A Case Report: A Diagnosis of Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia Made in a Pediatric Patient in the Emergency Department Identified from Delay in Post Intubation Sedation

by Kevin Bosnoyan, MD, Rodney Fullmer, DO, MBS, FACEP, FACOEP*

Department of Emergency Medicine, Swedish Hospital, Chicago, IL, USA.

*Corresponding author: Kevin Bosnoyan, Department of Emergency Medicine, Swedish Hospital, Chicago, IL, USA.

Received Date: 22 January, 2026

Accepted Date: 28 January, 2026

Published Date: 31 January, 2026

Citation: Bosnoyan K (2026) A Case Report: A Diagnosis of Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia Made in a Pediatric Patient in the Emergency Department Identified from Delay in Post Intubation Sedation. Emerg Med Inves 11: 144. https://doi.org/10.29011/2475-5605.100144

Abstract

Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT) is a rare inherited arrhythmia syndrome that can present with life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias in the absence of structural heart disease. Recognition in the emergency setting is challenging, and missed diagnosis is often fatal. A 16-year-old male presented to the Emergency Department after an out-ofhospital cardiac arrest with ventricular fibrillation and achieved return of spontaneous circulation following defibrillation and resuscitation. The event occurred after prolonged fasting and physical exertion. Initial evaluation revealed no structural cardiac abnormalities. Following intubation, delayed post-intubation sedation led to agitation which coincided with the development of frequent premature ventricular contractions and episodes of non-sustained ventricular tachycardia on continuous cardiac monitoring. Escalation of sedation resulted in improvement of ventricular ectopy. Consultation with pediatric electrophysiology raised concern for CPVT, prompting initiation of beta-blocker therapy. After stabilization, the patient was safely transferred to a tertiary pediatric center, where genetic testing identified a pathogenic RYR2 variant, confirming a diagnosis of CPVT. This case highlights the importance of continuous cardiac monitoring and vigilance for evolving arrhythmias in pediatric patients following resuscitation. Delayed or inadequate sedation may exacerbate catecholamine-mediated ventricular arrhythmias and unmask underlying channelopathies. Early recognition, optimization of sedation, prompt beta-blockade, and multidisciplinary collaboration were critical in preventing further clinical deterioration and facilitating safe transfer of care.

Keywords: Case Report; Syncope; Arrythmia; Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia; Pediatric Cardiac Arrest.

Introduction

Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia (CPVT) is an inherited cardiac channelopathy without any structural heart disease that causes an arrythmia syndrome. It is a genetic disease that is characterized by a normal EKG with ventricular events triggered by exercise and catecholaminergic stress inducing premature ventricular contractions (PVC), and polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (PVT) [1]. The disease is caused by mutations in the cardiac ryanodine receptor gene (RYR2) or mutations in the cardiac calsequestrin gene (CASQ2) [2]. CPVT is seen in pediatric and adolescent population and presents as episodic syncope occurring during exercise or increased stressors [3]. The cause of the syncope occurs due to onset of ventricular tachycardia that could self-terminate or may transform into ventricular fibrillation and cause sudden death. The mean age is between seven and twelve years old and if undiagnosed and untreated, CPVT is highly lethal [2]. Approximately 30% of individuals experience at least one cardiac arrest and up to 80% have one or more syncopal episodes. Unfortunately, first presentation can also be sudden cardiac death [1-3].

Case Report

A 16-year-old male presented to the Emergency Department (ED) by Emergency Medical Services (EMS) after being found unresponsive. Per EMS records, upon their arrival, patient was found unresponsive, apneic, and pulseless with CPR in progress by his father. Patient was found to be in ventricular fibrillation was defibrillated once, then went into pulseless electrical activity, at which point CPR was continued. He received one dose of epinephrine and achieved return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), he was then transported to our ED.

On arrival, Father stated that his son had been fasting all day in observance with the Holy month of Ramadan and was playing tag with his friends when he observed him collapsing to the ground.

