A Primer on Cardiovascular Disease and Air Travel: Practical Guidance for Frontline Clinicians

by Dawlat Khan1*, Dawood Shehzad2, Haddaya Umr2, Zain Saeed Alzahrani4, Bilal Jamshaid3, Fnu Abubakar2, Hammad Chaudhry1

1Clinic Assistant Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Sanford School of Medicine, University of South Dakota, USA

2Resident, Department of Internal Medicine, Sanford School of Medicine, University of South Dakota, USA

3Phoenixville Hospital - Tower Health, Phoenixville, Pennsylvania, USA

4 Hospitalist, Winchester Medical Centre, Virginia, USA

*Corresponding author: Dawlat Khan, Clinical Assistant Professor of Medicine, Sanford School of Medicine- University of South Dakota, 1305 W 18th Street, Sioux Falls, SD- 57105, USA

Received Date: 16 January, 2026

Accepted Date: 24 January, 2026

Published Date: 28 January, 2026

Citation: Khan D, Shehzad D, Umr H, Saeed Alzahrani Z, Jamshaid B, Abubakar F, et al. (2026) A Primer on Cardiovascular Disease and Air Travel: Practical Guidance for Frontline Clinicians. J Family Med Prim Care Open Acc 10: 292. https://doi.org/10.29011/2688-7460.100292

Abstract

The growing prevalence of cardiovascular disease, advanced cardiac therapies, and heart transplantation has resulted in an increasing number of patients seeking medical advice regarding air travel safety. Clinicians are frequently asked to assess fitness to fly, yet practical guidance remains fragmented across cardiology and aviation medicine sources. This primer provides a clinically focused overview of cardiovascular considerations during commercial air travel, including key physiological stressors, common in-flight cardiovascular events, and condition-specific travel considerations. Emphasis is placed on practical pre-travel assessment, identification of contraindications, and recognition of situations requiring specialist referral, to support safe, informed decision- making in routine clinical practice.

Keywords: Air travel; Hypobaric hypoxia; Cardiovascular disease; Chronic heart failure; Cardiac arrhythmias; Cardiac implantable electronic devices; Mechanical circulatory support; Heart transplantation; Travel medicine

Introduction

Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) affects about 523 million people worldwide and causes roughly 18.6 million deaths each year [1]. Over recent decades, the prevalence of CVD has increased globally, leading more individuals with chronic heart conditions to travel by air. An estimated 1.5 to 4.5 billion airline passengers each year [2], many travellers have underlying cardiovascular issues and might be exposed to flight-related physiological stressors such as hypobaric hypoxia and sympathetic activation. The incidence of in-flight medical emergencies has been evaluated in large observational studies involving 744 million airline passengers. Approximately 1.6 per 100,000 passengers required in-flight medical assistance. Cardiovascular presentations predominated, with syncope or near-syncope accounting for 32.7% of events, followed by other cardiovascular symptoms (7.0%). Although in-flight deaths were rare, 31 of 36 fatalities were attributable to cardiovascular causes, most commonly cardiac arrest [3].

In parallel, the use of advanced cardiovascular therapies has expanded considerably. In the United States, about 200,000 permanent pacemakers and more than 300,000 Cardiac Implantable Electronic Devices (CIEDs) are implanted each year [4,5]. Additionally, in the last decade (2013-2022), 27,493 patients were supported with continuous-flow Left Ventricular Assist Devices (LVADs), forming one of the largest contemporary cohorts of patients receiving durable mechanical circulatory support [6], and a total of 4,000 heart transplants occurred in 2023 alone [7].

As more patients with advanced cardiovascular disease, advanced cardiac therapies, and heart transplants resume routine daily activities, including air travel, primary care and family physicians are increasingly asked to advise on travel safety. This review provides a practical overview of cardiovascular risks associated with air travel, outlines pre-travel assessment and counseling strategies suitable for outpatient practice, and highlights situations in which referral to cardiology or transplant specialists is recommended.

