Bacterial Resistance Profiles to Antibiotics in Hospital and Community Isolates from Cytobacteriological Urine Examination, 2021-2022, Gabon

by Romeo Wenceslas Lendamba1,2*, Pierre Philippe Mbehang Nguema3, Rodrigue Mintsa Nguema3,Christophe Roland Nzinga Koumba3, Armel Mintsa Ndong4, Ghyslain Mombo-Ngoma1,5, Landry Erik Mombo6

1Centre de Recherches Médicales de Lambaréné (CERMEL), Department of Clinical Operations, PB: 242, Lambaréné, Gabon

2Ecole Doctorale Régionale (EDR) d’Afrique Centrale en Infectiologie Tropicale de Franceville, PB: 876, Franceville, Gabon

3Institut de Recherche en Écologie Tropicale, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique et Technologique (IRET/CENAREST), Microbiology Laboratory, PB : 13345, Libreville, Gabon

4Laboratoire d’Analyse médicale du Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Libreville, PB: 2228 Libreville, Gabon

5Bernard Nocht Institute of Tropical Medicine (BNITM), Bernhard-Nocht-Str. 74D-20359 Hamburg, Germany

6University of Sciences and Technology of Masuku (USTM), Faculty of Sciences, Department of Biology, PB: 976, Franceville, Gabon

*Corresponding Author: Romeo Wenceslas Lendamba, Centre de Recherches Médicales de Lambaréné (CERMEL), Department of Clinical Operations, PB: 242, Lambaréné, Gabon

Received Date: 17 November 2025

Accepted Date: 21 November 2025

Published Date: 25 November 2025

Citation: Lendamba RW, Mbehang Nguema PP, Mintsa Nguema R, Nzinga Koumba CR, Mintsa Ndong A, Mombo-Ngoma G, et al. (2025). Bacterial Resistance Profiles to Antibiotics in Hospital and Community Isolates from Cytobacteriological Urine Examination, 2021-2022, Gabon. Ann Case Report. 10: 2452. https://doi.org/10.29011/2574-7754.102452

Abstract

This study aimed to assess bacterial resistance to antibiotics in isolates obtained from cytobacteriological urine tests (ECBU) at the National Public Health Laboratory. The findings indicate that urinary tract infections are caused by Gram-negative bacilli (primarily Enterobacteriaceae) and Gram-positive cocci (mainly Staphylococcus spp., Enterococcus spp., and Group B β hemolytic Streptococcus). Among Enterobacteriaceae, Escherichia coli is the most prevalent bacterium (73, 27.8%), followed by Klebsiella pneumoniae (15, 5.7%) and Serratia odorifera (12, 4.6%). Among the Gram-positive cocci, only the genera Staphylococcus (42, 16.0%), Enterococcus (30, 11.4%) were isolated along with Streptococcus agalactiae (2, 0.7%).

Most Gram-negative bacilli exhibited primary resistance to Beta-lactams, Aminoglycosides, Quinolones/Fluoroquinolones, and Sulphonamides. Gram-positive cocci were resistant to Beta-lactams, Sulphonamides, Aminoglycosides, Rifampicin, and Glycopeptides. Certain resistance profiles observed, such as resistance to amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, ticarcillin/clavulanic acid, piperacillin/tazobactam, and cephalosporins in Gram-negative bacilli, suggest the presence of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)producing strains. In Gram-positive cocci, resistance to vancomycin and/or teicoplanin in Enterococcus spp., Staphylococcus spp., and even Streptococcus agalactiae implies the presence of van A/B phenotypes; in addition, oxacillin resistance in Staphylococcus strains suggests the presence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus (MRSA). These resistance profiles are among the most closely monitored worldwide, and their increasing emergence could result in nearly 4,750,000 deaths in Africa by 2050.

Keywords: Bacterial Resistance; Cytobacteriological Urine Examination; Gram-Negative Bacilli and Gram-Positive Cocci; Antibiotic Resistance Profile; Penicillin Reduced Susceptibility in Group B Streptococcus in Gabon.

Introduction

Nowadays, urinary tract infection (UTI) has become a common condition, ranking as the second most frequent community-acquired bacterial infection after respiratory infections [1]. It is also the primary reason for microbiological testing, with a global incidence of around 250 million cases annually [2]. Cytobacteriological urine testing (ECBU) is a key examination for diagnosing UTIs [3] and, despite its apparent simplicity, it requires a rigorous methodology whatever the circumstances. It involves cytological and bacteriological analyses that provide insight into the cells and microorganisms present in the urine, with identification through various laboratory techniques. ECBU is a direct bacteriological diagnostic method, confirming bacterial infection [4].

