Angiosarcoma of the Small Intestine in HIV Patient: A Case Report and Literature Review

by Musili Kafaru1, Bharti Sharma2,3*, Tiangui Huang4, GeorgeA griantonis2,3, Jennifer Whittington2,3, Zahra Shafaee2,3

1St. George’s University School of Medicine, West Indies, Grenada

2Department of Surgery, NYC Health + Hospitals/Elmhurst, Queens, New York, USA

3Department of Surgery, Icahn School of Medicine at The Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, USA

4Department of Pathology, Elmhurst Hospital Center, New York, USA

*Corresponding author: Bharti Sharma, Department of Surgery, NYC Health + Hospitals/Elmhurst, Queens, New York, USA

Received Date: 29 August 2024

Accepted Date: 04 September 2024

Published Date: 06 September 2024

Citation: Kafaru M, Sharma B, Huang T, Agriantonis G, Whittington J, et al. (2024) Angiosarcoma of the Small Intestine in Hiv Patient: A Case Report and Literature Review. J Surg 9: 11134 https://doi.org/10.29011/2575-9760.11134

Abstract

Angiosarcoma is a highly aggressive soft tissue sarcoma that develops from the endothelial lining of the blood vessels. It is a rare malignant tumor that mostly affects the skin and subcutaneous tissue. Angiosarcoma rarely occurs in the Gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and the prognosis is poor when it does. There have been a few reported cases of primary intestinal angiosarcoma; however, no case of angiosarcoma of the GI tract in a Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) patient has been identified. We present the first reported case of primary small bowel angiosarcoma in a 32-year-old male with HIV and chronic slow-growing mesenteric mass, for which the patient underwent surgical en-bloc resection with evidence of local invasion to the sigmoid colon and bladder. Pathological and immunohistochemical analyses confirmed the diagnosis of angiosarcoma. We discuss the surgical intervention, further postoperative management, and clinical course. In this article, we also analyzed reported cases of primary small intestinal angiosarcoma. We discovered that factors such as old age, postoperative GI bleeding, metastasis, and a lack of chemotherapy are associated with a poorer prognosis. Notably, the actual tumor size or the patient’s sex has no impact on patient outcome. This case highlights the importance of recognizing this rare malignancy and its grim prognosis in the context of HIV.

Introduction

Angiosarcoma is an uncommon, malignant soft tissue sarcoma arising from the vascular or lymphatic endothelium. Despite its rarity, it is highly aggressive, with a propensity to invade and metastasize to other parts of the body due to the extensive distribution of blood vessels and lymphatic systems [1]. Angiosarcoma, which accounts for fewer than 2% of all soft tissue sarcomas, usually affects the skin and subcutaneous tissue. It is more prevalent in men and the elderly, with a median age of 68.5 years [1,2]. The specific cause of angiosarcoma is unknown; however, certain risk factors, including chemical exposure, radiation therapy history, and chronic lymphedema, have been associated with its development [3]. Intestinal angiosarcomas are highly rare and present with nonspecific symptoms such as anemia, GI bleeding, abdominal pain, fatigue, and weight loss. The rarity and atypical presentation often result in a delayed diagnosis and a poor prognosis [4]. We present the first reported case of intestinal angiosarcoma in a young man with HIV whose HIV status has been well-controlled since starting antiretroviral medication after diagnosis in 2019. This case is noteworthy because Kaposi sarcoma commonly affects immunocompromised individuals, particularly those with HIV, and the GI tract is the second most common site [5]. Other GI malignancies seen in these patients include Epstein-Barr virus-associated smooth muscle tumors, posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders, and lymphomas [5,6]. We also analyzed literature reviews on primary small intestinal angiosarcoma to better understand its clinical presentation, diagnosis challenges, therapeutic methods, and outcomes.

Case Presentation

A 32-year-old Hispanic male with past medical history of HIV (since 04/2019) on antiretroviral therapy (HIV viral load – HIV-1 RNA detected <20 with a CD4 count of 975 cells/mcL) and history of mesenteric mass in pelvis (since 01/2020), who has been evaluated with plans for surgical resection but refused surgical intervention, presented to the emergency department with complain of fatigue, shortness of breath, dizziness, and mild headache for one week. The patient also reported blood in stool and occasional black stool for two months. Before presentation, he was seen in the clinic by his primary care doctor who referred him to the Emergency Department (ED) for a blood transfusion due to severe anemia with a hemoglobin of 5mg/dl. He was a former cigarette smoker and drank alcohol socially. The patient denied a history of radiation therapy or toxic chemical exposure. Family history was positive for malignant tumors.

