Neglected and Underutilized Plant Species (NUS): Promising for Livelihood Option in the Dry Lands of Africa

Anteneh Belayneh Desta*

Department of Biology, College of Natural and Computational Science, Haramaya University, Haramaya, Ethiopia

*Corresponding author:Anteneh Belayneh Desta. Department of Biology, College of Natural and Computational Science, Haramaya University, Haramaya, Ethiopia Tel: +251 0911759139; E-mail:anthil2005@gmail.com

Received Date: 29 March, 2017; Accepted Date: 04 April, 2017; Published Date: 12 April, 2017

Citation: Desta AB (2017) Neglected and Underutilized Plant Species (NUS): Promising for Livelihood Option In the Dry Lands of Africa. Asian J Life Sci 1: 103. DOI: 10.29011/2577-0241.000003

1. AbstractHumankind depends on narrow range of crop diversity to meet its food and other needs, and globally, it became an important scenario to widen this narrow food base in order to serve the growing population. In this context, neglected and underutilized species (NUS) offer an opportunity and potential to provide further sources of food and other needs (like cosmetic, insecticide, repellent, etc.) for livelihood support. The dry lands of Africa harbour rich diversity of NUS, which are grown and maintained by native farmers and others still exist as wild species. Therefore, to maximize these potential dry land biodiversity resources, the documentation of information on the genetic resources/diversity, distribution, and limitations on their use are important. This review work provides an updated account of the plant genetic resources of NUS in the African dry lands. A total of 41 wild and cultivated NUS, which belongs to 37 genera and 23 families were summarized. They are categorized under cereals/pseudo-cereals, pulses, roots/tubers, vegetables, fruits, oil crops, spices and condiments. In addition, the most valuable and promising agro-forestry woody species and multi-purpose NUS, which are well adapted to the dry land environments, were included. The potential of NUS to reduce food and nutrition insecurity, their adaptability to water stress and increased temperature make them essential for sustainable agro-biodiversity in African dry lands. Therefore, in this climate change scenario, the most valuable and promising NUS could be a potential resources for current and future needs to improve the genetic pool of food crops, screening useful wild species for direct use for food and commercial purposes in African dry lands.

2. Keywords: Agro-biodiversity; climate change; genetic resources; food security;wild edible.

1. Introduction

It is estimated that globally two billion people reside in the dry lands and 90% of these vibrant population live in developing countries. Many of whom depend on the biodiversity for their livelihoods. Dry lands cover 41.3% of the earth’s land surface, including 43% of Africa, 40% of Asia, 24% of Europe, and 15% of Latin America [1].This indicates significant portion of the African land mass is dry land.The dry lands of Africa are characterized by low and erratic rainfall (300–600 mm per annum). However, very rich in biodiversity and its products like, natural gums and incense, wild honey, shea butter, edible and medicinal oil extracts from diverse wild nuts, bamboos, essential oil of aromatic plants, spices and condiments, wild fruits, aloe products, perfumes, medicines, etc. [2,3].Yet despite their relative levels of aridity, dry lands contain a great variety of biodiversityincluding important areas of extraordinary endemism [4].

In the world dry lands is the origin of many important food crops like, maize, millet, sorghum,wheat, etc. [5]. At least 30% of the world’s cultivated plants and many livestock breeds originate in dry lands, providing an important genetic reservoir that is becoming increasingly valuable for climate change adaptation [1]. However, this day the dry land biodiversity are under severe threat due to natural and anthropogenic factors. The major threat to dry land biodiversity appears to be the degradation of ecosystems, loss of habitats and land use

changes. There are various drivers of environmental degradation like, urbanization, sedentarization, commercial ranching and monocultures, industrialization, mining operations, wide-scale irrigation of agricultural land, poverty-induced over-exploitation of natural resources [6]. These new forms of disturbances often overpower the legendary resilience of dry land ecosystems and constitute potentially serious threats to dry land biodiversity. Already, as sources quoted by SBSTTA (1999) report, it is estimated that 60 percent of dry lands is already degraded resulting in an estimated annual economic loss of USD 42 billion worldwide. Thus, continued degradation of dry lands is a major threat to the ecological functions, the species and their gene pools and to human welfare. Therefore, the conservation, restoration, and sustainable use of biodiversity in dry lands are central to improving livelihoods and human well-being, poverty alleviation, and sustainable development.

The threats are more severe in African dry lands. The dry lands of Africa are an area of particular concern due to high levels of undernourishment, poverty, and population growth [7]. In addition, land and water degradation, overgrazing, and slash and burn agricultural production practices have led to significant environmental degradation and food shortages exacerbated by climate change [8]. The combination of high exposure to climate variability and low adaptive capacity to climate change makes Africa’s dry land ecosystems vulnerable to loss of ecosystem functions and services such as soil fertility, biomass production, water resources, etc [9]. In this respect, Africa should be the major concern with respect to dry land systems and dealing with the biodiversity potential focusing on neglected and underutilized plant species (NUS) could be reasonably worthy.In most of sub-Saharan Africa, the vast majority of farmers and pastoralists depend on these plant species during the drought seasons. The rich biodiversity of African dry lands are promising for food security and climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies if proper research works and development works are in place.

In this respect biodiversity development should be central even to improve the water and the soil of this fragile ecosystem. Therefore, future food security depends upon developing improved dry land cropping systems through all available biodiversity including the domestication of useful local wild plant species, which are neglected and underutilized. An important component towards tapping the potential of these biodiversity in African dry lands will be to give better attention to the NUS of this ecosystem [10]. The challenge is the least concern from policy and strategy on the development and conservation of these neglected and underutilized plant species [11].

This paper presents a review of the limited research works focused on the diversity, distribution, and challenges of neglected and underutilized plant species in the dry lands of Africa and explores options for its conservation, development, and sustainable use.

1.1 What are neglected and underutilized plant species?

Worldwide, over 7,000 plant species have been grown or collected for food. However, less than 150 have been commercialized and just three crops, i.e. maize, wheat, and rice supply half of the daily proteins and calories [10]. The greater proportion of food plants around the world are little used, or which were grown traditionally but have fallen into disuse, are being revived, especially for use by the poor [12]. The impact of narrowing species base of global food security is likely to be felt most by the rural poor, particularly in marginal areas like dry lands where people are faced with a restricted set of livelihood options.

