A Pilot Study of Mild TBI in College Athletes and Noninvasive Neuroimaging for Objective Indicators

by Dylan Bhandary1,2, Pushpa Sharma2, Dominic E Nathan3-5*

1University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA

2Department of Anesthesiology, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda,USA

3Military Traumatic Brain Injury Initiative, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda,USA

4Henry M Jackson Foundation, Bethesda,USA

5National Institutes of Health, Bethesda,USA

*Corresponding author: Dominic E Nathan, Department of Military Traumatic Brain Injury Initiative, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, USA

Received Date: November 17, 2025

Accepted Date: November 27, 2025

Published Date: November 30, 2025

Citation: Bhandary D, Sharma P, Nathan DE (2025) A Pilot Study of Mild TBI in College Athletes and Noninvasive Neuroimaging for Objective Indicators. J Neurol Exp Neural Sci 7: 167. https://doi.org/10.29011/2577-1442.100067

Abstract

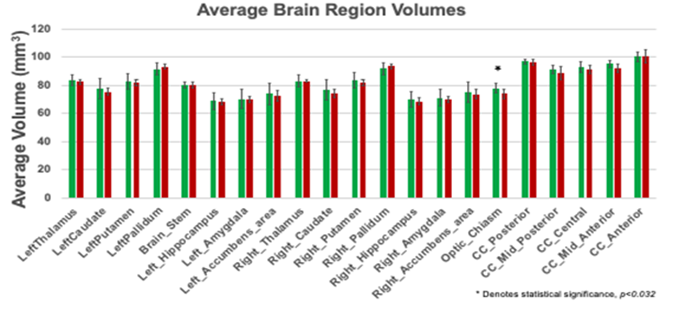

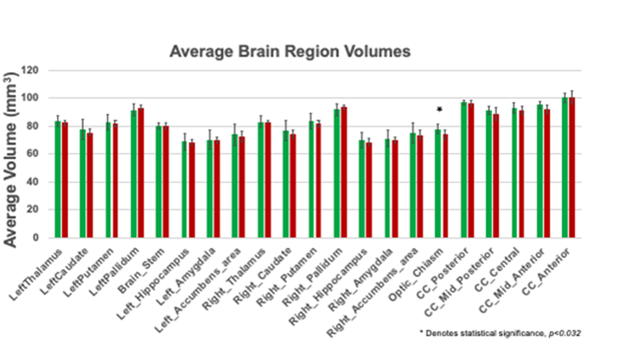

Background: Mild Traumatic Brain Injury (mTBI) or concussions are relatively common in college football athletes compared to other sports, often results in long lasting cognitive, emotional, and functional impairment with symptoms varying across individuals. Many patients recover within few weeks, however some experience chronic symptoms. At present objective indicators of recovery or symptom outcomes are unclear. The goal of this retrospective study was to examine MRI anatomical imaging of the brain to identify potential early risk factors at injury onset that could lead to the chronic neurological symptoms, (>6 months post injury). Methods: All subjects were college athletes (mean age 19.5+1.6 years) with a diagnosis of mTBI, scanned with a 3T MRI scanner at the time of injury, and were subjected to a battery of neurological assessments. We focused on the Vestibular Ocular Motor Screening (VOMS) measure for its simplicity of use; specifically, the VOMS does not require any equipment and individuals can be easily trained to administer this assessment. These considerations are important for military applications, in particular for austere environments. Results: We identified individuals with VOMS symptoms at the 6-month visit (N=6, mean age 19.5+1.6 years) and compared these results to age and gender matched control individuals (N=12, mean age 19.5+1.5 years) without VOMS symptoms. We analyzed the T1-weighted MRI images using the Free Surfer Software package. The results suggest a significant statistical difference in the optic chiasm between two groups (p<0.032). Conclusions: This is an important study with interesting finding as it provides a method to quickly and effectively determine if an individual will experience symptoms related to visual and vestibular disturbances.

