Association Between the Number of Induction Cycles and Delivery Outcomes: A Retrospective Cohort Analysis

by Maryam Alsalem*, Hosni Malas, Aysha Shujaie, Reem Albinzayed, Gulmeen Raza, Rehab Ismael, Wasan Alani, Nusiba Elhassan, Shaikha Alhajri, Salma Elsheikh, Minnatullah Hamad

King Hamad University Hospital (KHUH) and the Bahrain Oncology Center, Building 2435, Road 2835, Block 228, P.O Box 24343, Busaiteen, Kingdom of Bahrain.

*Corresponding author: Maryam Alsalem, King Hamad University Hospital (KHUH) and the Bahrain Oncology Center, Building 2435, Road 2835, Block 228, P.O Box 24343, Busaiteen, Kingdom of Bahrain

Received Date: 15 January 2026

Accepted Date: 26 January 2026

Published Date: 28 January 2026

Citation: Alsalem M, Malas H, Shujaie A, Albinzayed R, Raza G, et al. (2026) Association Between the Number of Induction Cycles and Delivery Outcomes: A Retrospective Cohort Analysis. Gynecol Obstet Open Acc 9: 263. https://doi.org/10.29011/25772236.100263

Introduction

Induction of labor (IOL) is the process of stimulating uterine contractions before the spontaneous onset of labor to achieve vaginal delivery. It is a cornerstone of modern obstetric practice and is indicated when the risks of continuing pregnancy outweigh those of delivery. The rate of IOL globally has increased over the past few decades, with recent estimates placing it at 20% to 30% of all deliveries in developed countries [1]. This trend reflects both confidence in induction methods and the increased clinical indications, such as post-term pregnancies, maternal comorbidities, premature rupture of membranes, and intrauterine growth restriction.

The history of induction of labor dates to ancient times, where mechanical methods such as stripping of the membranes or the use of herbal preparations were used to achieve vaginal delivery. The discovery of Oxytocin in the mid-20th century revolutionized the induction of labor by offering a more controllable pharmacological agent. However, oxytocin was most effective only after some degree of cervical ripening has occurred. This led to the exploration of other agents that could prepare the cervix for labor, particularly in women with an unfavorable cervix, typically assessed by using the cervical score [2].

The use of prostaglandins in obstetric practice in the 1970s marked a major advancement. One of the prostaglandins, the dinoprostone (PGE2), became widely adopted for cervical ripening due to its dual action on both the cervix and the uterus [3, 4]. Over time, various formulations of dinoprostone were used, including Prostin, which comes in either a tablet or gel, and Propess, which is a sustained-release vaginal tape. Both agents have since become the standard in many labor induction protocols across the world [4, 5].

Prostin offers flexibility in dosing and has been used in hospitals where close monitoring is available [6]. Propess, introduced later, provides a controlled 10mg release of dinoprostone over 24 hours, with the advantage of a retrieval tape for quick removal in case of hyperstimulation [4]. This innovation has enhanced the ability of clinicians to tailor induction regimens with greater precision, especially in settings aimed at balancing effectiveness and maternal/fetal safety [18, 19].

In this study, we aim to evaluate the use of Prostin and Propess for the induction of labor at King Hamad University Hospital in the Kingdom of Bahrain, with a particular focus on the number of induction cycles safely administered under constant supervision and the associated maternal and fetal outcomes. While both agents are well-established for cervical ripening, the literature remains limited regarding how repeated cycles influence delivery outcomes, cesarean section rates, and postpartum and neonatal complications. By analyzing local data, this research seeks to address these gaps, provide evidence-based insight into current practice, and contribute to optimizing induction protocols in our setting.

Methods

This is a retrospective cohort analysis at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, King Hamad University Hospital in Bahrain, covering the period from January to December 2023. It included women with singleton pregnancies at or beyond 37 weeks of gestation who underwent induction of labor using either Prostin or Propess. Each cycle included either one Propess tape inserted for 24 hours or two tablets of Prostin that were inserted with a 6-hour interval between each tablet. The maximum number of cycles was three cycles; each being given to patient after full verbal and written consent was taken under close observation throughout the induction. During that period the induction cycles were three instead of two. Before starting the third cycle, each patient was counseled and reconsented for the third cycle with all outcomes explained.

Women with other methods of IOL such as those who had mechanical induction, oxytocin-only, or those who discontinued induction voluntarily prior to delivery were excluded. Data was collected from electronic medical records and included maternal demographics (age, parity, BMI, and comorbidities), induction details (type of agent used, number of cycles, and initial cervical score), and delivery outcomes (mode of delivery, use of instrumental assistance, or conversion to cesarean section). Postpartum complications, along with fetal outcomes such as Apgar scores, NICU admissions, and signs of neonatal infection, were also recorded.

