may increase Hcy levels, which increases risks for cardiovascular disease, stroke, and coronary artery disease. It is known that smoking lowers levels of B vitamins, especially B12 and folate which are essential for the “Homocysteine Folate Cycle.” Smoking cessation has been associated with significant reduction in Hcy levels [18].

Strong causal associations have been found in various types of hyperlipidemias including high total cholesterol, high LDL-C, and elevation of Hcy. Across the spectrum of cholesterol subfraction levels and elevated Hcy there is evidence of increased cardiovascular disease [19].

Smoking and alcohol consumption significantly reduce glutathione levels. Alcohol metabolism generates toxic byproducts that deplete glutathione, while cigarette smoke contains components that irreversibly react with and deplete glutathione. Both these habits increase oxidative stress and reactive oxygen species, leaving the body more vulnerable to lower antioxidant levels [20].

Elevated Hcy is associated with impaired nitric oxide synthesis, which contributes to blood vessel damage, and decreased glutathione can reduce the body's ability to neutralize harmful free radicals. Modulating glutathione levels through N-acetylcysteine or reduced glutathione can lower homocysteine [21,22].

Even though ETOH, smoking and antioxidants were not directly addressed in these cases, they might be additional interventions for the future in homocysteine regulation and normalization. For these cases, the common intervention to address elevated homocysteine was the intake of Homocysteine Supreme™ 1 capsule TIB.

Patient # 1 (RF): 10.5 umol/L reduced to 8.1 umol/L (3 months) - 22.86%

Patient # 2 (AL): 11.7 umol/L reduced to 9.0 umol/L (3.5 months) - 23.08%

Patient #3 (HG): 10. 7 umol/L reduced to 9.7 umol/L (6 months) - 9.35%

Patient #4 (IC): 12.6 umol/L reduced to 10.1 umol/L (5 months) - 19.84%

Patient #5 (EM): 13.7 umol/L reduced to 10.5 umol/L (4 months) - 23.36%

Patient #6 (JS): 15.0 umol/L reduced to 10.8 umol/L (6 months) - 28.00%

Patient #7 (RR): 15.3 umol/L reduced to 8.2 umol/L (5 months) - 46.40%

That is an average of reduction of 3.3 umol/L (-24.70%)

Timeline

Patient Perspectives

RF: I have seen a huge improvement in our overall health and quality of life. At first, the change was very difficult but as the time went by, it became much easier to embrace all the good things in life. I lost over 35 lbs without any effort, just stick to the plan and do not eat the foods that your body is reacting to. When I had an issue with a cardiologist, Dr. J saw that I was really stressed, and he took the time to go over the results and make appropriate recommendations. He does not guess on anything, everything is justified and backed by lab work. I know for certain that if you want your life to change to become healthier and happier person, he is definitely a person to turn to.

AL: I had tried medication without success. Once I addressed the inflammation and nutrition and through the diet, I was able to stop the prescribed medications, and I am seeing some improvements in hair growth and overall health.

HG: For years, I struggled with stomach pain, bloating, and constipation. Medications only gave me temporary relief. After watching what I ate and making dietary adjustments I lost 8 lbs and feel much better.

IC: When I was diagnosed with myasthenia gravis, I was determined to do everything I could to keep it from progressing. I have been following a nutritional approach to address the lowgrade inflammation. I currently do not have any symptoms, and I feel great and in control of my health.

EM: I have had anxiety and depression as well as fatigue for years. By focusing on my gut health through diet and supplementation, I have noticed improvements in my mood and overall health.

JS: I have had stomach problems for the past 20 years, and nothing seemed to help long-term. I previously went on a gluten-free but only experienced a slight improvement. By making more targeted adjustments with my diet, I feel better and do not have to take MiraLAX® every morning.

RR: When I was diagnosed with vitiligo, I was given several steroid creams by a dermatologist, and they did not work. I also tried a carnivore diet, and my symptoms have been worsening. After taking an alternative approach that focuses on the whole person and my gut health, I am starting to feel better.

Discussion

Currently there is no pharmaceutical in place to treat elevated Hcy; thus, several practitioners have resorted to alternative therapies.

