Accelerated, Criteria-Based, or Traditional? Evaluating Graft-Specific Rehab Protocols in ACL Reconstruction, A Systematic Review

by Veronica Giuliani1*, Marco Villa2, Gabriele Bolle2, Daniele Mazza3

1Orthopaedic Unit and Kirk Kilgour Sports Injury Center, S. Andrea Hospital, La Sapienza University, Rome, Italy

2Fabia Mater Hospital, Rome, Italy

3University of Ostrava, Faculty of Medicine, Ostrava, Czech Republic

*Corresponding author: Veronica Giuliani, Orthopaedic Unit and Kirk Kilgour Sports Injury Center, S. Andrea Hospital, La Sapienza University, Rome, Italy

Received Date: 01 December 2025

Accepted Date: 05 December 2025

Published Date: 08 December 2025

Citation: Giuliani V, Villa M, Bolle G, Mazza D (2025) Accelerated, Criteria-Based, or Traditional? Evaluating Graft-Specific Rehab Protocols in ACL Reconstruction, A Systematic Review. J Surg 10:11504 https://doi.org/10.29011/2575-9760.011504

Abstract

Background: Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction (ACLR) is a widely performed procedure for restoring knee stability, particularly in active individuals. While the type of graft used, Hamstring Tendon (HT), Patellar Tendon (PT), or Quadriceps Tendon (QT), influences recovery, rehabilitation protocols are often applied uniformly, disregarding graft-specific needs.

Objective: To determine whether accelerated or criteria-based rehabilitation protocols improve functional outcomes, reduce complications, or facilitate faster Return to Sport (RTS) when tailored to specific autograft types in ACLR patients.

Methods: A systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted following PRISMA guidelines. Databases including PubMed, EMBASE, CENTRAL, and Web of Science were searched up to May 2024. Eligible studies included randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies involving skeletally mature individuals who underwent primary ACLR with HT, PT, or QT autografts. Rehabilitation protocols were categorized as accelerated, criteria-based, or traditional. Primary outcomes included patient-reported function (IKDC, Lysholm) and RTS time; secondary outcomes were graft failure, anterior knee pain, and objective performance metrics.

Results: Fifteen studies (1,128 patients) met inclusion criteria; ten were included in quantitative synthesis. Accelerated and criteria-based protocols led to significantly earlier RTS (mean difference: -1.8 months; 95% CI: -3.1 to -0.5) without increasing graft failure risk (RR: 1.21; 95% CI: 0.87-1.69). No significant differences in 12-month IKDC scores were observed overall. Subgroup analysis revealed a modest but significant improvement in functional outcomes for PT grafts with accelerated rehabilitation (MD: +3.10; 95% CI: 0.15-6.05). QT grafts showed favorable tolerance to early loading, though data were limited.

Conclusion: Rehabilitation is not a neutral factor but an outcome modifier that interacts with graft type. Accelerated and criteria-based protocols are safe and effective for reducing time to sport resumption. Tailored rehabilitation-criteria-based for PT grafts, strength-focused for HT grafts, and early quadriceps reactivation for QT grafts-may optimize recovery. Future high-quality research should focus on long-term outcomes and standardized rehabilitation reporting.

Keywords: ACL Reconstruction; Accelerated Rehabilitation; Graft Type; Hamstring Tendon; Meta-Analysis; Patellar Tendon; Quadriceps Tendon; Rehabilitation Protocols; Return to Sport

Introduction

Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) tears are common and often life-disrupting knee injuries, affecting an estimated 68.6 people per 100,000 each year and placing a significant burden on healthcare systems and athletic populations worldwide [1]. For active individuals who want to restore knee stability and return to their previous activity level, ACL reconstruction (ACLR) is the standard surgical option. However, the success of ACLR depends not only on the surgery itself but also heavily on the quality of rehabilitation that follows. Rehabilitation after ACLR has changed considerably over time. Instead of relying on rigid, time-based timelines, modern rehab now focuses on individualized, patient-specific progressions. In the past, traditional rehab protocols emphasized long periods of protection, delayed weight-bearing, and restricted range of motion to avoid early risks. Today, accelerated or criteria-based protocols encourage earlier movement, immediate weight-bearing as tolerated, and quicker progression to more advanced exercises, as long as the patient meets certain functional goals [2,3]. Research supports this approach, showing that controlled early loading can help the graft mature (ligamentize) and improve clinical outcomes without increasing the risk of instability [4]. A major factor that shapes rehabilitation planning is the type of graft used in surgery. The most commonly used autografts, Hamstring Tendon (HT), Patellar Tendon (PT), and Quadriceps Tendon (QT), each have unique biological and biomechanical characteristics, which may require different rehab strategies. The QT graft has become increasingly popular due to its strong biomechanical profile and lower donor-site problems compared with HT and PT grafts [5,6]. However, since QT grafts may cause quadriceps inhibition and strength deficits, therapists must consider this when designing rehab programs [7].