Introduction

Mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) is the most common type of TBI, resulting in approximately 2.5 million emergency visits every year [14]. Most individuals recover between 2-4 weeks, however, many patients suffer from long lasting cognitive, emotional, and functional impairment [1]. Oculomotor dysfunction is one of the most common symptoms associated with 90% of TBI patients [3]. Oculomotor dysfunction manifests as difficulty with eye movements, and focusing, with some dominant examples such as (1) Accommodation: The ability of the eye to focus on objects at different distances, (2) Convergence: The coordinated movement of both eyes to maintain single vision when looking at objects at different distances (3) Smooth Pursuits: The ability to smoothly track a moving object with the eyes, (4) Saccades: The rapid, jerky eye movements used to shift gaze from one object to another, (5) Convergence Insufficiency: Difficulty with the eyes turning inward to focus on near objects and (6) Accommodative Dysfunction: Difficulty adjusting focus between near and far objects. Oculomotor and visual dysfunctions can significantly impact activities of daily living including reading, driving, and employment related activities [1]. Treatment often includes specialized vision therapy and rehabilitation, but not all medical care facilities are equipped to diagnose and provide this specific level of care. Current diagnosis of mTBI involves clinical assessment to include the patient’s medical history, and a series of baseline tests. However, there is heavy dependence on patient self-report of traumatic events and symptoms, and the prediction of recovery outcomes remains complicated. In addition, the overlap of symptoms and comorbidities such as post-traumatic stress, depression and sleep disturbances that often accompany mTBI presents an added layer of complication in treatment [13].

The use of neuroimaging tools such as Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) provides opportunities to noninvasively diagnose mTBI in vivo. However, symptomatic individuals with mTBI often have MRI scans that are inconclusive or without any significant findings [4,6,8].

Mild traumatic brain injury can create persisting brain injury that often goes unnoticed in magnetic resonance imaging tools. mTBI is hard to detect on an MRI because it presents as many different symptoms across multiple people; this means that some patients may have headaches which appear immediately, which others have vision problems that may develop later. Secondly, mTBI is hard to diagnose due to the lack of clear neuroimaging findings; this is a result of unpredictability of pathological changes from patient to patient as well as delay in post injury clinical evaluations. Damage inside the brain varies by person, so it is hard to relate to what is seen in brain scans with injury. Also, patients are not always assessed right after injury, and by the time they are evaluated, damage might now show up in the biomarkers, not showing its true findings. The objective of this pilot study is to explore neuroimaging correlates of mTBI ocular motor dysfunction [7].

Methods

Participants

This retrospective study included college athletes (mean age 19.5 ± 1.6 years) with clinically confirmed mTBI. All participants underwent MRI scans within days of injury and a battery of neurological assessments. From 241 initially screened, 22 had high-quality MRI data. Of these, 6 athletes exhibited persistent VOMS-related symptoms at 6 months and were compared with 12 age- and sex-matched asymptomatic controls.

Clinical Assessment

Vestibular/Ocular Motor Screening (VOMS) was created as a clinical screening tool for identifying symptoms and impairments post-concussion. While it is a reliable tool for assessing concussion symptoms, it can give false positives, as evidenced by 22% of cases. A positive result means delayed recovery, but symptoms can improve with specific treatments [5]. The VOMS proved to be the best assessment to use for this study because of its simplicity, as it does not need equipment, and is easy to train as well as administer. These factors appeal to be used in the military as well as the civilian population because of how quickly the test can be carried out, and how easy it is to examine subjects. The lack of equipment and simple nature of this assessment means thousands of assessments can be administered, which allows researchers to access a large sample size of the military and civilian population [11,12,15].

The VOMS assessment consists of smooth pursuits, saccades, convergence, and vestibular ocular reflex tests to assess executive functions which are affected by brain injury. Smooth pursuits involve following a target, and the saccades has a horizontal as well as vertical component which moves the eyes quickly between horizonal and vertical targets. The convergence test assesses a subject's ability to view a near target without double vision. Lastly, the vestibular ocular reflex test (VOR) examines a subject's ability to stabilize vision as the head moves by testing their ability to see horizontal and vertical targets [1].

MRI Acquisition and Analysis

MRI scans were acquired using a 3T Siemens scanner. High-resolution T1-weighted images were processed with FreeSurfer software to segment cortical and subcortical structures.⁹ Regions of interest included the corpus callosum and optic chiasm. Preprocessing included tessellation, smoothing, and hemispheric registration.

