BRAFV600E Mutation Status in Children and Adolescents with Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis-A Retroprospective Study from A Greek Reference Center

by Haroula Tsipou1*, Efthymia Rigatou1, Stavros Glentis1, Kalliopi Stefanaki2, Antonis Kattamis1

1Division of Pediatric Hematology-Oncology, First Department of Pediatrics, "Aghia Sophia" Children's Hospital, Full Member of ERN GENTURIS and ERN EUROBLOODNET, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece.

2Department of Pathology, "Aghia Sophia" Children's Hospital, Athens, Greece.

*Corresponding author: Tsipou H, Division of Pediatric Hematology-Oncology, First Department of Pediatrics, "Aghia Sophia" Children's Hospital, Full Member of ERN GENTURIS and ERN EUROBLOODNET, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece.

Received Date: 30 January, 2026

Accepted Date: 06 February, 2026

Published Date: 09 February, 2026

Citation: Tsipou H, Rigatou E, Glentis S, Stefanaki K, Kattamis A (2026) BRAFV600E Mutation Status in Children and Adolescents with Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis-A Retroprospective Study from A Greek Reference Center. J Oncol Res Ther 11: 10330. https://doi.org/10.29011/2574-710X.10330

Abstract

Background: Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare myeloid neoplastic disorder driven by mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) activation in hematopoietic cells. The understanding of pathogenesis has been greatly advanced by the detection of BRAFV600E mutations in over 50% of LCH lesions. The aim of the present study is to describe demographic data, clinical characteristics and therapeutic outcome in cases of children with Langerhans Histiocytosis with or without BRAFV600E mutation. Methods: A retrospective analysis of children with LCH treated at a reference center in Greece from 2012 to 2024 was performed. Results: Twenty-eight children were diagnosed with LCH with 57.14% of them showing positivity for the BRAFV600E mutation. Age less than 3 years, higher LDH levels at diagnosis were marginally associated with the presence of the BRAF mutation. The BRAF positive status was reported in all multi-system cases. The 5-year event-free survival (EFS) was found 80.0%, 91.7% and 74.1% for negative, positive and unknown BRAF status, respectively with no statistically significant differences. Conclusions: Children with LCH have a high overall and eFS, while BRAFV600E mutation may be associated with more aggressive features.

Keywords: LCH; BRAFV600E; Mutation Status; Children.

Abbreviations

ccf-DNA :Circulating Cell-Free DNA,

CNS: Central Nervous System,

CR :Complete Remission,

EFS :Event-Free Survival,

LCH :Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis,

ERK :Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase,

MAPK : Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase,

MF: Multifocal, MS: Multi-System,

SS: Single System,

OS : Overall Survival,

RT-PCR: Real Time Polymerase Chain Reaction,

RO-: No Risk Organ Involvement,

RO+ : Risk Organ Involvement,

UF: Unifocal

Introduction

LCH is a rare hematological disorder that occurs prevalently in children. The incidence ranges from 2.6 to 8.9 cases per million children younger than 15 per year, with a median age at diagnosis of 3 years old [1] and 1 per million children in children older than 15 years of age[2].

Diagnosis of LCH requires a clonal neoplastic proliferation with expression of CD1a, CD207 (Langerin) and S100. The cells are generally large, round to oval, with a coffee-bean nuclear grove and without the branching that characterizes inflammatory CD1a1 dendritic cells. On electron microscopy, pentalaminar cytoplasmic rod-shaped inclusions named Birbeck granules can be identified. In the presence of CD2071 staining, electron microscopy is no longer required for diagnosis [3]. Since almost any organ can be infiltrated by LCH cells, symptomatology is dependent on the extent of the disease [4]. Based on the number of organs or systems involved, LCH can be classified into single-system (SS-LCH) and multi-system (MS-LCH) with or without risk organ involvement (RO+/RO-) [2]. The single system LCH can be at single site (unifocal-UF) or multiple sites (multifocal-MF). In addition, patients with isolated lesion in one of the craniofacial bone are characterized as central nervous system (CNS)-risk lesions and required systemic chemotherapy [5]. The systems that are more affected in children are the bones (80%), skin (33%), the pituitary gland (25%), liver, spleen, hematopoietic system (15% each), lymph nodes (5%-10%) or CNS (2%-4% excluding the pituitary) [2].

