An Infected Urachal Cyst: Ultrasound and Computed Tomography Findings

by Lorenzo Pinto1, Emilio Vicenzo2, Luigi Pirolo2, Francesca Rosa Setola2, Adriana Paludi1, Gaia Peluso3, Domenico Barbato3, Fabio Sandomenico2*

1Radiology Unit, S. Maria delle Grazie Hospital, Pozzuoli (Naples), Italy

2Radiology Unit, Buon Consiglio Fatebenefratelli Hospital, Naples, Italy

3Surgery Unit, Buon Consiglio Fatebenefratelli Hospital, Naples, Italy

*Corresponding author: Fabio Sandomenico, Chief Director of Radiology Unit, Buon Consiglio Fatebenefratelli, Via Manzoni 220, 80123, Naples, Italy

Received Date: 16 December 2025

Accepted Date: 22 December 2025

Published Date: 24 December 2025

Citation: Pinto L, Vicenzo E, Pirolo L, Setola FR, Paludi A, et al. (2025) An Infected Urachal Cyst: Ultrasound and Computed Tomography Findings. J Surg 10:11524 https://doi.org/10.29011/2575-9760.011524

Abstract

The urachus originates from the upper part of the urogenital sinus and forms a connection between the dome of the bladder and the allantoic duct during fetal development. Positioned behind the abdominal wall and in front of the peritoneum within the space of Retzius, the urachus undergoes obliteration before birth and transforms into a vestigial structure called the medial umbilical ligament [1]. However, in some cases, incomplete obliteration leads to the persistence of the urachus as a patent urachus, urachal cyst, urachal sinus, or urachal diverticulum [2]. A urachal cyst develops when the urachal lumen’s umbilical and vesical ends close while an intervening section remains open and filled with fluid [3]. Typically, urachal cysts go unnoticed until they become complicated by infection or bleeding. When examined through radiology, an uncomplicated urachal cyst manifests as a collection of simple fluid located in the midline of the anterior abdominal wall, between the umbilicus and the pubis, often contiguous with the bladder dome. For diagnostic evaluation, Ultrasound (US) is usually the starting point, enabling the localization and delineation of the mass’s boundaries. We describe Ultrasound and CT findings in a young patient with an infected urachal cyst that arrived at our observation.

Keywords: Complications; Computed Tomography; Ultrasound; Urachal Cyst; Urachal Remnant

Case Report

Investigation

Clinical Presentation

A 16-year-old female with no significant medical history arrived at our Emergency Department complaining of pelvic pain that had been progressively worsening over the past two days. On examination, her blood pressure was 110/70 mmHg, and she had a temperature of 38°C. Abdominal palpation elicited mild tenderness in the left iliac fossa. Laboratory tests revealed an elevated white blood cell count (13.52 x 10^3/uL) and an increased percentage of neutrophils (79%), along with a significantly elevated C-reactive protein level (68.8 mg/L), indicating an ongoing inflammatory process.

