Bornman-Terblanche-Blumgart Syndrome: A Case Report

by Fournier Noémie*, Rodrigues Bruno, Gamble Lisa, Fournier Ian

Department of Internal Medecine, Hôpital de Sion (CHVR), Av. du Grand-Champsec 80, 1951 Sion, Switzerland

Department of General Surgery, Hôpital de Sion (CHVR), Av. du Grand-Champsec 80, 1951 Sion, Switzerland

*Corresponding author: Fournier Noémie, Department of Internal Medecine, Hôpital de Sion (CHVR), Av. du Grand-Champsec 80, 1951 Sion, Switzerland

Received Date: 09 January 2025

Accepted Date: 13 January 2025

Published Date: 15 January 2025

Citation: Noémie F, Bruno R, Lisa G, Ian F (2025) Bornman-Terblanche-Blumgart Syndrome: A Case Report. J Surg 10: 11229 https://doi.org/10.29011/2575-9760.011229

Abstract

Hepatic hemangioma is the most common benign liver tumour. It is generally asymptomatic but can sometimes cause abdominal symptoms and rarely Bornmann-Terblanche-Blumgart syndrome [1]. In this case report, we present a clinical example of this syndrome. A 43-year-old patient, known for a giant hepatic hemangioma, was admitted with a persistent fever of unknown origin. Infectious and autoimmune investigations proved non-contributory, and an MRCP showed signs of hemorrhagic remodeling within the known hemangioma, suggesting an inflammatory etiology for this growing lesion. She underwent a right hepatectomy and her symptoms disappeared after a few days. Bornman-Terblanche-Blumgart syndrome is an extremely rare condition, and only a handful of cases have been described. Treatment consists in surgical removal or embolization of the lesion. [2,3]

Hepatic haemangiomas are mostly asymptomatic, but in rare cases, may be associated with aesthenia and a persistent fever, as described in our patient. Given this clinical presentation, a Bornman-Terblanche-Blumgart syndrome should be included in the differential diagnosis, and, if confirmed, surgical intervention could be indicated.

Keywords: Bornman-Terblanche-Blumgart syndrome; Fever; Hepatic haemangioma; Inflammatory syndrome

Introduction

Hepatic haemangioma is often discovered incidentally and is most frequently located in the right hepatic lobe. It can sometimes cause abdominal symptoms as well as complications, such as bile duct compression, bleeding, thrombosis or rarely BornmannTerblanche-Blumgart syndrome [1]. In this article, we present a clinical case and provide an overview of hepatic haemangioma.

Clinical Case

Mrs. D is a 43-year-old Swiss patient known for a giant hepatic haemangioma, admitted due to a persistent fever over 6 months. One month after experiencing bacterial tonsillitis, treated with co-amoxicillin, the patient presented with a fever associated with aesthenia, loss of appetite, and weight loss (37 kg in 6 months). The remainder of the medical history was unremarkable. Notably, in the outpatient setting, an infectious assessment as well as a PETCT had shown no abnormalities. Upon arrival, the patient appeared ill with a decreased general condition. The cardiopulmonary, ENT, gastro-intestinal, neurological, and dermatological examinations were unremarkable, and no lymphadenopathy was found. The laboratory results showed raised inflammatory markers with a CRP of 221 mg/L and an ESR > 135 mm/h. Liver function tests were normal except for an elevated alkaline phosphatase at 272 U/L. We also noted an anemia of inflammatory origin, with a hemoglobin level of 60 g/L at its nadir and an increased fibrinogen level of 8.2 g/L without other notable hemostatic abnormalities.

A broad screening for infection was carried out (CMV, EBV, syphilis, HIV, tuberculosis, brucellosis, toxoplasmosis, Coxiella Burnetii, Bartonellosis, hepatitis B and C), all of which were negative, as were the blood cultures.

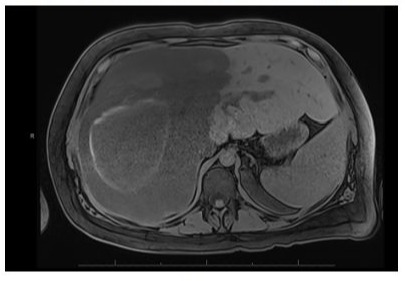

In the absence of a clear diagnosis to explain her persistent fever and inflammatory state, the etiological workup was continued looking for autoimmune diseases that can cause fever, such as lupus (ANCA, ANA, C3 and C4 complement, anti-La, anti-Ro60, anti-topoisomerase1), membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, granulomatosis with polyangitis (MPO-ANCA, PR3-ANCA), Churg-Strauss disease, scleroderma (anti-Ku, SCL70, RP11 and RP155, U3RNP, anti-NOR90, anti TH/TO, anti PMSCL 100 and anti PMSCL75), rheumatic fever (antistreptolysine O) and sarcoidosis (angioconvertase), without success. During her hospitalization, the patient complained of a new, rapidly progressing pain in the right upper quadrant, prompting an abdominal CT scan that revealed the giant hemangioma of the right liver, which had grown compared to previous imaging, without signs of rupture, active bleeding, or venous thrombosis. Given this new finding, the general surgical team was contacted. They suggested completing the radiological investigations with an MRCP, which highlighted signs of hemorrhagic remodeling within the hemangioma (Figures 1,2).

