A Unique Diagnostic Challenges of A Rare Case of Kaposi Sarcoma (KS) Originating in An Intra-Parotid Gland Lymph Node in A 69-Year-Old Male: Case Report and Literature Review

by Maram M. Fathi Ahmed1*, Eman M Algorashi2

1Radiological sciences department, Faculty of Applied medical sciences, Inaya Medical Collages, Al Qirawn, 11352, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

2Radiological sciences department, King's College Hospital London in Dubai, United Arab Emirates

*Corresponding author: Maram M. Fathi Ahmed, Radiological sciences department, Faculty of Applied medical sciences, Inaya Medical Collages, Al Qirawn, 11352, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Received Date: 25 September 2025

Accepted Date: 29 September 2025

Published Date: 01 October 2025

Citation: Ahmed MMF, Algorashi EM. (2025). A Unique Diagnostic Challenges of A Rare Case of Kaposi Sarcoma (KS) Originating in An Intra-Parotid Gland Lymph Node in A 69-Year-Old Male: Case Report and Literature Review. 10: 2424. https://doi.org/10.29011/2574-7754.102424

Abstract

Salivary Gland Kaposi Sarcoma (KS) are rare malignant of lymphatic endothelial origin. We present the case of a 69-year-old male who presented with a small painless lump in his left parotid region while shaving. A patient underwent an ultrasound after a small lump (about 1.7 cm) was found near the left parotid salivary gland. A follow-up MRI scan provided a more detailed view, showing a well-defined, solid mass measuring approximately 2.2 cm. The mass was located within the parotid gland but appeared separate from its deeper part. Its imaging characteristics led doctors to initially suspect common benign salivary gland tumors, like a pleomorphic adenoma or Warthin tumor. The mass was surgically removed. Analysis of the tissue after surgery revealed a surprising diagnosis: Kaposi sarcoma (a type of cancer often associated with the blood vessels) that was located inside a lymph node within the parotid gland. The tumor was successfully excised with clear margins. While this is most likely a rare case of Kaposi's sarcoma originating in the lymph node itself, the medical team noted that it is important to rule out the possibility that it could be a metastasis from another site, such as the skin. The patient is currently feeling well with no symptoms and will continue with regular clinical and radiological check-ups for ongoing monitoring. Early diagnosis and multidisciplinary treatment are essential to improve prognosis and survival rates.

Keywords: Kaposi sarcoma (KS); Salivary gland tumor; Parotid gland tumor; Lymphatic endothelial origin; Intra-parotid lymph node tumor

Introduction

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) presenting as a primary tumor within the salivary glands, particularly the parotid gland, is an exceptionally rare and diagnostically challenging occurrence. Its clinical and radiological features often mimic those of common benign salivary gland tumors, creating a significant risk of misdiagnosis and potentially delaying appropriate treatment. Kaposi Sarcoma (KS) is a multifocal neoplasm of lymphatic endothelial origin associated with Human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) infection [1]. It is categorized into four distinct clinical variants [2]. Classic Kaposi Sarcoma (CKS): Historically characterized as an indolent malignancy predominantly observed in elderly men of Mediterranean and Middle Eastern descent [3], with a male-to-female ratio of up to 15:1 [2]. It presents as multiple lesions on the distal extremities that progress slowly. Incidence shows significant geographic variation, being rare in North America but higher in endemic regions like rural Italy and Israel [3]. A significant gap exists in the literature regarding CKS in the U.S. and the United Arab Emirates [3]. Endemic Kaposi Sarcoma: Initially recognized in parts of Africa, it has an indolent form and an aggressive lymphadenopathic form that affects African children. Following the emergence of HIV/AIDS, distinguishing between HIV-negative endemic KS and HIV-associated epidemic KS became necessary [2]. Immunosuppression-Associated (Transplantation-Associated) Kaposi’s Sarcoma: This form occurs in iatrogenically immunosuppressed patients, such as organ transplant recipients, and is more prevalent in patients of Mediterranean, Middle Eastern, or African descent. It is often aggressive, with frequent visceral involvement [2]. Epidemic (AIDS-Associated) Kaposi’s Sarcoma: This aggressive variant emerged with the AIDS epidemic in 1981, affecting young homosexual men with severe immunodeficiency. It involves the skin, lymph nodes, mucosa, and visceral organs and remains the most frequently diagnosed AIDS-related malignancy in the United States [2]. The spread of HIV in Africa altered the pre-existing epidemiology of KS, increasing its incidence in previously uncommon regions and among women, suggesting additional cofactors beyond KSHV/HHV-8 are involved in pathogenesis [4].