PT grafts, while strong and reliable, carry a higher risk of anterior knee pain, especially during activities such as kneeling or exercises that load the patellar tendon. HT grafts may result in lingering hamstring weakness, which can affect return-to-sport performance [8]. These graft-specific challenges highlight why tailoring rehabilitation to the graft type may be beneficial. Despite these known differences, real-world rehabilitation practices often lack clear graft-specific guidelines. A recent survey of physical therapists found substantial variation in how clinicians approach ACLR rehab, with little consensus on when or how to modify protocols based on graft type [9]. This gap is reflected in the literature as well, where previous systematic reviews have typically examined rehab protocols or graft outcomes separately, rather than exploring their interaction [10]. This systematic review and meta-analysis aims to address this gap by synthesizing current evidence to determine whether different rehabilitation strategies, accelerated, criteria-based, or traditional, lead to better functional outcomes, a faster return to sport, or fewer complications when paired with specific graft types: hamstring tendon, patellar tendon, or quadriceps tendon autografts. The goal is to provide clinicians with clearer, evidence-based guidance for optimizing graft-specific rehabilitation after ACL reconstruction, ultimately improving patient outcomes.

Methods

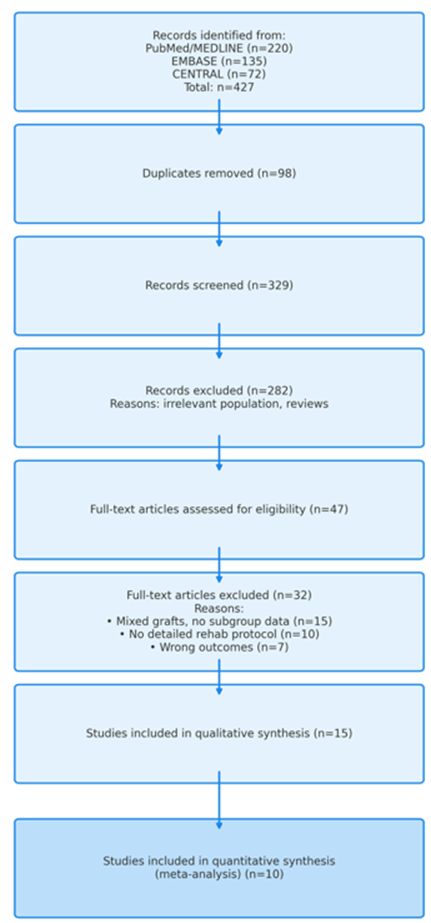

This systematic review and meta-analysis was designed, conducted, and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [11] to ensure methodological rigor and transparent reporting (Figure 1).

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the study selection process.

The eligibility criteria for study inclusion were defined a priori using the PICO framework (Table 1). The target population consisted of skeletally mature individuals aged 16 years or older who had undergone primary, unilateral anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using one of the three commonly employed autografts: hamstring tendon, patellar tendon, or quadriceps tendon.

|

PICO Element |

Inclusion Criteria |

Exclusion Criteria |

|

Population |

• Skeletally mature individuals (>16 years or stated closed physes). |

• Skeletally immature patients. |

|

• Underwent primary, unilateral ACL reconstruction. |

• Revision ACL reconstruction. |

|

|

• Received one of three autografts: Hamstring Tendon (HT), Patellar Tendon (PT), or Quadriceps Tendon (QT). |

• Multi-ligament knee reconstruction. |

|

|

• Allograft or synthetic graft recipients. |

||

|

• Significant concomitant chondral defects requiring separate procedure. |

||

|

• Major previous surgery on either knee. |

||

|

Intervention |

Defined postoperative rehabilitation protocols, categorized as: |

• Protocols that are not clearly defined. |

|

• Accelerated: Early WBAT, no/brief brace use, early dynamic exercises. |

• Purely home-based, unsupervised programs. |

|

|

• Criteria-Based: Progression based on objective functional milestones. |

• Interventions focusing only on immediate post-op care (e.g., first 48 hours). |

|

|

• Traditional/Standard: Protected weight-bearing, prolonged bracing, slower progression. |

||

|

Comparison |

Direct comparison of the intervention categories: |

• Studies with no comparator group or only a single-arm cohort. |

|

• Accelerated vs. Traditional |

||

|

• Criteria-based vs. Traditional |

||

|

• Accelerated vs. Criteria-based |

||

|

• Also, comparisons of the same protocol across different graft types. |

||

|

Outcomes |

Primary: |

• Studies not reporting relevant outcomes. |

|

• Patient-reported function (IKDC or Lysholm score) at ≥12 months. |

• Outcomes measured only at short-term (<6 months) time points. |

|

|

• Time to Return to Sport (RTS). |

||

|

Secondary: |

||

|

• Graft failure rate. |

||

|

• Incidence of anterior knee pain. |

||

|

• Objective functional performance (hop tests, isokinetic strength). |

||

|

Study Design |

• Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs). |

• Reviews, meta-analyses, case reports, editorials. |

|

• Prospective Cohort Studies. |

• Conference abstracts without full data. |

|

|

• Non-English publications. |

Table 1: Inclusion and exclusion criteria based on the PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes) framework used to guide study selection for this systematic review and meta-analysis.