However, due to the increasing prevalence of acquired antibiotic resistance, an antibiogram is now routinely performed in all cases of urinary tract infections to determine the antibiotic susceptibility of the bacterial causative agent [5].

This retrospective study aimed to evaluate bacterial resistance to antibiotics in bacterial isolates identified in ECBUs from 2021 to 2022 and to examine the associated epidemiological factors.

Material and Methods Study type

This retrospective study was conducted from March to April 2023 at the National Public Health Laboratory (Libreville) as part of a final-year internship. Data from ECBUs conducted between January 2021 and September 2022 were retrieved from health records stored in the LNSP archives during an undergraduate internship.

Study population

A total of 280 urine samples were analyzed over two years. The study population included people of all ages, from both community and hospital settings, requesting ECBU at the LNSP. These data were handheld considering socio-demographic information.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This study involved all male and female patients of any age and from any background requesting ECBU at the LNSP, with complete socio-demographic information.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Directorate of the LNSP and the Directorate of the Institute for Tropical Ecology Research (IRET) at the National Centre for Scientific and Technological Research (CENAREST) during the study period.

Data collection

Data collection involved recording all patient information from the time urine samples were received until results were available. This information included patient details and urine samples delivered to the laboratory in a urine pot. Urine containers were sealed, labelled, and accompanied by a prescription specifying the time of sampling, type of transport to the laboratory, and transport temperature. Socio-demographic and clinical data for each patient were collected through a structured questionnaire, which also covered bacterial culture conditions.

Bacterial culture and identification involved aseptically inoculating 10 µL of whole urine with a sterile single-use loop in a Class 2 microbiological safety cabinet. The inoculation was performed on Cystine-Lactose-Electrolyte-Deficient (CLED, BioMérieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France), Eosin Methylene Blue (EMB, BioMérieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France), and Chapman agar (BioMérieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France) media. Urine samples were inoculated within two hours of collection to prevent false positives.

Inoculated media were systematically incubated aerobically in a bacteriological incubator at +35°C for 18 to 24 hours. Colony counts ≥ 10^5 colony-forming units (CFU) per mL of urine were considered positive according to Kass’s criteria (Hay et al., 2016). This threshold is applied regardless of the patient’s sex or isolated pathogen. Cultures with colony count below 10^5 CFU/ mL suggested potential contamination and cultures with more than two different colony types were considered contaminated.

Presumptive identification of isolates involved Gram staining, oxidase testing to differentiate fermenting from non-fermenting Gram-negative bacilli, and catalase testing to distinguish Staphylococcus from Streptococcus species. Full identification of genus, species, and subspecies was achieved using Api 10S and Api 20E galleries (bioMérieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France) for Gramnegative bacilli, Api Staph (bioMérieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France) for Staphylococcus, and Api Strep (bioMérieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France) for streptococci.

Antibiotic susceptibility testing for some isolates was conducted using the disk diffusion method (Kirby-Bauer) [6] on MuellerHinton (MH, bioMérieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France) agar following methodological recommendations and European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) guidelines in effect at the time of interpretation. Other tests were performed using ATB Staph systems. Briefly, MH agar plates were inoculated, by swabbing, with a standardised suspension (0.5 McFarland) of each isolate from 24-hour primary cultures. Antibiotic disks (Oxoid, Basingstoke Hampshire, UK) were placed on each inoculated plate, which was then incubated at +35°C for 24 hours. Inhibition zone diameters around each antibiotic disk were interpreted according to EUCAST criteria.

The following antibiotic disks were used for Gram-negative isolates: Ampicillin, Amoxicillin, Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, Cefepime, Cefalotin, Cefotaxime, Cefoxitin, Ceftazidime, Cephalexin, Ertapenem, Gentamicin, Imipenem, Nalidixic acid, Ofloxacin, Piperacillin, Tetracycline, Ticarcillin, Tobramycin, and Trimethoprim/sulfonamide.

For Gram-positive isolates, the following antibiotics were used: Penicillin G, Oxacillin, Cefoxitin, Vancomycin, Lincomycin, Erythromycin, Pristinamycin, Tetracycline, Fusidic acid, Chloramphenicol, Ofloxacin, Rifampicin, Tobramycin, Gentamicin, Clindamycin, Quinupristin-dalfopristin, Linezolid, Ciprofloxacin, Levofloxacin, and Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

Statistical analysis

Data were statistically analysed using SPSS 20 and Excel 10. Bibliographic references were introduced and formatted in the manuscript using EndNote 20.