Family history:

Paternal grandfather: stomach cancer

Paternal grandmother: uterine cancer

Maternal aunt: uterine cancer

Paternal uncle: colonic polyps

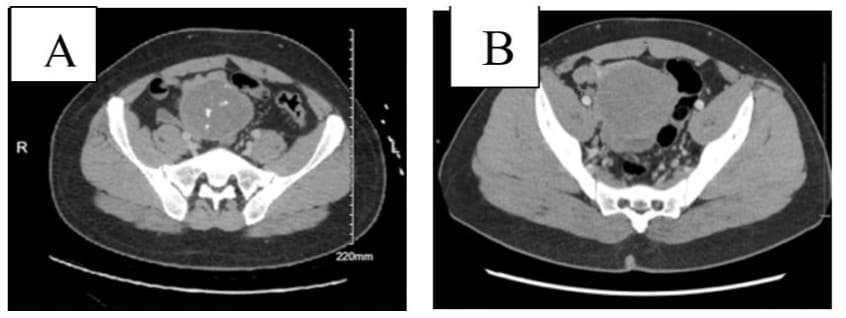

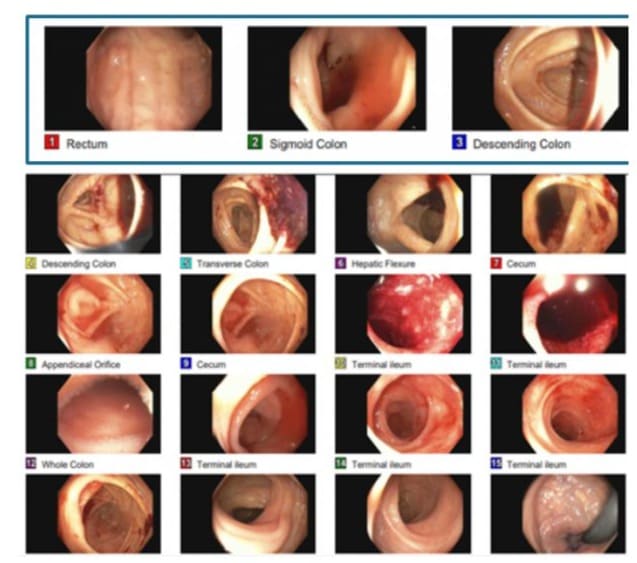

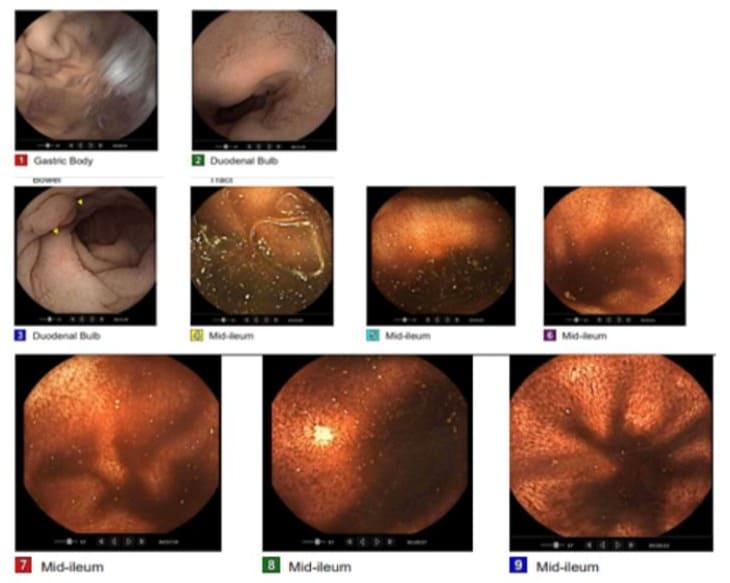

Paternal aunt: breast cancer

Clinical evaluation was notable for tachycardia, abdomen was soft without tenderness or palpable mass. Laboratory analysis revealed a normal white blood cell count. Hemoglobin and hematocrit were significantly low with a value of 5/17.1 g/dL for which the patient received two units of packed red blood cells and responded well. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed a single sessile polyp in the gastric body and the first portion of the duodenum with no bleeding. A contrast-enhanced Computed Tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed a decrease in size of the complex mesenteric mass adjacent to the dome of the bladder now measuring 7.8 x 6.6 x 6.5 cm (Figure 1A). CT scan a year ago revealed a large complex heterogeneous soft tissue mass with solid and cystic components and calcifications superior to the bladder and between the bladder and the bowel measuring 8.5 x 6.7 x 7.6 cm (Figure 1B). On colonoscopy, there was clotted blood in the entire colon and red blood in the ileum 20 cm from the ileocecal valve. No actively bleeding lesions were identified (Figure 2). Capsule endoscopy was further performed to identify the source of the GI bleeding (Figure 3). Due to ongoing bleeding on capsule endoscopy, the patient was taken to the operating room for diagnostic laparoscopy, and converted to exploratory laparotomy. The mass was arising from the small bowel. It was adherent to the bladder wall and sigmoid colon requiring en-bloc resection of the small bowel, bladder wall, and sigmoid colon, with small bowel anastomosis and colonic anastomosis with primary repair of the bladder. The patient did well post-operatively and was discharged home on postoperative day 5.

