A Misdiagnosed Case of Uterine Didelphys with Obstructed Hemivagina with Ipsilateral Renal Agenesis: A Case Report

by Yashika Shivanna1, Sushma HP1, Al Ameen Asharaf2*

1Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Kangaroo Care, Bangalore, India

2Department of Surgery, SHO at Glenfield hospital, Leceister, UK

*Corresponding author: Al Ameen Asharaf, Department of Surgery, SHO at Glenfield hospital, Leceister, UK.

Received Date: 2 December 2024

Accepted Date: 7 December 2024

Published Date: 10 December 2024

Citation: Yashika S, Sushma HP, Asharaf AA (2024) A Misdiagnosed Case of Uterine Didelphys with Obstructed Hemivagina with Ipsilateral Renal Agenesis: A Case Report. Gynecol Obstet Open Acc 8: 222. https://doi.org/10.29011/2577-2236.100222

Abstract

The association of uterus didelphys with obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal agenesis is a syndrome known as Ohvira syndrome. The initial diagnosis in most cases is incorrect because of it’s low incidence and little clinical suspicion. It is usually diagnosed after menarche with the presence of dysmenorrhea, pelvic pain and a palpable abdominal mass secondary to hematocolpos. The diagnosis can only be made if the syndrome is suspected. The ultrasound and MRI are the diagnostic techniques.

Surgical resection of the obstructed vaginal septum is the definitive treatment and prevents possible complications. We present the case of a 18 year-old girl who presented with chronic pelvic pain followed by heavy yellowish white vaginal discharge. She was suffering from a chronic pelvic pain since a year which was misdiagnosed by a local doctor and was given a symptomatic treatment.

Introduction

OHVIRA syndrome (Obstructed Hemivagina and Ipsilateral Renal Anomaly), also known as Herlyn-Werner-Wunderlinch (HWW) syndrome, is a rare congenital Müllerian malformation characterized by the triad of uterine didelphys, obstructed hemivagina, and ipsilateral renal agenesis[1]. In 1979, the eponymous Herlyn-Werner-Wunderlinch was introduced to describe this syndrome, based on a report of four cases with congenital anomalies of the female urogenital tract [2]. In 2007, the term OHVIRA appeared in the English literature to describe cases of patients with obstructed hemivagina associated with an ipsilateral renal anomaly [3]. Anomalies in the development of the Müllerian ducts exhibit variable morphological expressions, depending on the time of embryological development during which the anomaly occurs. Approximately 40% of cases are associated with renal malformations due to the morphogenic relationship

between the Müllerian ducts and the mesonephric ducts during the ninth week of gestation [4]. OHVIRA syndrome accounts for 2-3% of all Müllerian anomalies [5]. The initial diagnosis is often incorrect due to its rarity, low incidence, and limited clinical suspicion. However, its association with endometriosis, pelvic infections, infertility, and obstetric complications highlights the need for accurate diagnosis [6]. Here, we describe the case of an 18-year-old patient who suffered from chronic debilitating pelvic pain for more than a year due to a lack of awareness about the disease and suspicion by the local clinician.

Case Report

An 18-year-old girl visited the emergency Obstetrics and Gynaecology department with complaints of chronic lower abdominal pain. Her vitals were stable. She had undergone investigations at a previous hospital which included, multiple urine routine examinations, abdominal scans, and CT scans. However, these investigations were not handed over to the patient party. The discharge summary suggested a bicornuate uterus with right renal agenesis. Her all records were evaluated, and endometriosis was suspected. She was started on Dienogest 2mg along with analgesics. However, she returned to the hospital after 15 days with complaints of debilitating pelvic pain for the past three days, associated with an excessive amount of vaginal discharge. She was admitted for further evaluation.

Past history

Birth and early childhood: She was born weighing 2.8 kg after a vaginal delivery without any perinatal complications. At the age of one year, she was diagnosed with left lower limb swelling and identified as having a lymphovascular malformation at St. John’s Hospital, Bangalore. She was further evaluated, and an above-knee amputation of the left lower limb was performed due to suspicion of Infantile sarcoma. Histopathological examination of the specimen conducted at Tata Memorial Hospital suggested 1) Infantile sarcoma and 2) Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour. She was fitted with an artificial limb at the age of 1.5 years.

At the age of 13, she developed cyclical abdominal pain and was admitted to St. John’s Hospital, where she was diagnosed with a bicornuate uterus with hematometra. She underwent cervical dilatation, and an intracervical Foley’s catheter was placed for three days. Following this, she was discharged and remained symptom-free until the previous year.

One year ago, she began experiencing recurrent lower abdominal pain leading her to consult a gynaecologist in her local area. She was treated for a urinary tract infection (UTI) and was prescribed parenteral analgesics and antispasmodics. She also received several courses of antibiotics.

