Cardiovascular Adverse Events Following COVID-19 Vaccination: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

by Savi Meher*

Graded Specialist Community Medicine AFMS, India

*Corresponding author: Savi Meher, Graded Specialist Community Medicine AFMS, India

Received Date: 13 February, 2026

Accepted Date: 20 February, 2026

Published Date: 24 February, 2026

Citation: Meher S (2026) Cardiovascular Adverse Events Following COVID-19 Vaccination: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Community Med Public Health 10: 556. DOI: https://doi.org/10.29011/2577-2228.100556

Abstract

Background: COVID-19 vaccines have significantly reduced morbidity and mortality associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, concerns persist regarding rare but serious cardiovascular adverse events, particularly myocarditis, pericarditis and thromboembolic complications [1,12,14]. Objectives: To evaluate and compare the pooled incidence and relative risk of myocarditis, pericarditis and thromboembolic events following mRNA vaccine (Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna) and viral vector vaccine (AstraZeneca, Johnson & Johnson), with emphasis on age, sex related variations. Methods: A systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted as per PRISMA guidelines. A total of 11 studies including 58,620,611 individuals were included. Statistical analyses were performed, pooled incidence and relative risk estimates were calculated using a random-effects model. Heterogeneity was assessed using Cochran’s Q and I2 statistics. Publication bias was explored using funnel plots and Egger’s test where applicable. Results: mRNA vaccine was associated with a higher pooled incidence of myocarditis, particularly in males aged 18-40 years with highest pooled incidence observed with Moderna (0.0045%), followed by Pfizer (0.003%). Thromboembolic events were more frequent with viral vector vaccine, with the highest pooled incidence observed with AstraZeneca (0.0025%), particularly in older adults. Myocarditis risk was significantly more common in younger males, while no significant sex difference was noticed in thromboembolism. Conclusion: Although the incidence of cardiovascular adverse events remains low, mRNA vaccines were associated with a higher pooled incidence of myocarditis, while viral vector vaccines showed higher thromboembolic event rates. These findings support continued vaccine safety surveillance, demographic stratified risk communication,12 14 evidence informed vaccination policies.

Keywords: COVID-19 vaccine; Myocarditis; Thromboembolism; mRNA vaccine; Viral vector vaccine; Meta-analysis

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to unprecedented global efforts in vaccine development and deployment. Mass vaccination campaigns have been instrumental in reducing the burden of severe form of disease, hospitalisation and death associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection [12,14] while the safety profile of vaccines has been largely reassuring; however, post-marketing surveillance and observational studies have raised concerns regarding rare but serious cardiovascular adverse events, notably myocarditis, pericarditis and thromboembolic complications. Myocarditis and pericarditis have been reported following mRNA based vaccine (Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna) [1-4], particularly among young males following second dose. Conversely, thrombocytopenia including vaccine induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VITT), more commonly associated with adenoviral vector-based vaccines (AstraZeneca, Johnson & Johnson) [7,13]. Although these side effects are less frequent, their potential severity has prompted increased scrutiny of vaccine safety.

Understanding these variations is essential for informing public health policies and optimizing vaccine safety. This meta-analysis was undertaken to systematically evaluate and quantify the incidence of cardiovascular adverse events following COVID-19 vaccination, stratified by vaccine type, age, sex. The findings aim to support evidence-based vaccine recommendations and enhance post-marketing surveillance [12,14]. While individual observational studies have reported these associations, a comprehensive synthesis quantifying pooled estimates across vaccine platforms and demographic subgroups remain necessary.

Materials and Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines. The review protocol was not prospectively registered.

Search strategy

A comprehensive literature search was conducted across databases like PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, Scopus and Web of Science. This search included studies published between December 2020 and March 2024. Search terms included combinations of COVID-19 vaccine, myocarditis, pericarditis, thromboembolism, vaccine safety, mRNA vaccine and viral vector vaccine.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria were peer reviewed studies, RCTs, cohort studies or case control studies; studies reporting sufficient data to calculate incidence and/or relative risk (event counts and denominators) of cardiovascular events following mRNA or Viral vector COVID-19 vaccines; adult populations (>18 years); and studies clearly mentioning the type of vaccine administered and cardiovascular outcomes assessed.