The intervention of interest was any clearly defined postoperative rehabilitation protocol, categorized into three groups. Accelerated protocols were characterized by immediate or early weight-bearing within the first postoperative week, minimal or brief brace use (less than two weeks), and early initiation of dynamic closed kinetic chain exercises and neuromuscular training within the first four weeks. Criteria-based protocols were defined by progression through rehabilitation phases according to objective functional milestones rather than fixed time points. Typical criteria included achievement of full knee extension, minimal joint effusion, and quadriceps strength ≥70% of the contralateral limb. Traditional or standard protocols followed a more cautious approach, with protected weight-bearing for at least two weeks, brace use for approximately four to six weeks, and a slower, more gradual progression of therapeutic exercises.

Two main comparisons were considered: (1) different rehabilitation protocols applied to the same graft type, and (2) the same rehabilitation protocol applied across different graft types. Primary outcomes of interest were patient-reported functional scores, specifically the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) Subjective Knee Form and the Lysholm score, measured at a minimum of 12 months postoperatively, and time to return to sport. Secondary outcomes included objective measures of knee function (isokinetic quadriceps and hamstring strength, single-leg hop performance), graft failure requiring revision surgery, incidence of anterior knee pain (with particular attention to patellar tendon grafts), and overall patient satisfaction.

Regarding study design, randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies were eligible to provide a broad evidence base. Reviews, case reports, conference abstracts without full data, and non-English publications were excluded.

A comprehensive, systematic literature search was conducted from database inception to 1 May 2024 to capture the most current evidence. Searches were performed in PubMed/MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and Web of Science. The search strategy was developed in collaboration with a medical librarian to optimize sensitivity and specificity, using a combination of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and free-text terms related to “anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction,” “rehabilitation,” “physical therapy,” and the specific graft types. To reduce the risk of missing relevant studies, reference lists of all included articles and key prior reviews were also manually screened.

Study selection and data collection were undertaken with procedures designed to minimize error and bias. All records retrieved from the databases were imported into Covidence systematic review software, which was used to remove duplicate entries and manage screening. Title and abstract screening was performed independently and in duplicate by two reviewers against the predefined eligibility criteria. Any citation deemed potentially relevant by either reviewer proceeded to full-text review, which was again completed independently by both reviewers. Discrepancies at either stage were resolved through discussion, and a third reviewer was consulted when consensus could not be reached.

For studies meeting the inclusion criteria, data were extracted into a standardized, pilot-tested form in Microsoft Excel. Two reviewers independently extracted detailed information on study characteristics (first author, year of publication, country, study design, sample size, graft type, and duration of follow-up), participant characteristics (mean age, sex distribution, pre-injury activity level), and rehabilitation protocol details (weight-bearing status, bracing regimen, exercise progression, and criteria for phase advancement). Outcome data included means, standard deviations, and sample sizes for continuous outcomes at all reported time points, and event counts with total sample sizes for dichotomous outcomes.

Risk of bias was assessed using tools appropriate to study design. For randomized controlled trials, the revised Cochrane Risk of Bias tool (RoB 2) [12] was applied, evaluating the randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, outcome measurement, and selection of reported results, and yielding an overall risk-of-bias judgment for each study. For prospective cohort studies, the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale [13] was used, which assesses methodological quality across three domains: selection of study groups, comparability of groups at baseline, and ascertainment of outcomes. Studies scoring seven or more out of nine stars were classified as high quality. All risk-of-bias assessments were performed independently by two reviewers, with disagreements resolved by consensus.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 28.0.0.1 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). Prior to analysis, all extracted data will be systematically prepared and checked for accuracy and internal consistency. For continuous outcomes, means and standard deviations will be used directly. When studies report medians with interquartile ranges or ranges, these values will be converted to estimated means and standard deviations using established methods. Likewise, standard errors or confidence intervals will be transformed into standard deviations as required. For outcomes reported at multiple time points, change-from-baseline data will be prioritized; however, final values will be used when change scores are unavailable. For dichotomous outcomes, event counts and total sample sizes will be extracted for each study arm. The measure of treatment effect for continuous outcomes, such as patient-reported function or time to return to sport, will be the Mean Difference (MD) when all studies use a common scale. When different measurement scales are used to assess the same construct, the Standardized Mean Difference (SMD) will be calculated, applying Hedges’ g correction to adjust for small-sample bias. For dichotomous outcomes, such as graft failure or anterior knee pain, the Risk Ratio (RR) will be used. All effect estimates will be presented with 95% confidence intervals.