Therapeutic Intervention: All patients took Homocysteine Supreme™ from Designs for Health at a dose of 1 capsule BID with meals; however, some of their other interventions were totally different due to various clinical conditions, with the only consistent intervention in all seven cases being the Homocysteine Supreme™. One may postulate that the nutraceutical had a commonality in the outcome of Hcy improvement. Dosing remained consistent through all participants, regardless of age, sex, or weight. An interpretation and review of the constituents/ingredients in Homocysteine Supreme™ will be discussed below to potentially elucidate the association to success with these patients in Hcy reduction, since it is the main commonality in these cases, in patients that have not been able to reduce it with any prior treatments.

Folate

5-methyltetrahydrofolate (5-MTHF), the active form of folate, is a methyl group donor in the remethylation of methionine. Homocysteine takes the methyl group from 5-MTHF to form new methionine.5 Lower plasma or serum folate levels are associated with higher Hcy levels, especially in populations with conditions associated with hyperhomocysteinemia [14,23,24]. One meta-analysis found an inverse association between dietary intake of folate and stroke risk, likely due to its influence on Hcy metabolism. The highest intake of dietary folate correlated with a 15% lower risk of stroke compared to the lowest category, and each 100 μg/day increase in dietary folate led to a 6% reduction in stroke risk [25]. One study concluded that increasing folate levels by 200 μg through diet or supplementation significantly reduced Hcy levels [26]. This may be more important in those with 5-MTHFR genetic polymorphisms. A study on couples with infertility problems found that taking 5-MTHF supplements significantly reduced Hcy levels in the participants who were heterozygous or homozygous for the C677T SNP in the MTHFR gene [27].

Vitamin B12

Vitamin B12 plays a key role as a cofactor for important enzymes involved in cellular metabolism and methylation. Methylcobalamin is the cofactor for the vitamin B12-dependent enzyme, methionine synthase [28]. Methionine synthase is involved in the first step of the methionine cycle, converting methionine to SAM.5 Cobalamin-independent methionine synthase has a much slower turnover in comparison [28]. There may be an inverse association between lower serum levels of vitamin B12 and Hcy level [14,23,29]. One randomized, multi-arm, open-label clinical trial on 40 patients with type 2 diabetes tested adding B vitamin supplementation to standard anti-diabetic medications. The groups taking 500 mcg of methylcobalamin alone or with 5 mg folic acid daily for eight weeks experienced significant improvement in hemoglobin A1c levels, plasma insulin, and serum adiponectin compared to the control group. The three vitamin B groups also experienced a significant reduction of Hcy levels compared to the controls [30].

Trimethylglycine (TMG)

Also known as betaine, trimethylglycine is a metabolite of choline. It acts as a methyl donor for the conversion of Hcy into methionine in the remethylation pathway [31]. One study found a significant inverse association between serum betaine levels and Hcy levels, independent of folate and vitamin B12 levels, demonstrating it may be a significant determinant of Hcy levels [32]. Another study found that higher betaine intake is associated with lower Hcy levels, especially in those with vitamin B12 and folate deficiencies. The median betaine intake was 203 mg/day for the highest intake group [33]. One study found that 3 g of betaine, 30 mg of vitamin B6, 200 μg of vitamin B12, and 5 mg of folic acid supplementation significantly lowered Hcy levels after drinking wine, an action associated with increased homocysteine levels [34].

Vitamin B6 (as Pyridoxal-5-Phosphate)

Homocysteine also goes through the transsulfuration pathway to synthesize cysteine instead. This pathway uses the enzyme cystathionine beta-synthase (CBS) to create cystathionine, which is broken down into cysteine and alpha-ketobutyrate. CBS requires vitamin B6 as a cofactor [5]. Vitamin B6 is also a co-enzyme in the folate pathway that transfers one-carbon unit from serine to tetrahydrofolate (THF) [35]. One meta-analysis found an inverse association between dietary intake of vitamin B6 and stroke risk, likely due to its influence on Hcy metabolism, with each 0.5 mg/ day increase of vitamin B6 intake correlating with a 6% reduction in the risk of stroke.25 One randomized controlled trial found that supplementing with 50 mg of pyridoxal-5-phosphate daily for 12 weeks led to a significant reduction in Hcy levels in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma post-tumor resection [36].