Exclusion criteria were case reports, case series, preprints, non-peer reviewed literature; studies lacking disaggregated data on vaccine type or cardiovascular outcomes; paediatric populations or studies without a comparator group.

Data extraction and quality assessment: For each included study, data on event counts and population denominators were extracted to calculate study-level incidence estimates and relative risks where applicable. Data extraction was performed independently by two reviewers using standardized data extraction forms. Extracted variables included study design, sample size, country, vaccine type, follow-up duration, incidence of myocarditis, pericarditis and thromboembolic events, and subgroup information stratified by age and sex. Any discrepancies between reviewers were resolved through discussion, and where required, consultation with a third reviewer.

Methodological quality of included studies was assessed using appropriate validated tools. Observational studies were evaluated using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale, assessing selection, comparability, and outcome domains. Randomized controlled trials were assessed for methodological rigor based on reported study design and outcome assessment. Studies were categorized as high or moderate quality based on overall scores.

Statistical analysis

Pooled incidence proportions of myocarditis, pericarditis, and thromboembolic events were estimated separately for mRNA and viral vector COVID-19 vaccines using a random-effects meta-analysis model to account for inter-study heterogeneity. Incidence estimates were calculated from study-level event counts and population denominators. Where sufficient comparative data were available within individual studies, relative risks with 95% confidence intervals were calculated at the study level and pooled using a random-effects model.

Between-study heterogeneity was assessed using Cochran’s Q test and quantified using the I² statistic, with I² values greater than 50% considered indicative of moderate to high heterogeneity. Subgroup analyses were conducted according to vaccine platform (mRNA vs. viral vector), age categories, and sex to explore potential sources of heterogeneity. Given variations in study design, surveillance systems, and outcome definitions, comparative risk estimates were interpreted cautiously.

Publication bias was assessed using funnel plots and statistically using Egger’s regression test when at least 10 studies were available for a given outcome. When fewer studies were available, formal assessment of publication bias was considered limited.

Forest plots were generated using study-level effect estimates (risk ratio or incidence rate ratio) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals as reported in individual studies. A random effect model was applied to account for between-study heterogeneity. Forest plots include only studies reporting comparable effect estimates with 95% confidence intervals; other included studies contributed to qualitative synthesis but not pooled quantitatively.

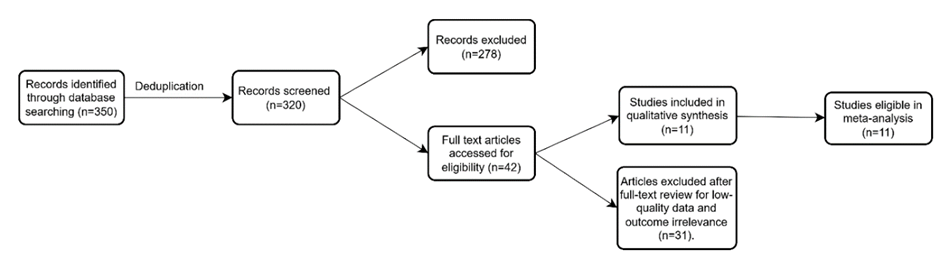

Study selection & characteristics: A total of 11 studies were included, encompassing a combined population of 58,620,611 participants who received COVID-19 vaccines. The included studies comprised large-population based cohort studies and randomized controlled trials conducted across multiple countries. These studies represented diverse demographic profiles and vaccination settings, enabling a comprehensive assessment of cardiovascular adverse events following COVID 19 vaccination across different populations. The study selection process is summarized in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1: PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for study selection.