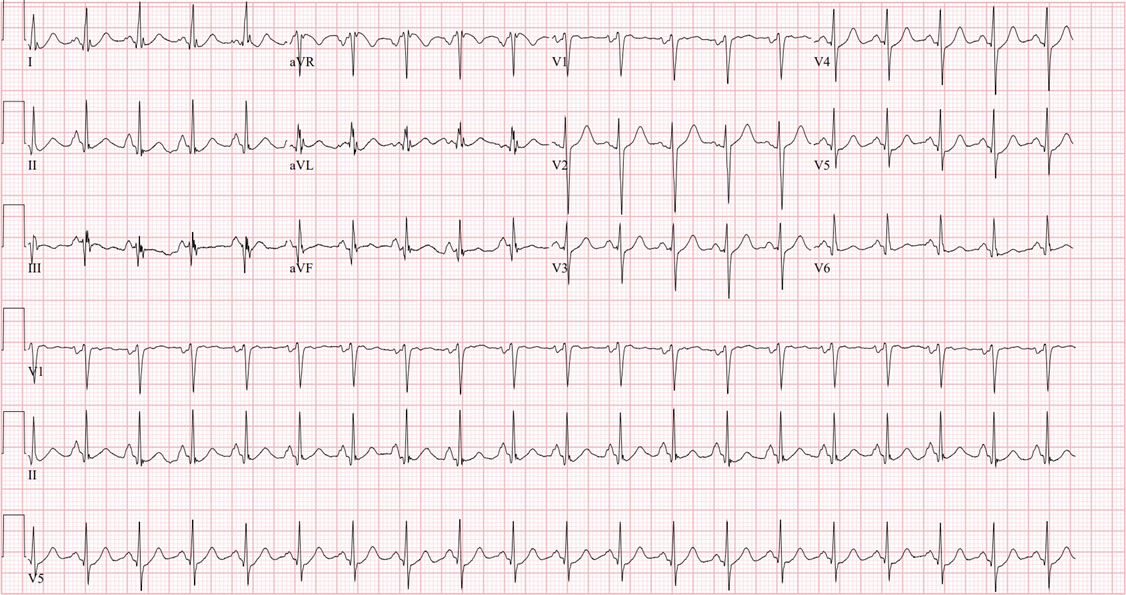

In the Emergency Department, patients’ vital signs were heart rate of 96 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 19, blood pressure 144/85, oxygen saturation 100% through Laryngeal Mask Airway (LMA). Patient was immediately intubated via video-glidescope using a seven and a half cuffed endotracheal tube. Sedation and paralysis were obtained with etomidate and rocuronium respectively. Initial EKG revealed sinus tachycardia at a heart rate of 122 with Q waves in lead III as well as lead II and aVF, there were no significant ST elevation noted, T wave inversions were seen in lead III.

The patient’s father noted no past medical, surgical, or social history. He had no allergies or medications he was taking regularly. Father did state that the patient had a syncopal episode a couple of years ago while playing basketball but regained consciousness immediately. A cardiac work up, including an echocardiogram revealed no abnormality.