Volumetric comparisons were made between chronic-symptom and control groups using independent-sample t-tests. Significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Our study aimed to assess the VOMS at 6 months in individuals with chronic symptoms and examine MRI data to determine if there are any neural correlates of chronic mTBI related impairment. A total of 241 subjects were used in the initial analysis. However, we focused on 6 individuals with chronic symptoms at 6 months out of 22 subjects who had good MRI data, and we selected 13 age and gender matched subjects with good MRI data (Table 1). Our results from the VOMS assessment (Table 2) showed 6 subjects that reported symptoms, and they all reported headaches as well as fogginess [16,17].

|

Group/ Gender |

Count |

Age |

|

Control Female |

5 |

19.6 |

|

Control Male |

8 |

19.5 |

|

Injured Female |

3 |

19.3 |

|

Injured Male |

3 |

19.7 |

Table 1: Number of subjects endorsing symptoms (total 6)

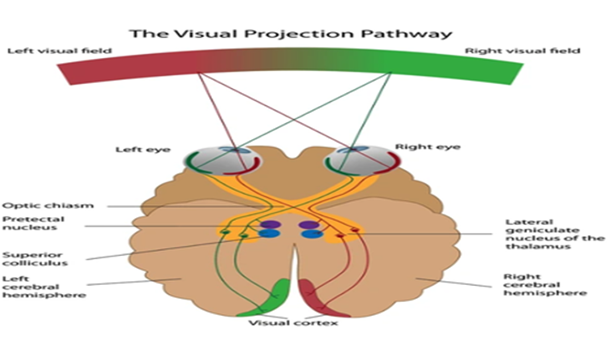

The MRI data of the control as well as injured groups for both male and females were acquired with a 3T MRI Siemens scanner. Brain regions were anatomically segmented, tessellated, surface smoothed, and spherically inflated for hemispherical registration. We focused on the subcortical regions with an emphasis on brain structures like the corpus callosum. Our results (Table 3) found a distinct difference between groups in the optic chiasm(p<0.032). The optic chiasm is the location where the optical nerves cross, carrying signals from the eye to the visual cortex (Table 4). It serves as a crossroads where almost half of the nerve fibers from each eye cross to the opposite side of the brain. As a result, visual information from the left visual field of both eyes is processed by the right cerebral hemisphere while visual information from the right visual field of both eyes is processed by the left cerebral hemisphere. If damaged, the crossing nerve fibers of each eye are affected, causing visual loss in the visual fields of both eyes [2] Damage to this region corresponds to impaired vision and visual disturbances and could explain the symptoms captured by the VOMS. Other regions such as the corpus collosum had trending lower average volumes in chronically injured subjects but did not reach statistical significance.

Table 2: Average brain region volume.

Table 3: Average brain volume for both control and injured groups.

Table 4: Function of the Optic Chiasm.

Results

From our study, we found that subjects with chronic symptoms had lower subcortical volumes, and this could be a result of injury to certain pathways in the brain. The impact concussion has on the optic chiasm indicates a common injury source in college athletes. Specifically, the motor impairments college athletes face is a result of damage to the optic chiasm. This study aims to understand how mild traumatic brain injury affects subcortical brain regions as well as executive and motor functions in college athletes. Our results can be used to develop blood-based biomarkers as well as imaging for concussion. These two tools will help to aid in detecting brain abnormalities in the earliest stages of injury, which means that it can be treated more effectively before symptoms worsen for patients. As a result, college athletes will be able to recover faster from concussions without the risk of persisting symptoms [13].

Discussion

This pilot study aimed to investigate the potential neuroimaging correlates of mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) in college athletes, with a particular focus on visual and vestibular disturbances as assessed by the Vestibular Ocular Motor Screening (VOMS). This study identifies structural changes in the optic chiasm as a potential correlate of persistent post-concussion symptoms in college athletes. These findings suggest that MRI-based volumetric assessment of visual pathways may provide objective biomarkers for chronic mTBI.

Additionally, the study researched the long-term effects of mTBI, meaning persisting symptoms were accounted for, something seldom studied. The call for use of biomarkers in the diagnosis stage of a concussion will also allow future studies to examine the effectiveness of a possible solution to brain injury. Lastly, this study identified a specific brain region (optic chiasm) affected by concussion, so diagnosis and treatment can be tailored to this region and target these pathways whenever a patient suffers from a concussion [10].

