Breast Cancer in Eastern Sudan: Clinicopathological Predictors of Prognosis: A Comparative Analysis Between Kassala and Gadarif Oncology Centers

by Sami Eldirdiri Elgaili*, Elssayed Osman Elssayed, Mohammed Hassan Ibrahim

Department of General Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, University of Gadarif, Al Qadarif, Sudan

*Corresponding author: Sami Eldirdiri, Department of General Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, University of Gadarif, Al Qadarif, Sudan

Received Date: 21 November 2025

Accepted Date: 02 December 2025

Published Date: 04 December 2025

Citation: Elgaili SE, Elssayed EO, Ibrahim MH (2025) Breast Cancer in Eastern Sudan: Clinicopathological Predictors of Prognosis: A Comparative Analysis Between Kassala and Gadarif Oncology Centers. J Surg 10:11502 https://doi.org/10.29011/2575-9760.011502

Abstract

Background: Breast cancer is the most common malignancy among Sudanese women and is frequently diagnosed at advanced stages. Despite increasing incidence, data from Eastern Sudan remain limited.

Objectives: To compare the clinicopathological features and prognostic determinants of breast cancer among patients treated at Kassala and Gadarif Teaching Hospitals in Eastern Sudan.

Methods: A hospital-based comparative descriptive-analytic study was conducted from January to December 2024. Demographic, clinical, and histopathological characteristics were analyzed. Prognosis was evaluated using tumor size, histologic grade, and lymph node involvement based on the Nottingham index.

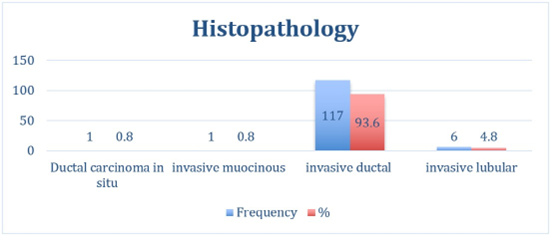

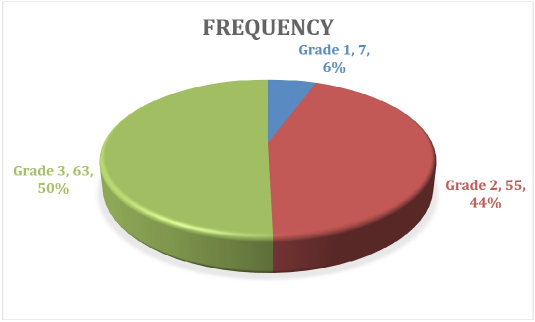

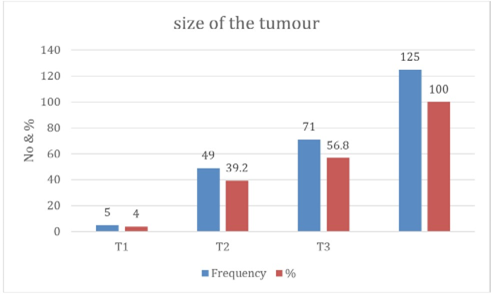

Results: Among the 125 patients with breast cancer who were included in the study, the mean age was 48.5 ± 11.9 years; 95.8% were female. Invasive ductal carcinoma was predominant (93.6%). Concerning the histopathology, half of all tumors were grade 3, and 56.8% were >5 cm (T3). A total of 40.8% had >3 metastatic lymph nodes. Kassala had significantly larger tumors compared to Gadarif (p = 0.006). Most patients had poor prognostic scores (57.6%). Prognosis differed significantly between centers (p = 0.015).