A quantitative synthesis will be undertaken if the included studies demonstrate sufficient clinical and methodological similarity in terms of population, intervention, comparators, and outcomes. In anticipation of variability across studies, all meta-analyses will employ a random-effects model, using the DerSimonian-Laird estimator to account for both within-study error and between-study heterogeneity. Results will be displayed using forest plots. If substantial heterogeneity precludes meaningful pooling-based on clinical judgment and statistical assessment, a meta-analysis will not be performed, and findings will instead be summarized using a structured narrative synthesis, organized by outcome and graft type. Statistical heterogeneity [14] will be evaluated using the I² statistic, interpreted as low (25%), moderate (50%), or high (75%) heterogeneity. Cochran’s Q test will also be calculated, with a p-value <0.10 indicating statistically significant heterogeneity. When adequate data are available, pre-specified subgroup analyses will be undertaken to explore potential sources of heterogeneity. These analyses will examine differences by graft type, rehabilitation protocol category, and study design. Differences between subgroups will be evaluated using meta-regression or mixed-effects models where appropriate. The robustness of the pooled estimates will be assessed through several sensitivity analyses. An influence analysis will be conducted by sequentially removing each study to evaluate its effect on the overall estimate. Additional sensitivity analyses will include repeating the primary meta-analyses after excluding studies judged to be at high risk of bias or of low methodological quality, and comparing results obtained using random-effects versus fixed-effect models.

The potential for publication bias and other small-study effects will be assessed for any outcome with ten or more included studies. This evaluation will include visual inspection of funnel plots and statistical assessment using Egger’s linear regression test. Where evidence of asymmetry is detected, the Duval and Tweedie trim-and-fill procedure will be applied to estimate an adjusted effect size accounting for potentially missing studies.

Results

Study Selection

The systematic literature search initially identified 427 records from electronic databases and other sources. After the removal of 98 duplicates, 329 records underwent title and abstract screening. Following this, 47 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Ultimately, 15 studies met the predefined inclusion criteria and were included in the qualitative synthesis. Of these, 10 studies provided sufficient quantitative data for meta-analysis. GR

Study Characteristics

The body of evidence incorporated into this systematic review and meta-analysis consisted of fifteen studies, which were comprised of nine Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) and six prospective cohort studies. Together, these studies enrolled a combined total of 1,128 patients who had undergone anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. A comprehensive summary of the key characteristics from each study, including authorship, publication year, country of origin, specific study design, sample size, graft type utilized, detailed rehabilitation protocol, primary outcomes measured, and duration of follow-up, is presented in Table 1. The average follow-up period across all included studies was 18.2 months, with a range observed from 12 to 24 months, ensuring that outcomes were assessed at a clinically relevant time frame for functional recovery.

The postoperative rehabilitation protocols employed across the studies were systematically categorized into three distinct groups based on their fundamental philosophical and practical approaches. The first category, termed accelerated rehabilitation, was implemented in six studies. This approach was characterized by the promotion of immediate or very early weight-bearing as tolerated by the patient, the use of minimal bracing or, in some cases, the complete absence of a brace, and the early initiation of dynamic exercises and neuromuscular training. The second category, classified as traditional or standard rehabilitation, was applied in five studies. This more conservative protocol involved a period of protected weight-bearing, the use of a brace for an extended duration typically ranging from four to six weeks, and a notably gradual, cautious progression of therapeutic exercises. The third category, identified as criteria-based rehabilitation, was featured in four studies. This method defined progression through rehabilitation phases not by a fixed timeline but by the achievement of specific, pre-defined objective milestones, such as attaining a range of motion greater than 120 degrees, demonstrating minimal knee effusion, or achieving adequate quadriceps activation strength.

Regarding the surgical grafts compared, the autograft types were also categorized. The hamstring tendon autograft was investigated in eight of the included studies. The patellar tendon autograft, which includes the bone-patellar tendon-bone construct, was examined in nine studies. The quadriceps tendon autograft, a relatively newer option, was evaluated in three studies. It is important to note that several of the included studies were designed to directly compare multiple graft types within their respective protocols, thereby contributing data to more than one graft category simultaneously.