The terms neglected and underutilized species referring to animals, wild or semi-wild plants and cultivated crop plants applies to those species which appear to have considerable potential for use yet whose potential is scarcely exploited, if not totally neglected, in agricultural production [13]. There are different terms often used in literature as synonyms for underutilized and neglected species like, orphan, abandoned, crops for the future, lost, underused, local, minor, traditional, forgotten, alternative, niche, promising, and underdeveloped. These terms all focus on certain aspects, which restrict a wider use, for example the fact that they have been 'neglected' by scientific institutions or that they are of 'minor' economic importance [14].

Neglected and underutilized crops are those grown primarily in their centres of origin or centres of diversity by traditional farmers, where they are still important for the subsistence of local communities [12,15]. Some species may be globally distributed, but tend to occupy special niches in the local ecology and in production and consumption systems. While these crops continue to be maintained by cultural preferences and traditional practices, they remain inadequately characterized and neglected by research and conservation [13]. The reasons for the underutilization of such species vary: it may be that their useful traits are not well known; perhaps there is little processing or marketing capacity, or a lack of interest on the part of agricultural research.

The use of the two terms, neglected and underutilized, has the advantage of pinpointing two crucial aspects of these species. They highlight the degree of attention paid by users and the level of research and conservation efforts spent on them. Lack of attention has meant that their potential value to human well-being is under-estimated and under-exploited. It also places them in danger of continued genetic erosion and disappearance [16]. Hundreds of these species are still found in many countries, representing an enormous wealth of agro-biodiversity that has the potential to contribute to improved incomes, food security, and nutrition. However, these locally important species are frequently neglected by research and dryland development [17]. This neglect can also lead to the genetic erosion of their diversity and usefulness, further restricting development options for the rural poor [14].

Many neglected and underutilized species occupy important niches, adapted to the risky and fragile conditions of rural communities. They have a comparative advantage in marginal lands where they have been selected to

With stand stress and contribute to sustainable production with minimal inputs [3]. They also contribute to the diversity and the stability of agro-ecosystems [2]. These species also often have a strategic role in fragile ecosystems, such as those found in arid and semi-arid lands, and tropical forests. To address the needs of these resources we must broaden the focus of research and development so that it includes a much wider range of crop species, with the ultimate objective of increasing their sustainable productivity.

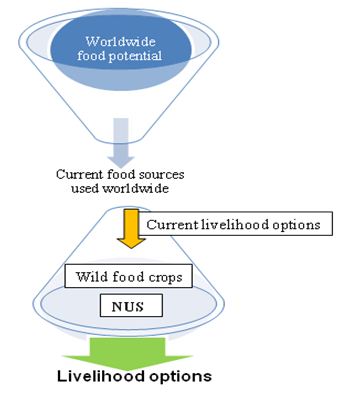

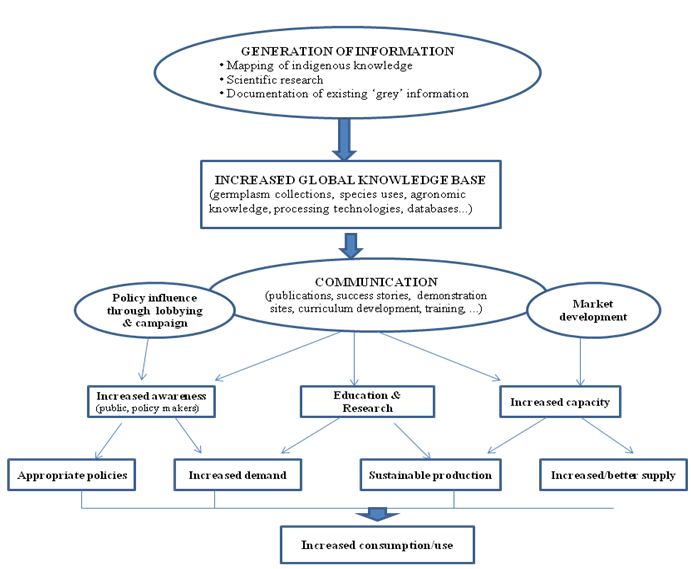

Many of the species that research and development have ignored are rich in cultural, nutritional, and ecological values. Local communities consider them essential elements not only in their diet but also in their food culture and rituals. The link between cultural values and plant resources can be important in empowering communities to conserve and develop their biological and cultural assets [4]. Therefore, increasing research and development could increase the value of 'neglected' and 'underutilized' plant species and make them more widely available, broaden the agricultural resource base, and increase the livelihood options for rural communities, including income generation, food security, and diet diversity [18]. In this respect, the conceptual model has been developed indicating the potential of NUS to widen the livelihood option in the drylands (Figure 1).

1.2 What NUS can offer to African dry lands?

Studies in arid, semi-arid, and temperate areas showed that hunting and gathering remains an important component of the livelihood of pastoral and agro-pastoral communities. The livelihood strategies in all social, economic and ecological setting encompass a wide range of activities in the dry lands. These ranges of activities include the exploitation of the 'hidden harvest' of wild edible plants, while they are neglected and underutilized under research and development [12]. These neglected and underutilized wild edible plants were collected for their fruits, leaves, seeds, nuts, tubers/roots, and flowers. They are used by poor inhabitants and children. They

are known to improve diets by filling the nutritional gap since most of them are rich in vitamins, minerals, proteins, fats, and carbohydrates [15]. Wild fruits provide vitamins and minerals especially to women and children. They provide a number of important dietary elements that the normal agricultural products does not adequately address [19]. For example, Schinziophyton rautanenii has high vitamin E content, around 560 mg per 100 grams of kernel; 60–65% of the kernel of Trichilia emetica is fat; and Ximenia caffrafruit provides 366 µg/g of iron. Though Fonio (Digitaria exilis) is neglected in research and development, it is important locally because it is both nutritious and one of the world's fastest-growing cereals, reaching maturity in as little as six to eight weeks. It is a crop that can be relied on in semi-arid areas with poor soils, where rainfall is unreliable [20].