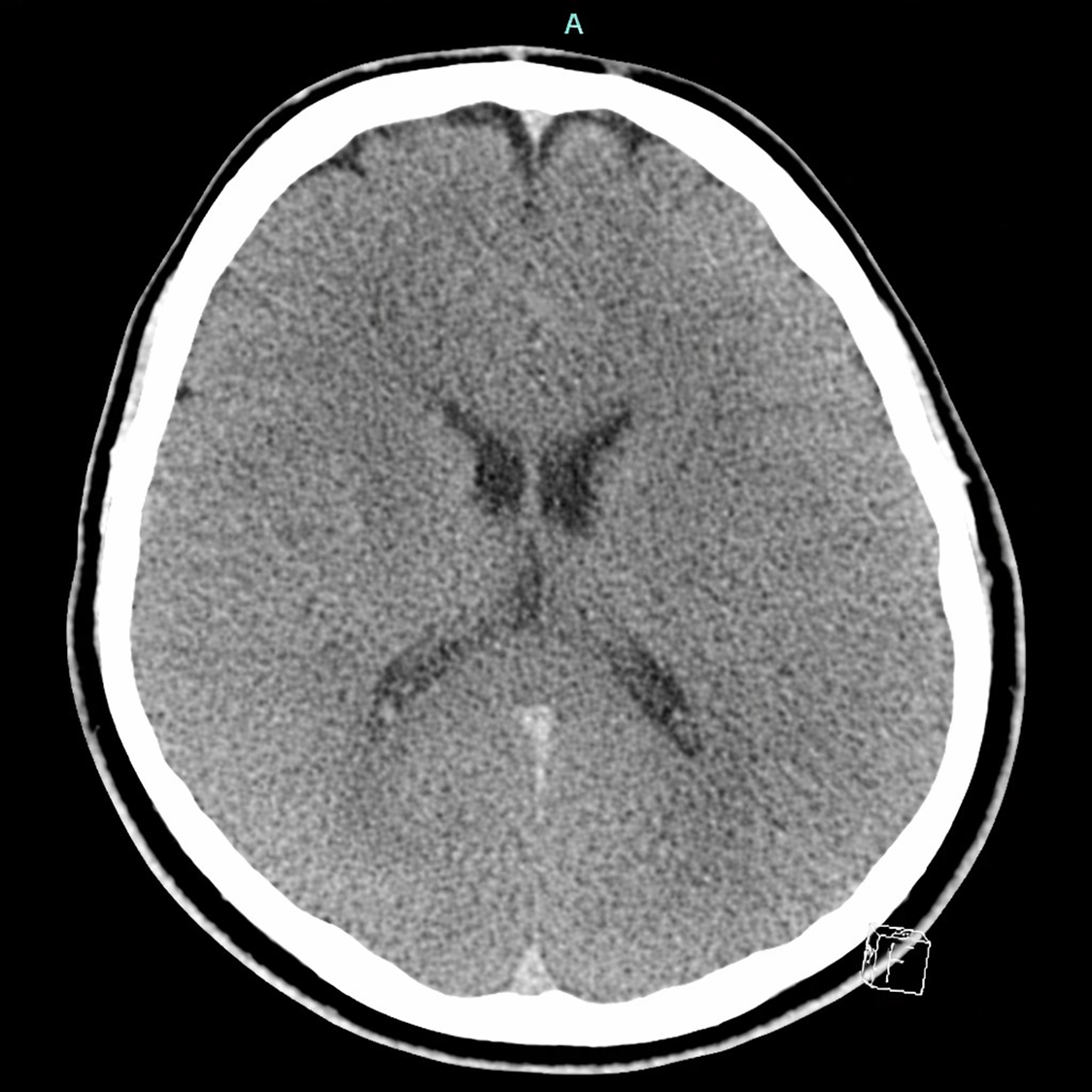

nitial ED work up ordered included Complete Blood Count (CBC), Complete Metabolic Panel (CMP), EKG, CT head without contrast, Lactic Acid, Magnesium, and Phosphorus levels. Meanwhile, a pediatric center was contacted to transfer to a pediatric intensive care unit.