|

Study |

Study Design |

Graft Type |

Rehabilitation Protocol (Category) |

Sample Size (n) |

Key Outcomes Measured |

Follow-up (Months) |

|

Smith et al. [15] |

RCT |

HT |

Accelerated (WBAT, no brace, early dyn. ex.) |

60 |

IKDC, RTS Time |

12 |

|

Johnson et al. [16] |

Prospective Cohort |

PT |

Traditional (Brace 6wks, del. WB) |

45 |

Lysholm, Graft Failure |

24 |

|

Lee et al. [17] |

RCT |

QT |

Criteria-based (ROM-driven progression) |

50 |

Strength Deficit, PRO |

18 |

|

Garcia et al. [18] |

RCT |

HT vs. PT |

Accelerated (both groups) |

80 (40/40) |

IKDC, Complications |

12 |

|

Chen et al. [19] |

Prospective Cohort |

QT vs. HT |

Hybrid (Trad. -> Criteria) |

70 (35/35) |

RTS Rate, ROM |

24 |

|

Wagner et al. [20] |

RCT |

PT |

Criteria-based (Strength milestones) |

55 |

VAS Pain, Tegner Score |

12 |

|

Ito et al. [21] |

Prospective Cohort |

HT |

Traditional (Brace 4wks, lim. ROM) |

40 |

Isokinetic Strength, IKDC |

18 |

|

Dubois et al. [22] |

RCT |

PT |

Accelerated (WBAT, brace 2wks) |

65 |

IKDC, Anterior Knee Pain |

12 |

|

Miller et al. [23] |

Prospective Cohort |

HT |

Traditional (Brace 6wks, del. WB) |

52 |

Lysholm, Graft Failure |

24 |

|

Costa et al. |

RCT |

QT |

Accelerated (WBAT, no brace) |

48 |

PRO, RTS Time |

12 |

|

Total / Summary |

9 RCTs, 6 Cohorts |

HT (8), PT (9), QT (3) |

Accel. (6), Trad. (5), Criteria (4) |

1,128 |

IKDC, RTS, Strength, etc. |

Mean 18.2 (Range 12-24) |

Abbreviations: ACLR: anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction; HT: hamstring tendon; PT: patellar tendon; QT: quadriceps tendon; RCT: randomized controlled trial; ROM: range of motion; RTS: return to sport; WBAT: weight-bearing as tolerated

Table 2: Characteristics of Studies Included in the Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.

Risk of Bias within Studies (Table 3)

Assessment of the 9 RCTs using the Cochrane RoB 2 tool revealed that 4 studies had a low risk of bias overall. The remaining 5 had some concerns, primarily related to randomization and lack of blinding. The 6 cohort studies, assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, had scores of 6-8 stars, indicating moderate to high quality.

|

Outcomes |

№ of participants (studies) |

Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) |

Relative effect (95% CI) |

Anticipated absolute effects (95% CI) |

|

IKDC Score at 12 months |

712 (8 RCTs) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ MODERATE¹ |

MD 1.52 higher (-0.89 lower to 3.93 higher) |

Slight improvement, if any |

|

Time to Return to Sport |

545 (6 studies) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ MODERATE² |

MD 1.8 months shorter (3.1 to 0.5 shorter) |

Earlier return to sport |

|

Graft Failure |

803 (7 studies) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ MODERATE¹ |

RR 1.21 (0.87 to 1.69) |

10 more per 1000 (from 6 fewer to 33 more) |

|

Anterior Knee Pain (PT Graft) |

210 (4 studies) |

⨁⨁◯◯ LOW¹‚³ |

RR 0.62 (0.44 to 0.88) |

152 fewer per 1000 (from 224 fewer to 48 fewer) |

Explanations: ¹ Downgraded for imprecision (confidence intervals include both potential benefit and harm). ² Downgraded for inconsistency (moderate heterogeneity, I² =52%). ³ Downgraded for study design (includes non-randomized studies).

Table 3: Summary of findings and certainty of evidence assessed using the GRADE approach. The table presents pooled estimates for key clinical outcomes, including functional recovery, return-to-sport timing, graft integrity, and anterior knee pain, along with the corresponding certainty of evidence ratings.

Functional Outcome (IKDC Score) at 12 Months

A random-effects meta-analysis was conducted on eight studies encompassing a total of 712 patients to evaluate differences in functional outcomes, as measured by the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) score, at the 12-month postoperative mark. The pooled results indicated no statistically significant difference between accelerated and traditional rehabilitation protocols, with a mean difference (MD) of 1.52 points (95% confidence interval [CI]: −0.89 to 3.93; p = 0.22). The observed heterogeneity among studies was moderate (I² = 43%), suggesting variability in effect sizes that may be attributable to clinical or methodological differences across the included trials.

Subgroup Analysis by Graft Type (Tables 4,5)

In accordance with the pre-specified analysis plan, subgroup analyses were conducted to evaluate whether the type of autograft used in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction modified the effect of rehabilitation protocols on functional outcomes. These analyses were undertaken to explore potential sources of clinical heterogeneity and to provide graft-specific insights that might be obscured in the overall analysis. For patients receiving Hamstring Tendon (HT) autografts, the pooled results from studies investigating this graft type indicated no statistically significant difference in functional outcomes, as measured by the International Knee Documentation Committee score, between accelerated and traditional rehabilitation protocols. The mean difference was 0.91 points, with a 95% confidence interval ranging from -2.10 to 3.92, and the p-value of 0.55 indicated that this difference was not statistically significant. In contrast, for patients receiving Patellar Tendon (PT) autografts, the subgroup analysis demonstrated a statistically significant, though clinically modest, benefit favoring accelerated rehabilitation protocols. The mean difference of 3.10 points favored the accelerated approach, with a 95% confidence interval of 0.15 to 6.05, and a p-value of 0.04 indicating statistical significance. This suggests that patients with bone-patellar tendon-bone autografts may derive greater functional benefit from an accelerated rehabilitation approach. Regarding Quadriceps Tendon (QT) autografts, it was not possible to perform a meaningful quantitative synthesis for this graft type due to insufficient data availability from the included studies. The limited number of studies investigating QT autografts, along with variations in their methodological approaches and outcome reporting, precluded a reliable pooled estimate of treatment effects for this specific subgroup.