They also offering fibre, fodder, medicinal and income generation options. They are also closely tied to cultural traditions, and therefore have an important role in supporting social diversity. Neglected and underutilized crops (NUS) are known to be more resilient and better adapted than staple crops to grow in marginal environments constrained by water scarcity, poor soils, and other such yield-limiting factors.Therefore, their development can contribute to climate change mitigation and adaptation [11].

They are also known as famine food since available and used during the drought seasons. Some are used to supplement income since sold in the local markets. In addition, they provide genetic materials for experimentation, medicines, fuel, utensils as well as craft and building materials. They are also often of significant cultural and spiritual importance. Hence, collecting, using, documenting, managing, conserving, experimenting, cultivating and domestication of the NUS should be an issue of the time with in this climate change scenario, especially in the dry lands.

NUS can offer a wide range of economic, social, and environmental values in the dry lands. some of the common reported values are fighting hunger and malnutrition, healthy nutrition and medicinal use, income generation, poverty reduction, sustainable use of natural resources, indigenous knowledge and cultural identity, ecological protection, and climate change mitigation [21,13,11,22].

1.3 For food security: Local crops and animal breeds can increase food security, particularly if they are adapted to specific marginal agricultural conditions. Diversification is a means of risk reduction.

1.4 Healthy nutrition: Many neglected and underutilized crops have important nutritional qualities, such as high fat content, high quality proteins (essential amino acids), a high level of minerals (such as iron), vitamins, or other valuable nutrients, which have not yet been described satisfactorily. They are therefore a significant complement to the 'major' cereals and serve to prevent or combat the hidden hunger - a diet deficient in vitamins, minerals and trace elements - which is prevalent in developing countries.

1.5 Income generation: NUS are capable of supplying both foodstuffs and industrial raw materials, which will offer new opportunities for income generation if their market potential is successfully recognized and developed [13].

1.6 Poverty reduction: Many neglected and underutilized plant species and breeds require few external inputs for production since most of them are naturalized and indigenous to their ecology. This is an incalculable advantage, especially for poor sections of the population. For example, local cattle breeds can thrive without fodder supplements and preventative veterinary treatments. While they may be less productive, their performance remains consistent when conditions are less than ideal. Local crops produce lower but stable yields even on marginal land and without additional inputs of mineral fertilizers and pesticides. If the land in question does not belong to the farmers, it may still be possible to use wild or semi-cultivated species (such as medicinal herbs, dyes, etc.) [13].

1.7 Sustainable use of natural resources: Locally adapted crops and animal breeds offer potential for the sustainable use of more challenging sites, such as arid and semi-arid regions. A well-known example is that local cattle breeds are often less destructive to the vegetation cover on slope land than (heavier) high performance breeds. Local crop species and varieties fit easily into traditional sustainable farming systems geared towards maintaining or restoring soil fertility, like mixed cropping and agro-forestry. The local breeds and crops can be used as an alternative genetic resource for dry land livelihood improvement [21].

1.8 Indigenous knowledge and cultural identity: Many smallholders possess very specific knowledge of cultivation and processing techniques for underutilized species and their diverse uses. It is not unusual for certain plant or animal species to be of great spiritual importance for the people and their cultural identity.

2. The potential of NUS in the African dry lands

2.1 Diversity and distribution of NUS

Agricultural production is dominated by a narrow range of crop species. This fact threatens the resilience and stability of food security in the face of global climate change. Diversification through increased cultivation of neglected and underutilized species (NUS) has the potential to enhance the resilience and adaptability of agricultural systems. NUS are often resistant to marginal and stressful conditions such as drought, cold and water logging. Despite their great potential, very little is known about how farmers worldwide are using these species to cope with climate change.

In this review a total of 41 species that belongs to 23 Families and 37 genera were covered (Table 1). Among these plant species the largest proportion are woody species of 20 trees, 4 shrubs, and 4 shrub/tree. The rest 10 plant species are annual herbs, 2 annual creeping, and 1 grass. Most of these plant species are locally used for their edible fruits and seed/kernel used to extract edible and industrial oils. About 17 plant species were reported as their fresh fruits are eaten raw as well as used to prepare sweet juices. Other 15 plant species seeds/nuts/kernel are used to extract oils which are used for various purposes like edible, cosmetics, medicinal, and industrial uses. In addition, few species are used for their leaves as vegetable, tuber served after cooked, and gums used to manufacture candy and additives in chemical products.

2.2 The most valuable and promising NUS in the dry lands

A total of 14 most valuable and promising dry land woody species from the social, economic, and environmental perspectives in the changing climate, despite the fact that neglected and underutilized so far, are discussed below.

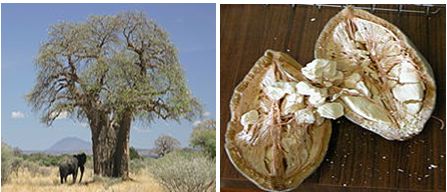

2.2.1 Adansonia digitata

Adansonia digitata (Malvaceae) is the most widespread of the Adansonia species in the dry lands of Africa, commonly found in the dry savannahs of sub-Saharan Africa. Its popular common name is baobab. Some other common names for the baobab include dead-rat tree, monkey-bread tree, and cream of tartar tree. In the scientific name of the Baobab, Adansonia digitata, the genus name "Adansonia" came from the French explorer and botanist, Michel Adanson (1727-1806). The specific epithet "digitata" refers to the digits of the hand since the baobab's branches and leaves are akin to a hand.

The Baobab is native to most of Africa, especially in drier, less tropical climates where sand is deep in Acacia-Balanites-Adansonia woodland and wooded grasslands. It is a deciduous tree, meaning they lose their leaves in the dry season and stay leafless for nine months of the year. This allows the tree to survive well in a dry climate. The plant height ranges from 5 to 25 meters with a diameter range of 10 to14 m (Figure 2).