While KS typically presents with cutaneous lesions, it can also occur in uncommon anatomical sites, posing diagnostic challenges [5]. Diagnosis is established through clinical and histological examination [1], and management aims for disease control using local modalities like radiotherapy for localized lesions [1]. This case report aims to describe the unique diagnostic challenges of a rare case of Kaposi sarcoma originating in an intra-parotid lymph node, Highlight the critical importance of using advanced imaging (MRI) and, ultimately, histopathological analysis to achieve a correct diagnosis when clinical presentation is atypical. And Emphasize the necessity of a multidisciplinary approach to rule out metastasis and to manage this unusual manifestation of KS effectively.

Case Presentation

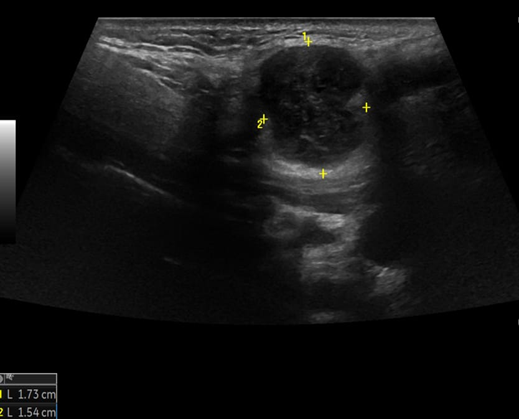

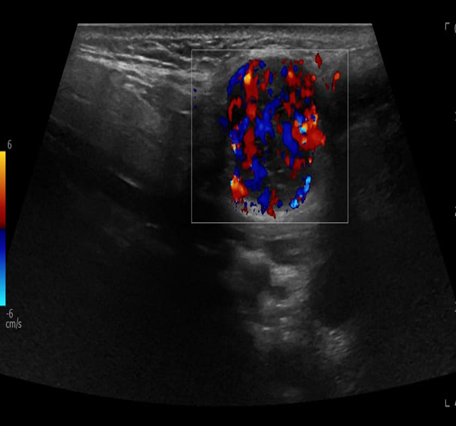

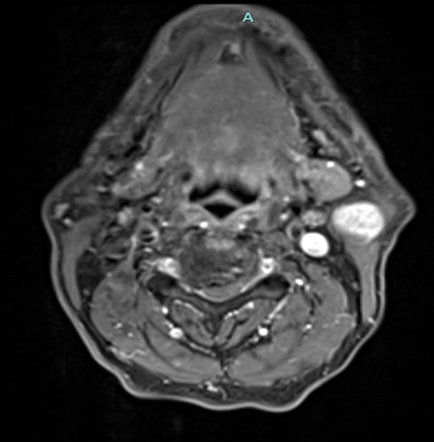

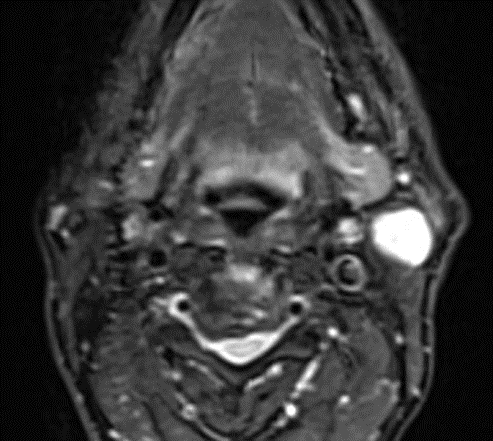

A 69-year-old male noticed a small painless lump in his left parotid region while shaving, Ultrasound examination of the area demonstrated a well-defined lesion measuring approximately 1.7x1.5 cm with internal vascularity, inseparable from the left parotid tail. The rest of the neck ultrasound was unremarkable; MRI was recommended to better define the lesion's origin before histopathological assessment. MRI revealed an oval-shaped, well-defined solid mass lesion in the left parotid gland, measuring about 2.2x1.9x1.3cm in maximum craniocaudally, transverse, and AP dimensions. The lesion is seen as separable from the deep part of the parotid gland, extending posteriorly, abutting the anterior aspect of the related sternomastoid muscle without definite muscle invasion. The lesion eliciting low signal in T1, heterogeneous low signal in T2 weighter images with heterogeneous post contrast enhancement. The main differential diagnoses considered were pleomorphic adenoma and Warthin tumor, although other possibilities could not be totally excluded. Surgical excision was performed. Histopathological analysis revealed Kaposi sarcoma within an intra-parotid lymph node. The lesion was excised with a margin of 0.5 cm. Although the findings were most consistent with a primary nodal Kaposi sarcoma, metastasis from other sites, particularly the skin, should be excluded (Table 1 and Figures 1-4).