Physiological Impact of Cabin Altitude on Oxygenation and Gas Exchange

At higher altitudes, barometric pressure decreases, reducing the partial pressure of inspired oxygen (PiO₂). Although commercial aircraft cruise at 30,000-40,000 feet, cabin pressurization maintains an equivalent altitude of up to 8,000 feet, as required by the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration [8]. At this altitude, PiO₂ falls from approximately 150 mmHg at sea level to 110-125 mmHg [9], resulting in lower arterial oxygen tension and potential hypoxemia in susceptible individuals [10].

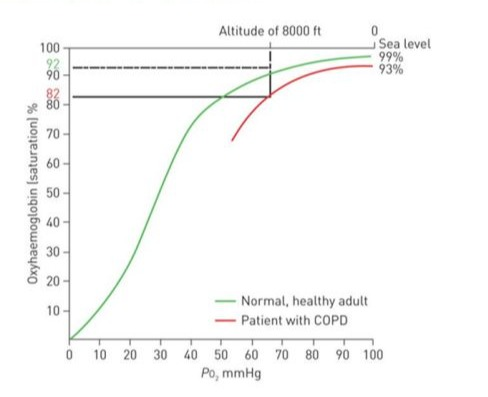

In healthy travellers with normal cardiorespiratory reserve and a sea-level PaO₂ above 95 mmHg, this shift moves the individual along the flatter portion of the oxyhaemoglobin dissociation curve (Figure 1) [11]. The result is typically a modest 3-4% fall in arterial oxygen saturation, which is usually well tolerated and often asymptomatic [12]. However, patients with cardiovascular disease, particularly those with heart failure or limited cardiac reserve, may experience clinically significant effects, including dyspnea, chest discomfort, palpitations, fatigue, light-headedness, or reduced exercise tolerance, due to hypoxemia and increased sympathetic activation during flight [3].

Figure 1: Oxyhemoglobin dissociation curve illustrating the effects of altitude-related hypoxia in healthy individuals versus patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD). PO₂: partial pressure of oxygen. Adapted from [11] with permission.

Disease-Specific Considerations for Cardiovascular Diseases During Air Travel

According to guidelines and consensus among various aviation societies and authorities, certain cardiovascular conditions are considered absolute contraindications for air travel. These conditions carry significant risks to individuals’ health and safety during the flight, highlighting the need for a thorough evaluation before travel [13]. Cardiovascular conditions are absolute contraindications to air travel (Table 1) [14].

|

Category |

Conditions |

|

Coronary Artery Disease (CAD) |

1. Uncomplicated myocardial infarction (MI) or CABG within 2 weeks. 2. Complicated MI within 6 weeks 3. unstable angina. |

|

Pump (Heart Function) |

|

|

Rhythm Disturbances |

ventricular or supraventricular arrhythmias(uncontrolled) |

|

Aortic Conditions |

Stanford Type A aortic dissection-unrepaired |

|

This table summarizes cardiac conditions in which air travel is absolutely contraindicated due to high risk of in-flight deterioration. Air travel should be deferred until stabilization and cardiology clearance. (Abbreviations: CAD: Coronary Artery Disease; MI: Myocardial Infarction; CABG: Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting; EF: Ejection Fraction; ICD: Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator) |

|

Table 1: Absolute Contraindications to Air Travel in Cardiac Patients.

Ischemic Heart Disease (IHD)

Ischemic heart disease (IHD) is the most common cause of in-flight medical emergencies, largely due to its high prevalence in the general population. Aerodynamic stressors can act as triggers that worsen the condition [15]. The IHD disease is classified into a) chronic coronary syndrome and b) acute coronary syndrome, which have somewhat different air travel recommendations.

