Applying Population Science to Model Representative Patient Cohorts for Diabetic Kidney Disease Clinical Trials Using Real-World Data

by Andrew Bevan1*, Davide Garrisi2, Sarah Stump3, Carmichael Angeles4

1Neuroscience, PPD, part of Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cambridge, UK

2Internal Medicine, PPD, part of Thermo Fisher Scientific, Milan, Italy

3Internal Medicine, PPD, part of Thermo Fisher Scientific, Morrisville, USA

4Medical Affairs, PPD, part of Thermo Fisher Scientific, Morrisville, USA

*Corresponding author: Andrew Bevan, PPD, part of Thermo Fisher Scientific, Granta Park, Great Abington, Cambridge, CB21 6GQ, United Kingdom

Received Date: 26 November 2025

Accepted Date: 09 December 2025

Published Date: 12 December 2025

Citation: Bevan A, Garrisi D, Stump S, Angeles C (2025) Applying Population Science to Model Representative Patient Cohorts for Diabetic Kidney Disease Clinical Trials Using Real-World Data. J Diabetes Treat 10: 10152. https://doi.org/10.29011/2574-7568.010152

Abstract

Purpose: Diabetic Kidney Disease (DKD), affecting 20–40% of people with type 2 diabetes, is the leading cause of chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease. Prevalence and progression differ across demographic groups, yet US demographic data to inform FDA-recommended Diversity Action Plans remain limited. The objective was to compare demographics of DKD patients identified in a large Electronic Health Record (EHR) database with those enrolled in completed DKD trials, and to generate statistical parameters for representative clinical trial planning.

Methods: A search of TriNetX EHR data identified 583,660 US adults with ICD-10-CM code of DKD within five years, excluding ESRD. Sex, race, and ethnicity distributions were compared with nine North America–only, industry-funded DKD trials (965 participants) from Clinicaltrials.gov. Two-proportion z-tests and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests assessed demographic differences. Clopper–Pearson 95% confidence intervals defined representative ranges for hypothetical DKD trials.

Results: The EHR population was 50.2% Male, 45.4% Female; 62.8% White, 19.8% Black or African American, 4.0% Asian; and 19.7% Hispanic/Latino. Trials enrolled disproportionately more Males (64.8%), White participants (77.4%), and Hispanic/ Latino participants (35.6%), and fewer Females (35.2%) and Asian (2.0%). Significant underrepresentation was observed for Females (p < .05), Asians (p < .05), and other/unknown race (p < .01), with significant overrepresentation of White (p < .05) and Hispanic/Latino groups (p < .001). Black or African American representation was not significantly different. A 100-participant trial would be representative with: 40–60 Males, 35–55 Females, 53–72 White, 13–29 Black, 1–9 Asian, and 13–29 Hispanic/ Latino participants.

Conclusions: NA DKD trials do not reflect real-world demographics. Large EHR datasets can guide development of representative trial cohorts aligned with FDA diversity expectations.

Keywords: Diabetes; Kidney Disease; Clinical Trials; Diversity

Introduction

Diabetic Kidney Disease (DKD) is a major microvascular complication of diabetes and the leading cause of Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) and End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) worldwide. Approximately 20–40% of individuals with type 2 diabetes (T2DM) develop DKD, making it a significant contributor to global morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs [1,2]. Prevalence and progression rates differ substantially across populations, with higher risks observed among individuals of African, Asian, and Indigenous ancestry [3].

Historically, glycemic and blood pressure control—particularly through Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS) blockade—has formed the foundation of DKD management. However, recent therapeutic advances have reshaped the treatment landscape. Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors have shown 30–40% reductions in the risk of kidney failure and cardiovascular events among patients with DKD [4]. Likewise, the non-steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist finerenone has demonstrated significant renoprotective and cardioprotective benefits in large randomized controlled trials [5,6]. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists (GLP-1 RAs) are also emerging as potential agents with renal and cardiovascular benefits, particularly among individuals with elevated cardiovascular risk [7].