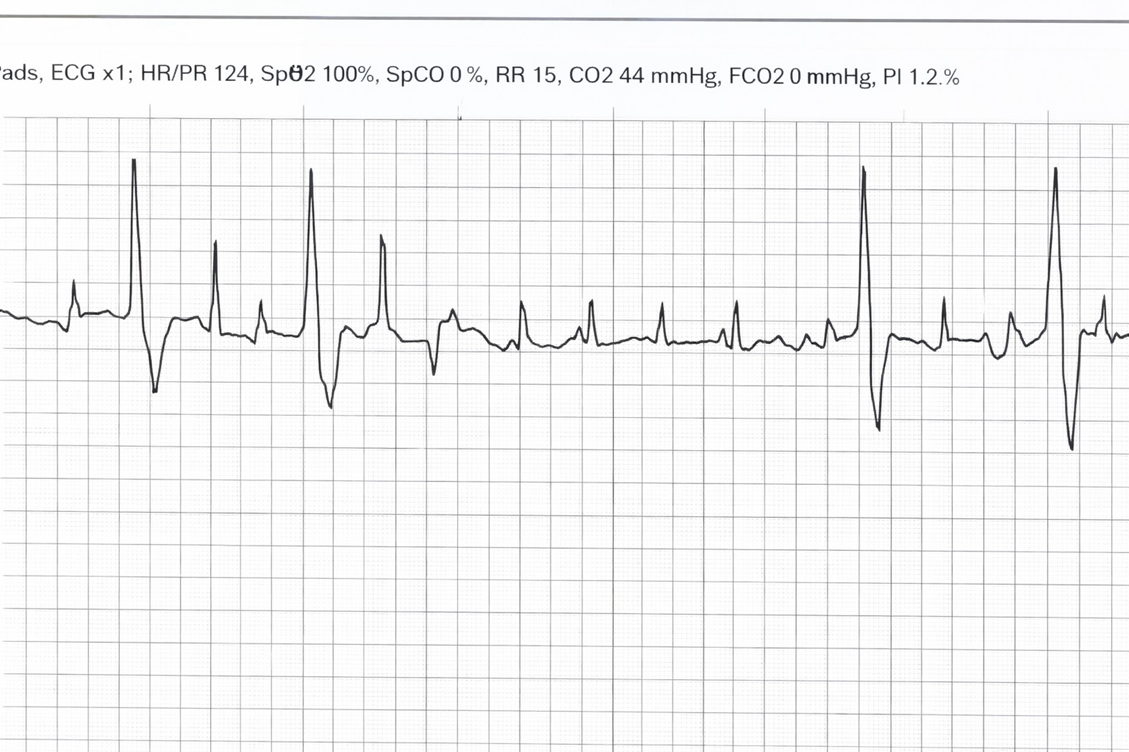

Upon re-assessment, the pediatric transfer team arrived at bedside and while transferring the patient, the cardiac monitor started to show cardiac rhythm changes. Ectopic beats became more frequent, the patient began to illicit a gag reflex, and initiating spontaneous breaths. Due to a pharmacy delay in sedation medication the patient became more agitated. As the agitation became more frequent, his cardiac rhythm showed more ectopy and episodes of new non-sustained ventricular tachycardia. At that moment, the patient was deemed unsafe for transport, five milligram (mg) Midazolam IV push doses were given that resulted with decrease in ectopy beats and tachycardia. Then, the pediatric electrophysiologist was contacted, and new EKGs were obtained that were significant for bigeminy with a heart rate of 116. It appeared to be polymorphic bigeminy with frequent PVCs.

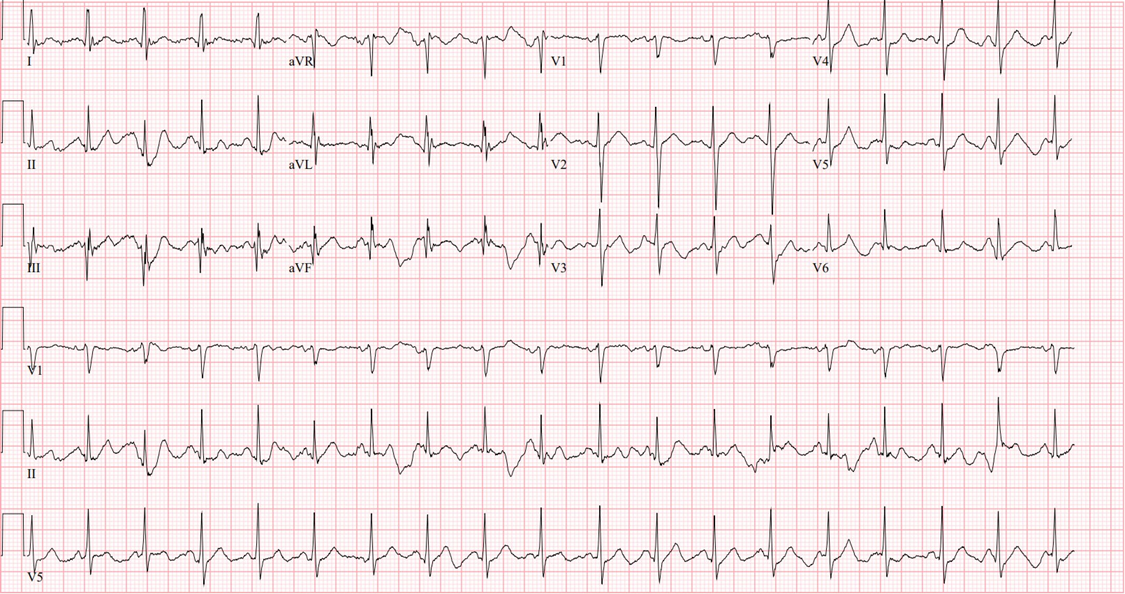

Recommendations by the pediatric electrophysiologist at that time were to increase sedation with a Midazolam bolus as well as starting a Dexmedetomidine drip. The cardiologist was concerned for CPVT and instructed the use of Esmolol drip for transportation. Patient was given two milligrams of lorazepam, then five milligrams of midazolam for sedation as well as fentanyl for analgesia. Repeat EKG after sedation administration showed sinus tachycardia at a heart rate of 111, with resolution of all bigeminy or PVCs. He was then transferred in stable condition on a Dexmedetomidine, Fentanyl, and Esmolol infusion to a tertiary pediatric center.

Discussion

This case report discusses the diagnosis and management of an extremely rare genetic abnormality. The estimated prevalence of CPVT is 1:10,000 [1]. There was high suspicion for this condition due to multiple factors, the patient initially presented in sinus tachycardia and after administering sedation and paralytics for securing the airway he continued to be hemodynamically stable. As the effects of sedation began to wear off, and delay in a sedation drip to be initiated, the patient started to exhibit agitation and signs of ventilator dyssynchrony. The continuous cardiac monitor subsequently revealed new arrhythmias that had not been observed previously. Correlating these findings with the family’s account of the witnessed cardiac arrest, we consulted a pediatric cardiologist, who raised the possibility of this syndrome.