Chronic Coronary Syndrome

Often referred to as stable coronary disease, these conditions usually present as angina [16]. Leading U.S. and European societies (ACS/ ESC) do not recommend pre-flight stress testing for stable CCS. However, if new ischemic symptoms appear or existing symptoms worsen despite treatment, a thorough evaluation is necessary [17]. In cases of stable CAD, fitness for air travel is evaluated based on the severity of angina, the complexity of elective angioplasty, and the stability of the patient following CABG surgery. When CAD is stable, patients are considered fit for air travel depending on the severity of angina, the intricacy of elective angioplasty, and their stability after CABG (Table 2) [14,17].

|

Medical condition |

Recommendations |

|

Angina |

|

|

CCS-I-II* |

Optimized for flight |

|

Angina CCS-III |

In-flight supplemental oxygen and airport assistance |

|

Angina-VI |

Unfit for travel |

|

Stable CAD post-elective angioplasty |

|

|

Simple angioplasty |

Fit to fly 48-72 hours. |

|

uncomplicated angioplasty** |

5-7 days |

|

Complicated*** |

Unfit for flight, specialist consultation. |

|

Post CABG-stable |

|

|

When no symptoms, hemodynamically and electrically stable, and wound healing is well |

Fit to fly after 10-14 days. |

|

*Canadian Cardiovascular Society grading of angina pectoris; **Multiple stents, left main stenting, coronary artery bifurcation stent; ***Dissection, perforation, and access problem, hematoma/bleeding |

|

|

This table outlines fitness-to-fly guidance for patients with stable angina, recent coronary interventions, or post–Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting (CABG). Decisions are based on symptom severity, procedure complexity, hemodynamic stability, and the presence of complications. (Abbreviations: CAD: Coronary Artery Disease; CCS: Canadian Cardiovascular Society; CABG: Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting) |

|

Table 2: Air Travel Recommendations for Patients with Chronic Coronary Artery Disease.

Acute Coronary Syndrome

Acute Coronary Syndromes (ACS) include Unstable Angina Pectoris (UAP), non-ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction (NSTEMI), and ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI) [18]. In the immediate aftermath of these events, patients face an increased risk of postinfarct complications, which heightens their risk for air travel [19]. Recommendations for air travel following ACS are primarily based on theoretical insights into in-flight stressors, given the significant lack of robustly powered studies on cardiovascular safety in this context [20]. The evolving perceptions of risk have prompted more lenient guidelines for permitting air travel after ACS events, exemplified by the American College of Cardiology’s decision to remove guideline statement concerning post-NSTEMI air-travel [21]. Recognizing that not all ACS patients are alike, it is a sensible approach to utilize selected nonmodifiable clinical predictors in conjunction with appropriate risk calculators, such as the Zwolle risk score, to customize risk stratification for evaluating flying fitness post-ACS [14,2224] (Table 3).

|

Clinical Scenario |

Criteria/Details |

Travel Recommendations |

|

Post ACS |

||

|

Uncomplicated * |

Asymptomatic, EF ≥50, Age ≤65, No mechanical/electrical complications |

|

|

Mild complication |

Mild symptoms 40-50% |

Can fly 10-14 days |

|

Moderate complications |

Moderate symptoms, EF <40% |

airport assistance/medical escort |

|

Severe complications |

Unresolved mechanical/electrical complications** |

Unfit for air travel, specialist consultations |

|

Post-CABG after ACS |

||

|

Post-Op Stable |

Asymptomatic, hemodynamically/electrically stable and no wound complication |

Fly in 10-14 days |

|

Post-Op Unstable |

Moderate symptoms, EF<40 |

Unfit for flight, cardiology and aviation team review |

|

*Must meet all conditions; **VT/VF, atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular rate, high-grade heart block. |

||

|

This table summarizes clinical scenarios and fitness-to-fly timelines for patients recovering from ACS, including those managed medically, post– angioplasty, or post–coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). Travel recommendations are based on symptom severity, left ventricular function, and the presence of mechanical or electrical complications. (Abbreviations: ACS: Acute Coronary Syndrome; EF: Ejection Fraction; VT: Ventricular Tachycardia; VF: Ventricular Fibrillation; CABG: Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting) |

||

Table 3: Air Travel Recommendations Following Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS).

