Avicenna’s Canon of Medicine: Foundations of Plastic and Reconstructive Techniques

by Daniyal Elahi*

Research Student, Toronto Institute of Plastic Surgery, Toronto, Canada

*Corresponding author: Daniyal Elahi, Research Student, Toronto Institute of Plastic Surgery, Toronto, Canada

Received Date: 21 October 2025

Accepted Date: 27 October 2025

Published Date: 29 October 2025

Citation: Elahi D (2025) Avicenna’s Canon of Medicine: Foundations of Plastic and Reconstructive Techniques. J Surg 10: 11475 https://doi.org/10.29011/2575-9760.011475

Abstract

Avicenna (Ibn Sina, 980–1037 CE) is remembered as one of the greatest minds in medical history. His massive text, The Canon of Medicine (Al-Qanun fil-Tibb), guided physicians for centuries and continues to inspire physicians and surgeons today. While most people know him for his philosophical and scientific insights, Avicenna also described surgical ideas that connect closely with modern plastic and reconstructive surgery. In his writings, he outlined methods of eyelid surgery, carpal tunnel release, tracheostomy, nerve repair, cleft surgery, fracture treatment, and wound care. He also detailed salient points about anesthesia, sterilization, and organized surgical wards-concepts far ahead of his time. This paper looks at how Avicenna’s ideas shaped the development of modern plastic and reconstructive surgery and how his clinical observations still relate to contemporary practice. His seminal work shows that curiosity, compassion, and the attention to detail were forming the developing field of surgery over a thousand years ago.

Keywords: Avicenna; Blepharoplasty; Canon of Medicine; History of Surgery; Ibn Sina; Nerve Repair; Plastic Surgery

Introduction

It is often said that every modern discipline has roots that stretch deep into history. Contemporary plastic surgery, although known today for advanced techniques and innovative technology, is nevertheless built upon centuries of gradual discovery. When Europe entered the Dark Ages, much of classical medical knowledge was lost or ignored. In contrast, the Islamic Golden Age became a period of creativity and preservation, where scholars translated Greek and Roman texts and added discoveries of their own. Among these pioneers stood Avicenna, or Ibn Sina, whose brilliant compilation of medical knowledge changed the direction of the discipline of medicine.

Figure 1: A portrait of Al Hussain Ibn Abdullah Ibn Sina (Avicenna). CC BY-SA 4.0.

Born in 980 CE near Bukhara in what is now Uzbekistan, Avicenna showed remarkable intelligence even from a young age. He memorized the Qur’an by age ten and was honoured with the title Hafiz. Avicenna mastered logic, mathematics, and philosophy, and began studying medicine as a teenager. By the age of sixteen, he was already treating patients, and before turning twenty-one, he wrote his most famous medical treatise, The Canon of Medicine [1]. This monumental one million word, five-volume encyclopedia collected and expanded all medical knowledge available at the time. For more than six hundred years, the Canon was used as a main textbook in European and Middle Eastern universities [2,3]. Even today, Avicenna’s approach feels modern. He believed that medicine and surgery were not separate arts but two parts of one science devoted to healing. His reputation grew so widely that Sir William Osler later called him “the author of the most famous medical textbook ever written [4].”