It is likely that this patient’s ventricular tachycardia was precipitated by a combination of prolonged fasting and significant physical exertion, both of which can alter electrolyte balance, increase catecholamine release, and lower the threshold for arrhythmogenesis. These physiological stressors, when compounded by his underlying genetic predisposition, created a milieu conducive to malignant ventricular arrhythmia and subsequent cardiac arrest. This interplay of metabolic stress and genetic susceptibility underscores the multifactorial nature of arrhythmia triggers in pediatric patients and highlights the importance of recognizing extrinsic precipitants that may unmask latent cardiac channelopathies.

Diagnosis should be suspected in individuals who have had syncope during physical activity, family history of juvenile sudden cardiac death triggered by exercise or acute emotion, and/or exercise-induced bidirectional or polymorphic ventricular arrythmias. The diagnosis is made with genetic testing including pathogenic variants in RYR2 or CASQ2 [3]. CPVT arises from genetic mutations that disrupt proteins involved in intracellular calcium handling, particularly the ryanodine receptor responsible for diastolic calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum. These defects lead to excessive calcium release in response to adrenergic stimulation, resulting in delayed after-depolarizations and a heightened risk of atrial or ventricular arrhythmias, which can occasionally precipitate sudden cardiac death. Arrhythmias are typically triggered by physical or emotional stress. The hallmark ECG finding is bidirectional ventricular tachycardia, characterized by alternating QRS complex polarity, though other forms of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation may also be observed [4]. These genes count for 70% of patients [1]. Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia is most often identified when ventricular arrhythmias are provoked during exercise stress testing, in the setting of normal cardiac structure on imaging and a normal resting electrocardiogram [5].

Treatment is usually classified into two groups which are acute and chronic treatments. In the emergency setting while patients are in VT, treatment focuses on rapid termination of VT with defibrillation or cardioversion. Propranolol, 40mg orally, can be used every six hours for first 48 hours with intravenous supplementation for recurrent ventricular arrythmias. Sedation can also decrease ectopic beats through decreasing cardiac stress, and consultation with Pediatric EP. For long-term preventative treatment nadolol one to two mg/kg is used. High-risk patients, including survivors of cardiac arrest, should be considered for implantable cardioverterdefibrillator (ICD) placement [2]. However, this intervention is not without drawbacks, especially in younger patients, where ICD implantation can impact quality of life due to complications such as inappropriate shocks, electrical storms, and increased risk of infections [1-2]. Some other treatment modalities that have shown to decrease mortality include moderate exercise training, flecainide, and left cardiac sympathetic denervation [4].

Our patient remained in the CICU for 11 days, he was eventually extubated and transferred to the general medical floors and initiated oral Nadolol 20mg every morning and 40mg every night.

Genetic testing for cardiomyopathy revealed a pathogenic variant in the RYR2 gene, strongly suggesting that the underlying cause of his cardiac arrest is autosomal dominant catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT). He was ultimately discharged 12 days later with an oral beta blocker, wearable defibrillator, and an outpatient follow up with physical therapy and pediatric cardiology.

Conclusion

Early recognition of increased ectopy on cardiac monitoring by the Emergency Department team was pivotal in preventing potential deterioration. Rather than proceeding with immediate transfer, the ED team appropriately identified the evolving arrhythmia pattern as a safety concern and opted to temporarily delay transport. This decision prompted urgent consultation with the pediatric intensivist and cardiologist to develop a comprehensive stabilization and transfer plan. Following close observation and multidisciplinary discussion, sedation was optimized and beta-blocker therapy was initiated, resulting in prevention of further clinical decompensation. This case illustrates the critical importance of continuous EKG surveillance, early specialist involvement, and situational awareness in the management of rare pediatric arrhythmias. It further highlights the essential role of the ED team in recognizing high-risk changes, prioritizing patient safety, and coordinating multidisciplinary care beyond the initial resuscitation phase.

References

- UpToDate. Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/catecholaminergic-polymorphicventricular-tachycardia. Updated October 30. 2024. 21, 2025:

- Napolitano, C., Priori, S. G., & Raffaella Bloise. (2016, October 13). Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia: Nih.gov; University of Washington, Seattle.

- Abbas, M., Miles, C., & Behr, E. R. (2022, October 21: Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia. Radcliffe Cardiology; Arrhythmia & Electrophysiology Review.

- Mitchell LB, Howlett JG: Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Merck Manual Professional Edition. Merck & Co., Inc.; reviewed/revised June. 20242024, 29:2025.

- Aggarwal A, Stolear A, Alam MM, Vardhan S, Dulgher M, Jang S-J, Zarich SW: Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia: clinical characteristics, diagnostic evaluation and therapeutic strategies. J Clin Med. 2024, 13:1781. 10.3390/jcm13061781

Appendix

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.