Conclusion: Breast cancer in Eastern Sudan affects relatively young women and presents with aggressive features and advanced stages. Significant regional disparities exist between Kassala and Gadarif. Routine screening programs, community awareness campaigns, and improved pathology capacity are critical to reducing late presentation

Keywords: Breast Cancer; Eastern Sudan; Gadarif; Grade; Kassala; Lymph Nodes; Prognosis; Stage

Introduction

Breast cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related morbidity and mortality among women in Sudan [1]. Over the past two decades, its burden has steadily increased, reflecting an actual rise in incidence and improvements in hospital-based reporting. In resource-limited settings such as Eastern Sudan, the pattern of disease presentation and biological behavior diverges from global trends, with younger age at onset and a predominance of advanced stages at diagnosis [2]. In Sudan, disparities in healthcare infrastructure and diagnostic capacity contribute to delayed detection. Most patients seek medical care only after the disease becomes locally advanced or metastatic [3]. Histopathological studies from Khartoum and other northern regions have shown that invasive ductal carcinoma is the predominant subtype, frequently of high histologic grade [4]. However, few published data exist from Eastern Sudan—particularly Kassala and Gadarif-where diagnostic and oncologic services have only recently expanded. Living in rural areas with low educational levels was the second most common cause contributing to delayed diagnosis and advanced stages of the disease presentations in many women in Sudan [5]. Another study found that the use of traditional methods, fear of diagnosis, and low awareness of breast self-examination contributed to advanced disease presentation [6]. No study has directly compared the clinicopathological features between Kassala and Gadarif, the two major regional oncology centers with differing healthcare resources.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Setting

This was a comparative, hospital-based descriptive and analytical study conducted at two major oncology centers in Eastern Sudan: Kassala Teaching Hospital (Kassala State) and Gadarif Teaching Hospital (Gadarif State). Both institutions serve as regional referral centers for surgical and oncologic management of breast cancer and receive patients from neighboring states and rural areas. The study period ran from January to December 2024. ER, PR, and HER2 receptors were missing or unavailable in most of the cases so the receptor status was removed

Study Population

The study included all female patients with histologically confirmed primary breast carcinoma who presented to either of the two hospitals during the study period.

Inclusion Criteria

- Patients with a core or incisional biopsy confirmed diagnosis of invasive breast carcinoma based on histopathology.

- Patients who completed initial surgical and/or oncologic evaluation at either Kassala or Gadarif centers.

- Availability of complete histopathological parameters (grade, size of the tumor, and number of lymph nodes involved)

- Patients with recurrent breast cancer or previous malignancies.

- Patients with incomplete medical or histopathological records.

Exclusion Criteria

Data Collection: Data were extracted prospectively from hospital oncology registries, surgical logbooks, and pathology reports. A structured checklist was used to record demographic data (age, sex, residence), clinical presentation (tumor size, palpable nodes, stage), and histopathology (tumor type, grade, lymph node status).

Data Analysis: Data were analyzed using SPSS version 26 and Excel (Table 1) (Figure 1).

|

Variables |

N |

% |

|

|

Sex |

Female |

125 |

95.8 |

|

Male |

6 |

4.2 |

|

|

Age: (N=125) |

20 – 30 |

9 |

7.2 |

|

31 - 40 |

29 |

23.2 |

|

|

41 - 50 |

39 |

31.2 |

|

|

51- 60 |

29 |

23.2 |

|

|

>60 |

19 |

15.2 |

Table 1: Demographic (age + sex) & BMI in the study.

Figure 1: Histopathology.

Discussion

This study examined the demographic and pathological characteristics of 125 Sudanese patients with breast cancer who were treated at two major centers in Eastern Sudan: El Gadarif and Kassala. The findings reveal significant differences in patient age, tumor size, grade, and prognosis between the two centers, underscoring important regional disparities in disease presentation and burden. The mean patient age was 48.5 ± 11.9 years, consistent with previous Sudanese studies that reported a younger median age of onset, approximately a decade earlier than in high-income countries [2,7]. Most patients were middle-aged (35-54 years), suggesting a regional trend toward earlier disease onset, likely driven by genetic, reproductive, and environmental factors. This earlier onset may suggest a more aggressive disease or limited screening options. In Kassala, patients were slightly older on average, with more in the 45-64 age range, possibly indicating delayed presentation or differing population structures. Similar age patterns have been noted in studies from Ethiopia and Egypt, where breast cancer commonly affects women in their forties and early fifties [8,9]. The study revealed a notable prevalence of large tumors: 56.8% exceeded 5 cm (T3), and only 4% were smaller than 2 cm. This suggests a trend of late presentations and limited access to screening. Notably, Kassala had a higher number of large tumors (40 cases) compared to El Gadarif (21 cases), indicating more advanced disease at diagnosis. This difference is statistically significant (p < 0.05) and may reflect lower community awareness or diagnostic delays. These findings align with previous reports from Khartoum and Wad Madani, where over half of patients presented with stage III or IV disease [10,11]. Insufficient early detection services and sociocultural barriers, like stigma and reliance on traditional remedies, contribute to late diagnoses in Sudan and neighboring countries [12].

Invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) constituted 93.6% of all cases, a proportion comparable to global estimates but slightly higher than regional averages [13,14]. Other studies from Nigeria and Kenya report slight histologic variation: 68.1% and 84.3%, respectively [15,16]. Poorly differentiated (grade 3) tumors made up half of the cases, with Kassala reporting 36 cases compared to 27 in Elgadarif. There was no statistically significant difference in tumor grade distribution between the two centers (p > 0.05) (Table 2). This suggests a trend toward more aggressive pathology in Eastern Sudan, compared with with findings from Tanzania , which show report a predominance of grade 2 account about 74.8 % [17], and study from Egypt show more advanced stage and aggressive biological subtypes compared with Western and other developed countries [18]. Most breast cancer patients have 0 to 3 positive lymph nodes, while four or more indicate a higher risk. Patients with 10 or more metastatic nodes face the poorest prognosis due to greater disease burden and a higher chance of distant metastasis [19-22]. In our study, more than 40% of patients had more than three lymph nodes involved, consistent with the literature and confirming the advanced disease burden at presentation. There is no significant association between the treating center and lymph node involvement category (P = 0.401), indicating similar distributions of node involvement (0, 1–3, >3) between the two centers (see Table 2, Figures 2,3). Most patients in this Eastern Sudan cohort presented with axillary lymph node-positive disease, and many had high-burden nodal metastasis (4 or more nodes). This reflects the documented late presentation of breast cancer in Sudan, where delays in consultation and treatment lead to more advanced stages at diagnosis [5,6]. Recent Sudanese series similarly report a predominance of node-positive disease, reflecting limited screening programs and barriers to early detection in resourceconstrained settings [23,24]. Globally, lymph node involvement is a crucial prognostic factor in breast cancer and informs decisions regarding adjuvant systemic therapy and radiotherapy [25,26]. The observed distribution aligns with international data showing that patients with four or more positive nodes are a high-risk group needing more aggressive treatment [27-29]. The similar nodal burden between Kassala and El-Gadarif suggests consistent disease patterns and healthcare access in the region. This emphasizes the need to improve breast cancer screening, early referrals, and treatment pathways in low-resource areas like Sudan to enhance early detection and survival rates.

Study variables | Treating center | ||||

Kassala | Elgadarif | ||||

No | % | No | % | ||

Size of the Tumor | ≤2 cm (T1) | 1 | 1.4 | 4 | 7.8 |

Chi-square = 10.134, p = 0.0063 | 2–5 cm (T2) | 23 | 31.1 | 25 | 49 |

>5 cm (T3) | 50 | 67.5 | 22 | 43.2 | |

Total | 74 | 100 | 51 | 100 | |

Number of LN involved: | No lymph nodes | 19 | 25.7 | 19 | 37.3 |

1–3 nodes | 25 | 33.8 | 11 | 21.6 | |

Chi-square = 2.899, p = 0.2347 | 4–9 nodes | 18 | 24.3 | 12 | 23.5 |

≥10 nodes | 12 | 16.2 | 9 | 17 | |

Total | 74 | 100 | 51 | 100 | |

Grade of the Tumor | |||||

Chi-square statistic: 2.171 | Grade 2 | 32 | 43.3 | 23 | 45.1 |

Grade 3 | 36 | 48.6 | 27 | 52.9 | |

P-value: 0.3377 | Total | 74 | 100 | 51 | 100 |

Prognosis | Good | 2 | 2.7 | 2 | 3.9 |

Moderate | 21 | 28.4 | 27 | 52.9 | |

(Chi-square for prognosis: p = 0.0156) | Poor | 51 | 68.9 | 22 | 43.1 |

Total | 74 | 100 | 51 | 100 | |

Table 2: Cross tabulation between two Centers, grade of the tumor, LN involvement, and size of the tumor.

Figure 2: The grade of the Tumor.