Results

Observed bacteriological profiles

Two groups of bacteria were isolated: Gram-negative bacilli (GNB) and Gram-positive cocci. These bacteria were isolated either individually in each urine sample or in association with each other. In total, 150 Gram-negative bacilli (GNB) were isolated out of 280 bacteria, accounting for 53.6% (150/280). These Gram-negative bacilli were mainly Enterobacteriaceae, including E. coli (n=73, 26%), Citrobacter braakii (n=1, 0.4%), Citrobacter farmeri (n=2, 0.7%), Citrobacter koseri (n=2, 0.7%), Enterobacter aerogenes (n=3, 1.4%), Enterobacter amnigenus (n=1, 0.4%), Enterobacter cloacae (n=5, 1.8%), Klebsiella oxytoca (n=10, 3.6%), Klebsiella pneumoniae (n=22, 7.9%), Proteus mirabilis (n=2, 0.7%), Proteus penneri (n=1, 0.4%), Serratia liquefaciens (n=3, 1.4%), Serratia marcescens (n=10, 3.6%), Serratia odorifera (n=13, 4.6%), and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis (n=1, 0.4%). Non-Enterobacteriaceae Gram-negative bacilli were primarily represented by Acinetobacter baumannii (n=1, 0.4%).

A total of 116 Gram-positive cocci (n=41.4%) were isolated, including Staphylococcus aureus (n=44 cases, 15.7%), Staphylococcus spp. (n=30, 10.7%), Staphylococcus saprophyticus (n=12, 4.3%), the Enterococcus genus (n=30, 10.7%) and Streptococcus agalactiae (n=2, 0.7%).

Some isolates were associations between Gram-negative bacilli and Gram-positive cocci, totalling 4 cases (1.4%). These associations included Klebsiella oxytoca with Staphylococcus aureus (n=2,

0.7%), Staphylococcus aureus with Escherichia vulneris (n=1, 0.4%), and Staphylococcus saprophyticus with Serratia odorifera (n=1, 0.4%).

Among these Gram-negative bacilli and Gram-positive cocci, SKAE bacteria (S: Staphylococcus aureus, K: Klebsiella pneumoniae, A: Acinetobacter baumannii, E: Enterobacteriaceae) present the greatest clinical challenge for surveillance and management of antibiotic resistance.

Socio-clinical characteristics of the study patients

A total of 280 urine samples were collected over two years (January to December 2021; January to September 2022). The majority of samples were collected in 2022 (n=181, 64.6%). Females were predominant (n=218, 77.9%) compared to males (n=62, 22.1%), with an average patient age of 35.84 ± 19.03 years. Most patients were outpatients (n=256, 91.4%), as opposed to inpatients (n=24, 8.6%). The most common symptoms observed with the urine cultures were: micturition pain (n=32, 11.4%), infection (n=27, 9.3%), burning micturition (n=23, 8.3%), pelvic pain (n=15, 5.4%), pyuria (n=11, 3.9%) and dysuria (n=11, 3.9%). Most patients were not on treatment (n=210, 75%), compared to those who were under treatment (n=70, 25%). Patients without a history of urinary tract infections were more numerous (n=220, 78.6%) than those with a history of urinary infections (n=60, 21.4%).

Antibiotic susceptibility

Antibiotic resistance in Gram-negative bacilli

Antibiotic susceptibility testing allows bacterial strains to be classified as “Sensitive,” “Intermediate,” or “Resistant.” In this study, which aimed to assess antibiotic resistance, only resistant strains were considered.

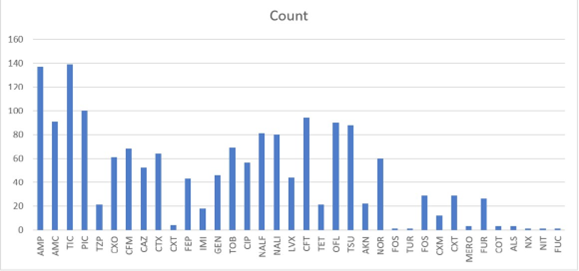

Overall resistance

The results on antibiotic resistance in Gram-negative bacilli showed variable bacterial resistance. It was highest in the four main families of antibiotics most commonly used as firstline treatments for human infections, particularly urinary tract infections. These include: Beta-lactams (particularly Penicillins such as Ampicillin, Amoxicillin+Clavulanic acid, Ticarcillin, Piperacillin), Cephalosporins (especially 1st Generation (Cefalotin), 3rd Generation (Cefixime, Cefotaxime, Cefuroxime, Ceftazidime) and 4th Generation (Cefepime)), Sulfonamides

(Trimethoprim+Sulfamethoxazole (co-trimoxazole)), Quinolones/Fluoroquinolones (especially Ofloxacin, Nalidixic acid, Ciprofloxacin, Levofloxacin, and Norfloxacin), and Aminoglycosides (Tobramycin, Gentamicin).