Avicenna and The Canon of Medicine

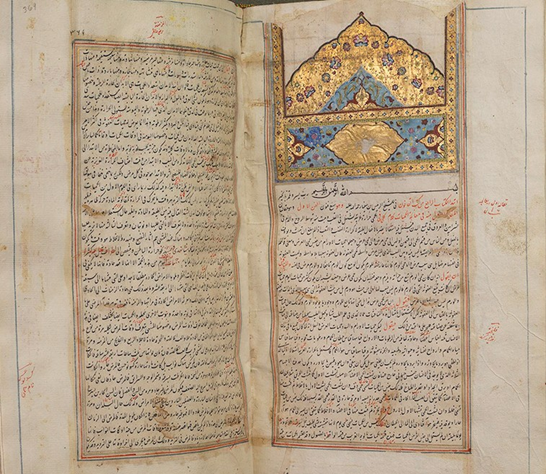

Avicenna’s Canon covers anatomy, physiology, diseases, drugs, and surgery across five distinct volumes. The five books move from theory, anatomy, diagnosis and treatment. The first volume describes medical principles while the second represents a pharmacopoeia including the listing of over 700 medicinal substances including plants, minerals and animal products. The third volume discusses diseases of individual organs while the fourth covers conditions affecting several systems including surgery. The fifth and final volume focuses on how to prepare compound remedies [5]. The fourth book is especially relevant to plastic and reconstructive surgery. This particular volume elucidates the subtleties of fractures, dislocations, wound management, cauterization, nerve and tendon repair, tracheostomy and early plastic and reconstructive principles. Avicenna offered step-by-step approach on various operations and described in great detail specialized instruments, the use of clean surgical wards, and attention to both physical and mental wellbeing of patients [6,7]. He was a firm proponent that surgeons should be students of anatomy in order to understand structures before attempting any procedure. This scientific attitude separated him from many of his physician predecessors who relied purely on tradition.

Figure 2: Opening of the fourth book of the Canon (probably early 15th century, Iran). Courtesy of the U.S. National Library of Medicine.

Principles of Surgery and Anesthesia

Avicenna treated surgery as a serious discipline requiring precision, knowledge and compassion. He explained how surgeons should prepare patients, perform operations, and prevent infection. One revolutionary idea was his advice that incisions should follow natural folds in the skin to reduce visible scarring [8]-essentially following the principle that modern plastic surgeons call relaxed skin tension lines. He recommended washing wounds with wine or rosewater for their cleansing effect [9]. Although he did not know about bacteria, his observations anticipated antisepsis. He also stressed the importance of using clean clothing and instruments, and even suggested that surgeons wear green garments to create a calm environment. Pain control fascinated Avicenna. In his book, he listed herbal mixtures such as opium, mandrake, and henbane that could induce sleep or dull pain [10,11]. He described how these agents could be combined into drinks or inhaled vaporsessentially an early form of anesthesia. He even wrote a chapter called Pain and Analgesia, classifying different types of pain in a way that resembles how modern medicine describes sensory and emotional components of pain [12]. Avicenna was a proponent of leech therapy in certain instances which he refers to as “alaq”. His application of this therapy mirrors contemporary medical management in that he advocated for their use as a controlled medical procedure. The stated purpose of their use was to remove stagnant blood, reduce inflammation and restore humoral balance, principles that reverberate even today.

Head and Neck Surgery

Avicenna’s surgical creativity extended to the head and neck region. He described operations for tonsils, tongue-tie, and nasal polyps. Most remarkably, he explained how to open the trachea to relieve airway obstruction. In his detailed instructions, he wrote that the surgeon should extend the patient’s neck, make an incision between the tracheal rings, and insert a hollow metal tube so the patient could breathe [13]. This is considered the first recorded tracheostomy in history. He even recommended using gold or silver for the tube because those metals caused less irritation and decrease infection. The same principle-maintaining an airway with a tube-remains fundamental in modern anesthetic and reconstructive surgery [14].

Ophthalmology and Blepharoplasty

Eye surgery was another area where Avicenna showed deep understanding. He discussed cataract removal and described probing the tear ducts for obstruction. Perhaps most surprising is his reference to blepharoplasty, or eyelid reconstruction, performed to improve vision and appearance [15]. He wrote about removing excess folds of skin that weighed down the eyelid, a condition that plastic surgeons treat quite commonly today. Avicenna also mentioned the use of cautery to refine eyelid contours, linking function with aesthetics-an idea that is central to the core competency of plastic and reconstructive surgery.

Orthopedics, Nerves, and Tendons

Avicenna devoted a significant portion of his book to bones, joints, tendons, and nerves. He was one of the first to clearly distinguish between these tissues [16]. He explained that movement originated in the brain and was transmitted through nerves, while tendons connected muscles to bones and ligaments held bones together. In cases of nerve injury, he advised suturing the two ends together to restore function [17]. This makes him one of the earliest advocates for surgical nerve repair. His writings also describe treatment for broken bones and dislocations, emphasizing alignment and gentle immobilization. He warned against tight bandages that could stop circulation-a description that perfectly matches compartment syndrome, identified formally only in the 19th century [18]. He even recommended delaying splinting for a few days to allow swelling to subside [19], a principle surgeons still use today.