The patient remains asymptomatic, and ongoing clinical and radiological follow-up has been advised.

|

Typical Anatomical Involvement In Kaposi Sarcoma |

Atypical Anatomical Involvement In Kaposi Sarcoma |

|

• Skin Oral mucosa • • Lymph nodes (superficial & deep) • Lungs, endobronchial tract, & pleura • Gastrointestinal tract • External genitalia • Oropharynx • Tonsils • Nasal cavity • Liver • Spleen • Bone marrow |

• Bones & skeletal muscles Peripheral nerves • Brain & spinal cord • Larynx • Eye & ear • Major salivary glands • Adrenal & thyroid gland • Heart • Thoracic duct • Kidney • Ureter & urinary bladder • Breast • Gonads • Pancreas • Wounds & blood clots |

Table 1: Typical and Atypical Anatomical Involvement in Kaposi Sarcoma.

Figure 1: Ultrasound of left parotid gland.

Figure 2: Ultrasound with color Doppler for left parotid gland.

Figure 3: MRI Finding of left parotid gland.

Figure 4: MRI Finding of left parotid gland.

Results

Surgical resection was performed and biopsy revealed Kaposi sarcoma within an intra- parotid lymph node, Regular follow- up was maintained during chemotherapy, and no major side effect was noted. A follow-up CT scan is scheduled after 3 months.

Discussion

First identified more than a century ago, Kaposi sarcoma is named for its discoverer, the Viennese dermatologist Moritz Kaposi (1837-1902), who published the initial description in 1872 [6]. Kaposi sarcoma is an uncommon cancer that affects blood vessels and can develop not just on the skin, but also in the mouth, lymph nodes, and internal organs like the lungs, liver, and digestive tract. The symptoms a person experiences depend greatly on where the tumors form and how widespread they are. This cancer is directly linked to infection by the Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV). However, getting this virus alone isn't enough to cause the cancer; a person's genetic makeup, environmental factors, and overall health also play a critical role. This is especially true for people living with HIV, whose weakened immune systems significantly increase the risk. Because of this, Kaposi sarcoma remains one of the most common cancers affecting the HIV community [7].

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a multifocal vascular tumor that can arise in any organ, though it most frequently presents on the skin and mucous membranes. Scientific interest in KS intensified dramatically with the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s, when its association with immunodeficiency became clear. The disease's etiologic agent, KSHV/HHV8, was identified by Chang et al. in 1994.

This pivotal finding established KS as a critical model for understanding fundamental cancer processes, including how viruses cause cancer (viral oncogenes), the formation of new blood vessels (angiogenesis), and the interaction between tumors and the immune system [8]. Kaposi's sarcoma (KS) is a vascular tumor that primarily presents on the skin and exists in four clinical variants. The most aggressive form is associated with HIV and often involves mucous membranes and internal organs. The disease has a striking geographic distribution, with approximately 75% of cases occurring in sub-Saharan Africa due to the high regional prevalence of its causative agent, Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV). KSHV infection leads to the transformation of endothelial cells. The virus employs a dual life cycle to promote cancer: its latent phase drives uncontrolled cell growth and blood vessel formation, while sporadic lytic reactivation produces proteins that further manipulate host cell signaling. A key feature of KS is its reliance on a supportive tumor microenvironment, where inflammatory cytokines and paracrine signaling foster tumor growth and survival. KSHV also actively evades the immune system by degrading protective proteins and interfering with immune signaling. While chemotherapy is a standard treatment, current research is focused on developing novel therapies that target these unique viral and immunological mechanisms. [9] Kaposi's sarcoma (KS) is a multifocal malignancy of lymphatic endothelial cell origin. While its most common manifestations are cutaneous and mucosal, the disease can also involve the lymphatic system and visceral organs, including the gastrointestinal tract, lungs, and liver. Clinically, KS is categorized into five distinct epidemiological subtypes, each with a unique clinical course and prevalence within specific populations: Classical KS, Iatrogenic KS, associated with immunosuppressive therapy, Endemic (African) KS, including a lymphadenopathy form, Epidemic, HIV-associated KS, which includes KS manifesting as part of Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome (IRIS) KS in HIV-negative men who have sex with men (MSM) This is based on an interdisciplinary guideline that consolidates current, evidence-based recommendations for the diagnosis and management of these various KS forms. [10] A strong case exists for prioritizing the development of both preventative and therapeutic vaccines against Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV). The need is underscored by the virus's transmission patterns; in endemic areas, transmission during childhood is efficient, leading to seroconversion rates exceeding 80% by adolescence, a dynamic similar to other herpesviruses. [11] Kaposi's sarcoma (KS) has become one of the most frequent skin cancers in two primary populations: transplant recipients in Mediterranean regions and young unmarried men affected by the HIV/AIDS epidemic. The development of KS is linked to infection with the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), also known as human herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8). The incidence of the disease follows a distinct geographic pattern, increasing from Nordic countries to sub-Saharan Africa, which mirrors the rising prevalence of HHV-8 infection in those regions.