However, resistance to Carbapenems (Imipenem, Meropenem), which are the last-resort antibiotics for multi-resistant Gramnegative bacilli, remains very low (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Overall Antibiotic Resistance in Gram-negative Bacilli (GNB)

Global resistance phenotypes (Table 1)

When a bacterium is resistant to at least three antibiotics from two different families, it is classified as multidrug-resistant (MDR) [7]. In our study, the rate of MDR Gram-negative bacilli (GNB MDR) was 32.8% (92/280), while the rate of susceptible GNB (GNB-S) was 12.5% (35/280). The most commonly used antibiotics were from the beta-lactam family, including Ampicillin, Amoxicillin+Clavulanic acid, Cefalotin, Ceftazidime, Cefotaxime, and Cefepime. These were followed by Ofloxacin, Nalidixic acid, Quinolones/Fluoroquinolones, Gentamicin, Tobramycin, and Co-trimoxazole.

Resistance phenotypes for extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) production

All bacilli producing these enzymes showed resistance to Amoxicillin/Ampicillin, Amoxicillin+Clavulanic acid, Ticarcillin, Piperacillin, Ceftazidime, Cefotaxime, and Cefepime. In this study, 22.86% (64/280) of Gram-negative bacilli appeared to produce ESBLs (Table 1). These bacteria also demonstrated resistance to other antibiotic families, classifying them as multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (MDR-Enterobacteriaceae).

Antibiotic resistance in Gram-positive cocci

Overall resistance

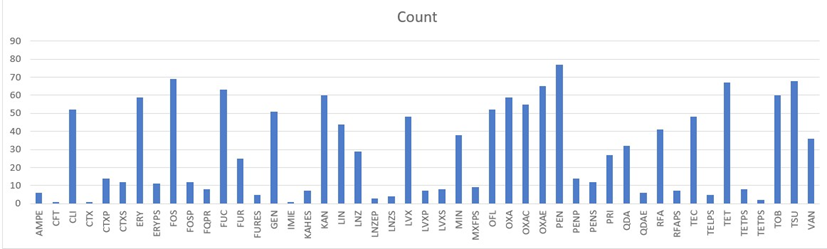

Data analysis shows that resistance is highest for penicillins and oxacillin, both from the beta-lactam family. This resistance is followed by fosfomycin, aminoglycosides (kanamycin, tobramycin), macrolides and related antibiotics (erythromycin, clindamycin, pristinamycin, and lincomycin), tetracycline, sulfonamides, and quinolones/fluoroquinolones (ofloxacin, levofloxacin) (Figure 2).

AMPE - ampicillin; CFT - cefalotin; CLI - clindamycin; CTXP - cefotaxime phosphate; CTXS - cefotaxime sulphate; ERY - erythromycin; ERYPS - erythromycin (likely referring to a specific form or preparation); FOS / FOSP - fosfomycin; FUC - fusidic acid; FUR - nitrofurantoin; GEN - gentamicin, IMIE - imipenem, KAN - kanamycin, LIN - lincomycin; LNZ - linezolid; LVX - levofloxacin; MIN - minocycline, OFL - ofloxacin; OXA-OXAE-OXAC - oxacillin; PEN-PENP-PENS- penicillin; PRI - pristinamycin; QDA – quinupristin dalfopristin; RFA - rifampicin; TEC - teicoplanin; TET-TELPS-TETPS - tetracycline; TOB - tobramycin; TSU - cotrimoxazole; VAN -vancomyci.

Figure 2: Overall Resistance in Gram-Positive Cocci

This finding mirrors that observed in Gram-negative bacteria, reinforcing that beta-lactams, aminoglycosides, sulfonamides, and quinolones/fluoroquinolones are commonly used as first-line treatments for infections in clinical practice. The high resistance to oxacillin and penicillin also suggests the likely production of methicillinase by some bacterial strains. Additionally, the resistance to vancomycin and teicoplanin indicates the possible presence of vancomycin-resistant strains.

