Anaerostipes caccae CLB101™, a Novel Probiotic and Key Butyrate Producer, Aids in the Resolution of Long-Term Food Intolerances in a Patient in 12 Weeks: A Case Report

by Oscar Coetzee1,2*, Danielle Arnold3

1Professor, Notre Dame University of Maryland, Baltimore, Maryland, USA

2Associate Adjunct Professor, Georgetown University, Washington, District of Columbia, USA

3Instructor, Purdue Global University, Lafayette, Indiana, USA

*Corresponding author: Oscar Coetzee, Professor, Notre Dame University of Maryland, Baltimore, Maryland, USA and Associate Adjunct Professor, Georgetown University, Washington, District of Columbia, USA

Received Date: 16 January 2026

Accepted Date: 21 January 2026

Published Date: 23 January 2026

Citation: Coetzee O, Arnold D. (2026). Anaerostipes caccae CLB101™, a Novel Probiotic and Key Butyrate Producer, Aids in the Resolution of Long-Term Food Intolerances in a Patient in 12 Weeks: A Case Report. Ann Case Report. 11: 2510. https://doi.org/10.29011/25747754.102510

Abstract

The imbalances in the microbiome have recently been associated as a potential key component in food aversions, like allergies, intolerances and sensitivities. With microbiota representing between 70% to 90% of cells and 99% of genes in and on human bodies, it is compelling to consider that microbiomes play a role in food allergies and our overall biology. Factors like low fibre diets, processed foods, non-vaginal birth, non-breastfeeding, lack in exposure to farm animals and pets, older siblings, long-term antibiotic use, longterm antacid use, herbicides, pesticides, and other environmental and epidemiologic factors that influence microbial exposures have been linked to food allergy/sensitivity risk. There are very few long-term solutions to food sensitivities, intolerances, and/or allergies and endless people suffer mild to severe symptoms and side effects daily. The permanent solution might not be in temporary food elimination, or basic digestive support, but rather the replenishment of some key anaerobic strains to establish more butyrate. Butyrate has come to the forefront recently through literature in playing a significant role in the overall gut and digestive health. This case report reviews a 47-year-old female with long-term food intolerances, taking a novel butyrate-producing probiotic for 12 weeks with improvements not only in symptoms, but also increases in the key anaerobic strains Akkermansia, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, and Roseburia. In addition, dramatic improvements were observed in opportunistic and histamine/LPS producing bacteria Morganella and Prevotella. The patient was able to tolerate foods with no side effects for the first time in years since taking this probiotic strain.

Keywords: Probiotic; Anaerobes; Keystone Commensals; Food Intolerances; Food Allergies; Food Sensitivities; Microbiome; Tight Junctions; Anaerostipes Caccae; Permeability, LPS Lipopolysaccharides.

Introduction

Food sensitivities, allergies, and intolerances are a common and growing issue in modern society. Approximately 33 million individuals suffer from food allergies in the United States, affecting an estimated 6.2% of adults and 5.8% of children, with up to 24% of American households reporting a combination of food intolerances, allergies, and sensitivities [1-3]. Food intolerances are generally associated with impaired digestive capacity and gastrointestinal symptoms, whereas food allergies represent acute immune-mediated reactions that can lead to anaphylaxis through IgE and mast cell activation. Food sensitivities may involve nonlife-threatening immune responses, often IgG-mediated, and present with a wide range of symptoms spanning gastrointestinal, neurological, and systemic manifestations [4]. Notably, food allergy prevalence in children increased by approximately 50% between 1997 and 2011 and rose by an additional 50% between 2007 and 2021 [5,6].

While food-related adverse reactions are frequently categorized by immune phenotype or trigger foods, emerging evidence suggests that disruptions in gut microbial ecology and metabolic function may represent a shared upstream contributor to loss of food tolerance. This case report describes a 47-year-old female with long-standing food intolerances and sensitivities who underwent a targeted intervention using a novel encapsulated anaerobic probiotic strain, Anaerostipes caccae CLB101™. Within 12 weeks of supplementation, the patient was able to consume previously reactive foods without gastrointestinal symptoms. Pre- and postintervention GI stool testing by (qPCR GI Spotlight – Diagnostic Solutions Laboratory) demonstrated notable microbiome shifts, including recovery of key anaerobic taxa such as Akkermansia muciniphila, with additional improvements in Roseburia and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii. Concurrently, severely elevated opportunistic gram-negative organisms, including Morganella spp. and Prevotella spp., normalized within the intervention period, along with previously imbalanced phyla Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes. Together, these findings may suggest that restoration of anaerobic microbial function may have contributed to the observed improvement in food tolerance and quality of life.

Narrative

Patient Information: A 47-year-old female suffering with longterm food intolerances and sensitivities, especially dairy and gluten. History of gastritis, polyps in oesophagus, and general irritable bowel issues.

Clinical Findings: Patient tried several interventions for symptom alleviation over several years, which included various elimination diets, gluten-free, dairy-free, FODMAPs, several digestive enzymes, gut protocols, and supplements, with moderate to no effect or relief.