Presenting features of LCH are extremely variable. The most frequent are palpable mass, bone pain or fracture, eczema, lymphadenopathy, polyuria and polydipsia due to diabetes insipidus [6].

A breakthrough in understanding LCH pathogenesis came with the discovery of recurrent BRAFV600E mutations in over 50% of LCH lesions [5]. The presence of the BRAF mutation encoding the V600E (Val600Glu) variant in LCH was first reported in 2010 [6]. BRAF is a central kinase of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway which regulates critical cellular functions The BRAFV600E mutation encodes a cytoplasmic mutant protein with constitutive activation, which confers independence from upstream activation by one of the RAS proteins. The BRAFV600E mutation induces constitutive activation of downstream MAPK/ERK kinase and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) proteins [7]. Apart for BRAFV600E mutation, other recurrent somatic mutations in the MAPKinase pathway like MAP2K1, MAP3K1, PIK3CA and FAM73A-BRAF have been identified [8, 9].

After initial screening tests, minimal therapy (symptomatic treatment, local therapy, and/or a wait-and-see strategy) without systemic chemotherapy is the recommended option for many patients (45%). Other patients benefit from first-line chemotherapy with vinblastine and steroid therapy, which is well tolerated in children and has an approximately 85% response rate [9].

The research in the pathogenesis of LCH has offered the opportunity of new targeted therapy. Trials in adult patients have reported high response rates to MAPK pathway‐directed targeted therapy with BRAFV600E or MEK inhibition for LCH [10]. Retrospective series report similar findings for children with LCH. However, despite high response rates, MAPK pathway inhibition does not appear to be curative. Moreover, as observed in patients with solid tumors, the BRAFV600E allele can be detected in the circulating cell-free DNA (ccf-DNA) of patients with severe BRAFV600E mutated LCH. Quantification of the plasmatic BRAFV600E load for this group of patients can precisely monitor response to therapy [9, 11].

The aim of the present study is to describe the demographic data, the clinical characteristics and the therapeutic outcome in cases of children diagnosed with Langerhans Histiocytosis with BRAFV600E mutation at a Greek pediatric hematology-oncology reference center from 2012-2024.

Methods

Patients

This is a retrospective study, which included children and adolescents with LCH diagnosed and treated in our unit between 2012-2024. We recorded demographic data and clinical information regarding the extent of disease, the BRAFV600E status, the type of treatment and the response to chemotherapy.

Based on site and extent of disease at diagnosis, patients were either treated with chemotherapy with protocol LCH II/III/IV or local therapy (biopsy, curettage, and/or intralesional steroids).

The risk categories were defined according to the LCH-IV protocol. Response to chemotherapy was evaluated at the end of 6 weeks of induction therapy with vinblastine and prednisolone (Initial course 1). Informed consent of the patients/guardians was obtained prior to enrolment of the prospective cases. The study was approved by the institutional scientific board committee (18141/2018).

BRAF Mutation Detection

Formalin-fixed-Paraffin-embedded (FFPE) blocks or fresh biopsy specimens of confirmed cases of LCH were analyzed.

BRAFV600E mutation analysis was performed using real time PCR (RT-PCR) mutation detection assay according to the manufacturer’s protocol in Formalin-fixed Paraffin-embedded blocks or fresh biopsy tissue of patients with diagnosis of LCH.