Heart Failure, Valvular Heart Disease, and Cardiomyopathies

Overall, heart failure, valvular disease, and various cardiomyopathies follow similar recommendations and assessments related to air travel [25]. Patients who are functionally stable with heart failure (NYHA Class I and II) in the 4-6 weeks before flying, including those with significant left ventricular systolic impairment, can tolerate mild hypoxia in the aircraft cabin and are considered fit to travel [26]. However, acute heart failure decompensation or recent hospitalization pose a significant risk for travel, requiring a careful assessment and optimization of cardiac status before confirming fitness to fly. All triggers of acute decompensation should be addressed, and patients should be monitored for clinical stability over 6-8 weeks after discharge, with Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillators (ICDs) implanted when clinically indicated [27-29] (Table 4).

|

Clinical scenario |

NYHA Class |

Air Travel Recommendations |

|

Acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) |

Unfit for travel, 6-8 weeks recovery post-discharge, and reevaluation |

|

|

Chronic Stable Heart Failure |

||

|

Mild |

NYHA-II-II |

Fit to fly |

|

Moderate |

NYHA-III |

Consideration of in-flight oxygen and airport assistance |

|

Severe |

NYHA-IV |

Avoid unnecessary air travel Specialist consultation for fitness evaluation Strongly recommended to have onboard Inflight oxygen and airport assistance |

|

This table outlines guidance for patients with heart failure based on symptom severity and New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification. Acute decompensated states are contraindications, while stable patients may travel with appropriate precautions such as in-flight oxygen or medical clearance. (Abbreviations: ADHF: Acute Decompensated Heart Failure; NYHA: New York Heart Association) |

||

Table 4: Air Travel Recommendations for Patients with Heart Failure.

Left Ventricular Assist Devices (LVADs)

The use of Left Ventricular Assist Devices (LVADs) has increased as a bridging therapy [29]. Although the idea of LVADs might seem unsettling, patients who are clinically stable are generally considered safe for air travel. Notably, no significant issues have been reported with airport security screening devices or in-flight electronic systems [30-32] (Table 5).

|

Timing of Left ventricular assistance device (LVAD) implantation |

Travel recommendations |

|

Recently Implanted |

Defer nonessential travel for 8 weeks post-op |

|

Socialist consultation before travel |

|

|

Airport assistance/medical escort and in-flight oxygen |

|

|

3-6 months of implantation |

Travel when necessary. |

|

Consult a specialist before travel. |

|

|

Do not travel alone, and highly recommend using airport assistance services. |

|

|

General advice |

Bring your LVAD medical record for security clearance |

|

Check INR 24-48 hours before flight |

|

|

Carry on a fully charged extra LVAD battery |

|

|

Coordinate with LVAD-experienced centers at your destination to ensure optimal care. |

|

|

This table provides guidance for LVAD recipients planning air travel, with recommendations based on timing post-implantation and necessary precautions. Emphasis is placed on medical readiness, device logistics, and coordination with experienced care centers. (Abbreviations: LVAD: Left Ventricular Assist Device; INR: International Normalized Ratio) |

|

Table 5: Air Travel Recommendations for Patients with Left Ventricular Assist Devices (LVADs).

Cardiac Arrhythmias

Cardiac arrhythmia is broadly divided into tachyarrhythmias and bradyarrhythmias. Although in-flight hypoxia and increased sympathetic activation can increase the risk of cardiac arrhythmias, significant arrhythmias during air travel are rare [13]. Passengers with uncontrolled symptomatic cardiac arrhythmias should avoid traveling and seek specialist evaluation, whereas those with stable chronic arrhythmias are generally considered fit for air travel [29,33] (Table 6).