These developments represent a paradigm shift in DKD management, providing complementary mechanisms that address hyperglycemia, inflammation, and fibrosis. Despite these advances, the global prevalence of DKD continues to rise, highlighting the ongoing need for research to refine early detection strategies, optimize treatment combinations, and improve longterm outcomes.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has recently emphasized the importance of clinical trial populations should reflect the demographics of individuals likely to use the approved medical product [8]. Until recently, however, there was limited guidance on how to define and achieve this. Updated draft guidance released in June 2024 requires sponsors to submit Diversity Action Plans aimed at improving the representation of underrepresented populations in clinical trials [9]. The FDA recommends, where feasible, that sponsors use United States (US) disease prevalence or incidence data by demographic subgroup—sourced from published literature, epidemiologic surveys, or registries—to inform recruitment targets. However, such data is often outdated or unavailable for many conditions.

Advances in large-scale electronic health record (EHR) databases now allow for rapid analysis of demographic and clinical data across millions of US patients, identified using International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes. These Real-World Data (RWD) resources provide valuable opportunities to define the demographic characteristics of affected populations and have been successfully utilized in conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease [10] and lupus nephritis [11]. Nonetheless, as these databases are not publicly accessible, the FDA requires sponsors to justify their use and provide methodological summaries of the analyses conducted.

Recent studies have highlighted persistent underrepresentation of specific demographic groups in clinical trials [12,13]. The authors have previously reported underrepresentation of individuals of African descent in lupus nephritis trials [11]; however, this has not been examined in more common renal disorders such as DKD.

Given the FDA’s historical emphasis on clinical trial diversity planning, this study aims to compare the demographic characteristics of individuals with DKD identified through a large EHR database with those reported in completed NA-only DKD trials and to propose statistical parameters for cohort sizes to inform future DKD trial planning.

Methods

Electronic Health Records Data

The EHR data used in this study was collected on April 23, 2024 from the TriNetX Network [14], which provides access to EHRs (diagnoses, procedures, medications, laboratory values, genomic information) from approximately 150 million US patients from approximately 80 healthcare organizations (HCO). TriNetX is compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), the US federal law which protects the privacy and security of healthcare data. TriNetX is certified to the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 27001:2013 standard and maintains an information security management system (ISMS) to ensure the protection of the healthcare data it has access to and to meet the requirements of the HIPAA Security Rule. Any data displayed on the TriNetX Platform in aggregate form, or any patient-level data provided in a data set generated by the TriNetX Platform, contains only de-identified data as per the de-identification standard defined in Section §164.514(a) of the HIPAA Privacy Rule. Each participating HCO represents and warrants that it has all necessary rights, consents, approvals, and authority to provide the data to TriNetX under a Business Associate Agreement, providing their name remains anonymous as a data source and their data are utilized for research purposes. The data shared through the TriNetX Platform are attenuated to ensure that they do not include sufficient information to facilitate the determination of which HCO contributed patient information.

A database query was generated for living individuals in the United States (US) who had received ICD-10-CM diagnosis code of E11.22 T2DM with DKD in the last 5 years that had received healthcare services and did not also have an ICD-10-CM code N18.6 ESRD. Aggregate data (sex, race, ethnicity) were obtained and used to define the demographic characteristics of this DKD population.

Cohort Modelling

The sex, race and ethnicity distributions were used to define statistical parameters for hypothetical study sample sizes using the binomial (Clopper-Pearson) "exact" method to calculate the 95% confidence intervals (CI) for each demographic cohort. Due to unknown gender data in the EHR dataset, the sex distribution for the EHR dataset was based on patients with known sex.

Clinical Trials

A search of the National Institutes of Health ClinicalTrials.gov (CT.gov) database was made on April 23, 2024 for completed, industry-only funded, DKD trials of drugs or biologicals that were performed in North America (NA) and had sex and / or race or ethnicity demographic results reported in either the database or in an associated publication. The proportion of each demographic cohort (Male, Female, White, Black or African American [BAA], Asian, other/unknown race, Hispanic/Latino [HL], non-HL, unknown ethnicity) was calculated for each trial and differences to EHR distributions were evaluated by calculating a z-score for each cohort for each trial using two proportion Z-tests. The hypothesis that the median of the z-scores is zero was tested using onesample Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. Effect size was determined by Rosenthal correlation coefficients.