The vitamin-rich fruits of baobab tree are eaten as fresh as well as dissolved in milk or water to make a drink. The leaves can be eaten as relish. Young fresh leaves are cooked in a sauce and sometimes are dried and powdered. The powder is sold in many village markets in Western Africa. Oil extracted by pounding the seeds can be used for cooking but this is not widespread. In Sudan, where the tree is called tebeldi, people make tabaldi juice by soaking and dissolving the dry pulp of the fruit, locally known as gunguleiz [23]. The leaves has been suggested to have the potential to improve nutrition, boost food security, foster rural development, and support sustainable land care [24]. The European Union (In 2008) and the United States Food

and Drug Administration (in 2009) granted generally recognized as safe status to baobab dried fruit pulp as a food ingredient [25]. Cattle, sheep, goats, and wild animals eat the leaves, shoots, and fruits of baobab tree.

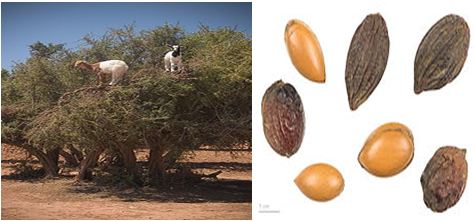

2.2.2 Argania spinosa

Argania spinosa(Sapotaceae) is a tree endemic to the calcareous semi-desert Sous valley of south-western Morocco and to the Algerian region of Tindouf in the western Mediterranean region of African woodlands. Its common name is Argan. The plant height ranges from 8-10 meters and live up to 150-200 years (Figure 3). The

fruit is source of Argan oil rich seeds. The traditional technique for oil extraction is to grind the roasted seeds to paste, with a little water, in a stone rotary quern. The paste is then squeezed by hand in order to extract edible oil. The extracted paste is still oil-rich and is used as animal feed.

Argan oil is sold as a luxury item. The product is of increasing interest to cosmetics companies in Europe. The oil is traditionally used as a treatment for skin diseases and as cosmetic oil for skin and hair, so that European cosmetics manufacturers have favour it [26]. The Argan tree provides food, shelter and protection from desertification. The tree's deep roots help prevent desert encroachment. The canopy of the argan tree also provides shade for other agricultural products, and its leaves and fruit provide food for animals [27].

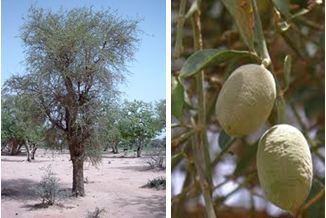

2.2.3 Balanites aegyptiaca

Balanites aegyptiaca (Balanitaceae) is a tree native to much of the Sahel-Savannah region across Africa and parts of the Middle East. Its popular common name is desert date. Some other English names for the plant include soapberry tree, thorn tree, Egyptian myrobalan, Egyptian balsam and Zachum oil tree. The plant is tolerating a wide variety of soil types, from sand to heavy clay, and climatic moisture levels, from arid to sub-

humid. It is relatively tolerant of flooding, livestock activity, and wildfire. [28]. This spiny tree reaches 10 m in height (Figure 4). It is found wild except cultivated in Egypt. Its natural habitat is in dry savannah or Acacia woodland, rarely in Terminalia-Combretum wooded grassland, on a variety of soils; open scrub community, in sandy or stony soils, usually near dry streambeds

Many parts of the plant are used as famine foods in Africa like, the leaves are eaten raw or cooked, the oily seed is boiled to make it less bitter and eaten mixed with sorghum, and fruit and flower are edible. The tree is considered valuable in arid regions because it produces fruit even in dry times. The fruit can be fermented for alcoholic beverages. Juice is made out of the fruit and oil is extracted from the seed. The seed cake remaining after the oil extraction commonly used as animal fodder. The tree is managed through dry land agro-forestry since known to fix nitrogen [28]. In Somalia, the fruits are sometimes sold in local markets as 'desert dates', eaten like candy (dried or fresh) and used to produce 'balanos oil'. Livestock feed on fruits, leaves and green thorns.

2.2.4 Berchemia discolor

Berchemia discolor (Rhamnaceae) a semi-deciduous shrub or tree with a dense, rounded crown. ‘Berchemia’ is named after M. Berchem, a French botanist, and ‘discolor’ means with 2 or more colours, referring to the fact that the upper and the lower surfaces are different colours. ‘Dis’ is a Latin prefix meaning ‘2’. It can grow up to 8 metres tall (Figure 5). A multipurpose tree providing food, medicines and various commodities for local use. In particular, the fruit is commonly collected from the wild, often being dried and stored for later use, whilst the wood is one of the hardest in eastern Africa. The fruit is also sold in local markets.

Bird plum is a fruit from Africa and wide spread from the Sudan to South Africa and growing in dry open woodland, semi-arid bush land and along riverbanks in Angola, Botswana, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Madagascar, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Somalia, South Africa, Swaziland, Tanzania, Uganda, Yemen, Republic of, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Its habitat is Acacia-Commiphora-Balanites woodland and wooded grassland, and Acacia bush land on alluvial soil. The date-like yellow fruit, which has seeds embedded is sweaty flesh, is eaten raw and used to make juice. It can be boiled and eaten with sorghum. A fruit is pleasant, sweet-tasting flesh. The gum is also edible. When it is soaked in water over-night, the solution is very much liked by people

2.2.5 Cordeauxia edulis

Cordeauxia edulis (Fabaceae/Caesalpinioideae) is a small evergreen multi-stemmed tree or shrub species endemic to Ethiopia and Somalia and the sole species in the genus Cordeauxia. Commonly called yeheb. It is one of the economically most important wild plant at the Horn of africa, but it is little known outside of its distribution area. It is dominant or co-dominant in the deciduous Acacia-Commiphora bush land vegetation of the Somali-Masai floristic zone [29]. It is drought hardy and a source of food for both animals and humans. Commonly it grows up to about 1.6 m height but it also can grow up to 4 m (Figure 6). The Yeheb tree has a taproot system, which can go 3 m deep so that it reaches deep water and can stay green all the year round.