In selected patients Circulating Cell-Free (ccf) DNA BRAFV600E mutation analysis in plasma at the timepoint of first diagnosis of LCH was performed. For this purpose, blood samples were collected into EDTA-containing vacutainer tubes. Ccf-DNA was isolated using the QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions and stored at −80°C until quantification. A QX200TM Droplet Digital PCR System (Bio-Rad) was used to determine the presence and level of ccf BRAFV600E.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables and number (Percentage) and Median (IQR: 25th–75th) for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Age at diagnosis was grouped to (a) < 3 years and (b) ≥3 years. The Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare BRAFV600E status with categorical variables of subject and disease characteristics. Mann–Whitney U test was performed to test the BRAF status with continuous variables of subject and disease characteristics. Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the overall survival (OS) and event - free survival (EFS). Event for OS and EFS was (a) death and (a) relapse or (b) death or (c) second malignancy whichever occurred first, respectively. Log-rank test was performed to compare the Kaplan-Meier curves to BRAF status.

P-value < 0.05 was assigned as the threshold for statistically significant findings. All statistical analyses were conducted using the statistical software STATA version 18.0 (Stata Corp. 2023. Stata Statistical Software: Release 18. College Station, TX: Stata Corp LLC).

Results

During the specified period of 2012 to 2024, 47 subjects were diagnosed with LCH. Of them, 28 (59.6%) were tested for BRAFV600E somatic status. This latter group of patients included 17 males and 11 females, with a median age at diagnosis being 5.68 (IQR; 1.71 - 8.83) and more than one-third of the subjects being below the age of 3 years at the time of diagnosis. The majority of these subjects, 26/28 (92.86%), were diagnosed with single-system LCH, with a higher percentage 21/26 (80.77%) involving only one organ or system -bone 17/26 (65.38%), skin 6/26 (23.08%) and other 3/26 (11.54%). Follow up time for these subjects was 1.88 (IQR; 0.87 – 5.27) years. Sixteen (57.14%) subjects were positive for the BRAFV600E mutation, while twelve (42.86%) were negative. (Table 1).

|

Subjects studied |

Subjects non-studied |

Overall |

|

|

for BRAFV600E |

for BRAFV600E |

(Ν=47) |

|

|

(Ν=28) |

(Ν=19) |

||

|

Sex |

|||

|

Male |

17 (60.71%) |

10 (52.63%) |

27 (57.45%) |

|

Female |

11 (39.29%) |

9 (47.37%) |

20 (42.55%) |

|

Age at diagnosis, years [a] |

5.68 (1.71 - 8.83) |

7.34 (4.53 - 10.64) |

6.20 (2.21 - 10.42) |

|

<3 years |

10 (35.71%) |

3 (15.79%) |

13 (27.66%) |

|

≥3 years |

18 (64.29%) |

16 (84.21%) |

34 (72.34%) |

|

LCH classification |

|||

|

SS |

26 (92.86%) |

17 (89.47%) |

43 (91.49%) |

|

MS |

2 (7.14%) |

2 (10.53%) |

4 (8.51%) |

|

Organ/ system involved [b] |

|||

|

Unifocal |

21 (80.77%) |

14 (82.35%) |

35 (81.40%) |

|

Multifocal |

5 (19.23%) |

3 (17.65%) |

8 (18.60%) |

|

Site at diagnosis [b] |

|||

|

Bone |

17 (65.38%) |

15 (88.24%) |

32 (74.42%) |

|

Skin |

6 (23.08%) |

1 (5.88%) |

7 (16.28%) |

|

Lung |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Pituitary |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Lymph nodes |

0 |

1 (5.88%) |

1 (2.33%) |

|

Other |

3 (11.54%) |

0 |

3 (6.98%) |

|

Central nervous system risk [b] |

|||

|

No |

18 (69.23%) |

16 (94.12%) |

34 (79.07%) |

|

Yes |

8 (30.77%) |

1 (5.88%) |

9 (20.93%) |

|

Treatment |

|||

|

Observation |

13 (46.43%) |

6 (31.58%) |

19 (40.43%) |

|

Chemotherapy |

15 (53.57%) |

13 (68.42%) |

28 (59.57%) |

|

Follow-up time, years [a] |

1.88 (0.87 – 5.27) |

1.49 (0.78 - 5.76) |

1.78 (0.78 – 5.61) |

|

LCH= Langerhans cell histiocytosis; SS= Single system; MS= Multisystem; RO- = No risk organ involvement; RO+= Risk organ involvement. [a] Median (IQR: 25th-75th). [b] Percentages are based on subjects diagnosed with SS. |

|||

Table 1: Main characteristics of subjects.