Results

EHR Population

As of April 23, 2024, there were 583,660 living individuals in the TriNetX EHR database in the US who had received ICD-10-CM diagnosis code of E11.22 T2DM with DKD in the last 5 years that had received healthcare services and did not also have an ICD-10CM code N18.6 ESRD. The demographic distribution was 50.2% Male, 45.4% Female and 4.4% unknown sex, 62.8% White, 19.8% BAA, 4.0% Asian and 13.4% other/unknown race, 19.7% HL, 73.5% non-HL and 6.9% unknown ethnicity (Table 1A).

A) TriNetX EHR | B) Clinical trials | |

Number of patients | 583,660 | 956 |

Gender (%) | Mean (SD) | |

Female | 45.4 | 35.2 (14.1) |

Male | 50.2 | 64.8 (14.1) |

Unknown | 4.4 | 0.0 (0.0) |

Race (%) | ||

White | 62.8 | 77.4 (14.5) |

BAA | 19.8 | 18.2 (13.0) |

Asian | 4 | 2.0 (2.2) |

Other/Unknown | 13.4 | 2.3 (1.6) |

Ethnicity (%) | ||

HL | 19.7 | 35.6 (15.4) |

Non-HL | 73.5 | 64.4 (15.4) |

Unknown | 6.9 | 0.0 (0.0) |

Abbreviations (BAA) Black or African American, (HL) Hispanic or Latino, (SD) Standard Deviation | ||

Table 1: Demographic distribution of DKD patients in A) TriNetX EHR, and B) completed US-only DKD trials.

DKD Clinical Trials

The search of CT.gov returned nine completed NA-only, industryfunded DKD trials of drugs or biologicals (965 subjects (M = 106, SD = 89) (Table 1B). Sex was reported for all nine trials, the distribution was 64.8% Male and 35.2% Female. Race was reported for six trials (813 subjects [M = 136, SD = 112], the distribution was 77.4% White, 18.2% BAA, 2.0% Asian and 2.3% other/unknown race. Ethnicity was reported for three trials (549 subjects [M = 183, SD = 113]); the distribution was 35.6% HL, 64.4% non-HL.

Comparative Analysis

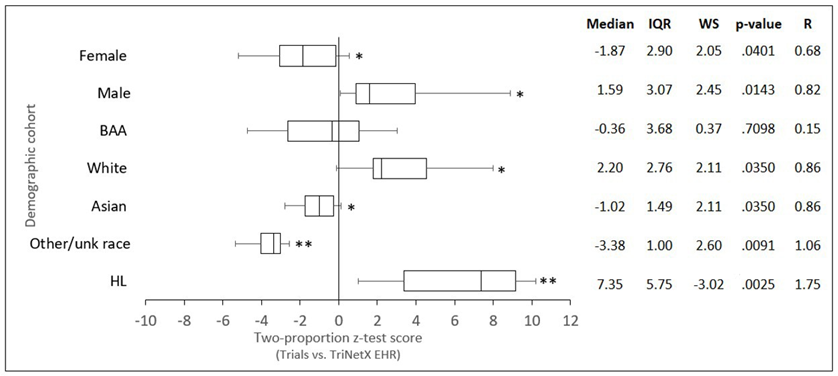

The comparison of demographic cohort proportions from DKD trials vs EHR is provided in (Figure 1). A comparison of z-scores from two proportion z-tests using one-sample Wilcoxon Signedrank tests revealed a statistically significant underrepresentation of Females in trials compared to EHR-derived data (Mdn [IQR] = -1.87 [2.90], ws = 2.05, p <.05, r = 0.68). White populations were significantly overrepresented (Mdn [IQR] = 2.20 [2.67], ws = 2.11, p <.05, r = 0.86). Whereas Asian populations were significantly underrepresented (Mdn [IQR] = -1.02 [1.49], ws = 2.11, p <.05, r = 0.86) as were patients of other/unknown race (Mdn [IQR] = -3.38 [1.00], ws = 2.60, p <.01, r = 1.06). BAA populations were not significantly underrepresented in US trials (Mdn [IQR] = -0.36 [3.68], ws = 0.37, p >.1, r = 0.15). There was a highly significant overrepresentation of HL populations in clinical trials compared to the EHR-derived dataset (Mdn [IQR] = 7.35 [5.75], ws = -3.02, p >.001, r = 1.75).