Resistance phenotypes (Table 2)

After processing the data, taking into account all socio-demographic parameters, 41.4% (116/280) of Gram-positive cocci were observed. The presence of methicillin-resistant cocci, indicated by resistance to oxacillin (Dibah et al., 2014), was noted. Specifically, 14.3% (40/280) of Staphylococcus aureus strains were methicillinresistant. Additionally, 3.9% (11/280) of Staphylococcus aureus strains were resistant to vancomycin, 2.5% (7/280) Staphylococcus saprophyticus, and 4.6% (13/280) Staphylococcus spp. strains exhibited resistance to both vancomycin and teicoplanin, indicating a vanA phenotype. Meanwhile, 0.4% (1/280) of Staphylococcus aureus and 0.4% (1/280) of Staphylococcus spp. strains were only resistant to vancomycin, indicating a vanB phenotype. A low presence of 0.7% (2/280) of Enterococcus strains resistant to both vancomycin and teicoplanin (vanA phenotype) was also observed (Table 2).

It is also noteworthy that the data presented in Table 2 reveal that Streptococcus agalactiae strains isolated in this study, representing 0.7% (2/280), exhibit reduced susceptibility to penicillins, notably penicillin G, resistance to vancomycin (and teicoplanin), as well as to other molecules belonging to various classes of antibiotics, thus reflecting a multidrug-resistant (MDR) profile.

Resistance and socio-demographic factors

Some socio-demographic factors can influence the emergence of bacterial resistance to antibiotics, such as antibiotic consumption during hospitalisation or otherwise, and the use of antibiotics during treatment. However, the results of this study show that the difference in the averages between the multi-drug resistant (MDR) bacteria isolated during urine culture (ECBU) does not vary before or after antibiotic consumption during hospitalisation or in community settings (p-value: 0.9493541421483).

Discussion

This retrospective study aimed to evaluate bacterial resistance to antibiotics in bacterial isolates identified in ECBUs from 2021 to 2022 and to examine epidemiological factors associated with this antibiotic resistance.

Gram-negative bacilli bearing antibiotic resistance

This retrospective study showed that Gram-negative bacilli and Gram-positive cocci were the most commonly isolated during cytobacterial urine exams. Among the Gram-negative bacilli, Enterobacteriaceae such as Escherichia coli (E. coli), Klebsiella, Proteus, Serratia, Enterobacter, and Citrobacter were isolated, with E. coli showing the highest prevalence. Among the nonenterobacteria, Acinetobacter baumannii was identified. Several studies have reported similar findings [8,9]. These results confirm that Enterobacteriaceae are the most common pathogens in urinary tract infections [8, 9, 10].

Our results showed that bacterial resistance to antibiotics was more significant for antibiotics belonging to the β-lactam family, aminoglycosides, quinolones/fluoroquinolones, and sulfonamides, which are first-line antibiotics used to treat urinary tract infections in humans [11]. However, among the Gram-negative bacilli, some resistance phenotypes to β-lactams (AMC, C1G, C2G, C3G, and C4G) observed in this study suggest the production of β-lactamases (penicillinase, cephalosporinase, or extendedspectrum β-lactamases) [12,13,14]

β-lactams and quinolones are among the most commonly prescribed antibiotics in hospitals, and their resistance has been increasing alarmingly in recent years [15].

These bacteria also exhibit resistance to at least three different antibiotic families, making them multi-drug resistant (MDR). MDR bacteria continue to emerge globally, particularly in African countries [16].

Gram-positive cocci with antibiotic resistance

Among Gram-positive cocci, Staphylococcus and Streptococcus were identified, with Staphylococcus aureus being the most common. Theses bacteria were also identified in a recent study conducted in Franceville, Gabon [17]. These bacteria are the most frequent causes of urinary tract infections [9,18]. Among the Staphylococci, S. aureus and S. saprophyticus are most commonly cited as the causes of urinary tract infections [19, 20]. However, these Staphylococci may be resistant to methicillin or vancomycin, highlighting that methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (VRSA) can cause urinary tract infections [21], as shown in our study.