Despite the small sample size, our results provide valuable insights into the underlying neural mechanisms of mTBI, particularly the optic chiasm, a brain region central to visual processing. The study also highlights the potential for non-invasive neuroimaging tools, such as MRI, to help identify early biomarkers of chronic concussion symptoms, ultimately contributing to more accurate and efficient concussion management.

Key Findings

One of the most notable findings of this study is the identification of a statistically significant difference in the optic chiasm between athletes with chronic symptoms (6 months post-injury) and those without. The optic chiasm is a critical structure for visual processing, where the optic nerves cross over to the contralateral visual cortex. Damage to this area could lead to impaired visual processing and contribute to visual disturbances such as those identified in the VOMS, including issues with smooth pursuits, saccades, convergence, and the vestibular ocular reflex.

The finding of decreased subcortical volumes in chronic mTBI subjects, although not statistically significant in regions like the corpus callosum, underscores the potential for broader damage to the brain’s communication pathways. It suggests that the impact of mTBI could lead to subtle but lasting changes in brain structures, which may not be easily detectable with conventional clinical tests. This is especially relevant in athletes, who may experience repeated head impacts, and in military personnel operating in austere environments where immediate access to specialized care is limited.

In addition to visual disturbances, the VOMS identified symptoms such as headaches and fogginess, which are common in mTBI patients [9]. These symptoms align with the results of the MRI analysis, suggesting that the optic chiasm and other subcortical areas might play a pivotal role in the persistence of such post-injury symptoms.

Implications for Diagnosis and Treatment

The results of this study have important implications for both clinical diagnosis and the development of treatment strategies for mTBI. Currently, the diagnosis of mTBI is largely dependent on patient-reported symptoms and a series of clinical assessments, such as neurocognitive tests and balance assessments [5]. However, the absence of clear biomarkers in neuroimaging tools complicates diagnosis, particularly in cases where symptoms are subtle or delayed. Our finding of significant differences in the optic chiasm offers a potential neuroimaging marker that could help clinicians identify individuals at risk for chronic symptoms long before the emergence of more obvious neurocognitive deficits. If replicated in larger cohorts, MRI scans could become a routine part of mTBI diagnosis, providing clinicians with objective indicators to guide treatment decisions.

Moreover, understanding the role of the optic chiasm in post-concussion syndrome could lead to more targeted therapies. For example, treatment strategies aimed at restoring or compensating for visual deficits might become a core component of concussion rehabilitation. Currently, vision therapy is used to address oculomotor dysfunction, but its effectiveness could be further enhanced if clinicians have more precise knowledge of which brain regions are involved.

The findings also suggest that chronic symptoms, such as headaches and visual disturbances, might be mitigated if brain damage is identified early through neuroimaging. Given that many athletes and military personnel are at increased risk for repeated concussions, the ability to monitor brain changes over time could be vital for long-term health and performance.

Limitations and Future Directions

While this study provides valuable insights, it is not without limitations. The small sample size (N=6 with chronic symptoms) limits the generalizability of the results, and further research with a larger cohort is needed to confirm these findings. Additionally, the study's cross-sectional design cannot establish causality between mTBI and brain structural changes; longitudinal studies would be more effective in tracking the progression of injury over time. The fact that the study focused only on individuals who were evaluated 6 months post-injury introduces the possibility of selection bias, as those with less severe or transient symptoms may not have been included in the study.

Another limitation is the reliance on a single neuroimaging modality (MRI) and the exclusion of other advanced imaging techniques such as diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), which could provide more detailed insights into white matter integrity and connectivity. Additionally, the study did not include other potential biomarkers, such as blood-based markers of neuroinflammation, which are increasingly being explored for their role in diagnosing and predicting outcomes in mTBI [13]. Future research should also consider expanding the time frame for follow-up evaluations, exploring additional imaging techniques, and incorporating diverse patient populations, including individuals with multiple concussions, to investigate cumulative effects. It would also be worthwhile to investigate other brain regions potentially impacted by mTBI, such as the thalamus and basal ganglia, which are involved in motor control and sensory processing.