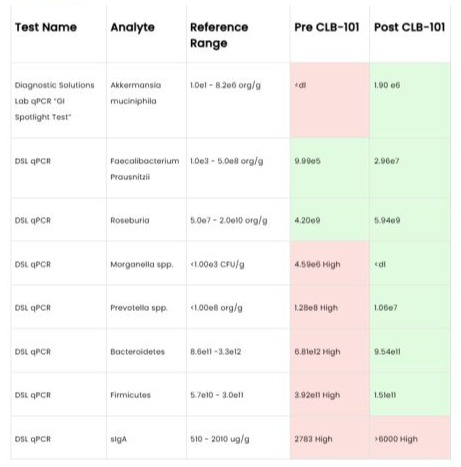

Diagnostic Assessment: Patient underwent baseline qPCR stool testing from (Designs for Health GI Spotlight™) while experiencing full symptom expression, including bloating, digestive dysfunction, and inability to tolerate dairy and gluten. Initial testing revealed suppression of multiple obligate anaerobic taxa associated with butyrate production, including Akkermansia muciniphila, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, and Roseburia spp., alongside marked elevation of opportunistic gram-negative organisms such as Morganella spp. and Prevotella spp.

Given the global reduction in anaerobic, butyrate-producing organisms, it was hypothesized that impaired microbial butyrate production and downstream effects on epithelial metabolism and barrier function may have contributed to the patient’s long-standing food intolerances. Based on this rationale, the patient-initiated supplementation with Anaerostipes Caccae CLB101™, a high butyrate-producing anaerobic strain delivered in an encapsulated probiotic format designed to survive upper gastrointestinal transit. (Weeks 1 to 8 one cap per day, weeks 9 to 12 two caps per day).

After twelve weeks of supplementation, follow-up stool testing demonstrated substantial microbiome shifts. Akkermansia muciniphila increased from below detectable limits to 1.90e6 org/g, with additional improvements observed in Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Roseburia spp. concurrently, previously elevated opportunistic gram-negative taxa, including Morganella spp. and Prevotella spp., normalized within reference ranges, and imbalances in the phyla Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes resolved. Fecal SIgA levels increased from baseline to follow-up testing.

Clinically, these microbiome changes coincided with the resolution of gastrointestinal symptoms and improved tolerance to previously reactive foods, particularly dairy, which the patient was able to reintroduce without adverse effects.

Therapeutic Intervention: Given baseline stool testing demonstrating suppression of multiple obligate anaerobic, butyrate-producing taxa, a targeted intervention was selected to restore anaerobic butyrate production in the colon. The patientinitiated supplementation with Anaerostipes caccae CLB101™, an encapsulated anaerobic probiotic strain with high butyrateproducing capacity. The encapsulated delivery format was chosen to support survival through the upper gastrointestinal tract and targeted activity within the anaerobic environment of the colon. Supplementation continued for a total of twelve weeks.

Follow-up and Outcomes: During the twelve-week supplementation period, the patient reported progressive improvement in gastrointestinal symptoms, including reduced bloating and digestive discomfort. By the end of the intervention, she was able to reintroduce previously reactive foods, particularly dairy, without gastrointestinal or systemic symptoms. Follow-up stool testing demonstrated significant microbiome shifts, including restoration of key anaerobic taxa and normalization of previously elevated opportunistic organisms. No adverse effects were reported during the intervention period, and the patient described a meaningful improvement in quality of life and dietary flexibility (Figure 1).

Diagnostics

Figure 1: Diagnosis.

Discussion

This case report describes resolution of long-standing food intolerances following targeted supplementation with an encapsulated anaerobic, high butyrate-producing strain (Anaerostipes caccae CLB101™).

At baseline, stool testing demonstrated suppression of multiple obligate anaerobic taxa associated with butyrate production, alongside the reduction of opportunistic gram-negative organisms.

The observed clinical and microbial changes following intervention support the hypothesis that impaired anaerobic butyrate metabolism may have contributed to loss of food tolerance in this patient.

Restoration of Anaerobic Butyrate-Producing Capacity

Butyrate-producing obligate anaerobes play a central role in maintaining intestinal homeostasis. Reduced abundance of these organisms has been associated with food allergies and intolerance states, potentially through impaired epithelial metabolism and immune tolerance mechanisms. Butyrate serves as the primary energy substrate for colonocytes and is critical for sustaining epithelial function and microbial ecosystem balance [7]. In this case, the widespread reduction of anaerobic, butyrate-producing bacteria at baseline suggests that an important metabolic process supporting gut health was impaired, which may help explain the patient’s long-standing food intolerance. Supplementation with Anaerostipes caccae CLB101™, selected for its high butyrateproducing capacity and targeted colonic delivery, was followed by recovery of multiple anaerobic taxa, consistent with restoration of a butyrate-supportive environment.

Barrier Integrity, Antigen Exposure, and Food Tolerance

Emerging evidence indicates that butyrate plays a key role in regulating intestinal barrier integrity by modulating tight junction protein expression and epithelial permeability. Experimental models demonstrate that butyrate upregulates tight junction components such as occludin and zonula occludens while suppressing permeability-associated claudins, thereby limiting paracellular antigen translocation [8]. In food allergy and intolerance models, reduced butyrate availability has been linked to impaired oral tolerance and heightened immune responses to dietary antigens, whereas restoration of butyrate signalling improves tolerance by reinforcing the epithelial barrier [9]. The patient’s ability to reintroduce previously reactive foods following intervention is therefore plausibly related to improved barrier function and reduced exposure of the immune system to luminal antigens.