Results

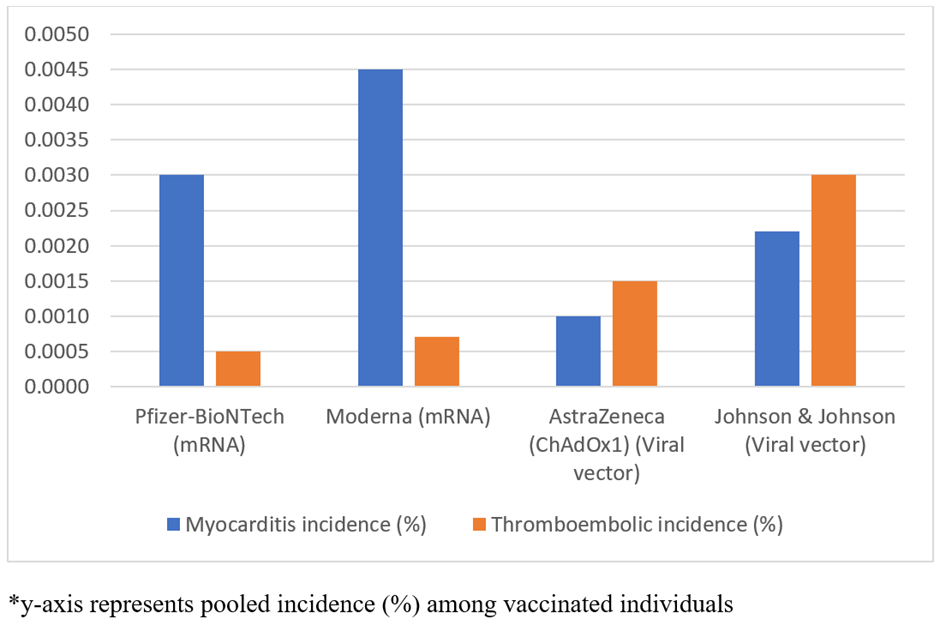

Vaccine type and cardiovascular adverse events: Figure 2 shows the pooled incidence of myocarditis and thromboembolic events according to COVID-19 vaccine platform. Among recipients of the Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccine, the pooled incidence of myocarditis was 0.003%, whereas thromboembolic events occurred in 0.0005% of vaccinated people. Similarly, among Moderna recipients, myocarditis incidence was higher (0.0045%), as compared with thromboembolic events i.e. 0.0007%.

Figure 2: Pooled incidence of cardiovascular adverse events by vaccine type.

In contrast, viral vector vaccines reported a lower pooled incidence of myocarditis, 0.0010% for AstraZeneca and 0.0022% for Johnson & Johnson. Overall these findings indicate differing cardiovascular adverse events across vaccine settings. With myocarditis occurring more frequently following mRNA vaccination and thromboembolic events occurring more frequently following viral vector vaccination.

Heterogeneity assessment: Substantial heterogeneity was observed across included studies. For myocarditis, Cochrane’s Q was 456.0 (df=3, p<0.001) with I2 99.3%, indicating considerable interstudy variation. Similarly, for thromboembolic events, Cochrane’s Q was 265.1 (df=3, p<0.001) and I2=98.9%. These findings justify use of random-effect model and further subgroup analysis were undertaken to find out potential sources of variability. The high heterogeneity may be due to differences in surveillance systems, risk windows, population age structures, and outcome definitions across studies.