Figure 1: Comparison of demographic cohorts from completed US-only DKD clinical trials vs DKD patients in the TriNetX EHR database. Box and whisker plots were generated from z-scores calculated using two proportion z-tests. The lefthand boundary of the box indicates the 25th percentile; the righthand boundary of the box indicates the 75th percentile; the black line within the box marks the median z-score. Righthand and lefthand whiskers indicate the 90th and 10th percentiles respectively. Differences in z-scores from zero were tested using one-sample Wilcoxon signed-rank tests (* p < .05; **p < .01). Abbreviations (BAA) Black or African American, (HL) Hispanic or Latino, (IQR) interquartile range, (R) Rosenthal correlation coefficient, (WS) Wilcoxon standardized test statistic.

Cohort Modelling

The EHR-derived data were used to calculate the predicted proportion, and statistically representative range, for each demographic cohort for hypothetical US DKD trials of one hundred subjects and three hundred subjects. Based on an analysis of binomial confidence intervals, the hypothetical trial of one hundred subjects would be statistically representative (p < .05) of the EHR-derived DKD population if it included a range of 40-60 Male, 35-55 Female, 53-72 White, 13-29 BAA, 1-9 Asian and 13-29 HL patients (Table 2A). The cohort model for a hypothetical US DKD trial of three hundred subjects is presented in (Table 2B). The ranges are proportionally narrower than the 100-subject model as the confidence intervals are non-linear and inversely proportional to the square root of the sample size.

|

A) 100 patients N (range*) |

B) 300 patients N (range*) |

|

|

Female |

45 (35-55) |

136 (119-153) |

|

Male |

50 (40-60) |

151 (134-168) |

|

Other/unk sex |

4 (2-11) |

13 (7-22) |

|

White |

63 (53-72) |

188 (171-204) |

|

BAA |

20 (13-29) |

59 (46-74) |

|

Asian |

4 (1-9) |

12 (6-21) |

|

Other/unk race |

13 (7-21) |

40 (29-53) |

|

HL |

20 (13-29) |

59 (46-74) |

|

Non-HL |

74 (64-82) |

221 (205-236) |

|

Unk ethnicity |

7 (3-13) |

21 (13-32) |

|

Ranges represent 95% binomial confidence intervals. Abbreviations (BAA) Black or African American, (HL) Hispanic or Latino, (SD) standard deviation (unk) unknown. |

||

Table 2: Clinical trial cohort models for A) hypothetical n=100 patient trial B) n= 300 patient trial.

Discussion

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to assess the proportional representation of sex, race, and ethnic subpopulations in completed clinical trials of DKD and to provide statistical parameters for proportional representation based on the demographic distribution of DKD patients identified from an EHR dataset. Large EHR databases offer a valuable means of determining real-world demographics to guide the planning of more representative clinical trial cohorts. However, the FDA’s stated preference is for sponsors to use publicly available, published data sources whenever possible. This approach is feasible if such data exists and is current, but in the authors’ experience, such information is often limited. The United States Renal Data System, funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease, reports data for diabetes-related CKD, but incidence rates for DKD across sex, race, and ethnicity are not readily available. There remains a paucity of populationbased studies describing the epidemiology of DKD. In contrast, EHR-derived demographic data can be obtained in near real-time and updated regularly for any condition identifiable by ICD-10CM codes. Nevertheless, EHR data are not publicly accessible, and therefore sponsors using this approach must provide a clear rationale, a summary of the analytical methods employed, and appropriate citations for the data sources in their Diversity Action Plans, as stipulated by FDA guidance. Additionally, the case definition for DKD in this analysis was based on ICD-10-CM diagnostic codes. While practical, this approach may not perfectly align with clinically defined trial populations and could be affected by coding variability across institutions [15].