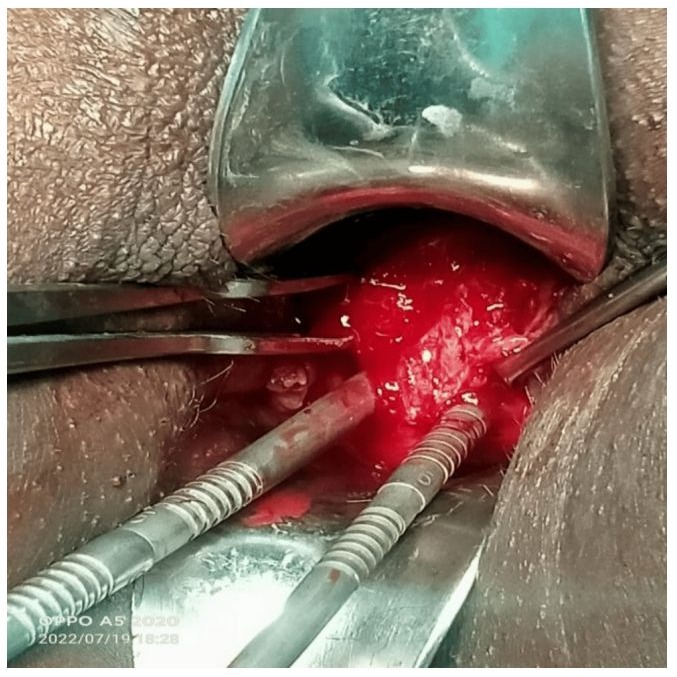

On admission, the patient was hemodynamically stable. A transvaginal scan revealed probe tenderness and identified a mixed echogenic mass measuring 5x7.2 cm, with an elongated appearance in contact with two uterine cavities.

Figure 1: High resolution transvaginal ultrasound image showing a mixed ecorefringence mass which could correspond with and endometrioma vs. hematometrocolpos

She was scheduled for surgery on the same day in the evening. Examination under general anesthesia revealed a mass on the right wall of the vagina, measuring approximately 5 x 5 cm, cystic in consistency. A cervix was seen on the left side of the mass. In light of these findings, a diagnostic hysteroscopy was performed. Initially, the hysteroscopy findings were inconclusive, as they showed a vaginal wall partially bulging due to a mass in the right lateral wall, while a normal cervix was noted lateralized to the left side of the pelvis.

An incision was made on the mass over the right vaginal wall, yielding a discharge of approximately 50ml of pus, which was sent for cytological analysis. Further exploration revealed a vaginal septum that had obscured another cervix. The septum was excised, and dilation of the cervix was performed using dilators. An intra-cervical foly catheter was placed, and the hysteroscopy was repeated.

In conclusion, based on the examination and hysteroscopic findings, the clinical diagnosis was uterus didelphys associated with piccolos due to a right obstructed hemivagina. This obstruction had, by continuity, retrogradely dilatated both hemi-uteri.

Figure 2: Intraoperative finding showing double cervix after excision of vaginal septum

Postoperative

Cervical catheter was removed after three days, and the patient was discharged. She had no postoperative complications. Her menstrual cycle normalized after 10 days, and she experienced relief from the pain.

Discussion

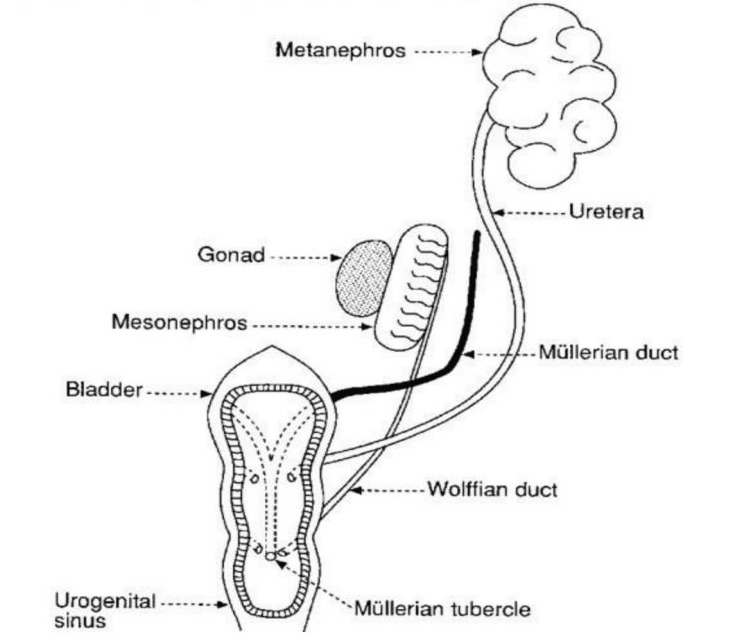

Both male and female embryos initially have two pairs of genital ducts: the mesonephric (or Wolffian) ducts and the paramesonephric (or Müllerian) ducts. While the mesonephric ducts derive directly from the mesonephros (primitive kidney), the paramesonephric ducts are formed from a longitudinal invagination of the epithelium of the coelomic epithelium.