Patients’ characteristics and disease outcomes were compared to BRAF status; There was a trend for detection of BRAFV600E mutation in patients younger than 3 years (p= 0.069) and with a positive correlation with elevated LDH levels (p=0.068). The BRAF positive status was reported in all MS cases, but no statistically significant differences were found (p= 0.492) (Table 2).

|

|

Subjects tested for BRAFV600E |

|

|

|

(Ν=28) |

|||

|

|

Positive |

Negative |

p-value |

|

(N1=16) |

(N2=12) |

||

|

Age at diagnosis in years, n (%) |

8 (50.00%) |

2 (16.67%) |

0.069* |

|

< 3 years |

8 (50.00%) |

10 (83.33%) |

|

|

≥ 3 years |

|||

|

Sex, n (%) |

7 (43.75%) |

4 (33.33%) |

0.576* |

|

Female |

9 (56.25%) |

8 (66.67%) |

|

|

Male |

|||

|

LCH classification, n (%) |

14 (87.5%) |

12 (100.0%) |

0.492** |

|

Single system |

2 (12.5%) |

0 |

|

|

Multisystem |

|||

|

Subtype n (%) |

0.837** |

||

|

MS |

2 |

||

|

SS-bone |

9 (56.25%) |

8 (66.67%) |

|

|

SS-skin |

4 (25.00%) |

2 (16.67%) |

|

|

SS-other |

1 (6.25%) |

2 (16.67%) |

|

|

Site at diagnosis, n (%) [a] |

0.634* |

||

|

Bone |

9 (64.29%) |

8 (66.67%) |

|

|

Skin |

4 (28.57%) |

2 (16.67%) |

|

|

Other |

1 (7.14%) |

2 (16.67%) |

|

|

CNS risk n (%) [a] |

|||

|

No |

10 (71.43 %) |

8 (66.67%) |

0.793* |

|

Yes |

4 (28.57 %) |

4 (33.33%) |

|

|

Chemotherapy, n (%) |

|||

|

No |

9 (56.25%) |

4 (33.33%) |

0.229* |

|

Yes |

7 (43.75%) |

8 (66.67%) |

|

|

Relapse, n (%) |

|||

|

No |

15 (93.75%) |

11 (91.67%) |

0.832* |

|

Yes |

1 (6.25%) |

1 (8.33%) |

|

|

Diabetes at diagnosis |

|||

|

No |

15 (93.75%) |

12 (100.00%) |

>0.999** |

|

Yes |

1 (6.25%) |

0 |

|

|

Hemoglobin (g/dL) at diagnosis (Median; 25th- 75th) |

12.8 (11.4-13.4) |

12.8 (12.6-13.2) |

0.969¥ |

|

WBC (/μL) at diagnosis (Median; 25th- 75th) |

11160 (7800 - 11490 |

9140 (7390- 9890) |

0.424¥ |

|

HCT (%) at diagnosis (Median; 25th- 75th) |

37.5 (35.6 - 40) |

38.5 (37.2 – 41) |

0.518¥ |

|

PLT (/μL) at diagnosis (Median; 25th- 75th) |

321000 (270000 - 552000) |

336000 (309000 – 432000) |

0.621¥ |

|

LDH (IU/ml) at diagnosis (Median; 25th- 75th) |

250 (218 - 330) |

206.5 (178 - 279) |

0.068¥ |

|

[a] Percentages are based on subjects with SS in each group * Chi-square test; ** Fisher exact test; ¥ Mann–Whitney U test |

|||

Table 2: BRAFV600E mutation and clinical risk factors.