Soft-Tissue Reconstruction and Wound Care

Avicenna recognized that successful surgery depended on healthy tissue healing. He described cleaning wounds, removing dead tissue, and applying astringent or drying agents to control infection [20]. To stop bleeding, he used pressure, ligatures, or cautery with heated metal. He also experimented with chemical cauterization using plant extracts and minerals [21]. These techniques aimed to destroy infected tissue while encouraging new growth-much like modern debridement and coagulation methods. For healing, he recommended natural substances such as Dragon’s Blood (Calamus draco), a red resin known for its soothing and antiseptic properties [22]. Modern studies confirm that this resin can stimulate tissue repair and reduce infection [23]. Avicenna’s intuitive use of botanical compounds shows how closely observation and nature were tied in early medical practice.

Aesthetic and Reconstructive Principles

Throughout his writings, Avicenna emphasized restoring both form and function. He advised making incisions that followed the relaxed skin tension lines of the body, avoiding damage to nerves and vessels, and ensuring that scars healed smoothly by avoiding areas that could potentially contract [24]. These ideas form the backbone of plastic surgery today. Some texts attribute to him procedures for male breast reduction (gynecomastia), though evidence suggests those descriptions more likely came from the earlier Persian physician Rhazes (al-Razi) [25]. Regardless, Avicenna’s understanding of proportional anatomy and cosmetic balance reflects an early appreciation of reconstructive aesthetics.

Experimental and Evidence-Based Thinking

What separates Avicenna from most physicians of his time is the insistence on testing ideas. In the Canon, he proposed seven rules for evaluating new drugs-essentially the first description of a controlled medical trial [26]. He also encouraged experiments on animals to study anatomy and pharmacology [27]. This commitment to verification mirrors what we now call evidencebased medicine. Avicenna wanted medicine to move beyond tradition and rely on proof. That mindset-questioning, testing, and documenting-remains at the heart of scientific research today.

Dermatology and Skin Surgery

Avicenna’s work in dermatology was extensive. He catalogued conditions such as psoriasis, vitiligo, leprosy, and scabies, and described how hygiene and environment influenced skin health [28]. His advice on treating wounds, ulcers, and burns emphasized cleanliness and mild natural remedies rather than harsh chemicals. He even noted how skin tension affected healing, suggesting that cuts made along certain directions would scar less-a remarkable insight for his time. His ideas link directly to the reconstructive principle of minimizing tension across wound closures.

Discussion

Reading Avicenna’s writings from a modern perspective is inspiring. Many of his principles mirror the foundations of contemporary surgery: clean technique, careful planning, and respect for anatomy. His recognition that function and appearance are connected shows a remarkably modern understanding of the human body and mind. In some ways, Avicenna foreshadowed practices developed hundreds of years later. His use of wine as an antiseptic preceded Lister’s antiseptic methods by eight centuries. His herbal anesthesia anticipated the search for surgical pain control long before ether. His suggestion to reconnect nerves anticipated 19th-century neuro-surgery. Avicenna also humanized surgery. He cared about the patient’s experience-reducing pain, avoiding disfigurement, and encouraging recovery. This balance between science and empathy still defines the best surgical care today. For young students and physicians, his story is a reminder that curiosity and dedication can overcome the limits of one’s era. Working with limited tools, Avicenna combined knowledge from Greece, Persia, and South Asia, and his own observation to create something entirely new. The Canon of Medicine bridged ancient learning with modern scientific thought, ensuring that medical knowledge did not fade but evolved.

