A Rare Case of ‘Amyand’s Hernia’

by E. Caruso1, R. Pellegrino1, V. Tedesco2; Carmine Gabriele1, G. Gambardella3, L. Strangis1; F. Ibba1, M. Tedesco and D. Gambardella1*

1Department of General Surgery, G. Paolo II Hospital, Lamezia Terme, Italy

2Department of Medical and Surgical Sciences, University of Plovdiv, Bulgaria

3Department of Medical and Surgical Sciences, University of Catanzaro, Catanzaro, Italy

*Corresponding author: Denise Gambardella, Department of General Surgery, G. Paolo II Hospital, Lamezia Terme, Italy

Received Date: 22 September 2025

Accepted Date: 26 September 2025

Published Date: 29 September 2025

Citation: Caruso E, Pellegrino R, Tedesco V, Gabriele C, Gambardella G, et al. (2025) A Rare Case of ‘Amyand’s Hernia’. J Surg 10: 11456 https://doi.org/10.29011/2575-9760.011456

Abstract

Amyand’s hernia is a rare condition characterized by the presence of the vermiform appendix within an inguinal hernia. We present the case of a 54-year-old male patient with a known right inguinal hernia managed conservatively, who presented with acute abdominal pain. The preoperative diagnosis was complicated by the absence of specific signs of appendicitis on imaging; however, surgery revealed an inflamed appendix trapped within the hernial sac. The patient was successfully treated with appendectomy and hernia repair using the Trabucco technique and a 3D prolene patch.

Introduction

Amyand’s hernia is a rare form of inguinal hernia first described in 1735 by Claudius Amyand. Its incidence is less than 1% of all inguinal hernias, and preoperative diagnosis is often challenging due to the nonspecific clinical presentation [1]. Although acute appendicitis associated with this condition is rare, preoperative diagnosis can be challenging due to nonspecific symptoms and difficulty in identifying the appendix within the hernial sac [2,3]. The pathophysiology of Amyand’s hernia remains unclear, with various theories proposed to explain its development. The most widely accepted theory involves primary appendiceal inflammation causing edema and bacterial superinfection, while another suggests that mechanical trauma during incarceration results in inflammation, which leads to a vicious cycle of compromised blood supply and exacerbation of symptoms [4]. In addition, several studies have reported cases across a broad range of ages, from infants to the elderly, with a slight male predominance [5,6]. This case highlights the importance of considering this rare entity in the differential diagnosis of a symptomatic inguinal hernia, especially in patients with a history of abdominal surgery. In this case report, we describe a patient with an incarcerated right inguinal hernia who developed acute appendicitis, with diagnosis confirmed only during surgery.

Case Presentation

History: A 54-year-old male patient in apparent good health. History includes laparoscopic cholecystectomy six years prior and chronic antihypertensive treatment. Known to have a right inguinal hernia diagnosed approximately two years ago and managed conservatively. He works as a warehouseman, lifting heavy loads.

Clinical Presentation

The patient presented to the emergency department with acute abdominal pain. On physical examination, a positive Blumberg sign was noted.

Laboratory Tests

Mild neutrophilic leukocytosis and minimal alteration in CK and LDH.

Imaging

Abdominal CT scan showed a right inguinal hernia containing an intestinal loop, with no description of the cecal appendix. While CT and ultrasound are valuable diagnostic tools, they may fail to detect an inflamed appendix within the hernia sac, as demonstrated in previous reports [7,8].

Diagnosis and Treatment

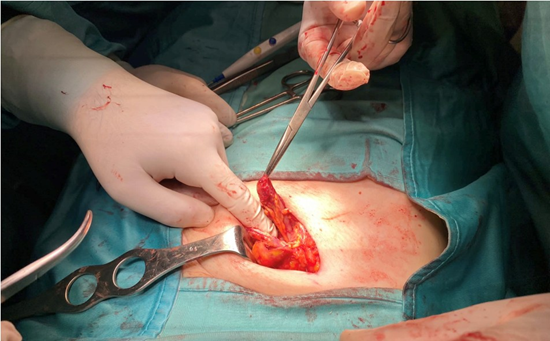

Although imaging did not show specific signs of appendicitis, the clinical presentation suggested the need for urgent surgical intervention. During laparotomic surgery, an inflamed appendix incarcerated within the hernial sac was found, confirming the diagnosis of Amyand’s hernia (Figure 1). Appendectomy was performed, and hernia repair was carried out using the Trabucco technique, with the application of a 3D prolene patch. The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful.

Figure 1: Inflamed appendix incarcerated within the hernial sac.