Of the 28 subjects, 13/28 (46.43%) were treated with chemotherapy along with surgery, 13/28 (46.43%) with surgery only and 2/28 (7.14 %) with chemotherapy only. The treatment protocol was mainly the LCH IV (24/28 (85,71%) LCH III 3/28 (10.71%) and LCH II 1/28 (3.57%) (Table 1).

Of the 15 subjects who received chemotherapy, 3 of them are still under treatment. During the follow-up period, 10/12 patients (83.33%) remained in complete response, while two patients, who both had positive BRAF status, had, one each, resistant disease or disease progression. (Table 3).

|

Time of assessment Response assessment |

Subjects tested for BRAFV600E and received chemotherapy (Ν=12) |

||

|

Positive |

Negative |

Overall |

|

|

(N1=6) |

(N2=6) |

(N=12) |

|

|

1st evaluation |

|||

|

Complete Response |

4 (66.67%) |

6 (100.00%) |

10 (83.33%) |

|

Stable Active Disease |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Resistant Disease |

1 (16.67%) |

0 |

1 (8.33%) |

|

Disease Progression |

1 (16.67%) |

0 |

1 (8.33%) |

|

N= Number of subjects who received chemotherapy and there are no under treatment |

|||

Table 3: Response assessment following chemotherapy.

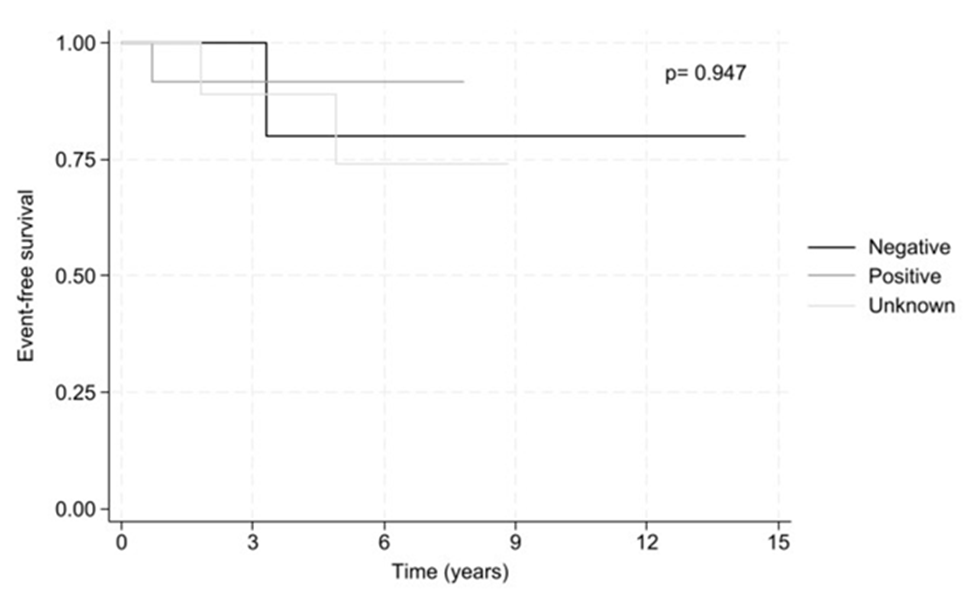

Two subjects experienced a relapse after the first evaluation at 8.6 months and 42.6 months, respectively. The 5-year overall survival was found 100%. The 5-year event-free survival was found 80.0%, 91.7% and 74.1% for negative, positive, and unknown BRAF status, respectively with no statistically significant differences (p = 0.947) (Fig. 1). More precisely, three subjects with SS (2 positive and 1 negative for BRAFV600E) relapsed during follow up.

Figure 1: 5-year event free survival by BRAF status.

ccf-DNA RESULTS

We evaluated ccf-DNA for the BRAFV600E allele in 10 patients with LCH at the timepoint of first diagnosis (8 males, mean age 8.7 years old, 5 positive for BRAF V600E at tissue biopsy).

No ccf-DNA BRAFV600E was detected in the plasma of these patients.