|

Clinical scenario |

Travel recommendations |

|

Tachyarrhythmias (Afib with RVR, SVT, AT) |

|

|

Symptomatic and uncontrolled |

Avoid unnecessary travel and consult EP. |

|

Paroxysmal AF |

Unrestricted for flight, carry medications |

|

Resuscitation of cardiac arrest due to VT/VF, if there is no ICD, no reversible cause identified, and EF<35 |

Unfit for flight |

|

Consult EP and strongly recommend implanting an ICD |

|

|

Bradyarrhythmia’s |

|

|

Symptomatic |

Unfit for travel, pacemaker implantation |

|

Severe bradyarrhythmia (HR<40) |

Avoid unnecessary travel and EP consult |

|

This table summarizes guidance for patients with tachyarrhythmias and bradyarrhythmias. Travel fitness depends on symptom control, presence of life-threatening rhythms, and the need for device therapy. Specialist electrophysiology (EP) consultation is advised in high-risk cases. (Abbreviations: AF: Atrial Fibrillation; RVR: Rapid Ventricular Response; SVT: Supraventricular Tachycardia; AT: Atrial Tachycardia; VT: Ventricular Tachycardia; VF: Ventricular Fibrillation; ICD: Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator; EF: Ejection Fraction; EP: Electrophysiologist) |

|

Table 6: Air Travel Recommendations for Patients with Cardiac Arrhythmias.

Cardiac Implantable Electronic Devices (CIED) and Pacemakers

It is estimated that over 300,000 new Cardiac Implantable Electronic Devices (CIEDs) are implanted annually in the U.S. [34]. Patients with Cardiac Implantable Electronic Devices (CIEDs) are classified into two groups: those with newly implanted devices and those with chronic implants. Travelers with recently implanted CIEDs may be cleared for air travel if they are stable, have no pneumothorax, controlled pain, and confirmed normal device function [35]. If a pneumothorax develops, air travel should be postponed for at least two weeks after its resolution [36]. For individuals with chronic CIEDs, air travel is not recommended if there is abnormal device function or a recent ICD shock, and they should consult an electrophysiologist and aviation medicine specialist before traveling [37]. Minimal interference with Cardiac Implantable Electronic Devices (CIEDs) has been reported from airport security systems and in-flight avionics, and these devices are generally well tolerated [38]. Left-sided electrophysiological procedures or ablation place patients at an increased risk of systemic embolization due to potential thrombus formation from catheters or endocardial lesions. Therefore, anticoagulation is strongly recommended to reduce this risk, and unnecessary travel should be postponed [14,35] (Table 7).

|

Category |

Travel Clearance Criteria |

Recommendations |

Notes |

|

Newly Implanted CIEDs |

-Stable device function - No pneumothorax - Controlled pain |

May travel after clinical stability is confirmed |

If pneumothorax occurs, defer travel for ≥2 weeks after resolution |

|

Chronic CIEDs |

- Normal device function - No recent ICD shock |

Avoid air travel if you have abnormal device function or a recent ICD shock. Seek clearance from the electrophysiologist and aviation medicine. |

Routine pre-travel evaluation advised. |

|

Security Systems & In- Flight Avionics |

Not contraindicated |

Minimal interference reported |

Modern airport scanners and aircraft systems rarely interfere with CIEDs |

|

Post-Electrophysiological Procedures |

After left-sided EP/ablation procedures, the risk of systemic embolism from thrombus |

Recommend anticoagulation and delay unnecessary travel |

Due to the risk of catheterinduced thrombus or endocardial lesions |

|

This table outlines recommendations for patients with newly implanted or chronic CIEDs, including pacemakers and Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillators (ICDs). Travel decisions should be based on device stability, absence of complications, and recent procedural history. Modern airport and in-flight electronics are generally safe but routine pre-travel clearance is advised. (Abbreviations: CIED: Cardiac Implantable Electronic Device; ICD: Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator; EP: Electrophysiology) |

|||

Table 7: Air Travel Considerations for Patients with Cardiac Implantable Electronic Devices (CIEDs).