Potential Military and Military-Related Applications

In military contexts, where individuals may experience head injuries in combat or training environments, the ability to rapidly and noninvasively assess the brain for signs of mTBI could be life-saving. The simplicity and non-invasiveness of the VOMS assessment make it an ideal tool for field settings, while MRI scans, although not currently feasible for all military units, could be deployed in more advanced medical facilities or as part of a broader concussion management protocol. The findings from this study emphasize the importance of developing field-friendly neuroimaging tools and protocols to monitor the health of service members, as well as the utility of a neuroimaging biomarker to identify those at risk for developing chronic symptoms.

Conclusion

This pilot study provides evidence that chronic symptoms in college athletes following mild traumatic brain injury may be linked to structural changes in the optic chiasm and other subcortical brain regions. These findings suggest that early neuroimaging and symptom assessment using tools like the VOMS can aid in predicting long-term outcomes and identifying at-risk individuals. Although further research with larger cohorts is needed, this study contributes to the growing body of evidence supporting the need for objective, non-invasive biomarkers for mTBI. These biomarkers have the potential to revolutionize concussion diagnosis, management, and treatment, ultimately leading to faster recovery times and improved long-term outcomes for affected individuals.

Disclaimer: The opinions and assertions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Uniformed Services University or the Department of Defense.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- Mucha A, Collins MW, Elbin RJ, Furman JM, Troutman-Enseki C, et al. (2014) A Brief Vestibular/Ocular Motor Screening (VOMS) assessment to evaluate concussions: preliminary findings. Am J Sports Med 42(10): 2479-2486.

- Ali Nadeem (2025) Understanding Optic Chiasm Disorders: When Both Eyes Are Affected Differently. Optic Neurology.

- Almutairi NM (2025) Visual Dysfunctions in Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: A Focus on Accommodative System Impairments. Life 15(5): 744.

- Arciniegas DB, Anderson CA, Topkoff J, McAllister TW (2005) Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: A Neuropsychiatric Approach to Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 1(4): 311-327.

- Broglio SP, Harezlak J, Katz B, Zhao S, McAllister T, et al. (2019) Acute sport concussion assessment optimization: a prospective assessment from the CARE consortium. Sports Medicine 49(12):1977-1987.

- Hoppes CW, Garcia de la Huerta T, Faull S, Weightman M, Stojak M, et al. (2025) Utility of the Vestibular/Ocular Motor Screening in Military Medicine: A Systematic Review. Military Medicine 190(5-6): e969-e977.

- Kim SY, Yeh PH, Ollinger JM, Morris HD, Hood MN, et al. (2023) Military-related mild traumatic brain injury: clinical characteristics, advanced neuroimaging, and molecular mechanisms. Transl Psychiatry 13(1): 289.

- McAllister Thomas W (2016) Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Focus (American Psychiatric Publishing) 14(4): 410-421.

- Mucha A, Collins MW, Elbin RJ, Furman JM, Troutman-Enseki C, DeWolf, et al. (2014) A brief vestibular/ocular motor screening (VOMS) assessment to evaluate concussions: preliminary findings. The American journal of sports medicine 42(10): 2479-2486.

- Nathan DE, Bellgowan JF, Oakes TR, French LM, Nadar SR, et al. (2016) Assessing quantitative changes in intrinsic thalamic networks in blast and nonblast mild traumatic brain injury: implications for mechanisms of injury. Brain connectivity 6(5): 389-402.

- Navale V, Ji M, Vovk O, Misquitta L, Gebremichael T, et al. (2019) Development of an informatics system for accelerating biomedical research. F1000Research 8: 1430.

- Fischl B (2012) FreeSurfer Neuroimage 62(2): 774-781.

- Pozzato I, Meares S, Kifley A, Craig A, Gillett M, et al. (2020) Challenges in the Acute Identification of Mild Traumatic Brain Injuries: Results from an Emergency Department Surveillance Study. BMJ Open 10(2): e034494.

- Silver JM, McAllister TW, Arciniegas DB (2018). Textbook of traumatic brain injury. American Psychiatric Pub, USA.

- Silverberg ND, Duhaime A, Iaccarino MA (2020) Mild Traumatic Brain Injury in 2019-2020. JAMA 323(2): 177-178.

- Silverberg, Noah D, et al. (2019) JAMA- the Latest Medical Research, Reviews, and Guidelines.” Jama, Jama Network.

- Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, USA

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.