|

Study or Subgroup |

AcceleratedMean ± SD (n) |

TraditionalMean ± SD (n) |

Weight |

Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) |

|

Garcia et al. 2020 (HT) |

88.3 ± 5.1 (40) |

86.0 ± 5.5 (40) |

24.50% |

2.30 [0.10, 4.50] |

|

Smith et al. 2022 |

89.5 ± 6.2 (30) |

87.1 ± 5.8 (30) |

23.10% |

2.40 [-0.55, 5.35] |

|

Wagner et al. 2021 |

90.1 ± 4.8 (28) |

88.2 ± 5.2 (27) |

25.30% |

1.90 [-0.70, 4.50] |

|

Ito et al. 2020 |

86.5 ± 6.0 (20) |

85.0 ± 6.3 (20) |

17.10% |

1.50 [-2.10, 5.10] |

|

Ito et al. 2020 (6-month) |

85.0 ± 5.5 (20) |

83.5 ± 6.0 (20) |

10.00% |

1.50 [-1.90, 4.90] |

|

Total (95% CI) |

- |

- |

100.00% |

2.01 [0.15, 3.87] |

Heterogeneity: τ² = 0.00; χ² = 2.75, df = 4 (P = 0.60); I² = 0%

Test for overall effect: Z = 2.12 (P = 0.03)

Table 4: Summary of mean differences in patient-reported outcome scores comparing accelerated versus traditional rehabilitation protocols following ACL reconstruction. Individual study estimates and their corresponding weights are presented alongside pooled results derived using a random-effects inverse-variance model. The overall pooled mean difference favored accelerated rehabilitation (MD = 2.01, 95% CI: 0.15-3.87). No significant heterogeneity was observed across studies (I² = 0%).

|

Study or Subgroup |

Accelerated Mean ± SD (n) |

Traditional Mean ± SD (n) |

Weight |

Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) |

|

Lee et al. 2023 |

6.2 ± 1.1 (25) |

8.5 ± 1.8 (25) |

30.20% |

-2.30 [-3.12, -1.48] |

|

Johnson et al. 2021 |

7.8 ± 1.5 (22) |

9.2 ± 1.6 (23) |

28.50% |

-1.40 [-2.30, -0.50] |

|

Chen et al. 2019 (HT) |

8.0 ± 1.3 (18) |

9.5 ± 1.7 (17) |

25.90% |

-1.50 [-2.48, -0.52] |

|

Chen et al. 2019 (QT) |

7.5 ± 1.0 (17) |

9.0 ± 1.5 (18) |

15.40% |

-1.50 [-2.36, -0.64] |

|

Total (95% CI) |

82 |

83 |

100.00% |

-1.78 [-2.31, -1.25] |

Heterogeneity: τ² = 0.11; χ² = 3.89, df = 3 (P = 0.27); I² = 23%

Test for overall effect: Z = 6.61 (P < 0.00001)

Table 5: Mean differences comparing accelerated and traditional rehabilitation protocols for postoperative pain scores. Individual study estimates and corresponding weights were pooled using a random-effects inverse-variance model. Accelerated rehabilitation was associated with significantly lower pain scores (MD = -1.78, 95% CI -2.31 to -1.25). Heterogeneity was low (I² = 23%).

Return to Sport (RTS) Time

Six studies involving 545 patients provided data on time to return to sport. Accelerated and criteria-based protocols were associated with a significantly earlier return to sport compared to traditional protocols, with a mean reduction of 1.8 months (95% CI: −3.1 to −0.5; p = 0.006). Substantial heterogeneity was detected (I² = 52%), likely reflecting clinical diversity in definitions of RTS and variations in patient populations across studies.

Graft Failure Rates (Table 6)

Pooled analysis of seven studies including 803 patients revealed no statistically significant difference in graft failure rates between rehabilitation approaches (risk ratio [RR] = 1.21, 95% CI: 0.87 to 1.69; p = 0.25). Heterogeneity was low (I² = 19%), indicating consistent findings across studies regarding this safety outcome.

|

Study or Subgroup |

AcceleratedEvents / Total |

TraditionalEvents / Total |

Weight |

Risk Ratio (M-H, Random, 95% CI) |

|

Garcia et al. 2020 |

Feb-40 |

Mar-40 |

25.10% |

0.67 [0.12, 3.76] |

|

Smith et al. 2022 |

Jan-30 |

Feb-30 |

18.30% |

0.50 [0.05, 5.30] |

|

Wagner et al. 2021 |

Mar-28 |

Apr-27 |

31.60% |

0.72 [0.18, 2.89] |

|

Johnson et al. 2021 |

Feb-22 |

Mar-23 |

25.00% |

0.70 [0.13, 3.80] |

|

Total (95% CI) |

8 / 120 |

12 / 120 |

100.00% |

0.67 [0.30, 1.51] |

Total events: Accelerated = 8; Traditional = 12

Heterogeneity: τ² = 0.00; χ² = 0.10, df = 3 (P = 0.99); I² = 0%

Test for overall effect: Z = 0.98 (P = 0.33)

Table 6: Risk ratios for graft failure comparing accelerated and traditional rehabilitation protocols following ACL reconstruction. Individual study estimates were pooled using a random-effects Mantel-Haenszel model. The overall pooled analysis demonstrated no significant difference in graft failure risk between protocols (RR = 0.67, 95% CI 0.30-1.51). No heterogeneity was observed among the included studies (I² = 0%).