The findings of this study regarding Group B Streptococcus (GBS) isolates highlight several clinically and epidemiologically concerning aspects:

- The relatively low prevalence (0.7%, i.e., 2 strains out of 280) of Streptococcus agalactiae aligns with the observations of Collin et al., (2019) who reported it to be the primary Streptococcus species implicated in community-acquired urinary tract infections globally, with a prevalence of approximately 2 to 3%. The identification of Streptococcus agalactiae strains exhibiting reduced susceptibility to penicillin, particularly penicillin G, is alarming, given that penicillin G has historically been the first-line antibiotic for the treatment of streptococcal infections, including those caused by Streptococcus agalactiae [22]. This observation is also consistent with findings from studies on invasive adult isolates in the United States [23]. The isolation of such strains could be attributed either to the emergence of penicillin tolerance mechanisms or to the potential acquisition of modifications in penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs), though these mechanisms are more typically observed in Streptococcus pneumoniae [23,24].

- Although vancomycin and teicoplanin resistance among GBS isolates is not common, our findings are in line with [25] who reported resistance to those two glycopeptides will be an emerging clinical concern. Moreover, our results correlate with those of [26] who confirmed the first two cases of vancomycin-resistant GBS in adults. This is particularly concerning as vancomycin is routinely employed in the empirical or targeted treatment of severe infections caused by Gram-positive bacteria, especially in patients with β-lactam allergies [27]. The emergence of such resistance could suggest the acquisition of resistance genes such as vanA or vanB through an enterococci plasmid able to self-transfer itself to other bacteria genus including streptococci species [28], despite these being more commonly observed in enterococci [29]. An alteration of the bacterial cell wall, reducing vancomycin’s affinity for its target, could also account for this phenomenon [30]

- Finally, the multidrug-resistant profile observed in the Streptococcus agalactiae isolates raises concerns regarding the potential limitation of therapeutic options, particularly in the context of invasive or nosocomial infections. This profile may reflect selective pressure potentially associated with the excessive or inappropriate use of antibiotics [31].

Our results also showed that certain socio-demographic factors, such as hospitalization or antibiotic therapy before the ECBU, could influence resistance profiles [3]. However, the difference between the averages of MDR isolates obtained during the ECBU before and after hospitalization or treatment was not statistically significant (p-value = 0.95). In hospitals, antibiotic consumption occurs continuously throughout the hospitalization period [32], creating and maintaining selection pressure capable of generating and maintaining antibiotic resistance [33]. Although at the beginning of hospitalization, the antibiotic treatment is not specific to the bacteria causing the infection, selection pressure for antibiotics will be created and maintained throughout subsequent, more targeted treatments [33]. This will favor the emergence of MDR bacteria. These arguments support the hypothesis that “antibiotic consumption leads to the emergence of antibiotic resistance” [34]. However, antibiotic consumption in hospital settings is not the only cause of antibiotic resistance [35]. Indeed, antibiotic use in community or veterinary settings can also contribute to the emergence of multi-resistant strains [36]; consumption of contaminated water may also be a source of the emergence of multi-resistance in community patients [37,38], explaining the significant prevalence of MDR in non-hospitalized individuals undergoing treatment.

Study limitations: In this context, further molecular investigations are warranted to characterize the resistance determinants harbored by these isolates. This would involve genetic amplification techniques, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), followed by sequencing to identify the specific resistance genes involved [39-41].

Conclusion

The cytobacteriological examination of urine (ECBU) remains the primary diagnostic tool for identifying urinary tract infections (UTIs), involving macroscopic and microscopic analyses of urine characteristics and components.

In this study, pathogenic isolates predominantly belonged to Enterobacteriaceae, Staphylococcaceae, and Streptococcaceae, exhibiting multidrug resistance (MDR). Escherichia coli was the most common Enterobacteriaceae, while Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus agalactiae represented Staphylococcaceae and Streptococcaceae, respectively. Resistance was mainly observed against first-line antibiotics, including β-lactams, quinolones/fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, and sulfonamides. Hospital selective pressure and community factors such as selfmedication and veterinary antibiotic use were identified as key drivers of antimicrobial resistance (AMR). The presence of extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs), methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), and vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) was suspected.

This rising MDR trend, including the reduced susceptibility of Group B Streptococcus to penicillin, necessitates urgent alerts to national health authorities and calls for the dissemination of findings in high-impact scientific journals.

Acknowledgement: Our deepest thanks go to the colleagues of the Laboratoire National de Santé Publique (LNSP) of Gabon who used their professionalism to help collecting these data and perform the bench work.

Conflict of interest:The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sharma AR. (2012). Antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of Escherichia coli isolated from urinary tract infected patients attending Bir Hospital. Department of Microbiology. 0: 0-0.