Data Analysis

Statistical analysis involved descriptive statistics for baseline characteristics, while chi-square tests and Mann–Whitney U tests were used to explore associations between the number of induction cycles and clinical outcomes. Additionally, logistic regression was used to adjust for potential confounding variables, particularly the cervical score and induction agent, to assess their independent effect on delivery outcomes. All analyses used SPSS, with a p-value < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

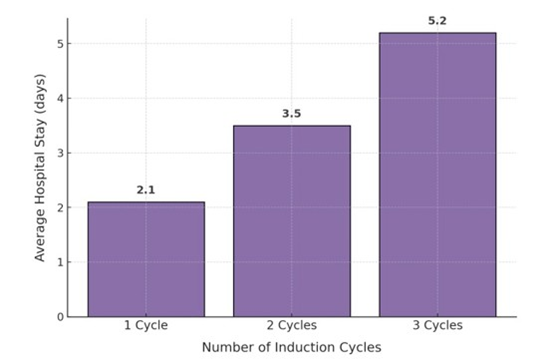

In this retrospective cohort of 278 women, age, parity, cervical status, and the number of induction cycles emerged as the principal factors influencing delivery outcomes. Primigravid women required significantly more induction cycles compared with multiparous women (p < 0.001), and each additional cycle was associated with a higher rate of cesarean delivery (p = 0.036). A higher initial cervical score was strongly correlated with successful vaginal delivery (p < 0.001), whereas an increase in the number of induction cycles was linked to a longer duration of hospital stay (p < 0.001) (Figure 1A) and reduced rate of vaginal delivery. There was no statistical significance between age and outcome of delivery. Neonatal outcomes, as assessed by 1- and 5-minute Apgar scores, along with NICU stay showed no statistical significant difference between groups.

Figure 1A: shows the average number of hospital stay increasing with the number of cycles.

These findings are consistent with current literature emphasizing parity and cervical favorability as the strongest predictors of induction success. Several recent studies have demonstrated that nulliparous women are more likely to require multiple ripening cycles and have higher cesarean section rates than multiparas, even when comparable induction methods are employed [8, 9]. The cervical score continues to serve as a strong clinical predictor of outcome; lower scores (≤ 5–6) have been associated with prolonged induction-to-delivery intervals and a higher probability of operative delivery [10, 11]. Vrouenraets et al. reported that a cervical score ≤ 5 doubled the odds for cesarean delivery following induction [10].

The present findings also support emerging evidence that repeated prostaglandin cycles confer limited additional benefits. Alojayli and Haloob (2023) found that 85.7 % of women requiring two repeat induction cycles ultimately underwent cesarean delivery [15]. Similarly, Mancarella et al. (2022) reported comparable vaginal delivery rates (approximately 62%) between secondcycle dinoprostone and oral misoprostol, indicating no advantage to repeating the same prostaglandin [14]. The RE-DINO trial further demonstrated that administering a second dinoprostone tablet after a failed initial cycle did not improve delivery outcomes compared with conversion to oxytocin [15].

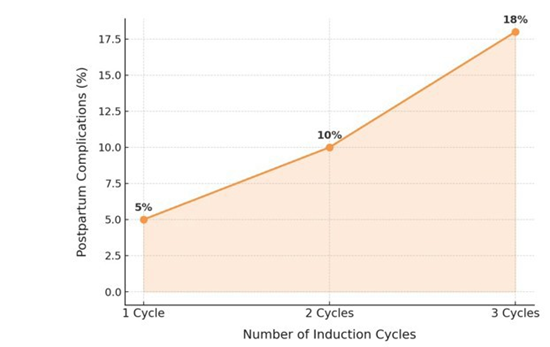

A progressive rise in postpartum complications in our study was observed with increasing number of induction cycles (Figure 1B). The most frequently encountered complications were surgical site infection, postpartum hemorrhage, puerperal pyrexia, and prolonged postnatal recovery. These findings mirror previous reports linking prolonged induction and increased cesarean rates with higher maternal morbidity, particularly infectious and hemorrhagic complications [13, 16]. Despite this, no severe neonatal morbidity or mortality was identified in the present cohort, and Apgar scores remained reassuring across all groups.

Overall, these results reinforce that parity and cervical favorability remain central to successful labor induction. Repeated prostaglandin cycles was associated with more cesarean section, pyrexia and surgical site infection without neonatal complications.

Figure 1B: shows the increase in postpartum complications with increase in number of IOL cycles.

Discussion

This study shows that parity, cervical condition, and the number of induction cycles have a clear impact on labor outcomes. However, there are currently no clear guidelines in the literature regarding the safe number of IOL cycles that can be performed, nor the potential risks associated with repeated IOL attempts. Women who required more than one induction cycle were more likely to deliver by cesarean section, stay longer in hospital, and experience a higher rate of postpartum complications. Neonatal outcomes, however, remained stable across groups. These findings reflect patterns seen in other studies that describe the influence of cervical readiness and parity on the course of induction and delivery outcomes [810].

The cervical score continues to be one of the strongest predictors of success. In this study, women with higher cervical scores were more likely to achieve vaginal delivery with a p-value of <0.001, which is consistent with reports showing that low scores are linked with longer induction times and higher cesarean rates [11, 12]. Vrouenraets and colleagues demonstrated similar results, noting that women with a cervical score of 5 or below had more than twice the risk of cesarean delivery (8). These results underline the importance of cervical assessment before and during induction, and support the use of prostaglandins for cervical ripening in women with an unfavorable cervix.