Conclusion

Avicenna’s Canon of Medicine is not just a book of ancient theory-it is a map of how knowledge grows. His attention to anatomy, cleanliness, and patient safety built the foundation for reconstructive surgery long before the word “plastic” was used in a medical sense. From tracheostomy and eyelid repair to wound care and anesthesia, Avicenna’s insights demonstrate how far curiosity and logic can reach, even without modern technology. His approach-observing carefully, testing ideas, and caring for the whole patient-remains a model for today’s surgeons. As modern medicine continues to advance, remembering pioneers like Avicenna helps us appreciate that the roots of discovery stretch back a thousand years, to a physician who believed that healing was both a science and an art.

References

- Avicenna AS (1956) His Life and Work. Pembroke College.

- Forrester R (2016) The History of Medicine. Best Publications.

- Nasser M, Tibi A, Savage-Smith E (2009) Ibn Sina’s Canon of Medicine: 11th-century rules for assessing drugs. J R Soc Med 102: 78-80.

- Osler W (2004) The Evolution of Modern Medicine. Kessinger Publishing.

- Pakdman A, Ghaffari M (1984) The influence of Avicenna’s school of medicine on Western medicine. Acta Med Iran 26: 1-3.

- Shoja MM, Tubbs RS (2007) The history of anatomy in Persia. J Anat 210: 359-378.

- Dalfardi B, Nezhad GS (2014) Insights into Avicenna’s contributions to the science of surgery. World J Surg 38: 2175-2179.

- Beg H (2015) Surgical principles of Ibn Sina (Avicenna). Bangladesh J Med Sci 14: 217-220.

- Sandler M, Pinder R (2003) Wine: A Scientific Exploration. Taylor & Francis 2003: 35-36.

- Aziz E, Nathan B, McKeever J (2000) Anesthetic and analgesic practices in Avicenna’s Canon of Medicine. Am J Chin Med 28: 147151.

- Salehi A, Alembizar F, Hosseinkhani A (2016) Anesthesia and pain management in traditional Iranian medicine. Acta Med Hist Adriat 14.

- Tashani OA, Johnson MI (2010) Avicenna’s concept of pain. Libyan J Med 5: 5253.

- Golzari SE, Khan ZH, Ghabili K (2013) Contributions of medieval Islamic physicians to the history of tracheostomy. Anesth Analg 116: 1123-1132.

- Azizi MH (2007) The otorhinolaryngologic concepts as viewed by Rhazes and Avicenna. Arch Iran Med 10: 552-555.

- Stephenson KL (1977) The history of blepharoplasty to correct blepharochalasis. In: Gonzalez-Ulloa M, ed. Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. Springer.

- Ghannaee Arani M, Fakharian E, Ardjmand A, Mohammadian H, Mohammadzadeh M, et al. (2012) Ibn Sina’s contributions in the treatment of traumatic injuries. Trauma Mon 17: 301-304.

- Qayumi K (2012) Surgical techniques: past, present, and future. Surg Tech Dev 2: e9.

- Dabbagh A, Rajaei S, Golzari SEJ (2014) History of anesthesia and pain in old Iranian texts. Anesthesiol Pain Med 4: e15363.

- Kaadan AN (2014) Bone fractures in Ibn Sina’s medicine. World J Orthop 5: 67-68.

- Davis JH (1976) Our heritage: 1975 AAST presidential address. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 16: 425-436.

- Chauliac G (1997) Inventarium Sive Chirurgia Magna. Brill.

- Pieters L, De Bruyne T, Van Poel B (1995) In vivo wound healing activity of Dragon’s Blood (Croton spp.), a traditional South American drug, and its constituentsPhytomedicine 2: 17-22.

- Bakhtiar L (1999) The Canon of Medicine. Kazi Publications.

- Wu T (2006) Plastic surgery made easy: simple techniques for closing skin defects. Aust Fam Physician 35: 492.

- Azizi MH (2008) ed. History of Persian Medicine. Tehran Univ Press.

- Sajadi MM, Mansouri D, Sajadi MM (2009) Ibn Sina and the clinical trial. Ann Intern Med 150: 640-643.

- Aburawi EH (2007) The great professor Ibn Sina (Avicenna). Libyan J Med 2: 116-117.

- Atarzadeh F, Heydari M, Sanaye MR, Amin G (2016) Avicenna-a pioneer in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol 152: 1257.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.