Understanding that KS pathogenesis involves both viral infection and immunosuppression is critical. This knowledge allows for the identification of at-risk individuals (such as those who are HHV-8 seropositive), guides the monitoring of immune function in patients on immunosuppressive therapy, and informs the development of novel treatments that target the virus or modulate the immune response. [12] Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a complex neoplasm with a highly variable clinical presentation, ranging from indolent cutaneous lesions on the lower extremities to widespread, aggressive disease involving multiple internal organs. Long before the HIV epidemic, a high incidence of the disease, including in children, was well-documented in parts of East and Central Africa.

Following the emergence of HIV/AIDS, the incidence of this previously rare tumor in Western nations surged, making it a common AIDS-defining illness. However, careful epidemiology revealed its distribution was not uniform among all HIV-positive groups. It was most prevalent in men who have sex with men but was exceptionally rare in other groups, such as hemophiliacs or women who contracted HIV through contaminated blood products. This disparate pattern suggested KS was caused by a separate infectious agent, transmitted independently of HIV through specific routes, likely sexual. This hypothesis spurred a successful search for the causative pathogen, culminating in the identification of a novel herpesvirus now known as Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus in tumor biopsies from AIDS patients in 1994. [13] Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus is primarily transmitted through saliva. Its higher prevalence among men who have sex with men also indicates that sexual transmission represents another significant route of infection. [14] While a clinical presentation can strongly suggest Kaposi sarcoma (KS), recent studies have shown that visual diagnosis alone is often unreliable. Histopathological examination remains the definitive diagnostic method. However, this process can be challenging, particularly for early-stage lesions where subtle microscopic features are easily overlooked by an untrained eye. In contrast, well-developed KS lesions typically display more characteristic histopathological patterns that allow for a confident diagnosis by an experienced pathologist. [15] This was also observed in certain groups of homosexual men living with AIDS. [16] The precise cellular origin of Kaposi sarcoma lesions remains unclear, which significantly hinders a comprehensive understanding of the disease's biology.

[17] The development of classic Kaposi sarcoma is influenced by a complex array of causative and disease-promoting factors. The interaction between these various elements has made it difficult to determine how the disease is initiated and progresses, as well as to define the individual role of each factor. Similar to other human DNA viruses that cause cellular transformation, infection with Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV/HHV8) by itself is insufficient to cause KS, indicating that additional cofactors are necessary for the disease to manifest. [18] Kaposi's Sarcoma presents a fascinating window into how viruses can contribute to human cancer. The disease doesn't strike randomly; its distinct geographical patterns and tendency to appear in clusters strongly suggest that a complex interplay of genetics, environment, and infection is at work.

The mystery deepens when we consider people. The disease is very rare within families, yet it is strikingly common in specific endemic regions and ethnic groups. This paradox challenges a simple explanation. While it clearly isn't inherited in a straightforward way, these patterns still leave open the compelling possibility that some individuals may have an inherited genetic susceptibility that makes them more vulnerable to developing the disease. [19] Recent data reveals a deeply concerning health disparity: a few specific cancers are responsible for stealing the most years of life from people living with HIV (PLWH) in the United States. These include non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Kaposi's sarcoma, HPV-associated anal cancer, and lung cancer. The burden of these diseases falls disproportionately on Black Americans with HIV, gay and bisexual men, and individuals in their 40s and 50s, highlighting a critical area where focused care and support are urgently needed. [20] For individuals living with AIDS, the risk of developing certain cancers is significantly high, with nearly 40 percent of patients affected. The most common of these are Kaposi’s sarcoma and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. A pivotal study by Chang and colleagues provided a major breakthrough by uncovering evidence of an infectious cause for Kaposi’s sarcoma, a finding that supported earlier clues from epidemiological research [21, 22].

The team discovered two new DNA fragments that were present in over 90 percent of Kaposi’s sarcoma tissue samples taken from AIDS patients, yet were entirely absent in samples from people without AIDS. Intriguingly, these same genetic fragments were also detected in a small number of other tissues from AIDS patients, including several lymphomas, suggesting the infectious agent might be involved in more than one type of illness.