A major finding of the comparison between completed DKD clinical trials and EHR-derived data was a significant underrepresentation of females in clinical trials relative to the EHR-derived DKD population. Sex-related differences in DKD are well recognized but remain incompletely understood. Women have been shown to have an increased prevalence of advanced DKD and common DKD risk factors compared to men [16], and although women appear less likely to develop early, albuminuric DKD, they may have a higher prevalence of advanced eGFR-decline phenotypes [17]. Once DKD is established, the typical female cardioprotective advantage diminishes-women with diabetes exhibit approximately 30% greater excess cardiovascular mortality than men [18,19]. Some studies suggest higher mortality among younger women with DKD [20], while others report faster progression to kidney failure in men [19]. Hormonal factors, particularly estrogen deficiency after menopause, are thought to contribute to these differences [20]. The underrepresentation of women in clinical trials limits understanding of sex-specific responses to therapy and may contribute to less effective treatment strategies for female patients.

The second notable finding was the significant underrepresentation of Asian participants in DKD clinical trials compared to EHRderived data. DKD exhibits considerable heterogeneity across racial and ethnic groups, particularly among Asian populations. Asians tend to develop DKD at younger ages and lower BMI compared with White populations, with East Asians more often presenting with non-proteinuric, reduced eGFR phenotypes, whereas South Asians more commonly exhibit proteinuric DKD [21]. Disease progression may be faster among Asians, particularly in the setting of uncontrolled hypertension. Cardiovascular risk patterns also vary, with South Asians experience earlier and more severe coronary events [22]. Recognizing race- and ethnicityspecific differences is therefore critical for early detection, risk stratification, and tailored management. These findings emphasize the importance of aligning clinical trial enrollment with disease epidemiology and real-world demographic data to ensure that evaluations of drug safety and efficacy reflect the variety of DKD phenotypes.

Given concerns regarding the underrepresentation of BAA and HL participants in clinical trials, our finding that the proportion of BAA participants in DKD trials did not differ significantly from the EHR-derived DKD population was unexpected. Even more surprising was that HL representation in clinical trials was approximately seven-fold higher than in the EHR dataset. This may reflect increased efforts by sponsors and investigators to recruit participants from these groups, or alternatively, differences in how race and ethnicity are collected and reported between clinical trials and EHR systems. Furthermore, only three of the ten trials reviewed reported ethnicity data, resulting in a limited dataset that may not accurately represent the true HL trial population.

Ensuring that clinical trial populations reflect the realworld demographics of patients who will ultimately use new therapeutic products is a key principle of ethical and effective drug development. This is reinforced by the FDA’s recent draft guidance on Diversity Action Plans for clinical trials. Such considerations are particularly important for conditions like DKD, which disproportionately affect specific demographic groups. RWD can be used to inform representative enrollment goals, but the choice of data source must be balanced against the FDA’s preference for publicly accessible datasets, the availability of such data for the disease in question, and their contemporaneity and representativeness. These challenges can be effectively addressed using large EHR databases, provided that the rationale for their use and the supporting analytical framework is transparently communicated to the FDA.

Conclusion

In this study, we compared the demographic characteristics of more than 580,000 individuals with DKD identified through a large EHR database with those enrolled in completed NA-only DKD clinical trials. Our results show that DKD trials do not fully reflect real-world demographics, with Female and Asian participants underrepresented and White and HL participants overrepresented, while BAA representation was generally consistent with EHR data. By leveraging large-scale EHR datasets, we defined statistically representative enrollment ranges that can guide future trial design and support FDA Diversity Action Plans. Incorporating realworld demographic data into trial planning is essential to ensure representative populations, generate generalizable evidence, evaluate treatment effects across diverse groups, and ultimately promote equitable care for patients with DKD.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank PPD, part of Thermo Fisher Scientific for supporting this study.

Ethical Guidelines

This retrospective study used only de-identified aggregated patient data per the de-identification standard defined in Section §164.514(a) of the HIPAA Privacy Rule and therefore was exempt from Institutional Review Board Approval.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Thomas MC, Brownlee M, Susztak K, Sharma K, Jandeleit-Dahm KA, et al. (2015) Diabetic kidney disease. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 1: 1-20.