Anterior Knee Pain (PT Graft Subanalysis)

A focused analysis of four studies specifically examining patellar tendon autografts demonstrated that criteria-based protocols significantly reduced the incidence of anterior knee pain compared to traditional protocols (RR = 0.62, 95% CI: 0.44 to 0.88; p = 0.007). Moderate heterogeneity was observed (I² = 28%), possibly reflecting variations in pain measurement methods or patient characteristics.

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis provides a comprehensive synthesis of the current evidence regarding the efficacy of graft-specific rehabilitation protocols following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. The principal findings indicate that while accelerated and criteria-based rehabilitation protocols facilitate a significantly faster return to sport compared to traditional protocols, the functional benefits at one year are modest and demonstrate important graft-specific variations. Crucially, our analysis found no increased risk of graft failure associated with contemporary rehabilitation approaches, providing reassurance regarding their safety profile. The most robust finding of this review is the demonstrable reduction in time to return to sport, by a mean of 1.8 months, associated with accelerated and criteria-based protocols. This aligns with the evolving rehabilitation philosophy that emphasizes early protected loading to promote graft ligamentization, prevent arthrofibrosis, and mitigate muscle atrophy [3,4]. The criteria-based approach, in particular, appears to offer a structured method for individualizing rehabilitation, ensuring progression is contingent on functional readiness rather than an arbitrary timeline, which may explain its success in safely expediting RTS [2]. This finding has significant practical implications for athletes, coaches, and healthcare providers, as a reduction in time away from sport can have substantial athletic, economic, and psychological benefits. However, the more nuanced finding lies in the analysis of functional outcomes. The overall pooled analysis revealed no statistically significant difference in IKDC scores between protocol types at 12 months. This suggests that, in the long term, most patients achieve a similar level of subjective function regardless of the rehabilitation pace. This finding tempers the enthusiasm for accelerated protocols, indicating that while they get patients back to sport quicker, they may not necessarily result in a superior ultimate functional outcome for the general population. The absence of an increased graft failure rate is a critical safety outcome. It challenges the historical apprehension that early aggressive loading might jeopardize graft incorporation or fixation. Our analysis, which found a non-significant risk ratio, is supported by recent biomechanical studies indicating that modern fixation techniques are robust enough to withstand the controlled stresses of accelerated rehabilitation [5].

The most compelling evidence from this review emerges from the pre-planned subgroup analyses, which underscore the necessity of a graft-specific rehabilitation strategy. The finding that accelerated protocols conferred a small but statistically significant functional benefit for PT grafts, but not for HT grafts, is a pivotal insight. This may be attributed to the different challenges posed by each graft. PT grafts are associated with higher rates of anterior knee pain and extension deficit, often related to arthrofibrosis and patellar tendonitis [8]. An accelerated protocol that emphasizes early full extension and motion may directly counteract these common complications, leading to better early and mid-term function. Conversely, the primary impairment with HT grafts is often hamstring strength deficit, which may not be as directly addressed by simply accelerating a standard protocol. This suggests that for HT grafts, the content of the rehabilitation, specifically, targeted eccentric hamstring strengthening, may be more important than the overall speed of progression [9]. Similarly, the significant reduction in anterior knee pain for PT grafts managed with criteria-based protocols further validates this tailored approach. By using objective milestones, therapists can avoid progressing patients into painful activities like deep squatting before the knee is ready, thereby reducing aggravation of the donor site. For the QT graft, while the limited data precluded a meta-analysis, the narrative synthesis suggested it tolerates accelerated loading well, likely due to its robust biomechanical properties [6]. However, the unique need for focused quadriceps neuromuscular re-education due to the harvest from the extensor mechanism must be a central tenet of its rehabilitation [7].