Figure 3: The size of the Tumor.

The strong correlation between tumor grade, size, and nodal status aligns with established prognostic models such as the Nottingham system and TNM staging 5. Globally, breast cancer prognosis varies markedly across regions, reflecting inequities in early detection, tumor biology, and access to multimodality treatment. In high-income countries, 5-year survival commonly exceeds 85–90% owing to widespread screening, timely diagnosis, and the availability of targeted systemic therapies [30-32] . In contrast, many low- and middle-income countries report 5-year survival rates below 50%, largely due to late-stage presentation, limited access to pathology and imaging, and constrained radiotherapy and chemotherapy resources [33,34]. The prognosis in our study was poor, with 58.4% of patients affected by biological aggressiveness and systemic management delays. Kassala’s larger tumor size and higher grade 3 frequency likely worsen its prognosis compared to El Gadarif. These differences may stem from Lower screening rates, Delayed diagnosis, Inconsistent access to pathology, radiotherapy, and targeted therapy. Improving regional capacity in oncology diagnostics, early detection, multidisciplinary treatment planning and address systemic barriers to care in resource-limited settings is essential to address these gaps. Finaly, there is high need for public health implications such as dedicated breast units, access to mammography service and screening programs, raising the community awareness and earlier referral pathway.

Conclusion

Breast cancer in Eastern Sudan affects relatively young women and presents with aggressive features and advanced stages. Significant regional disparities exist between Kassala and Gadarif. Routine screening programs, community awareness campaigns, and improved pathology capacity are critical to reducing late presentation

Strength and limitations: The first comparative study but lacks molecular subtyping, survival outcomes being a hospital-based sampling.

Conflict of interest: No Conflict of interest.

Ethical approval: Approval was obtained from the participating hospitals.

Acknowledgement: The authors express gratitude to the surgical and pathology teams at Gadarif and Kassala Teaching Hospitals for their cooperation and support during data collection and patient follow-up. We also thank the hospital administration and ethical review committees for their permission to conduct this study, as well as the patients and their families for their participation. Lastly, we appreciate the contributions of colleagues and research coordinators in data entry, statistical analysis, and manuscript preparation.

References

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL (2024) Global Cancer Statistics 2024: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 74: 153-178.

- Elzaki A, Elhassan A, Ali H (2023) Patterns of Breast Cancer Presentation and Management in Eastern Sudan. Sudan J Med Sci 18: 22-30.

- Ahmed T, Elhadi M, Salih AM (2024) Delays in Breast Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment in Sudan: A Multicenter Analysis. BMC Cancer 24: 1052.

- Hassan HA, Abdallah TM, Babiker AM (2022) Histopathological Patterns of Breast Cancer in Sudanese Women: A Hospital-Based Review. Afr J Med Health Sci 21: 115-121.

- Alfadul ESA, Tebaig B, Alrawa SS, Elgadi AT, Margani EEMA, et al. (2024) Delays in presentation, diagnosis, and treatment in Sudanese women with breast cancer: a cross-sectional study. The Oncologist 29: e771-e778.

- Elamin HES, Elamin HES, El-Raheem GOHA, Noma M (2025) Barriers to Early Breast Cancer Diagnosis in Sudanese Women Before the War. Breast Cancer 17: 433-445.

- Hassan HA (2020) Determinants of lymph node yield after axillary dissection in breast cancer patients. Egypt J Surg 39: 1102-1110.

- Ahmed M (2024) Breast cancer characteristics and outcomes in northern Ethiopia. BMC Women’s Health 24: 88.

- El-Sayed ME (2023) Clinicopathological features of breast cancer in Egyptian women: a multicenter analysis. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst 35: 31.

- Mohamed NMI (2025) The yield of axillary clearance in breast cancer in Khartoum. Ann Med Surg 81: 105302.

- Saeed AM (2023) Stage at diagnosis and treatment outcomes of breast cancer in Wad Medani Teaching Hospital. East Afr Med J 100: 95-101.

- Gailani S (2024) Barriers to breast cancer screening in low-resource settings. J Glob Oncol 10: e2200456.

- Belachew EB, Desta AF, Deneke DB (2023) Clinicopathological Features of Invasive Breast Cancer: A Five-Year Retrospective Study in Southern and South-Western Ethiopia. Journals Medicines 10: 30.