Riboflavin (as Riboflavin‑5‑Phosphate)

Riboflavin is a coenzyme for

5-methyltetrahydrofolate-homocysteine methyltransferase. This enzyme converts 5-MTHF back to THF in the folate pathway and converts Hcy to methionine in the remethylation cycle. Riboflavin is also a co-enzyme for THF reductase, which converts 5,10 methylene tetrahydrofolate into 5-MTHF in the folate pathway to be used as the primary methyl donor to convert Hcy back to methionine[31]. In a clinical trial, six-week supplementation of a synthetic or natural vitamin B complex that included riboflavin (in ranges of approximately 2.5 times the recommended daily allowance) significantly reduced Hcy levels[37].

Conclusion

Inflammation is a very complex condition, and the systemic origin of elevated homocysteine is still a debate in the scientific community. However, the medical community agrees on the value of investigating the levels of Hcy in blood chemistry, as it is associated with several conditions and could be an early indicator for several pathologies. Currently no standard of care is implemented in Hcy elevation, other than some data supporting the use of B12, B6, and folate, sometimes used individually and sometimes together, and with varying dosing. This case report indicated that the standard use of one dose with all sexes, weights, and ages showed improvement throughout. A patented formulation of B12, B6, B2, folate, and TMG was used with promising findings. A randomized control trial is suggested for future studies to potentially further elucidate the hypothesis laid out in this case report.

Acknowledgements: Dr. Oscar Coetzee (University of Bridgeport) and Dr. David Reilly (CARE guidelines), and Bucks County Center for Functional Medicine, Holland, PA.

Funding: No funding or grants were received to write this case report.

References

- Durand P, Prost M, Loreau N, Lussier-Cacan S, Blache D. (2001). Impaired homocysteine metabolism and atherothrombotic disease. Lab Invest. 81:645-672.

- McCully KS. (2005). Hyperhomocysteinemia and arteriosclerosis: historical perspectives. Clin Chem Lab Med. 43:980-986.

- Abraham JM, Cho L. (2010). The homocysteine hypothesis: still relevant to the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease? Cleve Clin J Med. 77:911.

- Liu D, Fang C, Wang J, Tian Y, Zou T. (2024). Association between homocysteine levels and mortality in CVD: a cohort study based on NHANES database. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 24:652.

- Djuric D, Jakovljevic V, Zivkovic V, Srejovic I. (2018). Homocysteine and homocysteine-related compounds: an overview of the roles in the pathology of the cardiovascular and nervous systems. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 96:991-1003.

- Hankey GJ. (2018). B vitamins for stroke prevention. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 3:51-58.

- Škovierová H, Vidomanová E, Mahmood S, Sopková J, Drgová A, et al. (2016). The molecular and cellular effect of homocysteine metabolism imbalance on human health. Int J Mol Sci. 17:1733.

- Huang T, Chen Y, Yang B, Yang J, Wahlqvist ML, et al. (2012). Metaanalysis of B vitamin supplementation on plasma homocysteine, cardiovascular and all-cause mortality. Clin Nutr. 31:448-454.

- Wu X, Zhou Q, Chen Q, Li Q, Guo C, Tian G, et al. (2020). Association of homocysteine level with risk of stroke: a dose-response metaanalysis of prospective cohort studies. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 30:1861-1869.

- Setién-Suero E, Suárez-Pinilla M, Suárez-Pinilla P, Crespo-Facorro B, Ayesa-Arriola R. (2016). Homocysteine and cognition: a systematic review of 111 studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 69:280-298.

- Moradi F, Lotfi K, Armin M, Clark CCT, Askari G, et al. (2021). The association between serum homocysteine and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur J Clin Invest. 51:e13486.

- Liampas I, Siokas V, Mentis AF, Aloizou AM, Dastamani M, et al. (2020). Serum homocysteine, pyridoxine, folate, and vitamin B12 levels in migraine: systematic review and meta-analysis. Headache. 60:1508-1534.

- Sam NB, Zhang Q, Li BZ, Li XM, Wang DG, et al. (2020). Serum/plasma homocysteine levels in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 39:1725-1736.

- Dong B, Wu R. (2020). Plasma homocysteine, folate and vitamin B12 levels in Parkinson’s disease in China: a meta-analysis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 188:105587.

- Dardiotis E, Arseniou S, Sokratous M, Tsouris Z, Siokas V, et al. (2017). Vitamin B12, folate, and homocysteine levels and multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 17:190-197.

- Sahu A, Gupta T, Kavishwar A, Singh RK. (2015). Cardiovascular diseases risk prediction by homocysteine in comparison to other markers: a study from Madhya Pradesh. J Assoc Physicians India. 63:37-40.