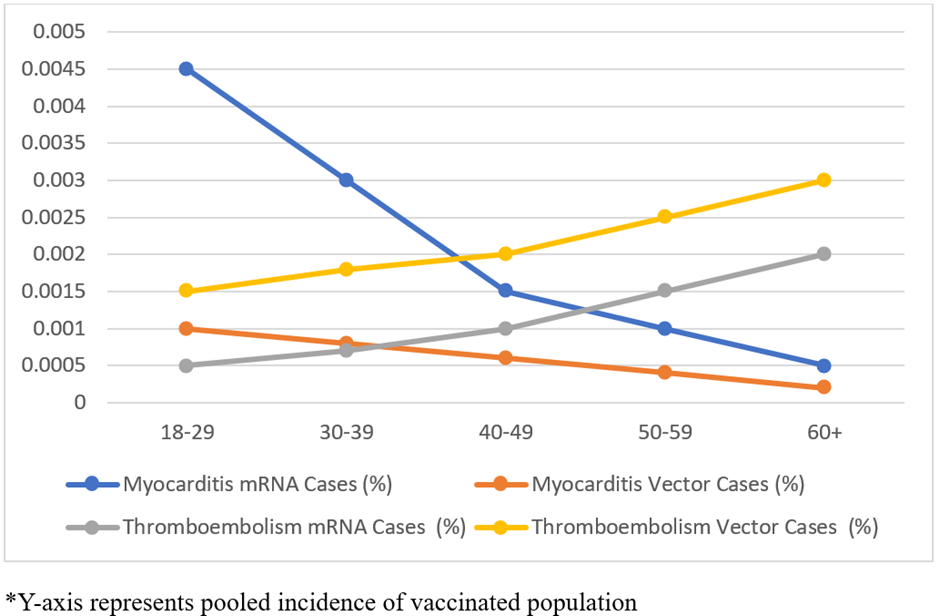

Association of cardiovascular adverse events with age and vaccine type: Age stratified pooled incidence estimates of myocarditis and thromboembolic events shown in Table 1 and Figure 3. Myocarditis incidence following mRNA vaccination was consistently higher across all age groups as compared with viral vector vaccines. The highest pooled incidence of myocarditis was reported in 18 – 29year age group (0.0045%) receiving mRNA vaccine, as compared to viral vector vaccines (0.001%).

|

Age group (Years) |

Estimated vaccinated population (pooled) |

Myocarditis (mRNA) Cases (%) |

Myocarditis (Viral-Vector) Cases (%) |

Thromboembolism (mRNA) Cases (%) |

Thromboembolism (Viral-Vector) Cases (%) |

|

18-29 |

14655153 |

659 (0.0045%) |

147 (0.0010%) |

73 (0.0005%) |

220 (0.0015%) |

|

30-39 |

11724122 |

352 (0.0030%) |

94 (0.0008%) |

82 (0.0007%) |

211 (0.0018%) |

|

40-49 |

10551710 |

158 (0.0015%) |

63 (0.0006%) |

106 (0.0010%) |

211 (0.0020%) |

|

50-59 |

9965504 |

100 (0.0010%) |

40 (0.0004%) |

149 (0.0015%) |

249 (0.0025%) |

|

60+ |

11724122 |

59 (0.0005%) |

23 (0.0002%) |

234 (0.0020%) |

352 (0.0030%) |

|

n = 58,620,611 |

|||||

|

*Percentages represent proportion of estimated vaccinated population within each age group. *Estimated vaccinated population derived from pooled national vaccination datasets across included studies. *Age-specific estimates represent pooled descriptive incidence proportions and were not used for comparative risk estimation. |

|||||

Table 1: Myocarditis & Thromboembolism by age group and vaccine type.

This pattern persisted across age group, 30 – 39 years showed 3.7-fold difference (0.0030% vs 0.0008%), and even among 60+ years, which is 2.5 times higher with mRNA vaccine (0.0005% vs 0.0002%).

In contrast, the pooled incidence of thromboembolic events increased progressively with advancing age for both vaccine types. Among mRNA vaccine recipient, thromboembolic incidence increased from 0.0005% in 18-29year age group to 0.0025% among 60 years and older. Similar age-related trend was observed for viral vector vaccines, with incidence increasing from 0.0015% to 0.003% across the same age categories. Across all age groups, thromboembolic events remained consistently higher following viral vector compared with mRNA vaccination (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Age-stratified pooled incidence of cardiovascular adverse events following COVID-19 vaccines.

Association of cardiovascular adverse events with sex and vaccine type: Sex stratified pooled incidence estimates are shown in Table 2. Among mRNA vaccine recipients, myocarditis incidence was markedly higher in males, with a pooled estimate of 106 cases per million (95% CI: 101.3 – 110.9), while among females it was 4.2 cases per million (95% CI: 3.35 -5.28). This sex-based difference was consistently observed across included studies.

|

Vaccine type |

Sex |

Myocarditis per million (95% CI) |

Thromboembolism per million (95% CI) |

|

mRNA |

Male |

106 (101.3–110.9) |

3.01 (2.30–3.94) |

|

Female |

4.21 (3.35–5.28) |

0.97 (0.60–1.55) |

|

|

Viral vector |

Male |

1.96 (1.31–2.94) |

9.98 (8.33–11.96) |

|

Female |

1.02 (0.59–1.79) |

8.96 (7.40–10.84) |

|

|

*Rates expressed per million vaccinated individuals *Sex-specific estimates are pooled across studies reporting sex-disaggregated data. |

|||

Table 2: Cardiovascular events vs sex and vaccine type.