Microbial Ecosystem Normalization and Luminal Oxygen Dynamics

In addition to its effects on barrier integrity, butyrate influences the intestinal microenvironment by promoting epithelial oxygen consumption and maintaining luminal hypoxia. Stabilization of hypoxia-inducible factor signalling by butyrate supports anaerobic conditions favourable to obligate anaerobes while limiting expansion of facultative gram-negative organisms [10]. Spatial studies of the gut microbiome demonstrate that increased oxygen availability favours Proteobacteria, whereas anaerobic conditions support butyrate-producing taxa [11]. In this case, normalization of opportunistic organisms such as Morganella spp. and Prevotella spp. may therefore reflect restoration of anaerobic luminal conditions rather than direct microbial competition.

The marked increase in Akkermansia muciniphila following intervention further supports this ecological interpretation. Akkermansia participates in mucin turnover and mucus layer maintenance and engages in cross-feeding interactions with anaerobic butyrate producers. Restoration of these syntrophic networks may contribute to renewal of the mucus barrier, limiting antigen penetration and supporting immune tolerance [9].

Limitations and Implications

As a single-patient case report, this observation cannot establish causality. Butyrate levels were not directly measured, and clinical outcomes were assessed primarily through patient report and stool-based microbial analysis. Nevertheless, the convergence of symptom resolution with coherent, mechanismaligned microbiome shifts supports a biologically plausible role for restoration of anaerobic butyrate metabolism in alleviating food intolerance. This case highlights the potential importance of targeting microbial metabolic function, rather than individual taxa alone, in patients with long-standing food intolerance and dysbiosis.

Patient Perspective

I grew up in a traditional Armenian family with home-cooked meals that included dairy and gluten. As a young adult in my early 20’s I had experienced a lot of gastrointestinal issues which included heartburn, bloating, and digestive issues. Polyps were detected in my oesophagus after an endoscopy, and I was put on PPIs for years. In 2014, I got breast implants; by 2016, I started having massive migraines after consuming dairy. Shortly after, consuming almonds, blueberries, apples, then gluten-containing foods, it seemed that my food tolerances started to get even worse. I tried many enzymes before eating foods with dairy and the only thing that seemed to give some relief was “Gluten and Dairy” enzymes. In 2022, I decided to have my breast implants removed in hopes to see improvement with food sensitivities; unfortunately, that was not the case. I tried the elimination diet, being a nutritionist, but no changes were detected. After taking Anaerostipes caccae CLB101™ almost three months ago and slowly introducing cow dairy, I was nonreactive which was mind-blowing. With that being said, I forgot to mention in my earlier statement the only dairy that I could consume at the time with zero reaction to was goat cheese. Prior interventions: elimination diet, dairy and gluten enzymes, not consuming dairy products, breast implant removal, with little to no long-lasting effect.

Background: “Anaerostipes caccae and Butyrate Metabolism”

Anaerostipes caccae (A. caccae) is a spore-forming, gram-variable, rod-shaped, non-motile species of anaerobic bacteria that are commonly found in the human gut microbiota, primarily in the lumen of the colon [12]. A. caccae is part of the Bacillota (formerly Firmicutes) phylum and is known for its role in fermenting carbohydrates, acetate, and lactate and producing the short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) butyrate [13-15]. This process is crucial for gut health, as butyrate supports intestinal barrier integrity and healthy inflammatory responses. Anaerostipes caccae CLB101™ probiotic is a live, once daily probiotic which has been preclinically shown to promote direct butyrate production in the lower gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Powered by butyrate production, this product promotes microbiome diversity, GI barrier integrity, healthy immune and inflammatory responses, and digestive health, including potentially supporting the digestion of commonly challenging foods and certain food allergens.

Anaerostipes caccae was originally isolated and designated as the type species (meaning first and defining member) of its genus Anaerostipes in 2002 [15]. It belongs to the Clostridia class, and more specifically the Clostridium coccoides group (also known as Clostridium cluster XIVa) which is known for supporting butyrate production and host immune health by promoting the development of regulatory T (T-reg) cells and immunoglobulin A (IgA)-producing cells [10,15,16]. A. caccae is an anaerobic bacterium supporting epithelial hypoxia, which is essential for maintaining a healthy gut microbial environment [17]. It is also spore-forming, which enhances its probiotic stability and viability as spores remain inert to harsh environments, including that of the GI tract, and facilitate the transit of the probiotic in order to reach the lower intestines [14].