- Kamat PK, Mallonee CJ, George AK, Tyagi SC, Tyagi N. (2016). Homocysteine, alcoholism, and its potential epigenetic mechanism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 40:2474-2481.

- O’Callaghan P, Meleady R, Fitzgerald T, Graham I, European COMAC Group. (2002). Smoking and plasma homocysteine. Eur Heart J. 23:1580-1586.

- Daly C, Fitzgerald AP, O’Callaghan P, Collins P, Cooney MT, et al. (2009). Homocysteine increases the risk associated with hyperlipidaemia. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 16:150-155.

- Ignatowicz E, Woźniak A, Kulza M, Seńczuk-Przybyłowska M, Cimino F, et al. (2013). Exposure to alcohol and tobacco smoke causes oxidative stress in rats. Pharmacol Rep. 65:906-913.

- Handy DE, Zhang Y, Loscalzo J. (2005). Homocysteine down-regulates cellular glutathione peroxidase (GPx1) by decreasing translation. J Biol Chem. 280:15518-15525.

- Ovrebø KK, Svardal A. (2000). The effect of glutathione modulation on the concentration of homocysteine in plasma of rats. Pharmacol Toxicol. 87:103-107.

- Ma F, Wu T, Zhao J, Ji L, Song A, et al. (2017). Plasma homocysteine and serum folate and vitamin B12 levels in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: a case-control study. Nutrients. 9:725.

- Tsai TY, Yen H, Huang YC. (2019). Serum homocysteine, folate and vitamin B12 levels in patients with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 180:382-389.

- Chen L, Li Q, Fang X, Wang X, Min J, et al. (2020). Dietary intake of homocysteine metabolism-related B-vitamins and the risk of stroke: a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Adv Nutr. 11:1510-1528.

- Zappacosta B, Mastroiacovo P, Persichilli S, Pounis G, Ruggeri S, et al. (2013). Homocysteine lowering by folate-rich diet or pharmacological supplementations in subjects with moderate hyperhomocysteinemia. Nutrients. 5:1531-1543.

- Clément A, Menezo Y, Cohen M, Cornet D, Clément P. (2020). 5-Methyltetrahydrofolate reduces blood homocysteine level significantly in C677T methyltetrahydrofolate reductase SNP carriers consulting for infertility. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 49:101622.

- Kräutler B. (2012). Biochemistry of B12-cofactors in human metabolism. Subcell Biochem. 56:323-346.

- Upadhyay TR, Kothari N, Shah H. (2016). Association between serum B12 and serum homocysteine levels in diabetic patients on Metformin. J Clin Diagn Res. 10:BC01-BC04.

- Satapathy S, Bandyopadhyay D, Patro BK, Khan S, Naik S. (2020). Folic acid and vitamin B12 supplementation in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. 53:102526.

- Mahmoud AM, Ali MM. (2019). Methyl donor micronutrients that modify DNA methylation and cancer outcome. Nutrients. 11:608.

- Melse-Boonstra A, Holm PI, Ueland PM, Olthof M, Clarke R, et al. (2005). Betaine concentration as a determinant of fasting total homocysteine concentrations. Am J Clin Nutr. 81:1378-1382.

- Lee JE, Jacques PF, Dougherty L, Selhub J, Giovannucci E, et al. (2010). Are dietary choline and betaine intakes determinants of total homocysteine concentration? Am J Clin Nutr. 91:1303-1310.

- Rajdl D, Racek J, Trefil L, Stehlik P, Dobra J, et al. (2016). Effect of folic acid, betaine, vitamin B6, and vitamin B12 on homocysteine and dimethylglycine in men drinking white wine. Nutrients. 8:34.

- Friso S, Udali S, De Santis D, Choi SW. (2017). One-carbon metabolism and epigenetics. Mol Aspects Med. 54:28-36.

- Cheng SB, Lin PT, Liu HT, Peng YS, Huang SC, et al. (2016). Vitamin B6 supplementation mediates antioxidant capacity by reducing plasma homocysteine in hepatocellular carcinoma patients post-surgery. Biomed Res Int. 2016:7658981.

- Lindschinger M, Tatzber F, Schimetta W, Schmid I, Barbara Lindschinger B, et al. (2019). A randomized pilot trial to evaluate bioavailability of natural versus synthetic vitamin B complexes. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019:6082613.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.