For thromboembolic events, pooled incidence estimates were similar between males and females for both vaccine type. Among viral vector vaccine recipients, thromboembolic incidence was estimated at 9.98 per million in males (95% CI: 8.33-11.96) and 8.96 per million (95% CI: 7.40 – 10.84) in females. No consistent sex-based difference was observed for thromboembolic events.

Study quality assessment: Study quality was assessed using Newcastle-Ottawa Scale as shown in Table 3. Of the 11 included studies, 9 were rated high quality (score>8) and 2 were moderate quality (score 7). Most studies were large, population-based cohort studies or randomised controlled trials with good comparability and outcome assessment.

|

Study |

Design |

Selection (0-4) |

Comparability (0-2) |

Outcome (0-3) |

Total (0-9) |

Quality |

|

Mevorach et al. (2021) |

Cohort |

4 |

2 |

3 |

9 |

High |

|

Diaz et al. (2021) |

Retrospective cohort |

3 |

2 |

2 |

7 |

Moderate |

|

Witberg et al. (2021) |

Cohort |

4 |

2 |

3 |

9 |

High |

|

Husby et al. (2021) |

National Cohort |

4 |

2 |

3 |

9 |

High |

|

Klein et al. (2021) |

Surveillance Cohort |

3 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

High |

|

Patone et al. (2022) |

Cohort |

4 |

2 |

3 |

9 |

High |

|

Hippisley Cox et al. (2023) |

Cohort |

4 |

2 |

3 |

9 |

High |

|

Baden et al. (2021) |

RCT |

4 |

2 |

3 |

9 |

High |

|

Voysey et al. (2021) |

RCT |

4 |

2 |

3 |

9 |

High |

|

Polack et al. (2020) |

RCT |

4 |

2 |

3 |

9 |

High |

|

Li et al. (2022) |

Multi-database study |

3 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

High |

|

*Observational studies were assessed using Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS). Randomized controlled trials were assessed using adapted NOS domains to ensure consistency across study designs. |

||||||

Table 3: Study quality assessment.

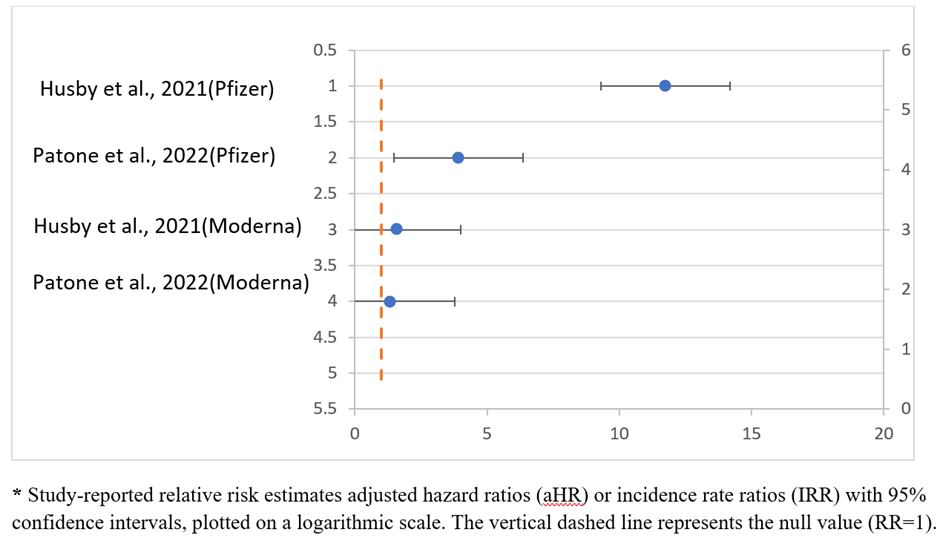

Forest plots analyses show an increased risk of myocarditis following mRNA COVID-19 vaccination, particularly with mRNA-1273 (Moderna), compared with other vaccine types (Figure 4). The pooled estimates across population-based cohort studies showed a consistent direction of effect, with substantial between study heterogeneity reflecting difference in age distribution, risk windows, and surveillance systems.