Anaerostipes May Help Promote Direct Butyrate Production in the Lower GI Tract

Butyrate is a SCFA that plays an important role in gut health [18]. In the GI tract it is mainly synthesized in the colon from dietary carbohydrates or bacterial metabolites, such as lactate and acetate, by anaerobic commensal bacteria belonging to the Clostridium clusters IV and XIVa [18]. A. caccae is primarily found in the lumen of the lower GI tract, especially the colon, where it thrives in the anaerobic, fibre-rich environment and contributes to the production of butyrate [12,13]. Butyrate targeted to the lower GI tract (bypassing the upper intestines where it could otherwise be absorbed too early to support colon health) has been shown to promote GI barrier integrity, healthy inflammatory and immune responses, and microbiome diversity.[10] The mechanism by which A. caccae promotes direct butyrate production is linked to its metabolic flexibility it is capable of both primary carbohydrate fermentation and secondary cross-feeding[15,18]. A. caccae can directly ferment various dietary carbohydrates, including glucose, fructose, sucrose, and prebiotic fibres, using the glycolytic and acetyl-CoA pathways, to deliver butyrate in the lower GI tract [15,19,20]. Additionally, A. caccae has been shown to ferment mucin-derived sugars such as glucose, mannose, galactose, and N-acetylgalactosamine, made by the mucin-degrading bacteria Akkermansia muciniphila (A. muciniphila), to produce butyrate, acetate, and lactate [21]. As an alternative butyrate synthesis method, A. caccae can also cross-feed on the lactate and acetate produced by other carbohydrate-fermenting gut bacteria, for example the l-lactate and acetate produced by Bifidobacterium species and the d-lactate and acetate produced by Lactobacillus species [13]. Interestingly, A. caccae can convert both d- and l-lactate into butyrate, potentially playing an important role in mitigating lactate buildup and supporting a balanced microbial ecosystem [13,22]. The cross-feeding conversion utilizes the acetyl-CoA pathway in which lactate is first oxidized to pyruvate and then converted to acetyl-CoA, which directly contributes to butyrate synthesis or interconverts with exogenous acetate to produce butyrate [23]. In a mouse model of prolonged sorbitol intolerance, out of several administered probiotics, only A. caccae significantly increased cecal butyrate levels [17]. A recent study isolated a strain of A. caccae from healthy infant microbiota and administered it together with lactulose, resulting in a significant increase in butyrate levels, which was not observed when lactulose was administered alone [19]. Another animal study administered A. caccae along with galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS). Even though GOS alone increased cecal lactate and butyrate compared to controls, co-administration of A. caccae and GOS significantly increased cecal and fecal butyrate concentrations even further and decreased lactate levels [24]. Conversely, in a controlled assembly of human GI microbiome, removing A. caccae from the community led to a marked decrease in butyrate production, emphasizing its direct contribution to butyrate synthesis [25].

Anaerostipes Helps Support GI Health

Through its direct butyrate production in the lower GI tract, A. caccae may help support GI health. Butyrate is a SCFA which plays a pivotal role in colon and mucosal health by nourishing colonocytes and supporting the intestinal epithelial barrier and healthy inflammatory responses [26-28]. Several studies suggest that butyrate may be especially supportive when delivered to the lower GI tract [10,27,29]. An in vitro study using human colonic epithelial cells showed that butyrate’s effects are mediated through its uptake via the monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT1), which is expressed on the luminal membrane of colonic cells [27]. Interestingly, the expression of MCT1 is upregulated by butyrate itself, suggesting that butyrate modulates its own transport to optimize its intracellular availability. This adaptive response promotes efficient butyrate absorption and cellular health in the colon [27]. In a murine model of peanut allergy and colitis, researchers used polymeric micelles to release butyrate in the lower GI tract, noting that traditional sodium butyrate administration is predominantly absorbed in the stomach and small intestine, which may limit its clinical relevance. The study found that mice treated with the butyrate micelles exhibited reduced anaphylactic response, improved gut barrier integrity, and an overall increase in butyrate-producing bacteria, particularly in Clostridium clusters IV and XIVa [10]. Butyrate has been shown to support the GI lining, gut barrier integrity, and healthy colonic epithelial cells (colonocytes) [30-32]. It nourishes colonocytes, serving as their primary energy source, thus supporting healthy colonic epithelium the thin layer of cells that lines the inner surface of the large intestine [26-28,30]. Colonocytes absorb butyrate and oxidize it in their mitochondria, producing CO₂ and ATP, which accounts for 70% to 80% of their energy supply, fuelling essential functions like electrolyte transport and intestinal barrier support [26,31,33]. Additionally, butyrate supports the intestinal epithelial barrier by supporting tight junctions and the mucus layer [31,32]. It promotes the expression, localization, and function of key tight junction proteins, such as tight junction protein 1 (TJP1), zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1), occludin, claudin-1, claudin-3, and claudin-4 [18,26,31,34]. Butyrate has been shown to maintain and control the actin-binding protein synaptopodin, which is expressed at high levels in tight junctions of the GI tract and is crucial for the integrity of the gut-barrier function [18,35]. Butyrate also promotes adenosine-monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) a key enzyme that acts as a cellular energy sensor. This activation further supports tight junction assembly and intestinal barrier function and mitigates permeability [31,34]. In porcine cells challenged with lipopolysaccharides (LPS), butyrate mitigated epithelial barrier disruption and significantly increased both mRNA and protein levels of claudin-3 and claudin-4, activating the Akt/mTOR signalling pathway and supporting tight junction assembly [36]. Transcriptomic analysis of colonic mucosa biopsies identified several genes associated with mucosal repair and regeneration that may be up-regulated by butyrate, such as the genes in the Wnt signalling pathway, cytoskeleton regulation, and bone morphogenetic protein antagonists [37]. Butyrate may also play an important role in promoting GI regularity by enhancing colonic motility and maintaining gut homeostasis [38,39]. An experimental animal study showed that germ-free mice (lacking microbiota and SCFAs) exhibited abnormal colonic motor patterns characterized by sluggish and disorganized contractions. When butyrate was administered, it restored normal motility, suggesting that butyrate directly supports healthy colonic function [38]. A randomized controlled trial (n = 24) found that individuals who responded positively to Bifidobacterium longum BB536 supplementation, measured by increased bowel movement frequency, had greater rises in fecal butyrate levels. These responders also had gut microbiota enriched with Clostridium clusters IV and XIVa (including A. caccae). This suggests that butyrate not only augments GI motility but does so as part of a microbial ecosystem that includes cross-feeding between Bifidobacterium and Clostridium species [39].