Discussion

In this study, in total, 47 subjects were diagnosed with LCH out of which 28 were tested for BRAF somatic status during the specified period of 2012 to 2024. We found that 57.14% of the patients tested for BRAFV600E were positive for the mutation. This frequency is similar to most of studies that demonstrate BRAFV600E mutation positivity in children with LCH at a percentage >50% [7, 12, 13].

The demographics of the patients in this report with male predominance and presentation at young ages is similar to previous studies. The median age at diagnosis in our cohort was 5.68 (IQR; 1.71 - 8.83) and more than one-third of the subjects were below the age of 3 years at the time of diagnosis, which shows small differences from other studies, where the median age at diagnosis of LCH was below 3 years old [14-16].

The majority of the subjects (92.86%) were diagnosed with single-system LCH, with a higher percentage (80.77%) involving only one organ or system-SS disease. Bone was the most frequently affected organ (65.38%), followed by skin (23.08%). These findings are in agreement with the epidemiology of LCH in pediatric patients [17-19].

The age greater than 3 years at the time of diagnosis was marginally associated with the absence of the BRAF mutation (p= 0.069). It is well defined in several studies that patients under 3 years old have more severe disease because of the presence of BRAF mutation [11]. Subjects with the BRAF mutation were marginally associated with higher LDH levels at diagnosis (p=0.068) but White blood cell counts, Platelets and Hemoglobulin were not associated with BRAF status, as it has been demonstrated in another study [11].

During the follow-up period, resistant disease and disease progression was observed only in the group of patients with positive BRAFV600E status, while all subjects with negative BRAF status reached a complete response. Two subjects (one BRAF positive and one BRAF negative) experienced relapse after having achieved remission. However, the subject with BRAF positive LCH presented two relapses, with the first one occurring in significantly shorter period than the one occurring in the subject with BRAF negative LCH. It is well established that BRAF mutation correlates with poorer prognosis and resistant or refractory disease [20, 21].

The prognosis in pediatric patients with LCH is excellent [19, 22]. At this study the overall survival was found at 100% for both BRAF positive and negative cases and the 5-year event-free survival was found 80.0%, 91.7% and 74.1% for negative, positive, and unknown BRAF status, respectively with no statistically significant differences (p = 0.947).

Although the significance of ccf DNA BRAFV600E in the plasma of patients with LCH has previously been demonstrated [11, 23], we failed to detect ccf-DNA BRAFV600E, probably due to low sensitivity threshold of the assay. The main limitations of the study are its limited size, the non-availability of samples from all the patients for evaluation of BRAFV600E and not evaluating other than the BRAF V600E somatic alterations of the MAP kinase pathway. On the other hand, this cohort of patients was treated uniformly by the same medical team and is fairly representative of the Greek population.

This is the first report on BRAF status in Greek children with LCH. Even though no statistical significance was reached, our cohort implies a correlation of BRAFV600E positivity with more aggressive disease and younger age. Further studies are required to validate these observations and to exploit the usefulness of evaluating BRAF to guide therapeutic approaches.

Funding: The study was supported by NKUA-SARG (grant 12260 and 16839).

Declaration of Competing Interest: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments: We would like to acknowledge all the patients and their families with LCH and the medical and nurse staff of the Hematology-oncology Unit.

References

- Rodriguez-Galindo C (2021) Clinical features and treatment of Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Acta Paediatr 110: 2892-2902.

- Horne A, Requena-Caballero L, Allen CE, Egeler RM, et al. (2016) Revised classification of histiocytoses and neoplasms of the macrophage-dendritic cell lineages. Blood 127: 2672-2681.

- Rodriguez-Galindo, Allen CE (2020) Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood 135: 1319-1331.

- Sconocchia T, Foßelteder J, Sconocchia G, Reinisch A (2023) Langerhans cell histiocytosis: current advances in molecular pathogenesis. Front Immunol 14: 1275085.

- Allen CE, Ladisch S, McClain KL (2015) How I treat Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood 126: 26-35.