Postcardiac Surgery and Cardiac Transplant

Stable cardiac surgery patients are usually cleared for travel 10 to 14 days after surgery, as long as their haemoglobin levels are checked beforehand. If complications such as pneumothorax or pneumomediastinum occur, travel should be delayed until full recovery and the resolution of air build-up. Currently, there are no clear guidelines regarding air travel after heart transplantation. However, a study suggests that patients can safely fly, but the study participants had at least three years post-transplantation before air travel [39]. Long-haul flights pose significant challenges for heart transplant recipients due to their immunosuppressed status, making it crucial to implement appropriate prophylactic measures to protect their well-being during travel [39].

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to the content of this manuscript. No financial, personal, or professional relationships influenced the preparation of this review.

Funding Statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The Department of Internal Medicine, Sanford School of Medicine, University of South Dakota,USA will sponsor publication charges.

Author Contributions

- Dawlat Khan, MD: Conceptualization, literature review, manuscript drafting, and critical revision.

- Dawood Shehzad: Literature search, drafting of ischemic heart disease section, and critical revisions.

- Haddaya Umar: Literature search, drafting of heart failure section, and critical revisions

- Bilal Jamshaid: Conducted literature search, drafted the arrhythmias section, and performed critical revisions.

- Fnu Abubakar: Literature search, drafted the LVAD section

- Zain Saeed Alzahrani: Literature search, drafted introduction, physiological effect on altitude section and heart transplant portion.

- Hammad Chaudhr: Literature search, drafting of arrhythmias and heart transplant and cardiac devices section, and critical revisions

- All authors: Approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

References

- Roth GA, Mensah GA, Johnson CO, Addolorato G, Ammirati E, et al. (2020) Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors, 1990-2019: Update from the GBD 2019 Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 76: 2982-3021.

- World Bank (2026) World Bank Open Data.

- Katoch T, Pinnamaneni S, Medatwal R, Anamika F, Aggarwal K, et al. (2024) Hearts in the sky: understanding the cardiovascular implications of air travel. Future Cardiol 20: 651-660.

- Bhatia N, El-Chami M (2018) Leadless pacemakers: a contemporary review. J Geriatr Cardiol 15: 249-253.

- Schuger CD, Ando K, Cantillon DJ, Lambiase PD, Mont L, et al. (2021) Assessment of primary prevention patients receiving an ICD - Systematic evaluation of ATP: APPRAISE ATP. Heart Rhythm O2 2: 405-411.

- Jorde UP, Saeed O, Koehl D, Morris AA, Wood KL, et al. (2024) The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Intermacs 2023 Annual Report: Focus on Magnetically Levitated Devices. Ann Thorac Surg 117: 33-44.

- UNOS (2023) 2022 organ transplants again set annual records.

- https://public-inspection.federalregister.gov/2023-12454. pdf?1686746716

- Cottrell JJ (1988) Altitude Exposures during Aircraft Flight: Flying Higher. CHEST 93: 81-84.

- Humphreys S, Deyermond R, Bali I, Stevenson M, Fee JPH (2005) The effect of high altitude commercial air travel on oxygen saturation. Anaesthesia 60: 458-460.

- Carvalho AM, Poirier V (2009) So you think you can fly?: determining if your emergency department patient is fit for air travel. Can Fam Physician 55: 992-995.

- Medical Guidelines for Airline Travel. Aerospace Medical Association.

- Possick SE, Barry M (2004) Evaluation and management of the cardiovascular patient embarking on air travel. Ann Intern Med 141: 148-154.

- Koh CH (2021) Commercial Air Travel for Passengers with Cardiovascular Disease: Recommendations for Common Conditions. Curr Probl Cardiol 46: 100768.

- Al-Janabi F, Mammen R, Karamasis G, Davies J, Keeble T (2018) In-flight angina pectoris; an unusual presentation. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 18: 61.