Figure 4: Forest plot 1: Myocarditis risk following mRNA COVID-19 vaccination (0-28 days) study.

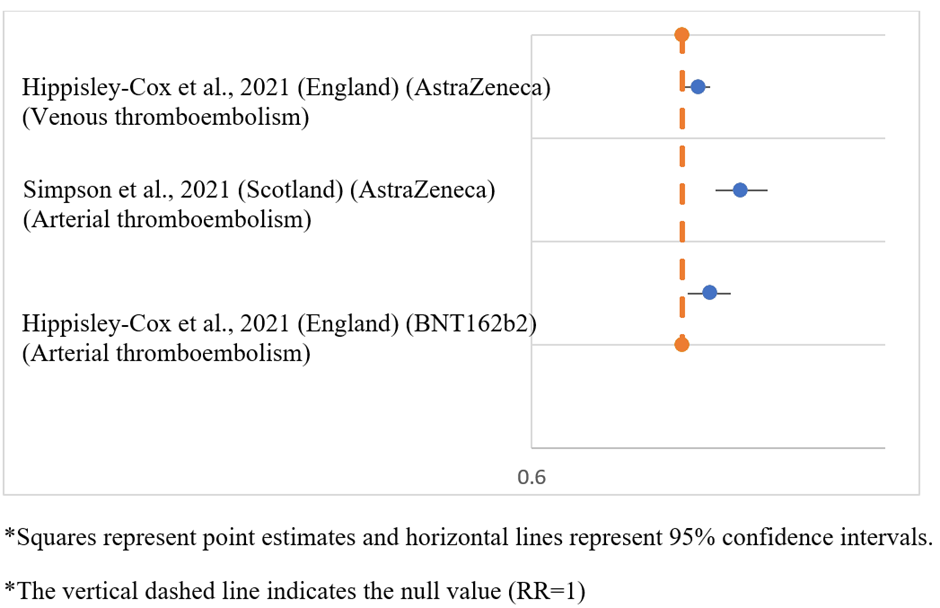

Thromboembolic outcomes showed a modestly higher risk following viral vector vaccines, specially ChAdOx1 (AstraZeneca), compared with mRNA vaccines (Figure 5). Although the absolute risk remained low, the association was consistent across large cohort studies, with moderate to high heterogeneity.

Figure 5: Forest plot of thromboembolic events following COVID-19 vaccination.

Discussions

This meta-analysis brings together evidence from large population-based studies and RCT to evaluate cardiovascular adverse events following COVID-19 vaccination across different vaccine platforms. The findings indicate that myocarditis occurs more frequently following mRNA vaccination, particularly with Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines, whereas thromboembolic events were more commonly observed following viral vector vaccines, especially AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson. Importantly, the absolute incidence of these adverse events remained low across all vaccine types.

The higher pooled incidence of myocarditis following mRNA vaccination, especially among younger males, is consistent with previously published studies. Large cohort studies by Mevorach et al. [1], Witberg et al. [3], and Husby et al. [4] observed increased myocarditis incidence after mRNA vaccination, with a higher occurrence after Moderna compared with Pfizer-BioNtech. This pattern has been attributed likely to the difference in vaccine formulations and antigen dose, with Moderna containing a higher mRNA content. Observational study by Diaz et al. [2] and Klein et al. [5] further confirmed these patterns, reporting rare but more frequent myocarditis in younger male’s post-mRNA vaccination. Li et al. [11] emphasized this age and sex-specific risk, with potential mechanisms involving testosterone-driven immune responses and molecular mimicry between SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and cardiac antigens [19].