Anaerostipes Helps Support Healthy Gut Microbiome Diversity

The human GI tract has been estimated to contain approximately 38 × 1012 bacteria [40]. Commensal bacteria usually do not cause harm and contribute to host health, while opportunistic bacteria can cause health challenges under certain conditions [41,42]. Commensals play a role in the overall health of their host by participating in various metabolic pathways, modulating gene expression, and synthesizing beneficial bioactive compounds, such as SCFAs, amines, secondary bile acids, and vitamins [18]. By producing butyrate, A. caccae may support pH levels in the colon that are more suitable for commensal bacteria. SCFAs, like butyrate, are acidic compounds that can lower the pH of the colonic environment, which in turn favours butyrate-producing bacteria from the Bacillota phylum (like Roseburia and Anaerostipes) and undermines the viability of acid-sensitive species (like opportunistic bacteria from the Bacteroides genus) [28]. A. caccae supports gut microbiome balance through its butyrate production and nutrient cross-feeding, thus promoting competitive exclusion of pathogenic bacteria by commensal species. Co-culture studies with A. muciniphila show that A. caccae improves microbial community metabolic interactions, which may leave fewer resources available to opportunistic bacteria [43]. Interestingly, there seems to be a symbiotic cross-feeding at the intestinal mucus layer between A. caccae and A. muciniphila, a mucus-degrading gut bacterium, which breaks down host mucus into oligosaccharides and acetate. These A. muciniphila byproducts are then utilized by neighbouring, non-mucus-degrading bacteria, like A. caccae, to produce butyrate, which in turn supports a stable microbial ecosystem that benefits other keystone species, like A. muciniphila [21].A recent review article posits that butyrate supports a healthy microbiome by promoting a hypoxic environment, selective microbial diversity favouring commensal species including other anaerobic butyrogenic bacteria, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPAR-γ) signalling limiting opportunistic expansion, and the production of antimicrobial peptides [31]. Butyrate has been shown to stabilize hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) to maintain the anaerobic environment in the gut [18]. By oxidizing butyrate and consuming oxygen in the process, colonocytes can help create a hypoxic environment in the lumen, thus maintaining luminal anaerobiosis favourable to the commensal microbiota and stabilizing HIF [33,44]. In an animal model, inoculation with A. caccae restored normal Clostridia levels and protected mice from sorbitol-induced diarrhoea. There was a lasting impact through the butyrate produced by A. caccae, promoting a rise in other butyrate-producing Clostridia, such as members of the Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae families, supporting long-term microbial stability and GI health. The study also found that, mechanistically, butyrate promoted PPAR-γ signalling, reestablishing epithelial hypoxia in the colon a vital condition supporting a GI environment that favours the return of commensal, anaerobic bacteria like Clostridia species [17]. Anaerostipes May Show Promise in Food Allergies

Although this area is under active research, there is evidence to suggest that A. caccae plays an important role in immune health and the digestion of commonly challenging foods [18]. SCFAs, in particular butyrate, have been shown to improve food allergies, mitigate pathogen invasion, and promote barrier integrity by activating cell surface G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) and modulating histone deacetylases (HDACs) [45,46]. Through HDAC mitigation, butyrate may normalize the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and the antimicrobial activity of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated macrophages [32]. Butyrate acts as a signalling molecule in the gut, interacting with host receptors such as the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) and GPCRs, like GPR109a, GPR43, and GPR41. Activation of these receptors supports healthy immune responses by promoting interleukin (IL)-10-secreting T-reg cells and normalizing macrophage secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-22 [18,31,46]. Experimental studies have demonstrated that administration of A. caccae increases butyrate levels in the gut, which in turn supports lower allergen potential. For example, in a mouse model of cow’s milk and peanut allergy, administering a synbiotic of A. caccae and lactulose increased luminal butyrate levels and mitigated allergic responses. These effects were attributed to butyrate’s ability to support gut barrier integrity and promote healthy immune responses by suppressing epithelial alarmins, promoting follicular T-reg cells, lowering allergen-specific antibody levels, and reducing the risk of anaphylactic responses [19]. In another animal study, germ-free mice were colonized with fecal samples from healthy and cow’s milk-allergic infants to determine the impact of microbial communities on allergic responses. Mice colonized with healthy infant microbiota (including A. caccae) or monocolonized with A. caccae exhibited reduced markers of inflammation and allergy, including lower immunoglobulin E (IgE), IL-4, IL-13, and mouse mast cell protease 1 (mMCPT-1) levels [47]. Another controlled murine study evaluated the potential of butyrate-releasing polymeric micelles in mitigating peanut allergy and colitis. Intragastric administration of either neutral or negatively charged micelles allowed targeted butyrate delivery to the ileum or caecum, respectively. The butyrate-treated mice exhibited improved gut barrier function, increased butyrate-producing bacterial taxa in Clostridium cluster XIVa, reduced anaphylactic reactions to a peanut challenge, and lower levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and histopathologic damage in a T-cell-transfer model of colitis [10]. Further supporting evidence comes from a controlled study using non-obese diabetic mice. A third of the mice were colonized with a consortium of nine early-life commensal bacteria, including Anaerostipes (PedsCom), another third were germ-free (GF) mice, and the final third were colonized with a complex mature community (CMCom) modelling the adult gut microbiome. The results showed that only 26% of PedsCom mice developed diabetes, versus 60% of GF mice (p <0.5) and 63% of CMCom mice (p <0.01). These results were linked to the activation of peripheral T-reg cells, mucosal IgA, and IL-10-producing T-reg cells and the mitigation of pro-inflammatory interferon gamma-producing CD4-positive T cells in the pancreatic islets. Loss-of-function experiments confirmed that Anaerostipes was essential for the observed results [48]. Translation of these findings to human populations, as well as understanding all other confounding factors that may be at play, requires further investigation in the form of randomized controlled human trials. An in vitro (human neutrophil cultures) and ex vivo (murine colon organ cultures) experimental study investigated the effects of butyrate on inflammatory responses. The results suggest that butyrate may have mitigated nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) activation, pro-inflammatory cytokine release, and downregulated immune-related gene expression [49]. An animal model based on chickens suggests that A. caccae may support immune health through the gut-bone axis and its effect on the immune microenvironment of bone marrow [50]. Finally, an animal study of germ-free mice colonized with a mixture of 17 Clostridia strains found that, by producing butyrate and other SCFAs, these strains supported T-reg cell differentiation and function, healthy inflammatory responses, and reduced levels of ovalbumin (OVA)-specific IgE in an OVA-induced food allergy model [51].While clinical research in the form of randomized controlled human trials is needed to further elucidate these findings, current preclinical evidence positions A. caccae as a key microbial player in the direct production of butyrate in the lower GI tract, with important implications for GI and immune health, microbial community dynamics, and overall host well-being.