Conclusion

The patient successfully underwent surgery to remove the tumor, which was identified as a rare form of cancer called Kaposi's sarcoma located within a salivary gland lymph node. The surgeons were able to remove it completely with clear margins. Their chemotherapy treatments were closely monitored, and they tolerated them very well without experiencing any major side effects. The patient currently feels well and has no symptoms. While the evidence suggests this cancer originated in the lymph node, the care team is taking a thorough approach by ensuring it did not spread from another area, such as the skin. To monitor their health closely, the patient will continue with regular check-ups, which will include a CT scan in three months.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the participant for his cordial support, and king’s college hospital Dubai for their technical service.

Informed Consent

Informed written consent was taken from the patient to publish this case report and any accompanying images in accordance with the journal's patient consent policy.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Lebbe C, Garbe C, Stratigos AJ, Harwood C, Peris K. (2019). Diagnosis and treatment of Kaposi’s sarcoma. European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline (EDF/EADO/EORTC). Eur J Cancer. 114: 117-127.

- Karen Antman, Chang Y. (2010). Kaposis Sarcoma. N Engl J Med. 342: 1027-1038.

- Hiatt KM, Nelson AM, Lichy JH, Fanburg-Smith JC. (2008). Classic Kaposi Sarcoma in the United States over the last two decades: a clinicopathologic and molecular study of 438 non-HIV-related Kaposi Sarcoma patients with comparison to HIV-related Kaposi Sarcoma. Mod Pathol. 21: 572-582.

- M Dedicoat, Newton R. (2003). Review of the distribution of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) in Africa in relation to the incidence of Kaposi’s sarcoma. British Journal of Cancer. 88: 1-3.

- Pantanowitz L, Dezube BJ. (2008). Kaposi sarcoma in unusual locations. BMC Cancer. 8: 190.

- Kaposi. (1872). Idiopathisches multiples Pigmentsarkom der Haut. Archiv für Dermatologie und Syphilis. 4: 265-273.

- Fu L, Tian T, Wang B, Lu Z, Gao Y, et al. (2023). Global patterns and trends in Kaposi sarcoma incidence : a population-based study. Lancet Glob Health. 11: E1566-e1575.

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. (2013). Kaposi Sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 137: 289-294.

- Karabajakian A, Ray-Coquard I, Jean-Yves B. (2022). Molecular Mechanisms of Kaposi Sarcoma Development. Cancers. 14: 1869.

- Esser S, Schofer H, Hoffman C, Claßen J, Kreuter A. (2022). S1 Guidelines for the Kaposi Sarcoma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 20: 892-904.

- Dittmer DP, Damania B, (2016). Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus: immunobiology, oncogenesis, and therapy. J clin Invest. 126: 3165-3175.

- FM Buonaguro, ML Tornesello, L Buonaguro, RA Satriano, E Ruocco. (2003). Kaposi’s sarcoma: aetiopathogenesis, histology and clinical features. JEADV. 17: 138-154.

- Mariggio G, Koch S, Schulz TF. (2017). Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus pathogenesis. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. 372: 20160275.

- Whitby TS, Uldrick TS. (2011). Update on KSHV epidemiology, Kaposi Sarcoma pathogenesis, and treatment of Kaposi Sarcoma. Cancer Lett. 305: 150-162.

- Schneider JW, Dittmer DP. (2017). Diagnosis and Treatment of Kaposi Sarcoma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 18: 529-539.

- Moore PS, Chnag Y. (1995). Detection of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in Kaposi's sarcoma in patients with and those without HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 332: 1181-1185.

- Hsei-Wei W, Trotter MWB, Lagos D, Bourboulia D, Henderson S. (2004). Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus-induced cellular reprogramming contributes to the lymphatic endothelial gene expression in Kaposi sarcoma. Nat Genet. 36: 687-693.

- Iscovich J, P Boffetta, S Franceschi, E Azizi, R Sarid. (2000). Classic Kaposi Sarcoma Epidemiology and Risk Factors. Cancer. 88: 500-517.

- B Safai, R A Good. (1981). Kaposi's sarcoma: a review and recent developments. CA Cancer J Clin. 31: 2-12.

- Damania B, Dittmer DP. (2023). Today’s Kaposi Sarcoma is not the same as it was 40 years ago, or is it? J Med Virol. 95: e28773.

- E Cesarman, Y Chang, PS Moore, JW Said, DM Knowles. (1995). Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-related body-cavity-based lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 332: 1186-1191.

- Pantanowitz L, Grayson W. (2008). Histological variants of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma. Diagnostic Pathology. 3: 31.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.