Figure 1: Giant right hepatic lobe hemangioma without signs of rupture, venous thrombosis, or active bleeding.

Figure 2: MRCP showing a giant hemangioma of the right liver with intralesional hemorrhagic changes.

Given this new finding, a Bornman-Terblanche-Blumgart syndrome was strongly suspected. The syndrome was first described in 1987 and is a combination of fever, an inflammatory syndrome, raised fibrinogen, and unremarkable hepatic parameters in a patient diagnosed with a hepatic hemangioma and abdominal pain [4]. Radiological examinations revealed a hyperintense mass with hypointense central areas indicating thrombosis on MRI (T2) or signs of hemorrhage, as was the case with our patient [4,5]. Therapeutic options included hepatic resection, enucleation, or arterial embolization, and are indicated based on the size of the lesion [2,3,6].

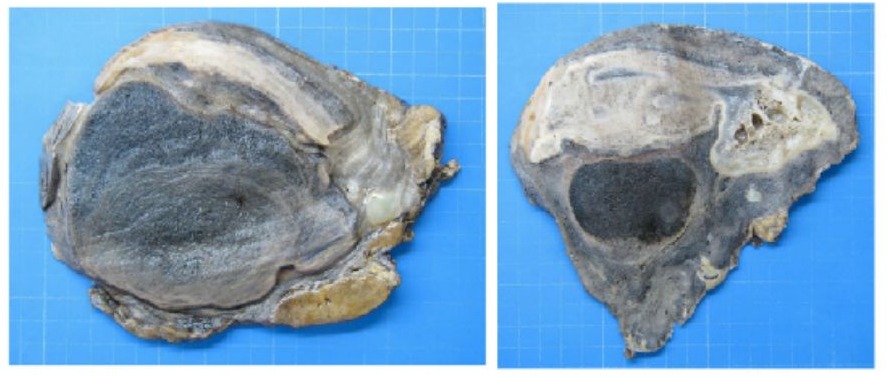

Surgical intervention was proposed in our case and accepted by the patient. A right hepatectomy was performed in July 2022, and the histopathological report revealed the presence of a large non-encapsulated mass measuring 24x18x15 cm, with a heterogeneous appearance including a more hemorrhagic central area as well as some fibrous regions. Microscopic examination showed vascular spaces lined with atypical endothelial cells, separated by fibrous trabeculae. Large areas exhibited ischemic necrosis, accompanied in some places by inflammatory and hemorrhagic infiltration. Some thrombi and foci of sclerohyaline involution were also observed .

Figure 3: Hepatectomy specimen with a heterogeneous appearance, including a central hemorrhagic area alternating with a multiloculated pseudocystic appearance and fibrous regions

Mrs. D was discharged after 15 days of hospitalization, without recurrence of her fever. The outpatient follow-up revealed a progressive normalization of her inflammatory syndrome and a significant improvement in her general condition. Given the biological assessments, histopathological analysis, and resolution of symptoms after resection of the hemangioma, the diagnosis of Bornman-Terblanche-Blumgart syndrome was confirmed.

Discussion

Hepatic hemangioma is the most common benign liver tumor, with an unclear etiology. The incidence ranges from 0.4% to 20% of the population, and women are more affected than men [1]. The classic age of presentation is between 30 and 50 years, and exposure to oestrogen may contribute to an increase in the size of the lesion [7]. Giant hemangioma is often described as being greater than 10 cm and predominantly affects the right hepatic lobe. In most cases, it is asymptomatic and discovered incidentally, but it can sometimes lead to gastro-intestinal symptoms (abdominal pain, nausea/ vomiting, early satiety). Liver function tests are almost never perturbed, except in cases of complications such as thrombosis, bleeding, or bile duct compression. The diagnostic approach relies primarily on abdominal ultrasound, which reveals a lesion < 3 cm that is homogeneous, hyperechoic, and well-defined. These criteria are applicable to a non-cirrhotic patient with no history of oncological disease. Conversely, in cases of atypical imaging on abdominal ultrasound, an abdominal MRI or CT scan should also be performed, with IV contrast in cases of cirrhosis or oncological disease with a risk of liver metastasis [8,9].

Biopsy is indicated in very rare cases due to the significant risks of bleeding but may sometimes be necessary in cases of inconclusive radiological examinations.