- Abd-Rabh RM, Agina HA, Mohamed AG, Bassyoni OY (2025) A Comprehensive Study of Invasive Breast Cancer in Egyptians: Histological Subtypes and Prognostic Indicators. The Egyptian Journal of Hospital Medicine 101: 4588-4594.

- Omeaku AMG, Oparaocha ET, Nweke IG, Ebirim CIC, Nwokorie J, et al. (2024) Morphological Subtypes of Breast Cancer Among Women of Childbearing Age in Imo State, Nigeria. Int.J.Curr.Microbiol.App.Sci 13: 199-203.

- Wanjara S, Mithe S, Osoo MO (2024) Molecular Subtypes of Receptordefined Breast Cancer from Nakuru, Kenya. East Cent Afr J Surg 29: 35-41.

- Ismail A, Panjwani S, Ismail N, Ngimba C, Mosha I, et al. (2024) Breast cancer molecular subtype classification according to immunohistochemistry markers and its association with pathological characteristics among women attending tertiary hospitals in Tanzania.heliyon 10: e38493.

- Azim HA (2023) Clinicopathologic features of breast cancer in Egypt. Clinicopathologic Features of Breast Cancer in Egypt— A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JCO Glob Oncol 9: e2200387.

- Mousavi-kiasary SMS, Bayat M, Abbasvandi F (2025) Tumor characteristics and survival rate of axillary metastatic breast cancer patients: a three decades retrospective cohort study. Sci Rep 15: 4571.

- Eliyatkın NO, Başkır I, İşlek A, Zengel B (2023) New Lymph Node Parameters and a Comparison with the American Joint Committee on Cancer N-Stages in Breast Cancer. Cyprus J Med Sci 8: 276-286.

- Kenny R (2022) Can one-step nucleic acid amplification assay predict four or more positive axillary lymph node involvement in breast cancer patients: a single-centre retrospective study. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 104: 216-220.

- Comparing lymph-node metrics (pN categories incl. ). ESMO Open 7: 100635.

- Ahmed ABM (2024) Breast cancer in Eastern Sudan: retrospective hospital-based analysis. Ecancer medical science 18: 1704.

- Muddather HF, Elhassan MM, Faggad A (2021) 0Survival outcomes of breast cancer in Sudanese women. JCO Glob Oncol 7: 324-332.

- Balic M (2023) St. Gallen/Vienna 2023 international consensus on breast cancer treatment. Breast Care 18: 213-222.

- Taylor C (2023) Regional nodal irradiation in early breast cancer. Lancet 401: 1943-1956.

- Gnant M (2021) Adjuvant therapy in high-risk node-positive breast cancer. Lancet 397: 1815-1820.

- Lammers SWM, Meegdes M, Vriens IJH, Voogd AC, de Munck L, et al. (2024) Treatment and survival of patients diagnosed with high-risk HR+/HER2− breast cancer in the Netherlands: a population-based retrospective cohort study. ESMO Open 9: 103008.

- Kay C, Martinez-Perez C, Michael Dixon J, Turnbull AK (2023) The Role of Nodes and Nodal Assessment in Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prediction in ER+, Node-Positive Breast Cancer. J.Pers.Med 13: 1476.

- Giaquinto AN, Sung H, Newman LA, Freedman RA, Smith RA, et al. (2024) Breast cancer statistics: 2024. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 74: 477-495.

- Cserni G, Chmielik E, Sejben I (2020) Stage-specific survival in breast cancer: an updated international comparison. Eur J Cancer 137: 5058.

- Bray F, Laversanne M, Weiderpass E, Soerjomataram I (2021) The ever-increasing importance of cancer as a leading cause of premature death worldwide. Cancer 127: 3029-3030.

- McCormack V, McKenzie F, Foerster M, Zietsman A, Galukande M, et al. (2020) Breast cancer survival and survival gap apportionment in sub-Saharan Africa (ABC-DO): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Glob Health 8: e1203-e1212.

- Azamjah N, Soltan-Zadeh Y, Zayeri F (2019) Global Trend of Breast Cancer Mortality Rate: A 25-Year Study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 20: 2015-2020.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.