The tree produces nuts that are collected and consumed as a staple food by pastoralists and sold in local markets to provide household income. Because of high demand and competition, the fruits of C. edulis are usually collected prematurely. Recent reports indicate that C. edulis has vanished from many locations where it was noted by earlier travellers and, as a result, it is currently categorized as vulnerable on the IUCN Red List. Yeheb foliage is a preferred browse for camels and goats, which are the dominant livestock in the region, and is heavily browsed throughout the year. The wood of yeheb is also a preferred building material because it is termite resistant [30].

2.2.6 Schinziophyton rautanenii

Schinziophyton rautanenii(Euphorbiaceae) is a deciduous large, spreading tree found on wooded hills and amongst sand dunes, and is associated with the Kalahari sand soil-types in Southern African dry lands, which reaches from northern Namibia into northern Botswana, south-western Zambia and western Zimbabwe. Another belt is found in eastern Malawi, and yet another in eastern Mozambique (Wikipedia). Its common names are mongongo fruit, mongongo nut, and manketti nut. The plant height ranges from 15 to 20 meters (Figure 7).

Its fruit contain a thin layer of edible flesh around a thick, hard, and pitted shell. Inside this shell is a highly nutritious nut and eaten fresh, which is popular traditional food. The popularity stems in part from its flavour, and in part from the fact that can be stored well, and remain edible for much of the year. Extracted oil from the kernels is traditionally used as a body rub in the dry winter months to clean and moisten the skin [31]. Some bush men also dry the pulp and keep it for later use even after months.

2.2.7 Sclerocarya birrea

Sclerocarya birrea(Anacardiaceae) is a tree, indigenous to the miombo woodlands of Southern Africa, the Sudano-Sahelian range of West Africa, and Madagascar. The tree grows up to 18 m tall mostly in low altitudes

and open woodlands (Figure 8). It is commonly known as marula. Some other English names include, jelly plum, cat thorn, and cider tree.

The fruit of the marula tree is collected from the wild and traditionally used for food in Africa, and has considerable socio-economic importance. Marula fruit is used to make Amarula liqueur. The fruit is delivered to processing plants where fruit pulp, pips, kernels and kernel oil are extracted and stored for processing throughout the year, which is used as an ingredient in cosmetics [32].

2.2.8 Strychnos cocculoides

Strychnos cocculoides(Strychnaceae) is an evergreen tree found in the drier parts of tropical and southern Africa. Common name is corky-barked monkey-orange. It grows up to about 8 m tall (Figure 9). The tree is usually found in open woodland on flat, sandy soil or rocky slopes in South Africa; Botswana, Zimbabwe, Zambia, northern Namibia, Angola and eastwards to Tanzania, Mozambique and southernmost Kenya [9].

This tree grows in woodlands that are burnt essentially annually, and so the most obvious ecological adaptation concerns a strategy for surviving fire. Woody plants growing in these conditions have developed two main strategies for survival: either keep reserves safely underground and sprout new aerial growth after every fire, or protect the main trunk and as many branches as possible from the heat as the fire passes through (that is why known as corky-barked). The fruits are eaten fresh in the area where this tree grows naturally.

2.2.9 Tamarindus indica

Tamarindus indica(Fabaceae) is an evergreen tree indigenous to tropical Africa. It is commonly known as tamarind. It grows in wild and as well as cultivated. Because of the tamarind's many uses, cultivation has spread around the world in tropical and subtropical zones. It grows 12 to 18 metres height (Figure 10).

The tamarind tree produces edible, pod-like fleshy fruit, which is used extensively in cuisines around the world. The ripened palatable fruit becomes sweeter and less sour (acidic) as it matures. It is used in desserts as a jam, blended into juices or sweetened drinks, sorbets, ice creams, and other snacks [32] Other uses include traditional medicine and metal polish.

2.2.10 Trichilia emetica

Trichilia emetica (Meliaceae) is an evergreen with wide spreading crown tree widely distributed in tropical Africa and occurs from east of Senegal to Eritrea and South Africa. It is commonly known as Mafura butter. Some other English names include natal mahogany, Ethiopian mahogany, and Christmas bells. Trichilia emetica is Red Listed as Least Concern (LC) [33]. It grows up to 25 m tall in various types of woodlands (Figure 11) with separate male and female plants. Its sweet-scented flowers can attract bees and birds to the garden while found in cultivation.

The seed of Trichilia emetica yields two kinds of oil: ‘mafura oil’ from the fleshy seed envelope (sarcotesta) and ‘mafura butter’, also called ‘mafura tallow’, from the kernel. Mafura oil is edible, but mafura butter is unsuitable for consumption because of its bitter taste. It is used in soap and candle making, as a body ointment, wood-oil and for medicinal purposes.

2.2.11 Uapaca kirkiana

Uapaca kirkiana (Phyllanthaceae) is one of the most popular wild fruit tree in the zone where eastern Africa meets southern Africa. The species has been recorded growing in Angola, Burundi, Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania, Zaire, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. It is commonly known as sugarplum. It is a miombo woodland species. It is rarely cultivated but fruiting trees are left when land is being cleared. The tree is dioeciously and grows to a height of 5–13 meters, and 15–25 cm in trunk diameter (Figure 12).

It is a traditional food plant in Africa, which is little-known fruit though has the potential to improve nutrition, boost food security, foster rural development and support sustainable land care [34].

2.2.12 Vitellaria paradoxa

Vitellaria paradoxa(Sapotaceae) is a tree indigenous to Africa. It is commonly known as shea tree. The shea tree grows naturally in the wild and native in the dry savannah belt of West Africa from Senegal in the west to Sudan in the east. It occurs in 19 countries across the African continent [24]. It grows up to 20 m tall and 1 m in diameter, with a dense, many-branched crown (Figure 13). Though found in the wild there are few domestication and plantation trials in the Sahel [35].