Literature Review and Discussion

Amyand’s hernia is a rare diagnosis, with an incidence of less than 1% of all inguinal hernias. A similar clinical case was reported by Lippolis et al. in 2007, describing an Amyand’s hernia in an adult patient with a diagnosis of appendicitis confirmed only during surgery. The laparoscopic surgical approach is often preferred for combined management of the appendix and hernia defect [4]. Amyand’s hernia is a rare diagnosis, with an incidence of less than 1% of all inguinal hernias. A similar clinical case was reported by Lippolis et al. in 2007, describing an Amyand’s hernia in an adult patient, with a diagnosis of appendicitis confirmed only during surgery. The laparoscopic surgical approach is often preferred for the combined management of the appendix and the hernia defect [4]. Finding the vermiform appendix within an inguinal hernia, although rare, is not uncommon, occurring in about 1% of inguinal hernia cases [5]. However, acute appendicitis associated with incarceration or strangulation is much less common, with an estimated incidence of 0.13% [6]. The pathophysiology of Amyand’s hernia remains unclear, with two main theories: the first suggests that primary appendiceal inflammation causes edema and bacterial superinfection, while the second theory posits that the appendix undergoes mechanical trauma during incarceration, leading to an inflammatory reaction and a vicious cycle that compromises blood supply, exacerbating the inflammation [7,8]. According to Abu-Dalu, Logan, Hennington, Apostolidis, and Papadopoulos, periappendicitis and vascular congestion are common findings when the appendix is trapped in a hernial sac, which supports the second theory [9-13]. Preoperative diagnosis of Amyand’s hernia remains difficult and can only be achieved with a high index of suspicion. Weber, who reviewed 60 cases over 40 years, found that only one case was accurately diagnosed preoperatively [5]. This rarity of accurate preoperative diagnosis highlights the importance of maintaining a broad differential diagnosis when evaluating inguinal hernias with atypical presentations. The use of imaging techniques, including ultrasound and CT, can aid in the identification of Amyand’s hernia. However, their utility is often limited, as in our case, where CT imaging failed to visualize the appendix within the hernial sac. Akifirat and Celik reported cases where ultrasound successfully identified the appendix within the hernia sac [7]. The treatment of Amyand’s hernia includes appendectomy with hernia repair. When inflammation or perforation is present, synthetic mesh is usually avoided to reduce the risk of infection [6,8]. An approach often recommended is to open the hernial sac to inspect the contents, particularly in cases where Amyand’s hernia is suspected. Failing to do so may result in delayed diagnosis and treatment, which could worsen the patient’s prognosis [9]. Several authors suggest that acute appendicitis within a hernial sac can present with episodic, cramp-like pain rather than the dull, constant pain typically seen in intestinal strangulation. Fever and leukocytosis may not always be present, which further complicates the diagnosis [10,11]. Patients generally seek medical attention when the inflammatory phase is advanced, and thus the medical history and physical examination often focus on the presence of a painful swelling above a preexisting hernia, often leading to a diagnosis of incarceration or strangulation, even if clinical and radiological signs of intestinal obstruction are lacking [9].

An important observation is that some authors report episodic, cramp-like pain rather than the constant pain typically seen in intestinal strangulation. Also, fever and leukocytosis are not always reliable symptoms for this diagnosis [12,13]. Nevertheless, some cases may present with typical prodromes of appendicitis with epigastric or periumbilical pain that then localizes to the lower right quadrant or the hernial sac [6]. In recent clinical cases, a reduced number of complications has been recorded, including 11456 DOI: 10.29011/2575-9760.011456

pneumonia, epididymitis, and urinary retention, suggesting that a better understanding of the clinical picture may further improve prognosis [10]. Overall, the prognosis of Amyand’s hernia is generally favorable with early recognition and appropriate surgical management. However, delayed diagnosis or inadequate treatment can result in complications such as peritonitis, abscess formation, and sepsis [6,9,12]. Additionally, it is important to mention that several studies have reported cases across a broad range of ages, from infants to the elderly, with a slight male predominance [1,3,5]. A historical perspective reveals that appendicitis occurring within an inguinal hernia was documented as early as 1735 by Claudius Amyand, who performed the first successful appendectomy [2]. Authors like Abu-Dalu, Logan, Hennington, Apostolidis, and Papadopoulos have reported cases where periappendicitis and vascular congestion were commonly found when the appendix was incarcerated in a hernial sac [10-13]. This supports the second theory that mechanical trauma during incarceration may play a significant role in the inflammatory process.

Conclusions

The described case highlights the rarity of Amyand’s hernia and the diagnostic difficulty associated with this condition. High clinical suspicion and timely surgical intervention are essential for the proper management of this pathology. Although preoperative diagnosis can be challenging, the laparoscopic approach and hernia repair with a 3D prolene patch proved effective in treating this rare condition, with a favorable outcome for the patient. Knowledge of the pathophysiology and differential diagnosis of Amyand’s hernia is crucial to improve prognosis and reduce the risk of postoperative complications.

References

- Deaver JB (1905) Appendicitis. Philadelphia: Blackiston’s Son & Co.

- Creese PG (1953) The first appendicectomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet 97: 643-652.

- Shepherd JA (1954) Acute appendicitis. A historical survey. Lancet 2: 299-302.

- D’Alia C, Lo Schiavo MG, Tonante A (2003) Amyand’s hernia: case report and review of the literature. Hernia 7: 89-91.

- Lyass S, Kim A, Bauer J (1997) Perforated appendicitis within an inguinal hernia: case report and review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol 92: 700-702.

- Thomas WEG, Vowles KDJ, Williamson RCN (1982) Appendicitis in external herniae. Ann R Coll Surg 64: 121-122.

- Carey LC (1967) Acute appendicitis occurring in hernias: A report of 10 cases. Surgery 61: 236-238.

- Davies MG, O’Byrne P, Stephens RB (1990) Perforated appendicitis presenting as an irreducibile inguinal hernia. Br J Clin Pract 44: 494495.

- El Mansari, Sakit F, Janati MI (2002) Acute appendicitis on crural hernia. Presse Med, 2002; 31 (24): 1129-1130.

- Abu-Dalu J, Urca I (1972) Incarcerated inguinal hernia with a perforated appendix and periappendicular abscess. Dis Colon Rectum 15: 464-465.

- Logan MT, Nottingham JM (2001) Amyand’s hernia. A case report of an incarcerated and perforated appendix within an inguinal hernia and review of literature. Am Surg 67: 628-629.

- Hennington MH, Tinsley EA, Proctor HJ (1991) Acute appendicitis following blunt abdominal trauma, incidence or coincidence? Ann Surg 214: 61-63.

- Apostolidis S, Papadopoulos V, Michalopoulos A (2005) Amyand’s Hernia: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. The Int J Surg 6: 1.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.