The differential diagnoses include hepatocellular carcinoma, especially in the presence of liver cirrhosis, and metastatic lesions in the context of active oncological disease. The main possible complications currently described in the literature are thrombosis, bleeding (0.47%), bile duct compression, and more rarely, Kasabach-Merritt syndrome. There is no relationship between the size of the hemangioma and the occurrence of complications [10] but oestrogens appear to be involved in the progression of the lesion size [11,12].

The Bornman-Terblanche-Blumgart syndrome, very rarely described, is also a possible complication of hemangioma. Affected patients present with an undetermined fever, asthenia, and involuntary weight loss. Laboratory findings reveal an inflammatory syndrome, as well as raised fibrinogen and alkaline phosphatase, without other perturbed liver function tests in most of the described cases [4]. Radiological examinations reveal a hyperintense mass with hypointense central areas indicating thrombosis on MRI (T2) or signs of hemorrhage, as with our patient [4,5] The pathophysiology is still unclear, but appears to be related to the presence of thrombosis and necrosis within the hemangioma, which are responsible for the inflammation. All described cases resolve after surgical intervention, and histopathological examination often reveals the presence of thrombi and necrosis in the hemangioma [4]. In the absence of symptoms and in the case of a hemangioma ≤ 5 cm, no follow-up is indicated. However, if the lesion is > 5 cm, an MRI with contrast injection should be performed at 6 and 12 months. Follow-up can be discontinued if the size of the lesion remains stable (≤ 3 mm/ year). Otherwise, discussion regarding further management in a multidisciplinary meeting is indicated.

In symptomatic patients, management is carried out on a case-bycase basis. The different surgical options are hepatic resection or enucleation [2]. In the case of a hemangioma > 10 cm, adjuvant arterial embolization may be performed preoperatively to reduce the size of the lesion [6]. Arterial embolization can also be performed as therapy [3]. The prognosis for patients with hepatic hemangioma is excellent, and the occurrence of symptoms or complications remains rare [13].

Conclusion

Hepatic haemangioma is asymptomatic in most cases. However, in very rare situations, it can lead to inflammatory complications, as described in the Bornman-Terblanche-Blumgart syndrome. Very few cases have been described in the literature to date, but all report patients with prolonged fever, asthenia, and involuntary weight loss. Laboratory tests reveal a chronic inflammatory syndrome, with elevated fibrinogen and alkaline phosphatase levels, as found in our patient.

References

- Leon M, Chavez L, Surani S (2020) Hepatic hemangioma: What internists need to know. WJG. 7 janv 26: 11‑20.

- Liu Y, Wei X, Wang K, Shan Q, Dai H, et al. (2016) Enucleation versus Anatomic Resection for Giant Hepatic Hemangioma: A Meta‑Analysis. Gastrointest Tumors 3: 153‑162.

- Sun JH, Nie CH, Zhang YL, Zhou GH, Ai J, et al. (2015) Transcatheter Arterial Embolization Alone for Giant Hepatic Hemangioma. Lu SN, éditeur. PLoS ONE 10: e0135158.

- Pol B, Disdier P, Treut YP, Campan P, Hardwigsen J, et al. (1998) Inflammatory process complicating giant hemangioma of the liver: Report of three cases. Liver Transpl. Mai 4: 204‑207.

- Yoshimizu C, Ariizumi S, Kogiso T, Sagawa T, Taniai M, et al. (2022) Giant Hepatic Hemangioma Causing Prolonged Fever and Indicated for Resection. Intern Med 61: 1849‑1856.

- Zhou JX, Huang JW, Wu H, Zeng Y (2013) Successful liver resection in a giant hemangioma with intestinal obstruction after embolization. WJG. 21 mai 19: 2974‑2978.

- Bajenaru N, Balaban V, Săvulescu F, Campeanu I, Patrascu T (2015) Hepatic hemangioma ‑review‑. Journal of Medicine and Life Vol 8, Special Issue 8: 4‑11.

- Leifer DM, Middleton WD, Teefey SA, Menias CO, Leahy JR (2000) Follow‑up of Patients at Low Risk for Hepatic Malignancy with a Characteristic Hemangioma at US. Radiology. janv 214: 167‑172.

- Caturelli E, Pompili M, Bartolucci F, Siena DA, Sperandeo M, et al. (2001) Hemangioma‑like Lesions in Chronic Liver Disease: Diagnostic Evaluation in Patients. Radiology. août 220: 337‑342.

- EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of benign liver tumours. Journal of Hepatology. août 65: 386‑398.

- Saegusa T, Ito K, Oba N, Matsuda M, Kojima K, et al. (1995) Enlargement of Multiple Cavernous Hemangioma of the Liver in Association with Pregnancy. Intern Med 34: 207‑211.

- Conter RL (1988) Recurrent Hepatic Hemangiomas. Ann Surg 207.

- Marrero JA, Ahn J, Reddy RK (2014) ACG Clinical Guideline: The Diagnosis and Management of Focal Liver Lesions. American Journal of Gastroenterology. Sept 109: 1328‑1347.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.