On the contrary, current study shows thromboembolism is more commonly associated with viral vector vaccines, which align with report by Hippisley-Cox et al. [7], who found increased risk of venous thromboembolism and CVST after ChAdOx1 vaccination. The underlying mechanism most likely involves anti PF4 antibody mediated platelet activation, similar to heparin induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) [18].

Although these adverse events are concerning, the overall incidence of cardiovascular adverse events following vaccination was substantially lower than incidence reported following SARS-CoV-2 infection. Patone, et al., Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the WHO, have shown increased rates of myocarditis, pericarditis and thromboembolism following SARS-CoV-2 infection, reinforcing the favorable risk-benefit profile of vaccination [6,14]. Variability across studies may be due to differences in case definition, diagnostic criteria, demographics, surveillance systems. However, the consistency of signals across diverse settings lends strength to these associations and highlights the need for risk stratification and individualized vaccine recommendations [20].

The analysis further shows a significantly higher myocarditis risks in males under 30, consistent with Mevorach et al. (90% male), Witberg et al (10.7 per 100,000 in males vs 0.7 in female) [1,3] and supported by US based CDC data (Oster et al.) [15]. These findings point to hormonal influence, with testosterone amplifying pro-inflammatory responses and oestrogen giving potential protection [19]. In contrast, pooled estimates for thromboembolic events did not demonstrate a consistent or statistically significant difference between males and females across vaccine types.

Reports by Hippisley-Cox et al., EMA 2021 have noted higher thromboembolism rates in younger female after AstraZeneca vaccination [7,13], while the pooled analysis did not show a significant sex difference. This could be attributed to the broad age range in the data or inclusion of thromboembolic events beyond confirmed VITT cases, diluting the signal. Buchan et al. further emphasized that myocarditis rates vary by vaccine product, schedule and interval, particularly in Canadian cohorts [16]. Moreover, when compared globally, the findings are consistent with meta-analysis conducted by Chou et al. [17].

Overall, this meta-analysis highlights distinct but rare cardiovascular adverse event profiles associated with different COVID-19 vaccine types. The findings underscore the importance of continued post marketing surveillance, standardized case definitions, age and sex stratified safety monitoring to inform public health decision making while maintaining confidence in vaccination programs.

Conclusion

The meta-analysis shows higher incidence of myocarditis following mRNA COVID-19 vaccines and relatively increased thromboembolic events with viral vector vaccines. Although, these adverse events remain rare, the findings are consistent with international data and biologically plausible mechanisms. Myocarditis was significantly more frequent among males, especially younger individuals, whereas thromboembolic events were observed slightly more in females following viral vector vaccines, though it is statistically not significant. Importantly, the overall risk of these cardiovascular events remains substantially lower than the risk associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection itself.

The study shows caution may be warranted when considering mRNA vaccines in individuals under 30 years, particularly dosing interval. Wherever feasible alternative vaccine platform such as protein subunits or inactivated vaccines may be considered for high-risk groups. Vaccine safety surveillance system should continue to disaggregate data by sex and age to enhance early detection of rare adverse events. The use of standardised definitions for myocarditis and thromboembolism is essential for accurate reporting and meaningful comparison across studies. Healthcare provider should provide clear, evidence-based information on vaccine risks and benefits, especially for young males receiving mRNA vaccine and younger female receiving viral vector vaccines. More prospective research needs to explore the mechanism behind sex-based difference in adverse event and to assess long term cardiovascular outcomes. Based on emerging evidence, regulatory bodies should consider updating vaccine recommendations, booster policies.

This meta-analysis has several limitations. First, moderate to high heterogeneity in the study design, population and outcome definitions, may have influenced the pooled estimates. Reporting bias is possible, as many included studies relied on passive surveillance systems, which are prone to under reporting and differential reporting by sex and age. Additionally, publication bias cannot be excluded, as studies with significant findings are more likely to be published. There is also variability in case definitions for myocarditis and thromboembolism, potentially affecting comparability. The analysis was based on aggregate data, limiting the ability to adjust for individual-level confounders such as comorbidities, prior infection, vaccine dosing interval. Furthermore, long-term outcomes of these adverse events were not consistently reported, restricting conclusions on prognosis and recovery. In addition, publication bias could not be evaluated because small number of studies included in the quantitative analyses. Despite these limitations, the large sample size and consistency of trends across multiple countries strengthen the validity of the findings.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that there are no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Funding: This research received no external funding.