Investigation

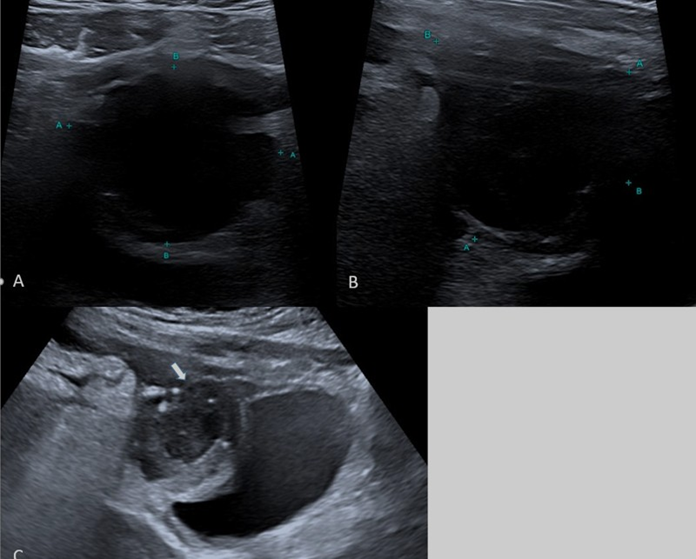

Ultrasonography (US) was performed to assess the pelvic region. The US findings indicated a heterogeneous collection of approximately 5 cm in diameter, which appeared to be connected with a subfascial-mesohypogastric urachal remnant. Additionally, marked hyperechogenicity was observed in the locoregional omental tissue (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Ultrasound - A,B) US with small parts (7,4-13 Mhz) probe shows supravesical cystic mass with irregularity of contours C) US with convex (3-8 MHz) probe shows the sopravescical cystic mass (white arrow) in communication with patent urachus (head white arrows) confirmed as a urachal cyst following image-guided aspiration.

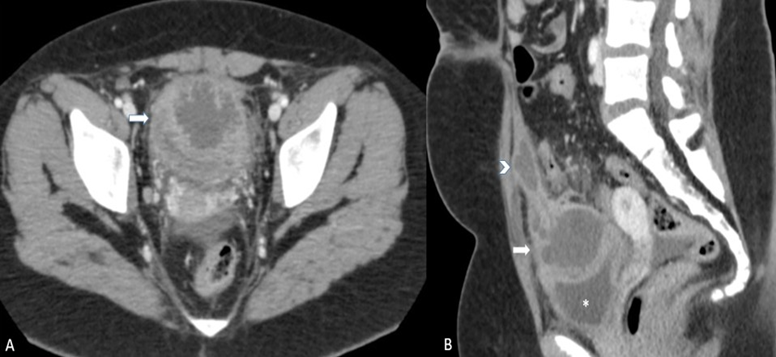

To further investigate the pelvic findings, a Contrast Enhenaced Computed Tomography (CECT) scan was performed two days later. The CT scan revealed an oval, hypoattenuating formation with irregularly thickened walls, with contrast enhancement after contrast medium injection suggestive of an abscess (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Contrast Enhanced CT: A) Axial scan: supravesical cystic structure with irregular thickening and contrast enhancing of the walls. B) Sagittal MPR reconstruction well depict communication of the cystic mass (white arrow) with another hypoattenuating structure, extending beneath the abdominal wall to the subumbilical region and corresponding to a fluid-containing urachal remnant (head arrow). The bladder was impressed from the cystic mass (asterisc).

This formation was comunicating with another hypoattenuating structure, extending beneath the abdominal wall to the subumbilical region for approximately 55 mm ad corresponding to a fluidcontaining urachal remnant. It also exerted an impression on the upper wall of the bladder, without a well-defined cleavage plane, and demonstrated wall thickening. The CT scan also indicated no clear cleavage plane with the right wall of the sigma colon (in the context of dolichosigma), which exhibited wall thickening. Additionally, the pelvic cavity appeared imbibed and engorged, with several centimeter-sized lymph nodes identified. A small amount of free fluid was present in the pelvic cavity and the right iliac fossa.

Treatment and Management

Given the severity of the infected urachal cyst, the patient underwent aspiration and drainage with ultrasound guidance. Intravenous antibiotics were initiated to manage the infection and alleviate symptoms. Surgical intervention was initially considered but deferred based on the patient’s response to medical treatment. On follow-up imaging conducted on August 1st, a reduction in the volume of the abscess collection was noted. The infected urachal cyst measured approximately 30x24x26 mm compared to the previous CT scan measurements of 57x57x42 mm. A pig-tail catheter remained in place for continuous drainage. While the fluid content above the urachal remnant persisted, it appeared less dense.

Differential Diagnosis

When considering the differential diagnosis of urachal cysts, it is essential to differentiate between infected and non-infected cysts, as well as other potential pelvic pathologies. Infection of a persistent urachus is a common benign complication, often caused by Staphylococcus aureus, and may present with various clinical signs and symptoms [4]. Infected urachal cysts can pose a diagnostic challenge, particularly on initial sonographic evaluation when clinical symptoms are absent. Greyscale ultrasound typically reveals a midline extraperitoneal structure extending from the bladder dome to the umbilicus, often containing internal echoes. In cases where a urachal cyst becomes infected, it may exhibit the following characteristics at US: (a) mixed echogenicity, (b) attenuation and signal intensity deviating upward from those of water at CT and MR imaging, respectively, and (c) thickening of the urachal wall [5,6]. This appearance may mimic other pelvic pathologies, such as hematomas. Computed Tomography (CT) imaging can show infected urachal cysts as thick-walled and irregular structures with peripheral enhancement and underlying bladder wall thickening [7,8].