- Ghanbari F, Khademi F, Saberianpour S, Shahin M, Ghanbari N, et al. (2017). An epidemiological study on the prevalence and antibiotic resistance patterns of bacteria isolated from urinary tract infections in central Iran. Avicenna Journal of Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 4: 0-0.

- Chama Z, Benabbou A, Derras H, Benchiha NN, Hasnia D, et al. (2021). Bacteriological profile of urinary tract infections and antibiotic resistance profile in the Telagh region (West Algeria). Egyptian Academic Journal of Biological Sciences. C, Physiology and Molecular Biology. 13: 275-296.

- Ba R, Manga Atangana B, Hounwanou A, Loko F, Bankole H, Dossevi L (2008). Bactéries isolées des ECBU au laboratoire Central du Bénin au cours des trois dernières années chez les femmes. EPAC/UAC. 0: 0-0.

- Amira A (2020). Contribution à l’étude des examens cytobactériologiques des urines (ECBU, à Guelma). 0. 0: 0-0.

- Bauer A, Kirby W, Sherris JC, Turck M (1966). Antibiotic susceptibility testing by a standardized single disk method. American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 45: 493-0.

- Maloo A, Borade S, Dhawde R, Gajbhiye S, Dastager SG (2014). Occurrence and distribution of multiple antibiotic-resistant bacteria of Enterobacteriaceae family in waters of Veraval coast, India. Environmental and Experimental Biology. 12: 43-50.

- Badi H, Marih L, Sodqi M, Lahsen AO, Bensghir R, et al. (2018). Profil de résistance des bacilles gram négatif uropathogènes au service des maladies infectieuses. Médecine et Maladies Infectieuses. 48: S102-S102.

- Savadogo H, Dao L, Tondé I, Tamini L, Ouédraogo AI, et al. (2021). Infections du tractus urinaire en milieu pédiatrique: écologie bactérienne et sensibilité aux antibiotiques au Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Pédiatrique Charles-de-Gaulle de Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso). Néphrologie & Thérapeutique. 17: 532-537.

- Bitsori M, Galanakis E (2019). Treatment of urinary tract infections caused by ESBL-producing Escherichia coli or Klebsiella pneumoniae. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 38: e332-e335.

- Alghoribi MF (2015). Molecular epidemiology, virulence potential and antibiotic susceptibility of the major lineages of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. University of Manchester. 0: 0-0.

- Philippone A, Arlet G (2012). Entérobactéries et bêta-lactamines: phénotypes de résistance naturelle. Pathologie Biologie. 60: 112-126.

- Philippone A, Labia R, Jacoby G (1989). Extended-spectrum betalactamases. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 33: 1131-1131.

- Touati A, Benallaoua S, Kecha M, Idres N (2003). Etude des phénotypes de résistance aux β-lactamines des souches d’enterobacteries isolées en milieu hospitalier: cas de l’hôpital d’Amizour (W. Bejaia). Sciences & Technologie. A, Sciences Exactes. 0: 92-97.

- Galaon T, Banciu A, Chiriac FL, Nita-Lazar M (2019). Biodegradation of antibiotics: the balance between good and bad. 0. 0: 0-0.

- Seydou S (2021). Profil épidémiologique et bactériologique des infections urinaires à entérobactéries productrices de bêtalactamases à spectre élargi (E-BLSE) dans le service de néphrologie du CHU du Point G, Bamako, Mali. Revue Africaine et Malgache de Recherche Scientifique/Sciences de la Santé. 2: 0-0.

- Mouanga-Ndzime Y, Onanga R, Longo-Pendy NM, Bignoumba M, Bisseye C (2023). Epidemiology of community origin of major multidrug-resistant ESKAPE uropathogens in a paediatric population in South-East Gabon. Antimicrobial Resistance & Infection Control. 12: 47-47.

- Loumingou R, Sinomono DE, Koumou GG, Mobengo J (2020). Les infections urinaires de l’adulte dans le service de néphrologie du CHU de Brazzaville: aspects cliniques et évolutifs. Proteus. 2: 2-10.

- Sbiti M, Lahmadi K, Louzi L (2017). Epidemiological profile of uropathogenic enterobacteria producing extended spectrum betalactamases. The Pan African Medical Journal. 28: 29-29.

- Chiu KH, Lam RP, Chan E, Lau SK, Woo PC (2020). Emergence of Staphylococcus lugdunensis as a cause of urinary tract infection: results of the routine use of MALDI-TOF MS. Microorganisms. 8: 381381.