- Koye DN, Magliano DJ, Nelson RG, Pavkov ME (2018) The global epidemiology of diabetes and kidney disease. Advances in Chronic Kidney Disease 25: 121-132.

- Alicic RZ, Rooney MT, Tuttle KR (2017) Diabetic kidney disease: challenges, progress, and possibilities. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 12: 2032-2045.

- Kaze AD, Zhuo M, Kim SC, Patorno E, Paik JM (2022) Association of SGLT2 inhibitors with cardiovascular, kidney, and safety outcomes among patients with diabetic kidney disease: a meta-analysis. Cardiovascular Diabetology 21: 47.

- Bakris GL, Agarwal R, Anker SD, Pitt B, Ruilope LM, et al. (2020) Effect of finerenone on chronic kidney disease outcomes in type 2 diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine 383: 2219–2229.

- Agarwal R, Filippatos G, Pitt B, Anker SD, Rossing P, et al. (2022) Cardiovascular and kidney outcomes with finerenone in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease: the FIDELITY pooled analysis. European Heart Journal 43: 474-484.

- Mann JF, Ørsted DD, Brown-Frandsen K, Marso SP, Poulter NR, et al. (2017) Liraglutide and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine 377: 839-848.

- Food and Drug Administration (2020) Enhancing the diversity of clinical trial populations – eligibility criteria, enrollment practices, and trial designs: guidance for industry.

- Food and Drug Administration (2024) Diversity action plans to improve enrollment of participants from underrepresented populations in clinical studies: guidance for industry (draft guidance).

- Peroutka SJ (2022) Defining demographic cohorts in clinical trial populations using large electronic health records databases. Contemporary Clinical Trials 121: 106890.

- Bevan A, Garrisi D, Stump S. et al. (2024) Using a large electronic health record database to define representative patient populations for lupus nephritis trials (abstract). American Journal of Kidney Diseases 83: S153.

- Striving for diversity in research studies (editorial) (2021) New England Journal of Medicine 385: 1429-1430.

- Tanne JH (2022) US must urgently correct ethnic and racial disparities in clinical trials, says report. BMJ 377: o1292.

- TriNetX website.

- Guo LL, Morse KE, Aftandilian C, Steinberg E, Fries J, et al. (2024) Characterizing the limitations of using diagnosis codes in the context of machine learning for healthcare. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 24: 51.

- Yu MK, Lyles CR, Bent-Shaw LA, Young BA, Pathways Authors (2012) Risk factor, age and sex differences in chronic kidney disease prevalence in a diabetic cohort: the pathways study. American Journal of Nephrology 36: 245–251.

- Giandalia A, Giuffrida AE, Gembillo G, Cucinotta D, Squadrito G, et al. (2021) Gender differences in diabetic kidney disease: focus on hormonal, genetic and clinical factors. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22: 5808.

- Peters SA, Huxley RR, Sattar N, Woodward M (2015) Sex differences in the excess risk of cardiovascular diseases associated with type 2 diabetes: potential explanations and clinical implications. Current Cardiovascular Risk Reports 9: 36.

- Balafa O, Fernandez-Fernandez B, Ortiz A, Dounousi E, Ekart R, et al. (2024) Sex disparities in mortality and cardiovascular outcomes in chronic kidney disease. Clinical Kidney Journal 17: sfae044.

- Jafar TH, Seng LL, Wang Y, Lim CW, Chan CM, et al. (2024) Heterogeneity by age and gender in the association of kidney function with mortality among patients with diabetes—analysis of diabetes registry in Singapore. BMC Nephrology 25: 23.

- Bhalla V, Zhao B, Azar KM, Wang EJ, Choi S, et al. (2013) Racial/ ethnic differences in the prevalence of proteinuric and nonproteinuric diabetic kidney disease. Diabetes Care 36: 1215-1221.

- Hanif W, Susarla R (2018) Diabetes and cardiovascular risk in UK South Asians: an overview. British Journal of Cardiology 25: S8-S13.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.