Ultrasound may reveal a complex cystic mass in the midline above the urinary bladder. Contrast-enhanced CT can demonstrate a heterogeneous collection with a thick enhancing irregular wall and central non-enhancing low attenuation. Malignant transformation of a urachal remnant is rare but can present unique challenges in differential diagnosis. Clinical presentation varies, with hematuria being the most common symptom, occurring in up to 80% of cases. Mucinuria, a rare symptom, can also occur in urachal cancers, raising suspicion and warranting further investigation Urachal malignancies can exhibit various appearances on imaging studies. On ultrasound, they may appear as hyperechogenic soft-tissue lesions with internal vascularity on color Doppler imaging. On CT, urachal malignancies can present as solid-cystic masses extending toward the umbilicus with irregular, enhancing walls. Up to 90% of cases originate from the juxtavesical urachus, extending cranially into the space of Retzius. Alternatively, they may manifest as predominantly cystic masses or as midline or paramidline enhancing nodules arising from the anterosuperior aspect of the urinary bladder [9].

Conclusion and Discussion

This clinical case highlights the significance of diagnosing an infected urachal cyst in young patients. Timely recognition and intervention can lead to a favorable outcome, as demonstrated in this 16-year-old female. Urachal abnormalities, although rare, should be considered in the differential diagnosis of pelvic pain and inflammation in adolescents [4]. Early diagnosis is essential in preventing complications such as abscess formation and the need for more extensive surgical interventions. A multidisciplinary approach, involving pediatricians, radiologists, and surgeons, ensures comprehensive care and better patient outcomes. Regular follow-up and monitoring are essential for assessing treatment efficacy and ensuring the patient’s complete recovery.

Learning Points

Urachal abnormalities, although rare, should be considered in adolescents presenting with pelvic pain and inflammation. Timely recognition and intervention can prevent complications such as abscess formation, reducing the need for extensive surgical interventions. A multidisciplinary approach involving pediatricians, radiologists, and surgeons ensures comprehensive care and improved patient outcomes. This case report exemplifies the importance of prompt diagnosis and management in cases of infected urachal cysts, ultimately leading to a favorable outcome.

Funding: None declared.

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient(s) for publication of this case report, including accompanying images.

References

- Berrocal T, López-Pereira P, Arjonilla A, Gutiérrez J (2022) Anomalies of the Distal Ureter, Bladder, and Urethra in Children: Embryologic, Radiologic, and Pathologic Features 22: 1139-1164.

- Suita S, Nagasaki A (1996) Urachal remnants. Semin Pediatr Surg 5: 107-115.

- Khati NJ, Enquist EG, Javitt MC (1998) Imaging of the umbilicus and periumbilical region. RadioGraphics 18: 413-431.

- Goldman IL, Caldamone AA, Gauderer M, Hampel N, Wessehoeft CW, et al. (1988) Infected urachal cysts: a review of ten cases. J Urol 140: 375-378.

- Yu JS, Kim KW, Lee HJ, Lee YJ, Yoon CS, et al. (2001) Urachal remnant diseases: spectrum of CT and US findings. RadioGraphics 21: 451-461.

- Cilento BG Jr, Bauer SB, Retik AB, Peters CA, Atala A (1998) Urachal anomalies: defining the best diagnostic modality. Urology 52: 120-122.

- Das JP, Vargas HA (2020) The urachus revisited: multimodal imaging of benign & malignant urachal pathology British Journal of Radiology 93: 20190118.

- Parada Villavicencio C, Adam SZ, Nikolaidis P, Yaghmai V, Miller FH (2016) Imaging of the urachus: anomalies, complications, and mimics. Radiographics 36: 2049-2063.

- Ashley RA, Inman BA, Sebo TJ, Leibovich BC, Blute ML, et al. (2006) Urachal carcinoma: clinicopathologic features and long-term outcomes of an aggressive malignancy. Cancer 107: 712-720.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.