- Selim S, Faried OA, Almuhayawi MS, Saleh FM, Sharaf M, et al. (2022). Incidence of vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains among patients with urinary tract infections. Antibiotics. 11: 408.

- Mcguire E, Ready D, Ellaby N, Potterill I, Pike R, et al. (2025). A case of penicillin-resistant group B Streptococcus isolated from a patient in the UK. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 80: 399-404.

- Metcalf BJ, Chochua S, Gertz RE, Hawkins PA, Ricaldi J, et al. (2017). Reduced penicillin susceptibility in Streptococcus agalactiae causing invasive disease in adults, United States, 2013–2014. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 65: 1900-1907.

- Kimura K, Suzuki S, Wachino J, Kurokawa H, Yamane K, et al. (2008). First molecular characterization of group B streptococci with reduced penicillin susceptibility. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 52: 2890-2897.

- Johnson AP, Uttley AH, Woodfort N, George RC. (1990). Resistance to vancomycin and teicoplanin: an emerging clinical problem. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 3: 280-291.

- Park C, Nichols M, Schrag SJ. (2014). Two cases of invasive vancomycin-resistant group B streptococcus infection. New England Journal of Medicine. 370: 885-886.

- Sanchez-Borges M, Thong B, Blanca M, Ensina LF, GonzalezDiaz S, et al. (2013). Hypersensitivity reactions to non beta-lactam antimicrobial agents, a statement of the WAO special committee on drug allergy. World Allergy Organization Journal. 6: 18.

- Campoli-Richards DM, Brogden RN, Faulds D. (1990). Teicoplanin. Drugs. 40: 449-486.

- Zakaria ND, Hamzah HH, Salil IL, Balakrishnan V, Razak KA. (2023). A review of detection methods for vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) genes: from conventional approaches to potentially electrochemical DNA biosensors. Biosensors. 13: 294.

- Arias CA, Murray BE. (2012). The rise of the Enterococcus: beyond vancomycin resistance. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 10: 266-278.

- Berbel D, Gonzalez-Diaz A, Camara J, Ardany C. (2022). An overview of macrolide resistance in streptococci: prevalence, mobile elements and dynamics. Microorganisms. 10: 2316.

- Fridkin SM, Baggs J, Md SM, Md PM, Rubin PMA, Md MHS, et al. (2014). Vital signs: improving antibiotic use among hospitalized patients. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 69: 194-200.

- Andersson DI, Balaban NQ, Baquero F, Courvalin P, Glaser P, et al. (2020). Antibiotic resistance: turning evolutionary principles into clinical reality. FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 44: 171-188.

- Bell BG, Schellevis F, Stobberingh E, Goossens H, Pringle M. (2014). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of antibiotic consumption on antibiotic resistance. BMC Infectious Diseases. 14: 1-25.

- Mbehang Nguema PP, Onanga R, Ndong Atome GR, Obague Mbeang JC, Mabika Mabika A, et al. (2020). Characterization of ESBLproducing enterobacteria from fruit bats in an unprotected area of Makokou, Gabon. Microorganisms. 8: 138.

- Urban-Chmiel R, Marek A, Stępień-Pyśniak D, Wieczorek K, Dec M, et al. (2022). Antibiotic resistance in bacteria—A review. Antibiotics. 11: 1079.

- Chandja WBE, Onanga R, Nguema PPM, Lendamba RW, Mouanga-Ndzime Y, et al. (2024). Emergence of antibiotic residues and antibioticresistant bacteria in hospital wastewater: a potential dissemination pathway into the environment: a review. [Journal Name Missing].

- Nguema PPM, Pambou Y-B, Legnouo EAA, Lendamba RW, Dikoumba AC, et al. (2023). Resistance of Enterobacteriaceae to antibiotics in wastewaters from the Mindoube municipal landfill (Libreville, Gabon).

- Collin SM, Shetty N, Guy R, Nyaga VN, Bull A, et al. (2019). Group B Streptococcus in surgical site and non-invasive bacterial infections worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 83: 116-129.

- Dibah S, Arzanlou M, Jannati E, Shapouri R. (2014). Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance pattern of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strains isolated from clinical specimens in Ardabil, Iran. Iranian Journal of Microbiology. 6: 163.

- Hay AD, Birnie K, Busby J, Delaney B, Downing H, et al. (2016). The diagnosis of urinary tract infection in young children (DUTY): a diagnostic prospective observational study to derive and validate a clinical algorithm for the diagnosis of urinary tract infection in children presenting to primary care with an acute illness. Health Technology Assessment. 20.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.