Repeated prostaglandin cycles did not appear to improve outcomes and were instead associated with higher cesarean rates. Alojayli and Haloob (2023) found that most women who needed a second cycle eventually underwent cesarean delivery [11], and Mancarella et al. (2022) reported similar vaginal delivery rates between repeated dinoprostone insertion [12]. These findings suggest that repeating the same method after an initial failure adds time and intervention without achieving vaginal delivery.

An increase in postpartum complications was also observed with additional induction cycles. The most frequent were surgical site infection (10 cases), postpartum hemorrhage (3 cases), and puerperal pyrexia (2 cases). Other studies have reported comparable results, linking prolonged induction and operative delivery with a greater risk of infection and hemorrhage [13-16]. Despite these maternal effects, neonatal outcomes remained reassuring across all groups, in keeping with research showing that when labor is monitored appropriately, induction method and duration have limited impact on short-term neonatal wellbeing [15].

These findings are in line with recommendations from NICE (NG207) and the RCOG, which advise the use of prostaglandin E₂ for cervical ripening and recommend moving to amniotomy or oxytocin once the cervix becomes favorable [16, 17]. Following a structured, stepwise approach helps limit unnecessary repeat inductions and reduce maternal risk, particularly among first-time mothers who are less likely to respond after a failed initial attempt.

Conclusion

Parity and cevical status remain key factors in the success of labor induction. Aiming to achieve vaginal delivery will not reduce cesarean section delivery, but increase hospital say, surgical site infection and postpartum hemorrhage. Therefore, prior to initiating a second cycle, as recommended by the RCOG, patients should be given a choice between having an elective cesarean section or a repeat induction cycle. As mentioned above, our limited study shows that a third cycle is not recommended.

From a clinical perspective, these results emphasize the value of careful patient selection and adherence to national guidelines. Early evaluation of induction progress and avoiding unnecessary repetition of the same method can help minimize maternal risk while maintaining safe neonatal outcomes. Continued research in larger, prospective cohorts will be useful to refine induction protocols and identify predictors of failed response that can guide more tailored obstetric care.

References

- Vogel JP, Osoti AO, Kelly AJ, Livio S, Norman JE, et al. (2017) Pharmacological and mechanical interventions for labour induction in outpatient settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 9: CD007701.

- Bishop EH (1964) Pelvic scoring for elective induction. Obstet Gynecol 24: 266–8.

- Calder AA, Embrey MP, Tait T (1977) Ripening of the cervix with extraamniotic prostaglandin E₂ in viscous gel before induction of labor. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 84: 264–8.

- Kelly AJ, Malik S, Smith L, Kavanagh J, Thomas J (2009) Vaginal prostaglandin (PGE₂ and PGF₂α) for induction of labour at term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4: CD003101.

- Ferring Pharmaceuticals (2021) Propess® 10 mg Vaginal Delivery System – Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC). Electronic Medicines Compendium (EMC).

- Hapangama DK, Neilson JP (2001) Induction of labour at term with dinoprostone (PGE₂) vaginal tablets versus controlled-release dinoprostone vaginal pessary (Propess®): a prospective observational study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 98: 183–7.

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. Practice Bulletin No. 107: Induction of Labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2009; 114: 386–97.

- Denona N (2022) Outcomes of induction of labor stratified by parity: a cohort analysis. Int J Gynecol Obstet 159: 664–9.

- Patidar BL (2022) Incidence of caesarean delivery after induction of labour in nulliparous women with poor Bishop’s score induced by dinoprostone gel. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol 11: 3156– 60.

- Vrouenraets FP, Roumen FJME, Dehing CJ, De Groot CJM (2005) The Bishop Score as a determinant of labour induction success: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 123: 203–8.

- Pevzner L, Rayburn WF, Rumney P, Wing DA (2020) Factors predicting successful labor induction with dinoprostone and misoprostol. Obstet Gynecol 136: 233–42.

- Obeidat RA, Khader YS, Abdel-Latif M (2021) Predictors of successful induction of labor in term pregnancies. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 21: 237.

- Alojayli A, Haloob R (2023) Success rate of repeated cycles of induction of labour in a UK clinical setting: a cohort study. F1000Research 12: 356.

- Mancarella D (2022) Second cycle of dinoprostone versus oral misoprostol for failed induction: a randomized comparison. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 277: 111–7.

- Coste-Mazeau P (2020) Is there an interest in repeating vaginal prostaglandin E₂ for induction of labour? Trials 21: 398.

- Tsikouras P (2022) Comparison of dinoprostone and misoprostol for induction of labour and neonatal outcomes. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 48: 905–12.

- Facchinetti F, Driul L, Vergoz L (2005) Comparison of two preparations of dinoprostone for preinduction cervical ripening. J Obstet Gynaecol 25: 313–7.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Inducing Labour. NICE Guideline NG207. 2021.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG). Induction of Labour at Term in Older Mothers (Green-top Guideline No. 70). London: RCOG; 2021.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.