Figure 1: Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis (06/2024) of a 32-year-old-man with anemia, showing (A) a slight decrease of the complex mesenteric mass from maximum 8.2 cm diameter to 7.8 cm diameter, and (B) CT scan a year ago (01/2023) showed large complex heterogenous mass superior to the bladder and between the bladder and the bowel measuring 8.5 x 6.7 x 7.6 cm.

Figure 2: Colonoscopy revealing clotted blood in the entire colon and blood in the ileum.

Figure 3: Video capsule endoscopyshowed a medium-sized (between 5-20 mm) sessile polyp found in the duodenum without active bleeding. Red blood is found in the ileum. Active ongoing bleeding in the small bowel.

Pathological Findings

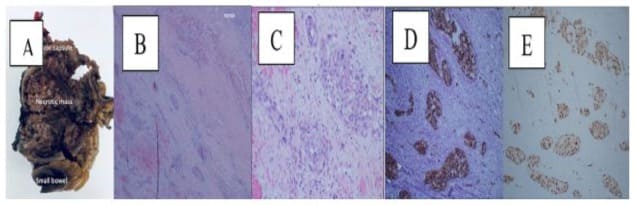

The friable mass was identified at the mesenteric aspect of the small bowel, measuring 9.0 x 7.0 x 7.0 cm (Figure 4). Microscopic examination (Figure 5 A-C) showed angiosarcoma at the serosal aspect of the small bowel with fibrotic capsule. There was extensive necrosis and only foci of viable sarcoma cells. Foreign body material and giant cell reaction seen. Small bowel mucosa was unremarkable. The margins were negative for sarcoma. The cells are maintained in the vascular spaces highlighted by CD34. The neoplastic cells are positive for CD31, ERG 1, CAM 5.2, cytokeratin AE1/E3 (very weak), negative for CK7, CD34, and MSA on immunohistochemistry analysis ((Figure 5 D-E). Ki-67 30%. HHV8 is negative.

Figure 4: intraoperative finding revealed a small bowel segment with a thick capsule and necrotic tissue.

Figure 5: Pathological findings. (A) gross examination of resected tumor; (B) tumor necrosis. Immunohistochemical analysis of the tumor tissue showing, (D) positive for CD31 and (E) ERG.