Conclusion

This case report describes the resolution of long-standing food intolerances following targeted restoration of anaerobic butyrateproducing capacity using Anaerostipes caccae CLB101™. The patient’s symptom improvement coincided with normalization of key anaerobic taxa and reduction of opportunistic organisms, suggesting a functional shift in microbial metabolism rather than isolated taxonomic change. While causality cannot be established from a single case, the findings support a biologically plausible role for butyrate-mediated barrier and ecosystem restoration in food intolerance. Further investigation in randomized controlled human studies is warranted. Double-blind placebo-controlled human clinical trials are recommended for future research. The probiotic seems safe, with no known side effects. The stool testing outcomes were significant, and one might postulate further on the test result outcomes: Commensals all improved and the argument could made for cross-feeding and other symbiotic signalling from Anaerostipes caccae CLB101™. If we assume that Anaerostipes caccae CLB101™increased mucin levels (one of the mechanisms of action for butyrate), then it would not be surprising to increase Akkermansia. Prevotella and Morganella might have decreased in abundance, since Anaerostipes caccae CLB101™ may directly compete with these taxa, in which case “crowding out” could make sense. It is also plausible that Anaerostipes caccae CLB101™ affected pH (or some other environmental variable) that impacted growth of these taxa. sIgA was measured in feces and showed a steep elevation, but an increase is not always negative. In fact, with some food allergy studies, research shows that treatment decreases IgE while increasing IgA. While sIgA plays a role responding to inflammation or infection, it is also important for homeostasis in the intestine, and many commensal organisms are coated with IgA in the feces.

Acknowledgements: Dr. David Reilly (CARE guidelines), and Jonathan Halcovage (editor) for support and guidance.

Funding: No funding or grants were provided for this case report.

References

- Gupta RS, Warren CM, Smith BM, Jiang J, Blumenstock JA, et al. (2019). Prevalence and Severity of Food Allergies Among US Adults. JAMA Network Open. 2: e185630.

- United States Census Bureau. (2022). Age and Sex Composition in the United States: 2022. United States Census Bureau. Retrived from online.

- Gupta RS, Warren CM, Smith BM, Blumenstock JA, Jiang J, et al. (2018). The Public Health Impact of Parent-Reported Childhood Food Allergies in the United States. Pediatrics. 142: e20181235.

- Campos M. (2020). Food Allergy, Intolerance, or Sensitivity: What’s the Difference, and Why Does It Matter. Harvard Health Online.

- Jackson KD, Howie LD, Akinbami LJ. (2013). Trends in Allergic Conditions Among Children: United States, 1997–2011. NCHS Data Brief. 121: 1-8.

- Zablotsky B, Black LI, Akinbami LJ. (2023). Diagnosed Allergic Conditions in Children Aged 0–17 Years: United States, 2021. NCHS Data Brief. 459: 1-8.

- Di Costanzo M, De Paulis N, Biasucci G. (2021). Butyrate: A Link Between Early Life Nutrition and Gut Microbiome in the Development of Food Allergy. Life. 11: 384.

- Hodgkinson K, El Abbar F, Dobranowski P, Manoogian J, Butcher J, et al. (2023). Butyrate’s Role in Human Health and the Current Progress Towards Its Clinical Application to Treat Gastrointestinal Disease. Clinical Nutrition. 42: 61-75.

- Shi J, Mao W, Song Y, Wang Y, Zhang L, et al. (2025). Butyrate Alleviates Food Allergy by Improving Intestinal Barrier Integrity Through Suppressing Oxidative Stress-Mediated Notch Signaling. iMeta. 4: e70024.