Ethical Guideline: This study is a systematic review and meta-analysis based on previously published literature and publicly available data. It did not involve human participants, patient data, or animal subjects. Therefore, ethical approval from an institutional ethical committee was not required.

References

- Mevorach D, Anis E, Cedar N, Bromberg M, Haas EJ, et al. (2021) Myocarditis after BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine against COVID-19 in Israel. N Engl J Med 385: 2140-2149.

- Diaz GA, Parsons GT, Gering SK, Meier AR, Hutchinson IV, et al. (2021) Myocarditis and pericarditis after vaccination for COVID-19. JAMA 326: 1210-1212.

- Witberg G, Barda N, Hoss S, Richter I, Wiessman M, et al. (2021) Myocarditis after COVID-19 vaccination in a large health care organization. N Engl J Med 385: 2132-2139.

- Husby A, Hansen JV, Fosbøl E, Thiesson EM, Madsen M, et al. (2021) SARS-CoV-2 vaccination and myocarditis or myopericarditis: A nationwide cohort study. BMJ 375: e068665.

- Klein NP, Lewis N, Goddard K, Fireman B, Zerbo O, et al. (2023) Surveillance for adverse events after COVID-19 mRNA vaccination. JAMA 329: 257-265.

- Patone M, Mei XW, Handunnetthi L, Dixon S, Zaccardi F, et al. (2022) Risks of myocarditis, pericarditis, and cardiac arrhythmias associated with COVID-19 vaccination or SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med 28: 410-422.

- Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland CA, Mehta N, et al. (2023) Risk of thromboembolic events after COVID-19 vaccination: A UK cohort study. BMJ 380: e072456.

- Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, Kotloff K, Frey S, et al. (2021) Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med 384: 403-416.

- Voysey M, Clemens SAC, Madhi SA, Weckx LY, Folegatti PM, et al. (2021) Safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2. Lancet 397: 99-111.

- Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, et al. (2020) Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med 383: 2603-2615.

- Li X, Ostropolets A, Makadia R, et al. (2022) Characterizing the incidence of myocarditis across age and sex following COVID-19 vaccination. JAMA Cardiol 7: 626-636.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2023) Myocarditis and pericarditis following mRNA COVID-19 vaccination.

- European Medicines Agency (2023) Pharmacovigilance risk assessment of COVID-19 vaccines.

- World Health Organization (2023) COVID-19 vaccines: Safety surveillance manual.

- Oster ME, Shay DK, Su JR, Gee J, Creech CB, et al. (2022) Myocarditis cases reported after mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccination in the US from December 2020 to August 2021. JAMA 327: 331-340.

- Buchan SA, Seo CY, Johnson C, Alley S, kwong JC, et al. (2022) Epidemiology of myocarditis and pericarditis following mRNA vaccines in Ontario, Canada. Vaccine 40: 2595-2603.

- Chou OHI, Zhou J, Lee TT, et al. (2023) Global epidemiology of vaccine-associated myocarditis and pericarditis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect 29: 18-27.

- See I, Su JR, Lale A, Woo EJ, Guh AY, et al. (2021) US Case Reports of Cerebral Venous Sinus Thrombosis With Thrombocytopenia After Ad26.COV2.S Vaccination, March 2 to April 21, 2021. JAMA 325: 2448-2456.

- Bozkurt B, Kamat I, Hotez PJ (2021) Myocarditis with COVID-19 mRNA vaccines. Circulation 144: 471-484.

- Boehmer TK, Kompaniyets L, Lavery AM, Hsu J, Ko JY, et al. (2021) Association between COVID-19 and myocarditis using hospital-based administrative data—United States, March 2020–January 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 70: 1228-1232.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.