The shea fruit consists of a thin, tart, nutritious pulp that surrounds a relatively large, oil-rich seed from which shea butter is extracted. It is a key species in traditional agro-forestry systems (vital for erosion control) in the dry lands and an important source of edible oil, shea butter, which is derived from the seed. Shea butter is also used in cosmetics, skin emollients, and pharmaceuticals. The shea tree is a traditional African food plant. It has been claimed to have potential to improve nutrition, boost food supply in the "annual hungry season", foster rural development, and support sustainable land care [36]. Shea can also be used for its edible flowers and fruit. It is classified as vulnerable on the IUCN red list.

2.2.13 Ximenia caffra

Ximenia caffra (Olacaceae), is a small tree or small shrub native throughout tropical regions. In particular, the sourplum is native to regions in South East Africa, mainly Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. It is commonly known as large sour plum. The sour plum tree is a sparsely branched shrub or small tree around 2 m in height with a shapeless untidy crown. Sometimes, it has been known to grow about 6 m in height (Figure 14). The tree itself is hardy, with frost resistance and drought tolerance. In the wild, it is found in woodlands, grasslands, rocky outcrops and sometimes termite mounds.

The fruit, seed, leaves, and roots are all used for human consumption, and medicinal. The fruit is sour but can be eaten raw; it is best eaten when slightly overripe. More typically, it is immersed into cold water to soak, and then the skin and seed are easily removed by pressing. The remaining pulp is then mixed with pounded tubers to prepare porridge. Alternatively, the fruits can also be processed into a storable jam. The fruits are also known to be used for desserts and jellies [37]. Birds and various other animals eat the fruits. Several butterfly species are known to feed on the leaves. Various mammals are known to graze on the leaves of the tree, with particular emphasis in times of drought.

2.2.14 Ziziphus spina-christi

Ziziphus spina-christi (Rhamnaceae) is a tropical fruit tree species. Commonly known as ber. Some other common names include Chinese apple, jujube, and Indian plum. It is a spiny, evergreen shrub or small tree widely naturalised throughout the old world tropics from Southern Africa through the middle east to the India sub-continent and China, Indo-Malaya, and into Australia and the pacific Islands. The species varies widely in height, from a bushy shrub 1.5 to 2 m tall, to a tree 10 to 12 m tall with a trunk diameter of about 30 cm or more; spreading crown (Figure 15).

Z. spina-christi is hardy tree that copes with extreme temperatures and thrives under rather dry conditions. The fruit is eaten raw, pickled or used in beverages. It is quite nutritious and rich in vitamin C [38].

3. Threats on the NUS

In many dry land areas wild and cultivated NUS are declining and some are at risk of extinction. Research out puts indicated that levels of protection in their centres of origin and diversity are considerably lower than the global average [4]. Some NUS have been so neglected that genetic erosion of their gene pools has become so severe that they are often regarded as lost crops [39]. Although neglected and underutilized plant species have great potential for helping to address important concerns in the dry land areas, the full development of their

potential was hampered by lack of awareness in the society, as well as due to lack of relevant capacity within the research community [40]. At the same time, global and local pressures increasingly threaten these plant resources and the land they are grown on [11].Yet while many NUS have nutraceutical properties, their natural resource base is often threatened by unsustainable harvesting techniques that are prompted by population pressure, land conversion or other factors [35].

Although NUS as a food cannot substitute for cereal grains, most of them could supply vitamins or other substances of dietary significance and are used to supplement the daily diet, generate income, and substitute occasionally for meals. However, this fallback may be threatened by land-use change if the common woodland, grassland or agricultural fallows on which many wild foods are reduced [4]. In addition, so far received little attention from research, extension services, farmers, policy and decision makers, donors, technology providers, and consumers [17]. The development of NUS is still hampered by a general lack of awareness in all sectors of society and a lack of the necessary capacity within the research community. Therefore, indigenous knowledge also needs to be mapped before it is lost, and research into active compounds and sustainable harvesting methods is necessary.

4. Strategies and way forward for NUS development

One of the best-recognized strategies of intervention for the development of NUS focused on the generation of new knowledge base through mapping of indigenous knowledge and further scientific research to increase the global knowledge/information on the NUS.Better communication of this new knowledge/information in order to raise awareness and build capacity amongst stakeholders and ultimately increase demand for NUS and their products through demonstration sites, collection of success stories, targeted campaigns, development of school curricula and training. Ultimately these intervention results could influence policy at all levels to remove barriers to production and marketing [13,11,35]. If this strategies could be well planned could results in appropriate policy for the development of NUS, which could followed with sustainable production, increased demand, better supply and finally reach on increased consumption or use of the NUS (Figure 2).

This flowchart diagram was developed based on the descriptions of various literatures indicated the best practices and designed strategies for potential development of the NUS in the dry lands of sub-Saharan Africa and Asia [13,11,35]. This piece of work is part of these strategies for generation of information to increase knowledge on the NUS that could lead to policy influence, research, and education purpose. In addition, due to the complexities involved in developing the potential of neglected and underutilized plant species, clear concepts for action need to be formulated and made widely known, and consortia of complementary partners need to be formed [11]. The roles of the diverse partners should be clarified and coordinated. Such partners include international and national agricultural and horticultural research organizations, advanced research institutions, non-governmental organizations, community based organizations, private companies, national governments, regional and international organizations, and donors and funding agencies [13].

5. Conclusion

The world is presently over-dependent on small number of plant species. While about 7,000 plant species have a potential source for food, the world depends on less than 150 plant species now. Over-dependence on only these much number plant species exacerbated many acute difficulties faced by communities in the areas of food security, nutrition, health, ecosystem sustainability, and cultural identity. An increasing population pressure made the situation more severe. Therefore, diversification of production and consumption habit to include a broader range of plant species, in particular those currently identified as 'neglected' and 'underutilized', can contribute significantly to improved health and nutrition, livelihoods, household food security, and ecological sustainability.

In African dry lands NUS have great potential of contribution to improve income, food security and nutrition, and for combating the 'hidden hunger' caused by micronutrient (vitamin and mineral) deficiencies, have medicinal properties, and other multiple uses. NUS are strongly linked to the cultural heritage of their places of

origin, tend to be adapted to specific agro-ecological niches and marginal land with traditional uses in localized areas. In addition, they have weak or no formal seed supply systems, which are collected more of from the wild or produced in traditional production systems with little or no external inputs. Relatively they received little attention from research, extension services, farmers, policy and decision makers, donors, technology providers and consumers whose distribution, biology, cultivation and uses are poorly documented. That is why, within this climate change scenario, which had been exacerbated the drought situation in the dry lands of Africa, the value of NUS should be part of the strategic options.