- Emile JF, Cohen-Aubart F, Collin M, Fraitag S, Idbaih A, et al. (2021) Histiocytosis. Lancet 398: 157-170.

- Badalian-Very G, Vergilio JA, Degar BA, MacConaill LE, Brandner B, et al. (2010) Recurrent BRAF mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood 116: 1919-1923.

- Héritier S, Hélias-Rodzewicz Z, Chakraborty R, Sengal AG, Bellanné-Chantelot C, et al. (2017) New somatic BRAF splicing mutation in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Mol Cancer 16: 115.

- Héritier S, Emile JF, Hélias-Rodzewicz Z, Donadieu J (2019) Progress towards molecular-based management of childhood Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Arch Pediatr 26: 301-307.

- Gulati N, Allen CE (2021) Langerhans cell histiocytosis: Version 2021. Hematol Oncol 39: 15-23.

- Héritier S, Hélias-Rodzewicz Z, Lapillonne H, Terrones N, Garrigou S, et al. (2017) Circulating cell-free BRAF(V600E) as a biomarker in children with Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Br J Haematol 178: 457-467.

- Chakraborty R, Burke TM, Hampton OA, Zinn DJ, Har Lim KP, et al. (2016) Alternative genetic mechanisms of BRAF activation in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood 128: 2533-2537.

- Durham BH, Lopez Rodrigo E, Picarsic J, Abramson D, Rotemberg V, et al. (2019) Activating mutations in CSF1R and additional receptor tyrosine kinases in histiocytic neoplasms. Nat Med 25: 1839-1842.

- Yağci B, Varan A, Cağlar M, Söylemezoğlu F, Sungur A, et al. (2008) Langerhans cell histiocytosis: retrospective analysis of 217 cases in a single center. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 25: 399-408.

- Guyot-Goubin A, Donadieu J, Barkaoui M, Bellec S, Thomas C, et al. (2008) Descriptive epidemiology of childhood Langerhans cell histiocytosis in France, 2000-2004. Pediatr Blood Cancer 51: 71-75.

- Salotti JA, Nanduri V, Pearce MS, Parker L, Lynn R, et al. (2009) Incidence and clinical features of Langerhans cell histiocytosis in the UK and Ireland. Arch Dis Child 94: 376-380.

- İnce D, Demirağ B, Özek G, Erbay A, Ortaç R, et al. (2016) Pediatric langerhans cell histiocytosis: single center experience over a 17-year period. Turk J Pediatr 58: 349-355.

- Lee JW, Shin HY, Kang HJ, Kim H, Park JD, et al. (2014) Clinical characteristics and treatment outcome of Langerhans cell histiocytosis: 22 years' experience of 154 patients at a single center. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 31: 293-302.

- Rigaud C, Barkaoui MA, Thomas C, Bertrand Y, Lambilliotte A, et al. (2016) Langerhans cell histiocytosis: therapeutic strategy and outcome in a 30-year nationwide cohort of 1478 patients under 18 years of age. Br J Haematol 174: 887-898.

- Héritier S, Emile JF, Barkaoui MA, Thomas C, Fraitag S, et al. (2016) BRAF Mutation Correlates With High-Risk Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis and Increased Resistance to First-Line Therapy. J Clin Oncol 34: 3023-3030.

- Zeng K, Wang Z, Ohshima K, Liu Y, Zhang W, et al. (2016) BRAF V600E mutation correlates with suppressive tumor immune microenvironment and reduced disease-free survival in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Oncoimmunology 5: e1185582.

- Gadner H, Minkov M, Grois N, Pötschger U, Thiem E, et al. (2013) Therapy prolongation improves outcome in multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood 121: 5006-5014.

- Poch R, Louet SL, Hélias-Rodzewicz Z, Hachem N, Plat G, et al. (2021) A circulating subset of BRAF(V600E) -positive cells in infants with high-risk Langerhans cell histiocytosis treated with BRAF inhibitors. Br J Haematol 194: 745-749

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.