Management and Outcome

To analyze the management and outcomes of patients with primary intestinal angiosarcoma, we searched PubMed using the search term “primary small intestinal angiosarcoma” from 2012 to 2024. We found 11 case reports but excluded 4 because they were not located in the small intestine, leaving us to analyze 7 cases [1,2,7,3,4,8,9]. Our analysis revealed that surgical resection is the primary treatment for intestinal angiosarcoma, often combined with adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation therapy. Of the 7 cases reviewed, 6 patients underwent surgical resection. Two of the patients with resection received adjuvant chemotherapy with paclitaxel, while one experienced an allergic reaction and was switched to doxorubicin. Due to financial constraints, the remaining four patients either refused chemotherapy or died before they could attempt it. One of the patients who received surgical resection and adjuvant treatment died in less than a month from malignant bloody ascites that necessitated repeated blood transfusions [7], and the other died in less than a year from rapid disease progression with cancer pain [3]. The survival period for the four patients who received surgical resection without subsequent chemotherapy was notably short, with survival rates of fewer than six months reported [2,7,4,9]. In our case report, the patient underwent a successful surgical resection without postoperative complications. The patient was presented at the tumor board meeting, where adjuvant radiation therapy was recommended due to the proximity of the tumor bed to the pelvic side wall and the need for dissection of this tumor from the pelvic side wall. A genetic referral was made given the patient’s young age and strong family history of cancer. However, on post-discharge day 42, the patient presented to the emergency room with progressive hemoptysis, weight loss, and diaphoresis for the past week. CT Angiography (CTA), thoracentesis, and bronchoscopy with lung tissue biopsy confirm stage IV angiosarcoma with pulmonary metastasis. The patient is currently undergoing palliative chemotherapy discussion.

Discussion

Angiosarcoma, originating from the vascular or lymphatic endothelium, is a rare but very aggressive tumor with a high potential for metastasis due to its vast vascular and lymphatic networks [1]. It accounts for less than 2% of all soft tissue sarcomas and primarily affects the skin and subcutaneous tissue, with rare occurrences in the small intestine [2]. Langhans and colleagues first documented angiosarcoma in the spleen in 1879, and since then, there have only been a few reported cases of primary intestinal angiosarcoma [7]. Commonly involved organs include the heart, liver, and spleen [10]; it frequently metastasizes to the lung [11]. Due to delays in presentation and diagnosis, intestinal angiosarcomas have a poor prognosis. Our literature review of 7 cases of primary small bowel angiosarcoma reveals that patients often present with nonspecific symptoms of abdominal pain, abdominal distention, fatigue, weight loss, anemia, and bloody stool [1,2,7,3,4,8,9]. Notably, none of the reviewed patients, including our own, had a history of radiation exposure or chemical exposure. Imaging modalities like CT scans and endoscopies are frequently insufficient for diagnosing intestinal angiosarcomas because of their lack of specificity[4]. Harding et al. further support this by finding that CT scans, capsule endoscopy, Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), and Positron Emission Tomography (PET) are insufficient to detect bleeding sites or diagnose the disease [9].In our case, while CT scans identified the abdominal mass, capsule endoscopy revealed active bleeding but did not confirm the diagnosis. We achieved a definitive diagnosis through surgical resection and immunohistochemical analysis [4], which revealed positivity for endothelial markers such as CD 31, ERG 1, and CAM 5.2, consistent with other cases of intestinal angiosarcoma.

Treatment modalities mainly involve surgical resection, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy [4]. The decision to use radiotherapy as an initial treatment or after resection is based on the location of the tumor, size, overall health of the patient, or unresectable tumor. Sasaki et al. discovered that Radiotherapy (RT), combined with or without surgery and adjuvant rIL-2 immunotherapy improved survival in people with angiosarcoma. However, there isn’t a lot of information specifically on intestinal angiosarcoma [11,12]. All adjuvant chemotherapies are based on empirical studies of cutaneous angiosarcoma, as studies on GI angiosarcoma are scarce due to their rarity [9]. Common chemotherapy options include doxorubicin, paclitaxel, thalidomide, vincristine, and dacarbazine. Doxorubicin and paclitaxel provide longer survival. Due to the tumor’s proximity to the pelvic side wall, we recommended adjuvant radiation therapy for our patient after surgical resection. The patient developed hemoptysis, diaphoresis, and weight loss a few weeks after surgery, leading to hospital admission. The CTA showed diffuse, scattered ground-glass and nodular infiltrates throughout the lungs, with increasing mediastinal and hilar adenopathy. A thoracentesis and bronchoscopy confirmed that the angiosarcoma had metastasized, and the tumor was positive for CD31 (diffuse), CD34 (rare), and von Willebrand Factor (partial). We recommended palliative chemotherapy, choosing Adriamycinbased vs Taxane-based. The patient opted to go for a second opinion before finalizing his decision to proceed with chemotherapy. This case highlights the challenges of diagnosing and managing small bowel angiosarcoma, especially in patients with HIV. The singlepatient nature of this case may not fully represent the broader spectrum of the disease, and there is a lack of long-term follow-up data to assess outcomes and recurrence. Because this cancer shows up in a very unusual way, we must think about intestinal tumors, like angiosarcoma, in all patients who have ongoing GI symptoms like abdominal pain and bleeding from the rectum. We should start the workup earlier to find it early and improve patient outcomes. (Table 1) summarizes the literature on previously reported cases of primary small intestinal angiosarcoma, including our patients.