Though policy makers and researchers recognizing the value of NUS and their indigenous ecology, the current capacity to conserve them and improve their yield and quality is limited. One major factor hampering efforts towards the development of NUS is that information on germ plasm is not readily accessible. Often such information is found in ‘grey literature’ and/or is documented in languages, which may not be familiar to researchers. Moreover, knowledge about the potential value of NUS is limited. All of these factors represent obstacles to the successful promotion and conservation of NUS. Therefore, the dry land development policy needs to consider the value of NUS as a strategy for product diversification, adaptation mechanism, and dry land agro-forestry option. NUS development could be a strategic option for dry land ecosystem improvement in addressing social, economic, and environmental concerns. The distribution, wild population, regeneration status, seed germination, field gene bank establishment, and current threats of NUS in the dry land ecosystem could be research focus to foster proper development strategies in the dry lands of Africa. Because, in this climate change scenario, NUS could be a good candidate and option in an integrated development strategies due to their adaptation potential to the dry land environment.

Figure 1: Conceptual model showing the potential of NUS to widen the livelihood option in the drylands.

Figure 2: The baobab tree and its dry pulp of the fruit.

Figure 3:Argan tree and its fruits and seeds.

Figure 4: Balanites aegyptiaca tree and its fruits.

Figure 5: Berchemia discolortree and its fruits.

Figure 5: Berchemia discolortree and its fruits.

Figure 7: The mongongo tree and its fruits (nuts).

Figure 8: The marula tree and its fruits.

Figure 9: Strychnos cocculoidestree and its fruit.

Figure 10: The tamarind tree and its nuts from fruits/pod.

Figure 11: Trichilia emetica tree with its fruit.

Figure 12: Thesugarplum tree and its fruit.

Figure 13: The shea tree with fruits and its nuts from fruits.

Figure 14: The sourplum tree with fruits.

Figure 15:Ziziphus spina-christitree and its fruits.

Figure 16: Best practice strategies for the development of NUS (ovals indicated potential intervention mechanisms/areas and rectangles indicates potential results of interventions).

|

No.