- Wang R, Cao S, Bashir MEH, Hesser LA, Su Y, et al. (2022). Treatment of Peanut Allergy and Colitis in Mice via the Intestinal Release of Butyrate From Polymeric Micelles. Nature Biomedical Engineering. 7: 38-55.

- Albenberg L, Esipova TV, Judge C, Bittinger K, Chen J, et al. (2014). Correlation Between Intraluminal Oxygen Gradient and Radial Partitioning of Intestinal Microbiota. Gastroenterology. 147: 10551063.

- Van Den Abbeele P, Belzer C, Goossens M, Kleerebezem M, De Vos EM, et al. (2013). Butyrate-Producing Clostridium Cluster XIVa Species Specifically Colonize Mucins in an In Vitro Gut Model. ISME Journal. 7: 949-961.

- Duncan SH, Louis P, Flint HJ. (2004). Lactate-Utilizing Bacteria, Isolated From Human Feces, That Produce Butyrate as a Major Fermentation Product. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 70: 5810-5817.

- Kadowaki R, Tanno H, Maeno S, Endo A. (2023). Spore-Forming Properties and Enhanced Oxygen Tolerance of Butyrate-Producing Anaerostipes spp. Anaerobe. 82: 102752.

- Schwiertz A, Hold GL, Duncan SH, Gruhl B, Collins MD, et al. (2002). Anaerostipes caccae gen. nov., sp. nov., a New Saccharolytic, Acetate-Utilising, Butyrate-Producing Bacterium From Human Faeces. Systematic and Applied Microbiology. 25: 46-51.

- Lopetuso LR, Scaldaferri F, Petito V, Gasbarrini A. (2013). Commensal Clostridia: Leading Players in the Maintenance of Gut Homeostasis. Gut Pathogens. 5: 23.

- Lee JY, Tiffany CR, Mahan SP, Kellom M, Rogers AWL, et al. (2024). High Fat Intake Sustains Sorbitol Intolerance After Antibiotic-Mediated Clostridia Depletion From the Gut Microbiota. Cell. 187: 1191-1205.

- Singh V, Lee G, Son H, Koh H, Kim ES, et al. (2023). Butyrate Producers, “The Sentinel of Gut”: Their Intestinal Significance With and Beyond Butyrate, and Prospective Use as Microbial Therapeutics. Frontiers in Microbiology. 13: 1103836.

- Hesser LA, Puente AA, Arnold J, Ionescu E, Mirmira A, et al. (2024). A Synbiotic of Anaerostipes caccae and Lactulose Prevents and Treats Food Allergy in Mice. Cell Host & Microbe. 32: 1163-1176.

- Falony G, Vlachou A, Verbrugghe K, Vuyst LD. (2006). Cross-Feeding Between Bifidobacterium longum BB536 and Acetate-Converting, Butyrate-Producing Colon Bacteria During Growth on Oligofructose. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 72: 7835-7841.

- Belzer C, Chia LW, Aalvink S, Chamlagain B, Piironen V, et al. (2017). Microbial Metabolic Networks at the Mucus Layer Lead to Diet-Independent Butyrate and Vitamin B12 Production by Intestinal Symbionts. mBio. 8: e00770-17.

- Kattel A, Morell I, Aro V, Lahtvee PJ, Vilu R, et al. (2023). Detailed Analysis of Metabolism Reveals Growth-Rate-Promoting Interactions Between Anaerostipes caccae and Bacteroides spp. Anaerobe. 79: 102680.

- Belenguer A, Duncan SH, Calder AG, Holtrop G, Louis P, et al. (2006). Two Routes of Metabolic Cross-Feeding Between Bifidobacterium adolescentis and Butyrate-Producing Anaerobes From the Human Gut. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 72: 3593-3599.

- Sato T, Matsumoto K, Okumura T, Yokoi W, Naito E, et al. (2008). Isolation of Lactate-Utilizing Butyrate-Producing Bacteria From Human Feces and In Vivo Administration of Anaerostipes caccae Strain L2 and Galacto-Oligosaccharides in a Rat Model: Synbiotic Use of Fecal Isolate and GOS. FEMS Microbiology Ecology. 66: 528-536.

- Clark RL, Connors BM, Stevenson DM, Hromada SE, Hamilton JJ, Amador-Noguez D, et al. (2021). Design of Synthetic Human Gut Microbiome Assembly and Butyrate Production. Nature Communications. 12: 3254.

- Karim MR, Iqbal S, Mohammad S, Morshed N, Haque A, et al. (2024). Butyrate’s (a Short-Chain Fatty Acid) Microbial Synthesis, Absorption, and Preventive Roles Against Colorectal and Lung Cancer. Archives of Microbiology. 206: 137.

- Cuff MA, Lambert DW, Shirazi-Beechey SP. (2002). Substrate-Induced Regulation of the Human Colonic Monocarboxylate Transporter, MCT1. Journal of Physiology. 539: 361-371.

- Holscher HD. (2017). Dietary Fiber and Prebiotics and the Gastrointestinal Microbiota. Gut Microbes. 8: 172-184.

- Vanhoutvin SALW, Troost FJ, Kilkens TOC, Lindsey PJ, Hamer HM, et al. (2009). The Effects of Butyrate Enemas on Visceral Perception in Healthy Volunteers. Neurogastroenterology and Motility. 21: 952.

- Treem WR, Ahsan N, Shoup M, Hyams JS. (1994). Fecal Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Children With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 18: 159-164.