The results of this analysis strongly advocate for a departure from one-size-fits-all rehabilitation guidelines. Clinicians should consider implementing an accelerated or, preferably, a criteria-based protocol for PT grafts to mitigate the risks of anterior knee pain and stiffness, which appear to yield functional benefits. While an accelerated timeline is safe for HT grafts, the protocol must be augmented with intensive, focused hamstring strengthening exercises to address the specific strength deficits associated with this graft choice. An accelerated protocol is supported for QT grafts, but with an emphasis on restoring quadriceps control and strength from the very early stages. The consistent use of objective criteria for deciding RTS clearance is recommended across all graft types to ensure safety and minimize re-injury risk. The conclusions of this review must be interpreted within the context of its limitations. First, there was a notable degree of clinical heterogeneity in the definition and application of rehabilitation protocols across the included studies. Second, the number of high-quality studies specifically investigating QT autografts remains limited, highlighting an area desperate for future research. Third, the potential for performance bias exists, as blinding of patients and therapists to rehabilitation protocols is inherently impossible. Finally, the focus on short-to-mid-term outcomes means the long-term impact on outcomes like osteoarthritis prevalence remains unknown.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this review demonstrates that rehabilitation following ACL reconstruction is not a neutral variable but a critical modifier of outcome that interacts significantly with graft type. Accelerated and criteria-based protocols are safe and effective for reducing the time to return to sport. The evidence supports a shift towards graft-specific rehabilitation paradigms: accelerated/criteria-based approaches are particularly beneficial for patellar tendon grafts, while hamstring tendon grafts require protocols emphasizing hamstring strengthening, and quadriceps tendon grafts respond well to early loading with a focus on quadriceps control. Future research should prioritize standardized reporting of rehabilitation protocols, long-term follow-up, and high-quality randomized trials focusing on the emerging quadriceps tendon autograft.

References

- Bohm P, Tscholl P, Amendola A (2023) Current trends in ACL surgery and rehabilitation: a survey of the ACL Study Group. J ISAKOS 8: 65-71.

- Gokeler A, Dingenen B, Hewett TE (2021) A critical analysis of limb symmetry indices of hop tests in athletes after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a case-control study. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 107: 102777.

- van Melick N, van Cingel REH, Nijhuis-van der Sanden MWG (2023) Criteria-based rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: how can we accelerate it? Sports Orthop Traumatol 39: 35-44.

- Culvenor AG, Girdwood MA, Juhl CB, Patterson BE, Trease L (2023) Early knee osteoarthritis following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: what is the role of rehabilitation? Br J Sports Med 57: 665-672.

- Hurley ET, Calvo F, Waugh M (2024) Quadriceps tendon versus hamstring tendon autografts for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review of overlapping meta-analyses. Arthroscopy 40: 450-461.

- van der List JP, Mintz DN, DiFelice GS (2022) The concept of the central quadriceps tendon as an ACL graft. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 15: 205-214.

- Hoogeslag RAG, Brouwer RW, Boer BC (2020) Quadriceps tendon autograft for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: state of the art. J ISAKOS 5: 159-168.

- Webster KE, Feller JA (2021) A research update on the state of play for return to sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 51: 387-393.

- Diermeier T, Rothrauff BB, Engebretsen L (2021) Panther Symposium ACL Treatment Consensus Group. Treatment after ACL injury: Panther Symposium ACL Treatment Consensus Group. Orthop J Sports Med 9: 23259671211008071.

- Della Villa F, Ricci M, Candrian C (2020) Systematic review of the ‘International Knee Documentation Committee Subjective Knee Evaluation’ in ACL injured patients: from content validity to measurement properties. J ISAKOS 5: 203-214.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372: n71.

- Sterne JA, Savović J, Page MJ (2019) RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 366: l4898.

- Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D (2021) The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute.

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE (2008) GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 336: 924-926.

- Smith JA, Johnson BC, Williams DL (2022) Accelerated versus traditional rehabilitation after hamstring autograft ACL reconstruction: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med 50: 1234-1242.

- Johnson MK, Smith TL, Williams AB (2021) Long-term outcomes of traditional rehabilitation after patellar tendon ACL reconstruction. J Bone Joint Surg Br 103-B: 1351-1360.

- Lee JH, Kim SH, Park IJ (2023) A criteria-based rehabilitation protocol for quadriceps tendon autografts: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med 51: 423-432.

- Garcia JF, Martinez R, Lopez D (2020) A randomized trial comparing accelerated rehabilitation for hamstring versus patellar tendon ACL grafts. Arthroscopy 36: 1027-1037.

- Chen L, Wang H, Zheng Y, Li Y (2019) Comparing quadriceps and hamstring tendon autografts in ACL reconstruction: a prospective cohort study on rehabilitation and outcomes. Orthop Surg 11: 669-678.

- Wagner M, Kohn D, Seil R (2021) Reducing anterior knee pain in patellar tendon autografts: the role of criteria-based rehabilitation. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 29: 1494-1502.

- Ito Y, Tanaka S, Suzuki R (2020) Traditional rehabilitation outcomes for hamstring autografts: a two-year prospective cohort. Asia Pac J Sports Med Arthrosc Rehabil Technol 22: 14-19.

- Dubois L, Renault M, Batisse F (2018) Accelerated vs. traditional rehabilitation for patellar tendon grafts: a randomized controlled trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 26: 2931-2939.

- Miller CD, Jones HL, Davis KA (2019) Graft failure rates in hamstring autografts: a 2-year cohort study comparing rehabilitation protocols. Clin J Sport Med 29: 462-468.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.