The Müllerian ducts are located outside the ipsilateral Wolffian ducts, crossing them ventrally in their caudal portion to fuse with each other in the midline, reaching the urogenital sinus (Figure 3). Shortly after, the ends of the paramesonephric ducts fuse at the urogenital sinus. Two outflows, called sinovaginal bulbs, detach from the pelvic portion of the sinus and give rise to the lower two-thirds of the vagina. The upper third of the vagina derives from the uterine duct of paramesonephric origin.

Figure 3: Illustration of the link between the urogenital organs during development.

The Wolffian ducts, in addition to giving rise to the kidneys, facilitate the proper fusion of the Müllerian ducts. In OHVIRA syndrome, it is considered that there is an alteration in the conformation of both paramesonephric and mesonephric ducts, with the Wolffian duct being absent on one side (in 65% of cases the involvement occurs in the right side [1, 4]. On the side where the Wolffian ducts are absent, the Müllerian duct is displaced and cannot fuse with the contralateral, resulting in a didelphic uterus. The contralateral Müllerian duct gives rise to a normal hemivagina, while the dislocated one forms a blind cul-de-sac as a blind or obstructed hemivagina. For its part, the vaginal introitus is not affected due to its origin in the urogenital sinus. Renal agenesis is the consequence of the absence of the ipsilateral Wolffian duct due to premature degeneration of the ureteral bud, which is responsible for inducing the development of excretory units.

OHVIRA syndrome is an extremely rare condition, reason why in most cases the initial diagnosis is incorrect. It would be advisable to look for an associated Mullerian anomaly in cases of prenatal or neonatal diagnosis of renal agenesis or multicystic dysplasia, but even so, most patients remain asymptomatic until menarche and are usually discovered shortly after it when they debut with dysmenorrhea, pelvic pain, mass palpable or visible on ultrasound due to associated hematocolpos and / or hematometra due to retained bleeding, frequently confused with endometrioma or with a complex ovarian cyst [7]. The possible complications associated with this syndrome are a consequence of retrograde menstruation, such as endometriosis, pelvic adhesions, infectious collections and pelvic inflammatory diseases. The diagnosis can be made only if the syndrome is suspected [2]. The technique of choice for diagnosis is ultrasound, but the magnetic resonance imaging can also contribute with the diagnosis and classification of the malformation [3]. Laparoscopy can be of great help for diagnosis in selected cases, as the case of our patient.

Adequate recognition of this syndrome and early surgical resection of the vaginal septum determinates the rapid clinical improvement, prevention of complications, and maintenance of fertility[1]The number of pregnancies in patients with OHVIRA syndrome has been reported as successful, with a ratio of pregnancies up to 87% of cases, 23% of abortion, 15% of preterm deliveries and 62% of full-term pregnancy without complications [1].

Conclusion

OHVIRA is a rare syndrome of Mullerian and Wolffian duct abnormalities that require the clinical suspicion of the clinician to be diagnosed. Most cases are diagnosed after menarche, with the onset of the symptoms. Due to its rarity and the lack of awareness, it is often misdiagnosed or diagnosis is delayed which leads to the appearance of gynecological complications in young women. Thus, with the finding of renal agenesia or multicystic dysplasia, other genital malformations should be suspected and ruled out Ultrasound and MRI play a big role in the diagnosis and surgical decision. Laparoscopic surgery can also be useful in selected cases. The final treatment requires an excision of the obstructing vaginal septum.

References

- Begona Navarro Diaz, Natalia Siverio Colomina, Elena Moreno Perez (2020) Ohvira Syndrome: A case report. Journal of Gynaecology and Pediatric Care 3 (2).

- Paz-Montañez, John Jamer; Gaitán-Guzmán, Luisa Fernanda; Acosta-Aragón, et al. (2020). Síndrome de OHVIRA, a propósito de un caso. Univ Salud. 22: 288-291.

- Santos X, Dietrich J (2016). Obstructed Hemivagina with Ipsilateral Renal Anomaly. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 29: 7-10.

- Mandava A, Prabhakar R, Smitha S (2012). OHVIRA Syndrome (obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal anomaly) with Uterus Didelphys, an Unusual Presentation. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 25: e23-5.

- Villagómez C, Cordero L, Uscanga MC, Espínola C (2013). Síndrome OHVIRA (Útero didelfo con hemovagina obstruida y agenesia renal ipsilateral). Un caso inusual de infertilidad. Rev Sanid Milit Mex 67(6):297-300.

- Sadler TW (1987) editor. Langman. Embriología médica. Buenos Aires: Editorial Médica Panamericana SA.

- Boria F, Lucas J, Álvarez C, Poza J (2019) Síndrome de HerlynWernwe-Wünderlich y diagnóstico tardío; a propósito de un caso. Rev Peru Ginecol Obstet. 65: 337-340.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.