Table 1: It represents previously reported cases of primary small intestinal angiosarcoma, including our patients. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of primary small intestinal angiosarcoma in a well-controlled HIVpositive patient. We also examined the clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of seven reported cases of intestinal angiosarcoma. We discovered that it is most common in men and the elderly, with the most common presentation being abdominal pain, fatigue, weight loss, and rectal bleeding. The primary treatment is surgical resection, with or without adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation therapy. According to reports, the addition of adjuvant chemotherapy improves the patient’s prognosis. Our case report is limited by the small size of the literature review and the singlepatient nature.

References

- Nai Q, Ansari M, Liu J, Razjouyan H, Pak S, et al. (2018) Primary small intestinal angiosarcoma: epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Clinical Medicine Research 10: 294-301.

- Ma X, Yang B, Yang Y, Wu G, Li Y, et al. (2023) Small intestinal angiosarcoma on clinical presentation, diagnosis, management, and prognosis: A case report and review of the literature. World Journal of Gastroenterology 29: 561-578.

- Tamura K, Matsuda K, Ito D, Sakanaka T, Tamiya M, et al. (2022) Successful endoscopic diagnosis of angiosarcoma of the small intestine: A case report. DEN Open 2: e24.

- Liu Z, Yu J, Xu Z, Dong Z, Suo J (2019) Primary angiosarcoma of the small intestine metastatic to peritoneum with intestinal perforation: a case report and review of the literature. Translational Cancer Research 8: 1635-1640.

- Ho-Yen C, Chang F, van der Walt J, Lucas S (2007) Gastrointestinal malignancies in HIV-infected or immunosuppressed patients: pathologic features and review of the literature. Advanced in Anatomic Pathology. 14:431-443.

- Persson EC, Shiels MS, Dawsey SM, Bhatia K, Anderson LA, Engels EA (2012) Increased risk of stomach and esophageal malignancies in people with AIDS. Gastroenterology 143: 943-950.e2.

- Ni Q, Shang D, Peng H, Roy M, Liang G, et al. (2013) Primary angiosarcoma of the small intestine with metastasis to the liver: a case report and review of the literature. World Journal Surgical Oncology 11: 242.

- Takahashi M, Ohara M, Kimura N, Domen H, Yamabuki T, et al. (2014) Giant primary angiosarcoma of the small intestine showing severe sepsis. World Journal Gastroenterology 20: 16359-16363.

- Fohrding LZ, Macher A, Braunstein S, Knoefel WT, Topp SA (2012). Small intestine bleeding due to multifocal angiosarcoma. World Journal of Gastroenterology 18: 6494-6500.

- Siderits R, Poblete F, Saraiya B, Rimmer C, Hazra A, et al (2012) Angiosarcoma of small bowel presenting with obstruction: novel observations on a rare diagnostic entity with unique clinical presentation. Gastrointestinal Medicine 2012: 480135.

- Sasaki R, Soejima T, Kishi K, Imajo Y, Hirota S, et al. (2002) Angiosarcoma treated with radiotherapy: impact of tumor type and size on outcome. 52: 1032-1040.

- Li R, Ouyang Z, Xiao J, He J, Zhou Y, et al. (2017) Clinical characteristics and prognostic factors of small intestine angiosarcoma: a retrospective clinical analysis of 66 cases. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry 44: 817-827.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.