- Silber S (2019) ESC-Leitlinie 2019 zum chronischen Koronarsyndrom (CCS, vormals „stabile KHK“). Herz 44: 676-683.

- Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J, Berra K, Blankenship JC, et al. (2012) 2012 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS Guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/ American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the American College of Physicians, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation 126: e354-e471.

- Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, et al. (2018) 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 39: 119-177.

- DeHart RL (2003) Health issues of air travel. Annu Rev Public Health 24: 133-151.

- Wang W, Brady WJ, O’Connor RE, Sutherland S, Durand-Brochec MF, et al. (2012) Non-urgent commercial air travel after acute myocardial infarction: a review of the literature and commentary on the recommendations. Air Med J 31: 231-237.

- Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, Casey Jr DE, Ganiats TG, et al. (2014) 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients with Non-ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 64: e139-e228.

- Smith D, Toff W, Joy M, Dowdall N, Johnston R, et al. (2010) Fitness to fly for passengers with cardiovascular disease. Heart 96: ii1-16.

- Cox GR, Peterson J, Bouchel L, Delmas JJ (1996) Safety of commercial air travel following myocardial infarction. Aviat Space Environ Med 67: 976-982.

- Thomas MD, Hinds R, Walker C, Morgan F, Mason P, et al. (2006) Safety of aeromedical repatriation after myocardial infarction: a retrospective study. Heart 92: 1864-1865.

- Bozkurt B, Colvin M, Cook J, Cooper LT, Deswal A (2016) Current Diagnostic and Treatment Strategies for Specific Dilated Cardiomyopathies: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 134: e579-e646.

- Agostoni P, Cattadori G, Guazzi M, Bussotti M, Conca C, et al. (2000) Effects of simulated altitude-induced hypoxia on exercise capacity in patients with chronic heart failure. Am J Med 109: 450-455.

- Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JGF, et al. (2016) 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 37: 2129-2200.

- Cardiovascular disease | UK Civil Aviation Authority.

- Simpson C, Dorian P, Gupta A, Hamilton R, Hart S, et al. (2004) Assessment of the cardiac patient for fitness to drive: drive subgroup executive summary. Can J Cardiol 20: 1314-1320.

- Haddad M, Masters RG, Hendry PJ, Kawai A, Veinot JP, et al. (2004) Intercontinental LVAS Patient Transport. Ann Thorac Surg 78: 18181820.

- University of California San Francisco (2026) FAQ: Living with a Ventricular Assist Device (VAD).

- Matsuwaka R, Matsuda H, Kaneko M, Miyamoto Y, Masai T, et al. (1995) Overseas transport of a patient with an extracorporeal left ventricular assist device. Ann Thorac Surg 59: 522-523.

- Antuñano MJ, Baisden DL, Davis J, Hastings JD, Jennings R, et al. (2006) Guidance for Medical Screening of Commercial Aerospace Passengers. Federal Aviation Administration.

- Schuger CD, Ando K, Cantillon DJ, Lambiase PD, Mont L, et al. (2021) Assessment of primary prevention patients receiving an ICD – Systematic evaluation of ATP: APPRAISE ATP. Heart Rhythm O2 2: 405-411.

- Koh CH (2021) Commercial Air Travel for Passengers with Cardiovascular Disease: Stressors of Flight and Aeromedical Impact. Curr Probl Cardiol 46: 100746.

- Chauhan A, Grace AA, Newell SA, Stone DL, Shapiro LM, et al. (1994) Early complications after dual chamber versus single chamber pacemaker implantation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 17: 2012-2015.

- Naouri D, Lapostolle F, Rondet C, Ganansia O, Pateron D, et al. (2016) Prevention of Medical Events During Air Travel: A Narrative Review. Am J Med 129: 1000.e1-1000.e6.

- Yerra L, Reddy PC (2007) Effects of electromagnetic interference on implanted cardiac devices and their management. Cardiol Rev 15: 304-309.

- American Society of Transplantation (2026) Guide to Safe Travel after Transplant.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.