- Hodgkinson K, El Abbar F, Dobranowski P, Manoogian J, Butcher J, et al. (2023). Butyrate’s Role in Human Health and the Current Progress Towards Its Clinical Application to Treat Gastrointestinal Disease. Clinical Nutrition. 42: 61-75.

- Kalkan AE, BinMowyna MN, Raposo A, Ahmad F, Ahmed F, et al. (2025). Beyond the Gut: Unveiling Butyrate’s Global Health Impact Through Gut Health and Dysbiosis-Related Conditions: A Narrative Review. Nutrients. 17: 1305.

- Gasaly N, Hermoso MA, Gotteland M. (2021). Butyrate and the FineTuning of Colonic Homeostasis: Implication for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 22: 3061.

- Peng L, Li ZR, Green RS, Holzman IR, Lin J. (2009). Butyrate Enhances the Intestinal Barrier by Facilitating Tight Junction Assembly via Activation of AMP-Activated Protein Kinase in Caco-2 Cell Monolayers. Journal of Nutrition. 139: 1619-1625.

- Wang RX, Lee JS, Campbell EL, Colgan SP. (2020). MicrobiotaDerived Butyrate Dynamically Regulates Intestinal Homeostasis Through Regulation of Actin-Associated Protein Synaptopodin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 117: 11648-11657.

- Yan H, Ajuwon KM. (2017). Butyrate Modifies Intestinal Barrier Function in IPEC-J2 Cells Through a Selective Upregulation of Tight Junction Proteins and Activation of the Akt Signaling Pathway. PLoS One. 12: e0179586.

- Luceri C, Femia AP, Fazi M, Di Martino C, Zolfanelli F, et al. (2016). Effect of Butyrate Enemas on Gene Expression Profiles and Endoscopic and Histopathological Scores of Diverted Colorectal Mucosa: A Randomized Trial. Digestive and Liver Disease. 48: 27-33.

- Vincent AD, Wang XY, Parsons SP, Khan WI, Huizinga JD. (2018). Abnormal Absorptive Colonic Motor Activity in Germ-Free Mice Is Rectified by Butyrate, an Effect Possibly Mediated by Mucosal Serotonin. American Journal of Physiology Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 315: G896-G907.

- Nakamura Y, Suzuki S, Murakami S, Nishimoto Y, Higashi K, et al. (2022). Integrated Gut Microbiome and Metabolome Analyses Identified Fecal Biomarkers for Bowel Movement Regulation by Bifidobacterium longum BB536 Supplementation: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal. 20: 5847-5858.

- Sender R, Fuchs S, Milo R. (2016). Revised Estimates for the Number of Human and Bacteria Cells in the Body. PLoS Biology. 14: e1002533.

- Krishnamurthy HK, Pereira M, Bosco J, George J, Jayaraman V, et al. (2023). Gut Commensals and Their Metabolites in Health and Disease. Frontiers in Microbiology. 14: 1244293.

- Packey CD, Sartor RB. (2009). Commensal Bacteria, Traditional and Opportunistic Pathogens, Dysbiosis and Bacterial Killing in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 22: 292-301.

- Chia LW, Hornung BVH, Aalvink S, Schaap PJ, De Vos WM, et al. (2018). Deciphering the Trophic Interaction Between Akkermansia muciniphila and the Butyrogenic Gut Commensal Anaerostipes caccae Using a Metatranscriptomic Approach. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 111: 859-873.

- Liu W, Fan X, Jian B, Wen D, Wang H, et al. (2023). The Signaling Pathway of Hypoxia Inducible Factor in Regulating Gut Homeostasis. Frontiers in Microbiology. 14: 1289102.

- Yoo J, Groer M, Dutra S, Sarkar A, McSkimming D. (2020). Gut Microbiota and Immune System Interactions. Microorganisms. 8: 1587.

- Parada Venegas D, De La Fuente MK, Landskron G, González MJ, Quera R, et al. (2019). Short-Chain Fatty Acids-Mediated Gut Epithelial and Immune Regulation and Its Relevance for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Frontiers in Immunology. 10: 277.

- Feehley T, Plunkett CH, Bao R, Hong SMC, Culleen E, et al. (2019). Healthy Infants Harbor Intestinal Bacteria That Protect Against Food Allergy. Nature Medicine. 25: 448-453.

- Green J, Deschaine J, Lubin JB, Flores JN, Maddux S, et al. (2024). Early-Life Exposures to Specific Commensal Microbes Prevent Type 1 Diabetes. bioRxiv. 1: 1-10.

- Tedelind S, Westberg F, Kjerrulf M, Vidal A. (2007). Anti-Inflammatory Properties of the Short-Chain Fatty Acids Acetate and Propionate: A Study With Relevance to Inflammatory Bowel Disease. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 13: 2826.

- Lyu Z, Yuan G, Zhang Y, Zhang F, Liu Y, et al. (2024). Anaerostipes caccae CML199 Enhances Bone Development and Counteracts Aging-Induced Bone Loss Through the Butyrate-Driven Gut-Bone Axis: The Chicken Model. Microbiome. 12: 215.

- Atarashi K, Tanoue T, Oshima K, Suda W, Nagano Y, et al. (2013). Treg Induction by a Rationally Selected Mixture of Clostridia Strains From the Human Microbiota. Nature. 500: 232-236.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.