|

NUS list |

Family |

Common name |

Habit |

Part used |

Uses |

Distribution in Africa |

|

1 |

Acacia karroo Hayne |

Fabaceae |

Sweet Thorn |

Tree |

Gum |

Used for chemical products |

Angola to Mozambique |

|

2 |

Adansonia digitata L. |

Malvaceae |

Baobab |

Tree |

Fruit and leaves |

Edible fruit and cooked vegetable |

Sub-Saharan Africa |

|

3 |

Amorphophallus abyssinicus (A.Rich.) N.E.Br. |

Araceae |

Herb |

Tubers |

Edible cooked |

Tropical Africa, S. of Namibia to N. Sudan |

|

|

4 |

Argania spinosa (L.) Skeels |

Argan |

Tree |

Nut/ kernels |

Its oil is edible and cosmetic for skin and hair |

Northern Africa |

|

|

5 |

Balanites aegyptiaca (L.) Del. |

Balanitaceae |

Desert date |

Tree |

Fruit/seeds |

Edible/oil |

Sahel-Savannah region across Africa and middle east |

|

6 |

Balanites rotundifolia (van Tieghem) Blatter |

Balanitaceae |

Tree |

Fruit |

Eaten fresh and make juice |

Ethiopia, Kenya, Djibouti, Somalia |

|

|

7 |

Berchemia discolor (Klotzsch) Hemsl. |

Rhamnaceae |

Wild almond/ Bird Plum |

Tree |

Fruit |

Eaten raw |

E. and S. Africa, Madagascar |

|

8 |

Carapa procera DC. |

Crab wood |

Tree |

Oil from Nut |

Therapeutic, cosmetic, insecticide and repellent |

Tropical Africa |

|

|

9 |

Cephalocroton cordofanus Hochst. |

Euphorbiaceae |

Shrub |

Seed |

Rich in a highly unsaturated oil used in cooking |

Nigeria, Sudan, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Tanzania |

|

|

10 |

Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Matsum. & Nakai * |

Cucurbitaceae |

Dessert watermelon |

Annual creeping |

Fruit |

Eaten raw, sweet juicy pulp |

W. African semi arid regions |

|

11 |

Cordeauxia edulis Hemsley |

Fabaceae |

Yeheb |

Shrub/ tree |

Nut |

Cereal crop |

Ethiopia and Somalia |

|

12 |

Crambe hispanica L. |

Brassicaceae |

Abyssinian crambe |

Herb |

Seed |

Inedible seed oil for industries |

Tropical and subtropical Africa |

|

13 |

Cucumis melo L. * |

Cucurbitaceae |

Musk-melon |

Annual creeping |

Fruit/Seed |

Consumed fresh for the sweet and juicy pulp, extract oil |

Originated in East Africa, occurs warm and dry areas of Africa |

|

14 |

Dialium guineense Willd. |

Fabaceae |

Velvet tamarind |

Tree |

Fruit |

Edible fruits |

sub-Saharan Africa/ west Africa |

|

15 |

Digitaria exilis (Kippist) Stapf |

Poaceae |

White fonio/ hungry rice |

Herb |

seeds |

Cereal crop used for porridge, couscous, bread, and local beer |

|

|

16 |

Digitaria iburua Stapf. |

Poaceae |

Black fonio |

Herb |

seeds |

Cereal crop used for porridge, couscous, bread, and local beer |

Nigeria, Niger, Togo, and Benin |

|

17 |

Garcinia buchananii Baker |

Clusiaceae |

Granite garcinia |

Tree |

fruit |

Edible raw and Tasty, root is used as aphrodisiac |

Tropical Africa |

|

18 |

Jatropha curcas L. * |

Euphorbiaceae |

Barbados nut, physic nut |

Shrub |

Nut |

Industrial Oil/high-quality bio-fuel or biodiesel |

tropical and subtropical Africa |

|

19 |

Lannea schimperi (Hochst. ex A.Rich.) Engl. |

Anacardiaceae |

Rusty-leaved lannea |

Tree |

fruit |

Edible raw/eaten fresh |

Tropical Africa |

|

20 |

Lippia javanica (Burm.f.) Spreng |

Verbenaceae |

Fever tea/ Lemon Bush |

Shrub |

leaves |

Tea and oil extraction |

tropical Africa |

|

21 |

Ocimum forskolei Benth. |

Lamiaceae |

Herb |

Leaf |

Aromatic/repellent |

Dryland of E. Africa |

|

|

22 |

Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) Miller |

Cactaceae |

Indian fig |

Shrub/ tree |

Fruit |

Edible |

arid and semi-arid parts of Africa |

|

23 |

Pennisetum glaucum (L.) R. Br. * |

Poaceae |

Pearl millet |

Annual grass |

Seed |

Cereal crop |

E. & W. African and Indian drylands |

|

24 |

Pistacia aethiopica Kokwaro |

Anacardiaceae |

Shrub /tree |

Gum |

Economic importance |

Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, Tanzania, Uganda, & Yemen. |

|

|

25 |

Premna oligotricha Baker |

Lamiaceae |

Shrub |

Leaves |

Spice and condiment |

Somalia, Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania |

|

|

26 |

Martyniaceae |

Devil’s Claw |

Annual herb |

Fruit and seed |

Edible |

Zimbabwe |

|

|

27 |

Schinziophyton rautanenii Hutch. ex Radcl.-Sm. |

Euphorbiaceae |

Mongongo |

Tree |

Fruit/nut |

Edible fruits, oil is extracted from the kernels to clean & moisten skin |

|

|

28 |

Sclerocarya birrea (A. Rich.) Hochst. |

Marula |

Tree |

Fruit and kernel |

Edible fruit and marula oil from kernel used as an ingredient in cosmetics |

Sub-Saharan Africa, S. Africa, Sudano-Sahelian range of W. Africa, & Madagascar |

|

|

29 |

Selaginellaceae |

Resurrection plant/dinosaur plant |

Herb |

Vegetative parts and leaves |

Sold as a novelty and used as tea |

Sub-Saharan Africa, |

|

|

30 |

Strychnos cocculoides Baker |

Strychnaceae |

corky-bark monkey-orange |

Tree |

fruit |

Edible/sweet taste |

Tropical africa |

|

31 |

Tamarindus indica L. |

Fabaceae |

Tamarind |

Tree |

Flowers, leaves and pods |

Edible and used in a variety of dishes |

Tropical belt of Africa |

|

32 |

Terminalia brownii Fresen |

Combretaceae |

Red pod terminalia |

Tree |

Stem |

Aromatic, Beatification, medicinal |

N. Nigeria, E. Somalia, SE DR Congo and N. Tanzania |

|

33 |

Terminalia catappa L. |

Tropical almond |

Tree |

Leaves |

tropical regions of Asia, Africa, and Australia |

||

|

34 |

Trichilia emetica Vahl |

Meliaceae |

Christmas bells |

Tree |

Seed and kernel |

Mafura oil edible, and mafura butter used for soap and candle making, body ointment. |

Southern Africa |

|

35 |

Uapaca kirkiana Muell. Arg. |

Sugar plum |

Tree |

Fruit |

edible/sweet taste |

Angola, Burundi, Malawi, Zambia, Tanzania, Zaire, Mozambique, and Zimbabwe |

|

|

36 |

Vernonia galamensis (Cass.) Less. |

Asteraceae |

Ironweed |

Herb |

Seed |

east Africa/ Ethiopia |

|

|

37 |

Vigna subterranea (L.) Verdc. |

Fabaceae |

Bambara groundnut |

Seed |

African dry land |

||

|

38 |

Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp. * |

Fabaceae |

Cowpea |

Annual herb |

Seed and pods |

Multipurpose uses, food and fodder |

semiarid tropics of Asia, Africa, |

|

39 |

Vitellaria paradoxa C.F.Gaertn. |

Shea butter tree |

Tree |

Seed |

Dry savannah Belt of west and east Africa |

||

|

40 |

Ximenia caffra Sond. |

Suurpruim |

Shrub/ tree |

Fruit |

Edible |

South East Africa |

|

|

41 |

Ziziphus spina-christi (L.) Desf. |

Jujube |

Tree |

Fruit |

Eaten raw or used in beverages |

S. Africa to Middle East; |

Table 1: List of neglected and underutilized plant species distributed in African dry lands with their reported popular uses.

6. IUCN. 1999. Biological Diversity of Drylands, Arid, Semiarid, Savanna, Grassland and Mediterranean Ecosystems. IUCN, the World Conservation Union.

7. FAO (2009) Food Security Statistics of the FAOSTAT Database. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

9. Burkill H M. 1995. The useful plants of West tropical Africa. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

13. GTZ (2002) Protection by Utilization - Economic Potential of Neglected Breeds and Crops in Rural Development. GTZ, Eschborn, Germany.

15. Paya KG (2005) Availability of Indigenous food plants: Implication for Nutrition Security. Harry Oppenheimer Okavango Research Centre, University of Botswana, Maun.

16. SBSTTA (1999) Biological diversity of drylands, arid, semi-arid, savannah, grassland and Mediterranean ecosystems. Draft recommendations to COP5. Montreal, Canada 16.

20. National Research Council (1996) "Baobab". Lost Crops of Africa: Volume II: Vegetables. Lost Crops of Africa 2. National Academies Press.

21. Thies E (2000) Promising and Underutilized Species, Crops and Breeds. GTZ, Eschborn, Germany.

30. Yusuf M. 2010.Cordeauxia edulis (yeheb): resource status, utilization and management in Ethiopia. PhD thesis. University of Bangor, Bangor, UK.

34. National Research Council 2008c. Sugarplums. Lost Crops of Africa: Volume III: Fruits. Lost Crops of Africa 3. National Academies Press.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.